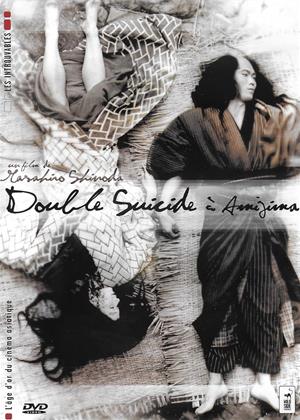

Double Suicide (1969)

- General info

- Available formats

- Synopsis:

- Racking up Best Picture and Best Actress awards in the Japanese equivalent of the Oscars, this acclaimed drama from director Masahiro Shinoda tells the story of a tragic love affair between a married merchant (Kichiemon Nakamura) and a prostitute (Shima Iwashita). Based on an 18th-century Bunraku puppet play, the film follows the increasingly desperate lovers as they enter into a suicide pact when society offers them no hope for happiness.

- Actors:

- Kichiemon Nakamura, Shima Iwashita, Shizue Kawarazaki, Tokie Hidari, Sumiko Hidaka, Yûsuke Takita, Hôsei Komatsu, Takashi Sue, Masashi Makita, Makoto Akatsuka, Unko Uehara, Shinji Tsuchiya, Kaori Tozawa, Yoshi Katô, Kamatari Fujiwara

- Directors:

- Masahiro Shinoda

- Producers:

- Masayuki Nakajima, Masahiro Shinoda

- Writers:

- Monzaemon Chikamatsu, Masahiro Shinoda, Tôru Takemitsu, Taeko Tomioka

- Aka:

- Shinjû: Ten no Amijima

- Genres:

- Classics, Drama, Romance

- Collections:

- People of the Pictures, Remembering - A Special Spring Tribute: Part Two

- Countries:

- Japan

More like Double Suicide

Reviews (1) of Double Suicide

Fate in Black: Theatre, Love, and the Trap of Rules - Double Suicide review by griggs

Double Suicide throws you straight into the mechanics of storytelling. It opens with a Bunraku troupe getting ready, then slips into the “real” drama — except it never lets you forget the stage. The puppeteers, dressed in black, hover at the edges and sometimes step right into scenes, guiding the actors like visible fate. It’s a brilliant trick: you’re watching people behave, while also watching the rules that make them behave.

The story itself is a period morality tale, but the morals are… prickly if you’re coming at it from the outside. A bonded sex worker and a businessman willing to torch his life for her make choices that are both romantic and terrifying, because the rules keep tightening until there’s nowhere left to go. The film asks you to take the code seriously even as it shows how ruinous it is.

What I admired most was the beauty and control: the frames feel carved, the movement feels choreographed, and the whole thing has a ritual rhythm. I didn’t always feel emotionally grabbed, partly because it’s so busy being clever about its own cleverness. That’s on me as much as the film. Double Suicide is still an astonishing piece of theatre on screen.