Fifteen years after he stopped directing feature films, Hungarian maestro Béla Tarr has died at the age of 70. Cinema Paradiso looks back at the work of a unique figure in screen history.

'I hate linear storytelling,' Béla Tarr once said. 'The logic of those films, generally, is action, cut, action, cut. And for me that's ridiculous. I like to listen for the details, the faces and reactions and all small things. For me, a piece of a wall can be a story itself.' It should come as no surprise to learn that Tarr's favourite painting was Pieter Bruegel the Elder's 'Landscape With the Fall of Icarus' (c.1560), as the foreground action showing peasants going about their chores matters far more than the mythical hero falling from grace.

Anyone who has seen the masterworks Tarr produced in his later career will recognise his gruff championing of what became known as 'slow cinema'. But many critics make the mistake of dividing his ouevre into distinctive phases. According to Tarr, however, 'I'm working for 30 years, and I'm doing the same movie. About human dignity. One thing is important: human dignity. Please don't destroy it. Please don't humiliate.'

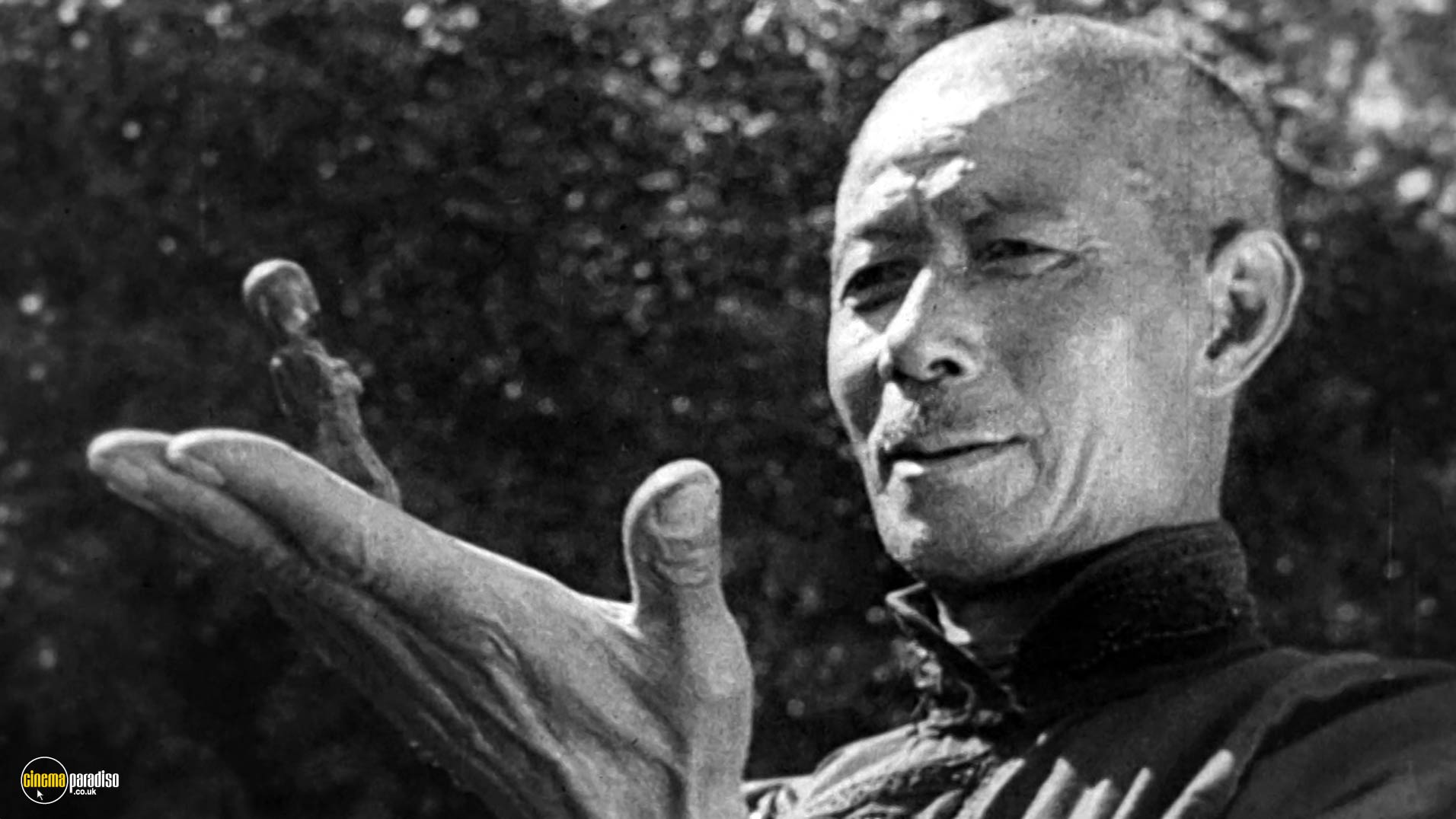

It is tempting, though, to think of his early films as being gritty social dramas about marginalised people in cramped urban dwellings, while the later ones deal with the residents of wind-tossed, rain-swept, mud-spattered villages being exploited by scheming interlopers. Film Comment called Tarr 'the bleak (and bleakly funny) maestro of modernist black-and-white ruin' who 'turned the post-communist landscapes of Hungary into elemental playgrounds of loneliness and decay. His films are populated by smoke, fog, and rain as much as the weathered faces of his brooding, binge-drinking protagonists.' But it wasn't just the look of Tarr's pictures that was so distinctive. They also took their time and made exacting use of carefully choreographed long takes. As A.O. Scott of The New York Times put it, there was 'something ancient and ageless' about Tarr's style, as though he was 'a medieval stone carver who happened to get his hands on a camera'.

Despite examining what appeared to be human fragility and the futility of existence in bleak pictures, which, from 1987, were invariably shot between November and March to ensure lowering weather conditions, Tarr always insisted that his films were comedies, like Anton Chekhov's plays. Refusing to use storyboards or stick rigidly to the script, he honed in on seemingly insignificant details in the mise-en-scène and highlighted the best and worst human characteristics to expose the 'wonder, anguish, and mystery' of life. It's safe to say, we shall never see his like again.

First Flickerings

Béla Tarr was born on 21 July 1955 in the southern university town of Pécs. Along with his brother, György (who would go on to become a painter), Tarr grew up in Budapest, where father, Béla Tarr, Sr., designed stage scenery and mother, Mari, worked as a theatre prompter for almost 50 years. At the age of 10, Béla, Jr., attended a casting session for Hungarian National Television and landed the role of Vasya, the protagonist's sensitive son, in a 1965 production of Leo Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich. He didn't become a child star, however, although he did later take cameos as a director in a bar in Gábor Bódy's Dog's Night Song (1983) and as an asylum patient who believes he's Jesus Christ in Miklós Jancsó's Season of Monsters (1986).

On his 14th birthday, Tarr received an 8mm camera from his father and he immediately started making short films. At the age of 16, he followed the example of Jean-Luc Godard and named a film-making collective, Dziga Vertov, after the Soviet creator of kino-eye newsreels and the classic city symphony, Man With a Movie Camera (1929). The group's first film, Guest Workers (1971), was a profile of Romani labourers seeking permission to work in Austria. However, the authorities heard about this subversive study after it won a prize at an amateur festival and it mysteriously disappeared after Tarr was questioned about criticising leader János Kádár. No charges were levelled, although he was denied entry to university to study philosophy. By seeking to punish Tarr for his perceived activism, however, the Communist Party merely pushed him towards the medium through which he would be able to express his criticism most effectively.

Until then, Tarr had merely considered cinema a hobby. But he continued to make films while he took work as a labourer and a caretaker at a state-run House for Culture and Recreation, while also operating as 'a free-lance intellectual'. Tarr also toiled at a shipyard, which gave him the time to work as an assistant on István Dárday and Györgyi Szalai's semi-documentary, Film Saga (1977). He also directed his own short, Hotel Magnezit (1978), which centres on an ageing man who is thrown out of his hostel digs after being accused of stealing a motor from the factory where he works. Running 12 minutes, this can be found on YouTube, as well as on Béla Tarr: A Curzon Collection, a limited eight-disc Blu-ray boxed set that also includes Cinemarxisme and Diplomafilm (both 1979).

We'll hear more about the latter and Tarr's college days below, but the former is an intriguing exercise in raw Dárdayesque realism that keeps the camera intrusively close to three people involved in the shooting of a commercial for Fabulon body lotion. The actress curses the fact that she slept with the director for such a badly paid role, while the man who makes the lotion sheepishly admits to sneaking off to the cinema twice a month with his mistress and the cleaning woman, left to tidy up after everyone has gone, who complains about the lack of respect shown by the husband who has come to rely on her since losing a leg.

All three performers were non-professional and Tarr admitted that he bent the rules of his assignment by tinkering with actuality. 'The truth is,' he told an interviewer, 'I can honestly tell you, I've never made a documentary in my life. I never could. Once in college I was supposed to make a documentary and it didn't turn out to be a documentary. Somehow, I was always more aggressive, more violent than I could make a documentary. It takes so much humility, so much strength to stop manipulating things, which is impossible, because just by going into a situation with a camera, you've already decided that the situation has changed, because it's no longer happening as if you weren't there. In this case, let it be the way I want it to be.' Things would be the way Béla Tarr wanted them to be for the next three decades.

DIY Realism

Tarr's shorts might have upset the authorities, but they impressed those running the Béla Balázs Studios, an outlet for experimental film-making that was named after the celebrated Hungarian film theorist (1884-1949), whose screenwriting credits included G.W. Pabst's The Threepenny Opera (1931) and Leni Riefenstahl's The Blue Light (1932). Among the studio's leading lights were the avant-gardist, Gábor Bódy, and the documentary-making duo of István Dárday and Györgyi Szalai, who were key members of the Budapest School that would profoundly influence Tarr's early work.

'I loved the cinema always,' Tarr would reveal years later, 'and I loved to go watch movies. But what I saw there was just stupid lies and fake stories. I never saw life and I never saw anything about the people I knew. I never saw real passion, I never saw real emotions, or real camerawork. I never saw a real movie. I thought, if they cannot show me, then I have to do my movie.' This was easier said than done, however, as Hungary's state-controlled film industry required directors to have a diploma from an approved course. But the board at the Béla Balázs Studios recognised Tarr's talent and gave him a budget of around $100,000 and a five-day schedule to enable the 22 year-old to complete his debut feature, Family Nest (1977), while recovering from a back injury that he had sustained during his three-year shipyard stint.

The story is deceptively simple and centres on Irén (Irén Szajki), a young wife who has been living in a one-room apartment with her in-laws (Gábor Kun and Gáborné Kun). When her hopes of finding their own place are frustrated by red tape, Irén urges husband, Laci (László Horváth), to take her side against his parents. However, they have suggested that Irén had been unfaithful during their son's absence and the tensions within the cramped abode start to spill over.

Mostly shooting his non-professional players in mediums and close-ups, Tarr reflected ideas from both Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Jean-Luc Godard to convey a feel of everyday life, as the characters squabble over fidelity, family honour, domestic responsibility, gender expectations, and belief in a system that has created the housing shortage that forces them to live in such difficult conditions. One shocking sequence shows Laci and his mate rape a Romani friend of Irén's, only for them all to end up going for a drink together.

When asked about finding his cast, Tarr replied: 'I knew them from before I started the movie. I was close to these kinds of people. I was working in a ship factory, and was always close to the ugly, miserable proletarians. I just wanted to show their day-to-day routines, their striving for a better life.' His efforts impressed the jury at the Mannheim-Heidelberg Film Festival, as Family Nest shared the Grand Prize with Leon Ichaso and Orlando Jiménez Leal's El Super (1979). Moreover, the Party relented and awarded Tarr a place at the University of Theatre and Film Arts in Budapest, where he met Ágnes Hranitzky, who would become his partner, regular editor, and occasional co-director.

While at college, Tarr assisted Dárday and Szalai on Stratagem (1980), which pitted a village doctor against the local authorities in a scheme to build a social welfare home. Watching the co-directors in action had a profound influence on Tarr when he came to make his second feature, The Outsider (1981), which also invited comparisons with the work of John Cassavetes (even though Tarr claimed not to have seen any of the American's films at that point).

Having been kicked out of music school in Debrecen, violinist András (András Szabó) comes to Budapest to work in a rundown psychiatric hospital. Despite having a child with another woman, he marries Kata (Jolán Fodor) and moves into a tiny flat. Drinking heavily, András starts mistreating the patients and is fired. Consequently, even though he becomes a part-time DJ, the couple have to move in with his parents and the increasingly disillusioned Kata grows close to her husband's prodigal brother, Csotesz (Imre Donkó).

As in Family Nest, Tarr pulls no punches when it comes to depicting daily life under an authoritarian regime. However, he ponders here the extent to which those on the margins of society are victims of an uncaring system or whether they have inflicted their situation upon themselves. Nicknamed 'Beethoven', the reckless and irresponsible András certainly doesn't help himself, as he rides roughshod over the feelings of others in a boozy haze.

Once again working with non-professional actors and keeping the camera close to the unrelenting action, Tarr was delighted with his cast. 'You have to understand,' he told one interviewer, 'that it doesn't matter if I'm working with a big film star, or someone from the next factory. I'm looking for their personality, how they react...And when I choose them, I'm searching for how they are, like real human beings. When I get into real human situations in a scene, I want them to react how they would in their lives. They have to be natural, they have to be dancers. If someone is acting in my movies, I become mad and I stop them and say, "OK, this is nice, what you're doing, but not in this movie. I'm interested in what is happening inside of you."' Putting it more graphically, he explained why he worked in such an uncompromising way: 'There were a lot of s**t things in the cinema, a lot of lies. We weren't knocking at the door, we just beat it down. We were coming with some fresh, new, true, real things. We just wanted to show the reality - anti-movies.'

Although working in monochrome and with professional actors for the first time, Tarr continued in the much the same vein in The Prefab People (1982), which is currently the only feature not available to rent from Cinema Paradiso. Recycling ideas from Diplomafilm (with which it shares several actors), this downbeat saga completes a 'proletarian trilogy' that was notable for its overlapping dialogue, brisk cutting, and the restless handheld imagery of co-cinematographers, Ferenc Pap and Barna Mihók, who worked in natural light with muted colours to convey the confining clutter of the settings and the sense of entrapment and ennui experienced by the characters.

Young couple, Férj (Róbert Koltai) and Feleség (Judit Pogány), live in a nice flat with their two children. However, the strain of family life prompts Férj to leave and his wife looks back on their relationship while doing the household chores while he's working at the nearby factory. Quarrelling whether they're spending the day at the pool or celebrating their wedding anniversary, the pair seem to reach a crossroads when Férj leaves Feleség alone with the kids to take up a post abroad. The trial separation doesn't work out, however, and they mark their reunion by buying a washing machine, although neither looks overjoyed at the prospect of renewed marital bliss.

Eager to work with Pogány and Koltai because they were together in real life, Tarr consciously shifted away from socio-political comment (despite still skewering capitalism) to focus on human connections. Nevertheless, The Village Voice still called it an 'unrelenting, smell-the-sour-breath portrait of a blue-collar marriage dissolving under pressure from Communist-era poverty, masculine inadequacy, and restless depression'.

Not renowned for springing surprises, Tarr caught the critics off guard with a television reimagining of William Shaksespeare's Macbeth (1982). The opening prologue, featuring the three witches, ran for five minues. But the next 57 minutes were contained inside a single shot, which also condensed the action of the Scottish Play by focussing solely on the incidents directly involving Macbeth (György Cserhalmi) and Lady Macbeth (Erzsébet Kútvölgyi). Selecting a long, torch-lit cellar inside Buda Castle, Tarr rehearsed the cast and cameramen Ferenc Pap and Buda Gulyás for several days before doing around 10 takes of the prolonged scene, at the rate of two a day. 'When I went to film school,' Tarr later explained, 'my professor said I had to do a kind of examination, and shoot something not in my style, something that's classical. I was thinking, OK, I can do Macbeth. He was very surprised. But anyway, I did it, and really loved to do it. I loved to do it because my same mania came up. What is the relation between the man and the woman? What is happening within them? We cut out about half of the drama, because I was only focusing on these two people. What are their interests, what is their sexuality? A lot of things came up. And of course I did the whole movie in one take. Because it was video and we could do it. I enjoyed it!'

This little-seen teleplay (which forms part of the Curzon Tarr Collection) marked a change of approach. Henceforth, Tarr would adopt the more expressively experimental style that would become his trademark. The shift was even more pronounced in Autumn Almanac (1984), a Chekhovian chamber drama-cum-character study that opened with a quotation from Alexander Pushkin and proved to be the last feature Tarr photographed in colour. 'It was shot in a real flat,' he divulged, 'which I used like a studio. We wanted it to look fake, like a cathedral of lies. About each person's interests and how they betray each other and fight with each other. And how the f**king money and these interests destroy the human condition.'

The apartment is owned by Hédi (Hédi Temessy), an elderly woman who lives with her son, János (János Derzsi), and her caregiver, Anna (Erika Bodnár). However. Anna's lover, Miklós (Miklós B. Székely), has wormed his way into the household, which is completed by János's impoverished former teacher, Tibor (Pál Hetényi). At first, everyone rubs along happily. But János is worried about money, as is Pal, who needs quick cash to pay off a creditor. When he steals and pawns Hédi's gold bracelet, he finds himself at odds with the other residents, even Anna, who has slept with Pal, as she has with Miklós and János, to add to the growing sense of tension.

As harmony breaks down, Tarr stages the action as a series of two-handed dialogues that take place in various rooms around the house. The pervading air of pessimism hardens into despair, distrust, and detestation, as Tarr. production designers Ágnes Hranitzky and Gyula Pauer, and cinematographers Ferenc Pap, Buda Gulyás, and Sándor Kardos experiment with colours, lighting, angles, and props in showing how trapped and isolated the characters are. At one point, the entire set tilts, while the film ends with a bitingly sardonic rendition of 'Whatever Will Be Will Be (Que Sera Sera) '. The remainder of the music is provided by Mihály Vig, who would become a key member of the Tarr troupe. Ágnes Hranitzky's editing is also teasingly precise, although her input could be felt across the board. 'I have a say in everything,' she once claimed, 'but it's always Béla who has the creative initiative.' As he puts it: 'It's quite simple. I set most things up, in terms of the location and the set. Since the beginning, I prefer that she is there because everything happens once you get to the location, and she has a very sharp eye. She can always see if something is wrong. It's more helpful to watch a film with four eyes, not only with two.'

The Mutual Auteur

In the mid-1980s, Kodak ditched celluloid and started using a polyester-based material for its film stock. Béla Tarr heartily disapproved. 'Those polyester colours are fake,' he declared. 'The red is too red. The yellow is too yellow. And when you are doing the grading, you become mad because you cannot find the right dramaturgy for the colours.' As a consequence, he never shot another feature in colour and, in switching to monochrome, he hired a new cinematographer in Gábor Medvigy.

Having written his first films alone, Tarr also forged a bond with novelist László Krasznahorkai, whose elaborately complex sentence structures would influence the drift to what is often called 'slow cinema', although this had already been practiced to varying degrees by Michelangelo Antonioni, Andrei Tarkovsky, Theo Angelopoulos, and the first Hungarian master of the long take, Miklós Jancsó, whose best work can be rented from Cinema Paradiso, largely through the excellent Second Run label: My Way Home (1965), The Round-Up (1966), The Red and the White (1967), Silence and Cry (1968), The Confrontation (1969), Agnus Dei (1970), Red Psalm (1972), and Electra, My Love (1974).

Tarr and Krasznahorkai would collaborate for the first time on Damnation (1988), which opens on a lengthy shot of coal skips being carried along a cable above the rain-sodden mining town in which the melancholic Karrer (Miklós B. Székely), who had driven his wife to suicide, moons over the torch singer (Vali Kerekes) at the Titanik bar. She harbours dreams of becoming famous and tries to distance herself from Karrer, who spots an opportunity to get rid of her husband, Sebestyén (György Cserhalmi), when Willarsky (Gyula Pauer) the bartender asks him to deliver a package and he delegates the task in the hope of making his move.

With fog swirling and mud sticking, this is a place to sap the spirits and reinforce Karrer's loathing of children because they give people the will to carry on when there's clearly no point. Deriving no pleasure from having seduced his beloved, he commits an act of treachery that leaves him so bereft that he gets down on all fours in a downpour at the rubbish tip to bark in the face of the dog that has been annoying him. Name a Hollywood noir in which that happens - although plot is not Tarr's focus in this bid 'to understand everyday life' through the depiction of human misery. There's a jauntiness to the accordion music composed by Mihály Vig. but no one in the bar has any fun, as they are all sinking on their very own Titanik.

Such grinding realism was calculatedly artificial, however, as Tarr constructed his setting from seven different locations and had a number of buildings erected to exacting specifications, so that even the texture of the walls could contribute to the overall sense of crushing ennui. Unsurprisingly, the Party was less than impressed by Tarr's depiction of its regime and he left for Berlin after being informed that he would not be allowed to work in his homeland. While in exile, he drew on a Krasznahorkai short story for 'The Last Boat', his 30-minute contribution to City Life (1990), a four-hour portmanteau picture that also included work by Alejandro Agresti, Gábor Altorjay, José Luis Guerín, Krzysztof Kieslowski, Clemens Klopfenstein, Tato Kotetishvili, Ousmane William Mbaye. Eagle Pennell. Carlos Reichenbach, Dirk Rijneke, Mrinal Sen, and Mildred Van Leeuwaarden.

Tarr also lingered on the vast puszta grasslands for Journey on the Plain (1995), a documentary short about the Great Hungarian Plain that would provide the setting for several of his key later works. German cinematographer Fred Kelemen shot the colour images, which were counterpointed by the poems of Sándor Petofi, the ambient sound of György Kovács, and the music of Mihály Víg. This exquisite miniature is available on the Curzon Blu-ray collection, but it has been somewhat overshadowed by its epic predecessor.

Based on a Krasznahorkai novel, Sátántangó (1994) had been on Tarr's radar since 1985. However, he had to wait for the fall of the Iron Curtain to make the 415-minute film, which follows its source in being structured like a tango, with six chapters going forward and six going back. Although a script was prepared to help the producers raise funding, much of the action was improvised on the set. But the production took over two years to complete because, as Tarr explained, 'We could not shoot in the summer, because of the leaves on the trees, and we could not shoot in the winter, because of the snow. We could only shoot early spring or late autumn.'

Following an eight-minute opening shot of cows wandering across the market square of a small puszta village and out into the countryside beyond, the sprawling action centres briefly on Futaki (B. Miklós Székely), who overhears Schmidt (László feLugossy) plotting to defraud his neighbours of the money they had earned following the collapse of their collective farm. The Doctor (Peter Berling) also witnesses the conversation, but he is a reclusive character who rarely leaves home.

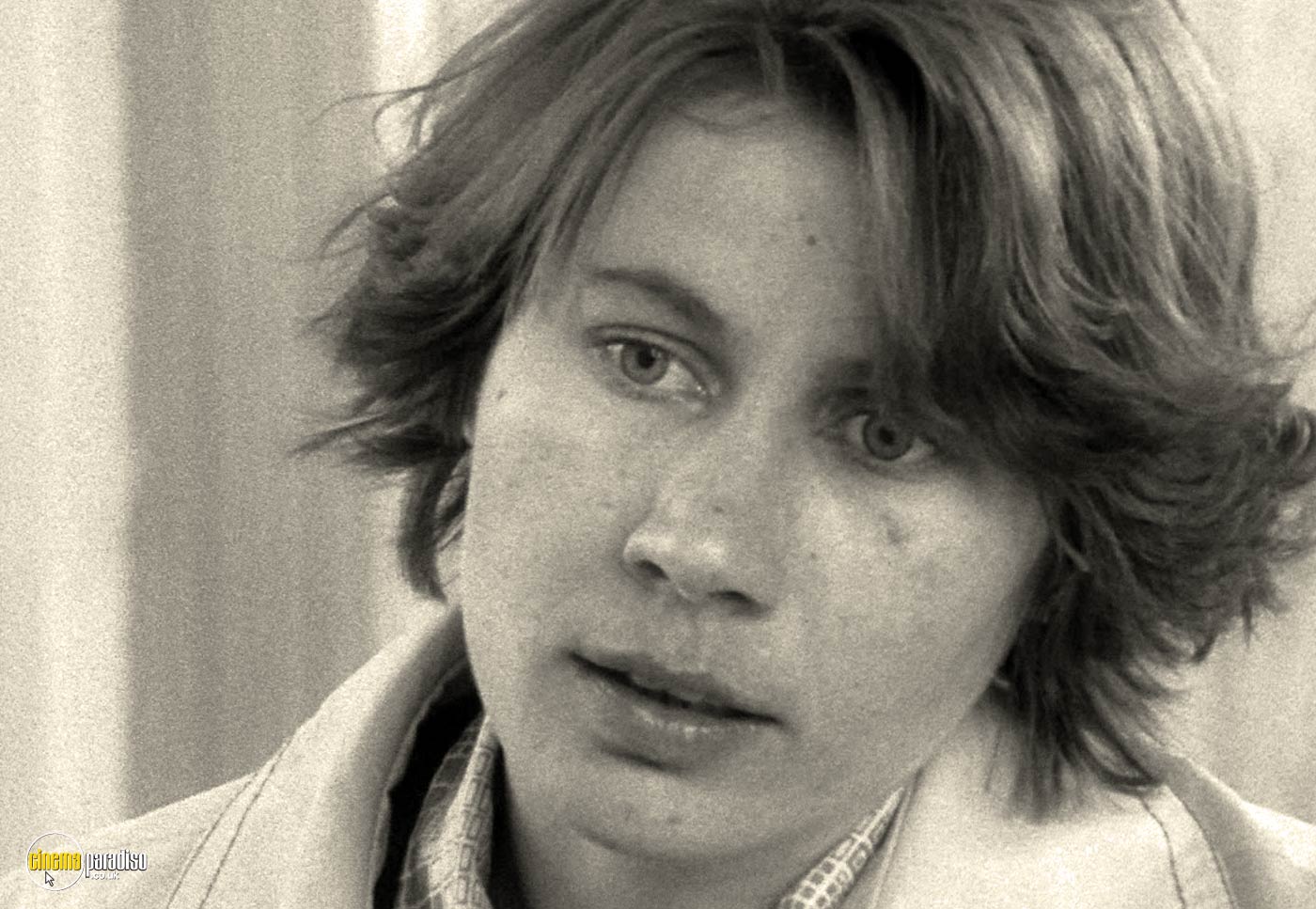

Rumours are rife that former farm workers, Irimiás (Mihály Vig) and Petrina (Putyi Horváth), who had long been presumed dead, are going to return to the village. The scurrilous Sanyi (András Bodnár) is in cahoots with the pair and he tricks his younger sister, Estike (Erika Bók), into killing her cat to ensure that her money tree flourishes. When he steals her cash, the girl kills herself and her funeral is taking place when Irimiás and Petrina arrive. The Doctor feels guilty about Estike, as he had seen her outside the bar when he had ventured out to buy some pear brandy. However, he had wound up in hospital after being found in the woods and has no idea that his neighbours have been duped by Irimiás into parting with their savings and leaving the village. Perplexed by the supposedly broken bell tolling in the church tower, the Doctor discovers a madman warning about the imminent arrival of the Turks. Frightened, the Doctor returns home and starts writing the words with which the film began.

Obviously, this is only a brief outline and can't possibly convey how Tarr employs only around 150 shots over seven and a half hours at a time when the average 90-minute Hollywood feature contained 1100 shots. But story matters much less than mood, as Tarr ruminates on the breakdown of authority, the mendacity of false prophets, the curse of avarice, and the folly of indifference. Given Hungary's trajectory between the end of the People's Republic and the rise of Orbánite populism, many have put an historical spin on the picture. But Tarr insisted that his themes were 'cosmic' rather than political and that he was more interested in the 'presence' of his characters than in their thoughts and actions. He allows Kelemen's camera to linger on seeming incidentals like the state of the ground and the condition of the walls, while he spends as much time watching a protracted dance sequence as he does charting the consequences of the sinister prodigal's return. When questioned about the film's meaning, Tarr averred, 'When we are making a movie, we only talk about concrete situations - where the camera is, what will be the first and the last shot. We never talk about art or God.'

American critic, Susan Sontag, famously gushed, 'Devastating, enthralling for every minute of its seven hours. I'd be glad to see it every year for the rest of my life.' But Peter Hames was more incisive when he called Sátántangó 'a slap in the face of consumerism and corporate taste', as it held up a mirror to democratic Hungary and its people. Tarr would take a three-year break after this Herculean enterprise, although he returned to consider some similar concepts in the 145-minute adaptation of Krasznahorkai's 1989 novel, The Melancholy of Resistance, which Tarr dubbed 'a kind of fairy tale'.

Set in a desolate provincial town, Werckmeister Harmonies (2000) centres on János Valuska (Lars Rudolph), who is devoted to György Eszter (Peter Fitz), a musicologist who is intrigued by the ideas of the 17th-century Baroque theorist, Andreas Werckmeister. György is estranged from his wife, Tünde (Hanna Schygulla), who is having an affair with the local police captain (Péter Dobai). Disquiet spreads around the town after a Circus Master (Ferenc Kállai) arrives with his prized attraction, a stuffed whale, which he puts on display in the square. His star performer, The Prince (Sandor Bese), whips up the residents into a frenzy and György's cobbler brother, Lajos (Alfréd Járai), is killed during the ensuing riot. János is committed to a psychiatric ward, where György visits to inform him that he has been evicted from his house by Tünde and the police chief. However, he hopes they can live happily in the garden shed with his piano.

Once again pondering the impact of an interloper on a remote provincial community, this has considerably more plot than its predecessor. But Tarr requires only 39 shots to chronicle the town's implosion, with the arrival of the whale through the misty dusk light and the mob attack on a hospital being the standout set-pieces. German icon Hanna Schygulla was the first famous actor that Tarr had worked with, although her dialogue was spoken by Marianna Moór. Lars Rudolph and Peter Fitz were respectively dubbed by Tamás Bolba and Péter Haumann, with Rudolph having been a street musician when Tarr spotted him in Berlin. Such was the protracted nature of the shoot, however, that Rudolph had attracted critical attention in Stefan Ruzowitsky's The Inheritors, Tom Tyker's Run Lola Run (both 1998) and The Princess and the Warrior, and Oskar Roehler's No Place to Go (both 2000) by the time Werckmeister Harmonies was released.

Taking three years to complete, this difficult production came to seem like a cakewalk compared to The Man From London (2007). After Tarr had contributed 'Prologue' to the 2004 anthology, Visions of Europe, he embarked upon this Franco-German-Hungarian picture, which had been all set to go when producer Humbert Balsan committed suicide in February 2005. As a number of backers promptly withdrew, Tarr was only left with enough money to shoot for nine days in Corsica. While deals were done to provide emergency funding, it emerged that the rights to Georges Simenon's source novel had reverted to a French bank, which took a year to agree terms to allow Tarr to proceed.

He had been interested in the novel for over 20 years, although he seems not to have seen two previous adaptations, Henri Decoin's L'Homme de Londres (1943) and Lance Comfort's Temptation Harbour (1947). When asked about his adaptation, Tarr had replied: 'It's not an adaptation, I just loved the atmosphere of the novel. I read Simenon's novel 20 years ago, and I only remember it for the atmosphere, images of a man over 50, who has a very monotonous daily life, with no chance for change. He sits in his cage alone, while the city is sleeping during a dark night. He is a really lonely man. I just wanted to do a movie about the loneliness. Someone over 50 who has no chance. And what happens when he gets that chance, a temptation.'

Adding production designer László Rajk to his usual crew, Tarr was planning to use István Szaladják as his new cinematographer. However, he quit just two days before the shoot was due to start and Tarr asked Fred Kelemen, whom he had taught briefly at the Berlin Film Academy, to drop everything and join him. Another late addition was Tilda Swinton, as Tarr had been agonising over who should play the role of protagonist's wife and he had been frustrated when the photo of his ideal candidate was only labelled with an ID number and not a name. Having not recognised Swinton, he was surprised when the mystery was solved and delighted when she accepted his invitation to join the cast.

One night, while pointsman Maloin (Miroslav Krobot) is on duty in the viewing tower at a small French port's railway terminus, he sees a man with a briefcase fall into the dock after a struggle. Retrieving the case, Maloin discovers that it's full of British banknotes and decides to hide it. Snapping at wife Camélia (Tilda Swinton) and daughter Henriette (Erika Bók) over supper, Maloin intuits that Brown (János Derzsi), the man who had killed the stranger, has realised that the tower overlooks the waterfront. However, Brown also has to factor in the arrival of Morrison (István Lénárt), a detective acting on behalf of a London theatre owner who is prepared to offer a generous reward for the return of the £55,000 stolen from his safe.

Tarr was fascinated by the story because 'it deals with the eternal and the everyday at one and the same time. It deals with the cosmic and the realistic, the divine and the human, and to my mind, contains the totality of nature and man, just as it contains their pettiness.' But, even though Ágnes Hranitzky was credited as co-director, the critics were largely underwhelmed, with Variety opining that this would define the debate between those who saw Tarr as 'a visionary genius' and those who claimed he was 'a crashing bore'. The New York Times dismissed the picture as 'bloated, formalist art', while The Village Voice denounced it for standing 'as an example of style for the sake of pure and intense but dispassionate style'. We at Cinema Paradiso would beg to differ, however, as this is one of the most visually striking noirs in screen history. It's just a shame that the earlier versions aren't available on disc for comparison.

Whether or not the exertions in getting his previous two films made took their toll, Tarr decided that The Turin Horse (2011) would be his last. Once again, Hranitzky shared the directing credit, while László Krasznahorkai worked on a screenplay that was based on an anecdote about Friedrich Nietzsche that had fascinated the pair since they had first met in 1985. The German philosopher had been in Turin on 3 January 1889 and been so incensed at witnessing a cabby whipping a horse that refused to move that he had jumped on to the footplate and thrown his arms around the creature's neck and started sobbing. A friend had escorted Nietzsche home, but the incident left such an impression that he rarely spoke again during the last 11 years of his life after uttering the phrase, 'Mother, I am stupid,' two days after his equine intervention. What interested Tarr and Krasznahorkai was not the philosopher's incapacity, however, but what had happened to the horse.

The question came up again during the shooting of The Man From London and the resulting story was perhaps the bleakest of Tarr's career. As he said himself, 'All my movies are comedies! Except The Turin Horse.' Indeed, following the opening narration outlining the Nietzsche episode, there is no dialogue for the next 20 minutes, as 19th-century farmer, Ohlsdorfer (János Derzsi), sits with his daughter (Erika Bók) in a shack on the wind-strafed puszta. They learn from their neighbour, Bernhard (Mihály Kormos), that the nearby town has been destroyed and they decide to leave their home after a confrontation with a band of Romani travellers over access to their well. However, as Ohlsdorfer's horse refuses to work, they have to turn back because pushing the cart containing their meagre possessions proves too arduous. Leaving the horse in the barn, father and daughter are cast into darkness as the sunlight disappears and they are left to subsist on raw potatoes while awaiting their fate.

Composed of just 30 shots, this is both gruelling and gripping, as Tarr leaves us to wonder as much about what happens to Schrödinger's horse in the barn as to the hapless Ohlsdorfers, who manage to make each other miserable while being incapable of avoiding the inevitable. Tarr had said, 'I want to make one more film about the end of the world, and then I will stop making films,' and he repeats the promise several times during Jean-Marc Lemoure's documentary, Tarr Béla, I Used to Be a Filmmaker (2013), which offers revealing insights into the Hungarian's working methods and the nature of his collaborative dependence not just upon Ágnes Hranitzky and Fred Kelemen, but also upon the crew members who built an authentic farmhouse in the middle of nowhere, the grips who operated the wind machines, and those who tossed detritus into the gusts to create the impression of an end-of-days tempest.

Tarr himself felt the door closing on his career: 'In my first film I started from my social sensibility and I just wanted to change the world. Then I had to understand that problems are more complicated. Now I can just say it's quite heavy and I don't know what is coming, but I can see something that is very close - the end.' His sentiments were somewhat echoed in A.O. Scott's review for The New York Times: 'The movie is too beautiful to be described as an ordeal, but it is sufficiently intense and unyielding that when it is over you may feel, along with awe, a measure of relief.' But Tarr was adamant that his brand of film-making was superior to the fare being churned out for mainstream consumption: 'Most films just tell the story: action, fact, action, fact...For me, this is poisoning the cinema because the art form is pictures written in time. It's not only a question of length, it's a question of heaviness. It's a question of can you shake the people or not?'

The 56 year-old had spent his life trying to 'shake' audiences and he bowed out with the Grand Jury Prize at the Berlin Film Festival. In an interview with a Hungarian newspaper, he defended his approach to cinema: 'A man gets up at four in the morning, gets dressed, drives in the dark to get to the filming location by six. It's dark, it's cold, it's windy. It's raining...An actor shows up, hung over and has a thousand problems. If I didn't think you were all going to watch it, then why the hell would I do all this? I'm not a masochist.' In a variation on the theme, he insisted that he had always striven to speak to viewers in their own language and deliver what they could appreciate. 'You have a responsibility to the people,' he said, 'and you cannot cheat them. When you are waking up at four o'clock in the morning and you have to be on the set at 5:15, you are just thinking about how you can do your best, because the audience is intelligent and sensible. I respect them. This is a moral question. I have to surrender, and I have to do my best for them. They are my partners. When I'm working, my ego is nowhere.'

By 2011, however, Tarr felt he had nothing more to communicate. 'I was developing my own language, my film language,' he told a reporter. 'I went deeper and deeper...with The Turin Horse, I arrived at the point where the work is complete, the language is done. I don't want to use my film language for repeating something. I can't. I don't want to be boring.' He confirmed his decision at the New York Film Festival: 'Seriously, this is my last movie. Filmmaking is a nice bourgeois job. I can make ten or fifteen more movies. I can repeat myself, but I do not want to. I do not want to make copies just to make money. I respect the audience, and I respect my work. And I have the feeling that the work is done. I have no reason to do more...I want to protect my work, from myself too.'

Thirteen years later, he confided in The Guardian that he had made the right decision: 'We had made everything we wanted. The work is done, and you can take it or leave it.'

Tarr Very Much

Although he stopped making feature films, Tarr did not necessarily go into retirement. In January 2011, he joined the board of the human rights group, Cine Foundation International, and spoke out boldly when Iran imprisoned film-makers Jafar Panahi and Mohammad Rasoulof. In an open letter, Tarr wrote: 'Cinematography is an integral part of universal human culture! An attack against cinematography is desecrating universal human culture! This cannot be justified by any notion, ideology or religious conviction!' He went on to advocate on behalf of Panahi. 'Jafar did not do anything else than what is the duty of all of us; to talk honestly, fairly about our own country and loved ones, to show everything that surrounds us with tender tolerance and harsh austerity! Jafar's real crime is that he did just that; gracefully, elegantly and with a roguish smile in his eyes! Jafar made us love his heroes, the people of Iran; he achieved that they have become members of our families! WE CANNOT LOSE HIM! This is our common responsibility, as despite all appearances we belong together.'

Such powerful and clear-sighted statements continue to resound 15 years later. Considering himself to be an anarchist atheist, Tarr wrote equally potently on the subject of migration. 'We have brought the planet to the brink of catastrophe with our greediness and our unlimited ignorance. With the horrible wars we waged with the goal of robbing the people there...Now we are confronted with the victims of our acts. We must ask the question: who are we, and what morality do we represent when we build a fence to keep out these people?'

He also railed against right-wing populism. 'Trump is the shame of the United States,' he proclaimed in a 2016 interview. 'Mr Orbán is the shame of Hungary. Marine Le Pen is the shame of France. Et cetera.' In December 2023, Tarr joined 50 other film-makers in demanding a ceasefire and an end to the killing of civilians in the Gaza Strip, while also calling for a release of the hostages and the opening of a humanitarian corridor for the passage of aid.

As the newly elected president of the Association of Hungarian Film Artists, Tarr's love of cinema and faith in what it can achieve prompted him to relocate to Sarajevo in February 2012, where he helped found Film.Factory. With its motto, 'no education, just liberation', this pioneering film school eschewed conventional study formats and invited the likes of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Carlos Reygadas, Pedro Costa, and Gus Van Sant to teach courses.

Tarr also remained active as a producer, as his IMDB entry confirms. As far back as 2005, he had worked on Bruno Cortini and Putyi Horváth's Death Rode Out of Persia and Kornél Mundruczó's Johanna, which is available from Cinema Paradiso and centres on a recovering drug addict (Orsolya Tóth) who survives an overdose and becomes a nurse because she believes she has been given the gift of healing. Staying in Hungary, Tarr has also been credited as producer on Gyula Maár's Töredék, the multi-authored documentary, Hungary 2011 (2012), and Dorka Vermes's Árni (2023), as executive producer on the Film.Factory outing, Lost in Bosnia (2014), Graeme Cole's Murmurs (2020), Hayk Matevosyan's Lullaby of the Mountains, and Renátó Olasz's Stars of Little Importance (both 2025), and as associate producer on Sergio Flores Thorija's Waking Up From My Bosnian Dream (2017). In addition to over a dozen shorts (many of which had Film.Factory connections), Tarr also collaborated with Icelandic debutant, Valdimar Jóhannsson, on Lamb (2021), which starred Noomi Rapace and Hilmir Snær Guðnason as a couple who take pity on a bizarre hybrid sheep.

Tarr's creativity also found an outlet in a couple of gallery exhibitions. In 2017, he helped curate Till the End of the World at the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, which combined a film element, a theatre set, and an installation. Over 40,000 visitors came to see the show, while the Wiener Festwochen in Vienna commissioned Missing People (2019), which combined footage shot by Fred Kelemen with an installation and a performance involving 250 homeless people from the Austrian capital.

Having separated from Ágnes Hranitzky after their professional partnership ended, Tarr married Bosnian art curator Amila Ramovic in January 2025. However, he remained close to Hranitzky and her daughter, Reka Gaborjani, who is a literary historian. After a long illness, Tarr died in a Budapest hospital at the age of 70 on 6 January 2026. Gergely Karácsony, the mayor of Budapest and leader of the opposition to Viktor Orbán, lamented, 'The freest man I've ever known is dead.' However, he saluted him for his 'endless love for the essence of man, human dignity,' while the newly named Nobel laureate, László Krasznahorkai, declared Tarr to be 'one of the greatest artists of our time. Unstoppable, brutal, unbreakable.' He continued, 'When art loses such a radical creator, for a while it seems that everything will be terribly boring. Who will be the next rebel here? Who will come forward? Who will kick everything apart?' Who, indeed? Perhaps a graduate from Film.Factory? But no one ever again will create such an intellectually daring and stylistically distinctive body of work as Béla Tarr.

-

Family Nest (1979) aka: Családi tüzfészek

1h 46min1h 46min

1h 46min1h 46minIrén (Irén Szajki) is a young wife who has been living in a one-room apartment with her in-laws (Gábor Kun and Gáborné Kun). When her hopes of finding their own place are frustrated by red tape, she urges husband, Laci (László Horváth), to take her side against his parents. However, they have suggested that Irén had been unfaithful during their son's absence and the tensions within the cramped abode start to spill over.

- Director:

- Béla Tarr

- Cast:

- Irén Szajki, László Horváth, Gábor Kun

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

The Outsider (1981) aka: Szabadgyalog

2h 2min2h 2min

2h 2min2h 2minViolinist András (András Szabó) works in a rundown psychiatric hospital. Married to Kata (Jolán Fodor) and living in a tiny flat, he starts drinking heavily and mistreating the patients. When he gets fired, the couple move in with his parents, where the disillusioned Kata grows close to András's prodigal brother, Csotesz (Imre Donkó).

- Director:

- Béla Tarr

- Cast:

- András Szabó, Jolan Fodor, Imre Donkó

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Autumn Almanac (1984) aka: Öszi Almanach

1h 55min1h 55min

1h 55min1h 55minThe elderly Hédi (Hédi Temessy) lives in a cramped apartment with her son, János (János Derzsi), and her caregiver, Anna (Erika Bodnár). However. Anna's lover, Miklós (Miklós B. Székely), has wormed his way into the household, along with János's ex-teacher, Tibor (Pál Hetényi). At first, everyone rubs along happily, but cracks start to appear in the face of money worries and sexual jealousy.

- Director:

- Béla Tarr

- Cast:

- Hédi Temessy, Erika Bodnár, Miklós Székely B.

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Damnation (1988) aka: Kárhozat

2h 0min2h 0min

2h 0min2h 0minKarrer (Miklós B. Székely) is obsessed with the torch singer (Vali Kerekes) at the Titanik bar in a rain-sodden mining town. When Willarsky (Gyula Pauer) the bartender asks him to deliver a package, Karrer spots an opportunity to get rid of her husband, Sebestyén (György Cserhalmi), and make his move.

- Director:

- Béla Tarr

- Cast:

- Gábor Balogh, János Balogh, Péter Breznyik Berg

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Sátántangó (1994) aka: Satan's Tango

Play trailer6h 59minPlay trailer6h 59min

Play trailer6h 59minPlay trailer6h 59minIn a remote village on the Great Hungarian Plain, Sanyi (András Bodnár) cons his sister, Estike (Erika Bók), into planting a money tree, while spreading rumours about the return of Irimiás (Mihály Vig) and Petrina (Putyi Horváth), who were long believed dead. Meanwhile, the local doctor (Peter Berling) discovers that Schmidt (László feLugossy) is plotting to defraud his neighbours of the money they earned following the collapse of a collective farm.

- Director:

- Béla Tarr

- Cast:

- Ferenc Kállai, Mihály Vig, Putyi Horváth

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Werckmeister Harmonies (2000) aka: Werckmeister harmóniák

2h 25min2h 25min

2h 25min2h 25minJános Valuska (Lars Rudolph) is devoted to György Eszter (Peter Fitz), a musicologist whose estranged wife, Tünde (Hanna Schygulla), is having an affair with the local police captain (Péter Dobai). When a circus troupe comes to town, everyone is awed and unnerved when a giant stuffed whale is put on display and the star performer, The Prince (Sandor Bese), starts giving rabble-rousing speeches.

- Director:

- Béla Tarr

- Cast:

- Lars Rudolph, Peter Fitz, Hanna Schygulla

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

The Man from London (2007) aka: A londoni férfi

2h 14min2h 14min

2h 14min2h 14minHaving witnessed a murderous struggle on the waterfront while on duty in the watchtower of a sleepy French port's railway terminus, Maloin (Miroslav Krobot) fishes a briefcase containing £55,000 out of the dock. However, wife Camélia (Tilda Swinton) and daughter Henriette (Erika Bók) notice a change in his behaviour after he decides to keep the money, even though a London detective (István Lénárt) comes to town and the killer (János Derzsi) realises who has stolen his loot.

- Director:

- Béla Tarr

- Cast:

- Miroslav Krobot, Tilda Swinton, Erika Bók

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

The Turin Horse (2011) aka: A Torinói ló

Play trailer2h 26minPlay trailer2h 26min

Play trailer2h 26minPlay trailer2h 26minInformed by a neighbour (Mihály Kormos) that the nearby town has been destroyed, 19th-century puszta farmer, Ohlsdorfer (János Derzsi), decides to sit tight with his daughter (Erika Bók) in their remote shack. However, the rising storm and a confrontation with a band of travelling Romani prompts them to pack their meagre belongings on to their horse cart.

- Director:

- Béla Tarr

- Cast:

- János Derzsi, Lajos Kovács, Erika Bók

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-