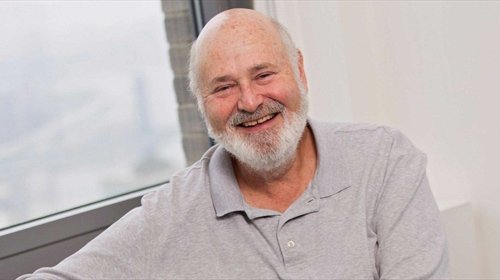

Following the death of writer-director Robert Benton at the age of 92, Cinema Paradiso looks back over a career that rarely made headlines, yet which, in its own quiet way, had a considerable influence on Hollywood in a time of change.

Robert Benton only directed 11 features in 53 years. Yet, he became one of Hollywood's finest exponents of humanist drama and, in the process, he guided eight performers to Oscar nominations, with three claiming gold statuettes. His name never appeared in the gossip columns, while he barely registered with fanboys at the glossy movie magazines who obsessed over the latest blockbusters. Indeed, he was so unassuming and inconspicuous that he once joked that he had much in common with Dracula: 'I don't leave a trace in the mirror.'

From Waxahachie to Esquire

Robert Douglas Benton was born on 29 September 1932 in the Oak Cliff area of Dallas, Texas. He later lived in University Park. But, at the age of 13, he moved to the small cotton town of Waxahachie, which had been home for five generations to the family of his mother, Dorothy (née Spaulding).

Father, Ellery Douglass Benton, worked for the telephone company. But his own family had a chequered past. One brother had been gunned down by the father of the woman with whom he had been having an affair, while the other was murdered after being chased down Main Street by a man in a Model-T Ford, who appears to have belonged to a rival bootlegging outfit. As we shall see later, the Spauldings also had their share of appalling tragedy to bear.

The young Robert was diagnosed with dyslexia and found learning difficult. As he told the Hollywood Reporter, 'Nobody knew about dyslexia in those days. If I read for about 10 minutes, I would get wired and couldn't read any more. But I could draw, and that uses the other side of the brain. So I drew and I drew and I drew. I took my identity off of that.' In another interview, he recalled, 'Actually, I couldn't read. But out of a kind of desperation I would draw and draw. I was close to being an autistic child, but drawing allowed me to extend my attention span and rejoin the world.'

In later years, Benton would claim that he only graduated from high school because his mother played bridge with the teachers. His father hated to see him struggling with his books and whisked him off to the local picture house three times a week. Benton remembered with gratitude: 'My father would come home from work and instead of saying, "Have you done your homework?", he would say, "Do you want to go to the movies?" I learned narrative from movies, not books.'

Nevertheless, Benton became the first member of his family to go to college. He enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin to study art and impressed his tutors with a series of paintings capturing disappearing aspects of Texan life. Among his classmates were Rip Torn and Jayne Mansfield and he graduated as a bachelor of Fine Arts, in spite of failing his creative writing class.

Drafted into the US Army in 1954, Benton rose to the rank of corporal and even found time during his two-year stint to paint a number of dioramas at Fort Bliss. On being demobbed, he travelled to New York to study art history at Columbia University. However, city life proved expensive and he was forced to drop out after a single term and look for work. Initially, he hoped to make a living as a cartoonist. But he wound up working as an assistant on a couple of magazines, which led to him being apprenticed to the art director at Esquire in 1957. Here, he became friends with one of the editorial staff, David Newman, as well as film critic Peter Bogdanovich, who was forever recommended foreign films at Manhattan's arthouses.

In 1958, Benton was promoted to art editor and he spent the next six years acclimatising to both the urban jungle and office life. 'It was a free-for-all,' he reflected fondly, 'so it was great training for using things from our lives in writing a movie. The magazine was always desperate to attract a bigger audience, so we were like kids trying to get attention - the rowdier and noisier we could be the better. Each week you had to come in with three or four story ideas and there'd be a brutal fight over what got accepted. It taught you to be a lot less constipated about having a bad idea or being made fun of. You'd just cut loose.'

One of Benton and Newman's most inspired pitches became an Esquire institution, the annual Dubious Achievement Awards. In addition to offering a cockeyed look back at the year's events, this unwanted accolade also put the country's great and the good in the media glare, as was happening to the British establishment during the Satire Boom that followed the success of Beyond the Fringe, which made stars of Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett, and Jonathan Miller, who would direct his former colleagues in a 1966 adaptation of Alice in Wonderland.

Benton served as a contributing editor at Esquire between 1964-72. But he didn't pursue a career in comedy, although he and Newman did spend a decade penning the 'Man Talk' column for Mademoiselle magazine. He also wrote a number of books, with The IN and OUT Book (1959) being co-authored by Harvey Schmidt, a fellow Texan who had composed the music for The Fantasticks (1960-2002), the Off-Broadway show that would go on to set the record for being the longest-running musical in American showbiz history. Having written and illustrated the children's picture book, Little Brother, No More (1960), Benton reunited with Schmidt for The Worry Book (1964) before teaming with Newman for Extremism: A Non-Book (1964), a ribald survey of left- and right-wing politics in America following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

However, during their regular movie nights with Bogdanovich, Benton and Newman had become increasingly hooked on world cinema. Benton had always admired such Hollywood stalwarts as John Ford and Howard Hawks. But, now, he fell under the spell of Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, and Federico Fellini, as well as the critics-turned-auteurs behind the nouvelle vague, the French new wave that particularly appealed to the dyslexic Benton, as directors like Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Louis Malle, and François Truffaut used the camera like a pen to tell their stories through imagery as much as through dialogue.

Nouvelle Scribe

Benton first became involved with film in 1964, when he joined forces with Elinor Jones, Tom Jones, and Harvey Schmidt to write and co-direct A Texas Romance, 1909. This short drew on photographs and letters to tell the story of a mailman (Pat Hingle), who falls in love only to lose his beloved to tragedy after their marriage. Hard to find six decades on, this stylised vignette centres on the notions of family and community that would lie at the heart of Benton's best features.

Convinced that he and Newman could make a go of writing together, Benton left his day job at Esquire and started work on a clutch of prospective scripts. Rather than sticking with film, however, the pair joined forces with composer Charles Strouse (who, sadly, also died this week at the age of 96) to write the libretto for the Broadway musical, It's a Bird...It's a Plane...It's Superman (1966). Lampooning the long-running comic-strip, Hal Prince's show was well received by the critics and drew three Tony nominations. However, the theatre-going public was less convinced and the show closed after 129 performances. In 1975, Jack Regas directed a truncated version for television, with David Patrick Wilson playing Clark Kent and Superman, as he seeks to prevent mad scientist Dr Abner Sedgwick (David Wayne) from wreaking havoc and Daily Planet hack Max Mencken (Kenneth Mars) from dallying with Lois Lane (Lesley Ann Warren).

While still at the magazine, Benton and Newman had been so impressed by Jean-Luc Godard's À bout de souffle (1960) that they decided to write an American variation. Benton later remembered, 'By chance we were reading a book by John Toland on John Dillinger, in which there's a footnote about them saying. "They were not only outlaws, they were outcasts." That appealed to us.'

As his father had witnessed the funerals of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker in Dallas in 1934, Benton knew all about the lawless duo who had evaded capture while committing a string of audacious robberies. But he was also intrigued by the fact that the pair had formed a band of outsiders with Buck Barrow and his wife, Blanche, as well as others, with C.W. Moss in the film being a composite of gang members W.D. Jones and Henry Methvin.

Although Ford, Hawks, and Alfred Hitchcock influenced their 70-page treatment, Benton and Newman also borrowed the aura of comic violence from François Truffaut's Shoot the Pianist (1960). However, as Benton disclosed, Truffaut's 1961 follow-up proved just as inspirational. ' Jules and Jim had a huge shaping influence on Bonnie and Clyde, ' he told one interviewer, 'Unlike most American movies of the time, it didn't make any moral judgements about its characters. That fit our story, because we wanted to make a movie about outlaws without treating them like psychopaths. They weren't tormented. They were people like us.'

Although they visited Texas and met people who had known the outlaws, Benton and Newman were keen for the scenario to reflect their own turbulent times. Consequently, they factored nouvelle vague gimmicks into the shooting script in a radical departure from the classical Hollywood storytelling style. They were dismayed, therefore, when Truffaut (who had helped them refine the treatment) proved too busy to direct the film and Jean-Luc Godard declined the offer to take it on. After a couple of years of touting the screenplay around the studios, the writers were relieved when Warren Beatty bought the property for $10,000, with the intention of producing alongside Arthur Penn as director. He also declared his intention to share the title roles with Faye Dunaway, while Gene Hackman and Estelle Parsons were recruited alongside Michael J. Pollard to complete the Barrow Gang.

The rest, as they say, is history. Initially dividing critics who didn't like the violence and didn't understand the new wave self-reflexivity, the picture caught the public imagination and landed 10 nominations at the Academy Awards, including one for Best Original Screenplay. Moreover, it drove a Ford V8 through the Production Code, which was abandoned after 38 years and replaced by a system of ratings that gave film-makers greater licence to depict topics in an adult manner.

Despite having helped pave the way for New Hollywood, Benton and Newman were viewed with suspicion by the studios. Returning to New York, they contributed to Kenneth Tynan's 1969 revue, Oh! Calcutta!, which became notorious for its nudity and the fact that such luminaries as Samuel Beckett, John Lennon, and Sam Shepard had written sketches. Jules Levy filmed the show for cinema release in 1972, but it was the 1976 version that made history by becoming the long-running revival (5959 performances) in Broadway history.

Eventually, Benton and Newman returned to Hollywood when Joseph L. Mankiewicz took on their script for There Was a Crooked Man... (1970), which starred Kirk Douglas as the convict seeking to break out of prison and recover his loot and Henry Fonda as the Arizona Territory warden determined to stop him. Frustratingly, this rousing revisionist Western proved to be only a moderate success and Benton and Newman had to wait a couple of years before old pal Peter Bogdanovich teamed them with Buck Henry to write What's Up, Doc? (1972), an update on the screwball comedy format that starred Barbra Streisand and Ryan O'Neal in roles very similar to those taken by Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant in Howard Hawks's Bringing Up Baby (1938).

The film was a popular success and brought the partners their second award from the Writers Guild of America. But Benton had become frustrated by hawking scenarios around Hollywood only to be dismissed by big-shot directors. He decided the time had come for him to call the shots.

First Films

A reserved man who shunned the limelight, Benton had found it difficult acclimatising to the film world. Yet the buzz of making movies proved irresistible. 'I had been terrified after Bonnie and Clyde,' he once recalled. 'That was like a whirlwind that took over everyone's life - like somebody slipping you LSD in your tomato soup, and you start to hallucinate all this stuff, and then you miss it when it's gone and think you're never going to get it again.'

Encouraged by Paramount president, Stanley R. Jaffe, Benton made the transition to directing with Bad Company (1972), which he co-scripted with David Newman. Fleeing the Civil War, Jake Rumsey (Jeff Bridges) and Drew Dixon (Barry Brown) were respectively based on Newman and Benton, although they were also intended to strike a chord with those young Americans dodging the Vietnam draft. Benton claimed there was also an element of Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist in a storyline that sought to demythologise the Old West by revealing the grimmer realities of life on the wrong side of the law.

Despite chiming in with revisionist pictures like Robert Altman's McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971), the film underperformed on the back of some positive reviews. Benton remained busy, however, as he and Newman found themselves working with the latter's wife and Mario Puzo (of The Godfather fame) on the screenplay for Richard Donner's superhero blockbuster, Superman (1978), which starred Christopher Reeve as Clark Kent and Margot Kidder as Lois Lane

After a four-year hiatus, Benton was keen to return to directing and persuaded agent Sam Cohn to show his latest screenplay to Robert Altman. He agreed to produce The Late Show (1977), which affectionately lampooned the hard-boiled Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler novels that Benton had grown to love while he was conquering his dyslexia. Art Carney excels as Ira Wells, the LA shamus who comes to regret agreeing to find the missing cat of femme fatale, Margo Sperling (Lily Tomlin). With its sardonic tone and witty repartee, Benton's screenplay was nominated for an Oscar and this classic example of New Hollywood genre revisionism should manifestly be available on disc in this country.

While making the film - which he had dedicated to his father, who had just died because he had declined to have a relatively simple operation - Benton was given a valuable tip by his producer. Vexed by the way in which Benton was giving notes to his cast, Altman took him to one side and said, 'Trust your actors. There'll come a point in the picture where they'll know more about the character than you do. Don't be an idiot - listen to them.' Taking the advice to heart, Benton became known as an actors' director, with eight of his players being nominated for Academy Awards. Two of his three winners came from his next film, which remains the crowning achievement of his career.

Benton had been hired to adapt Kramer vs Kramer (1979) from a novel by Avery Corman. However, Stanley Jaffe also asked him to direct after François Truffaut was forced to withdraw because of a scheduling issue. He was delighted, however, that the Frenchman's favourite cinematographer, Nestor Almendros, was still going to shoot the picture and they made four more together.

The director was also pleased to be working with Dustin Hoffman, who had signed to play Ted Kramer, a workaholic advertising executive who is forced to fight a custody battle for his seven year-old son, Billy, when his wife Joanna files for divorce. As he was currently going through his own separation, Hoffman initially refused the role. But, when James Caan, Al Pacino, and Jon Voight also fought shy, Benton talked Hoffman into taking the part that he later claimed had prevented him from quitting pictures and focussing on the theatre.

Kate Jackson had been cast as Joanna. But producer Aaron Spelling refused to release her from Charlie's Angels (1976-81) and Meryl Streep was hired after Faye Dunaway, Jane Fonda, and Ali MacGraw had turned the role down. 'I love Kate Jackson,' Benton later remarked. 'She would have been good. I would have been satisfied with that choice. She would have been very good because she's a wonderful actress.' But he had no idea at the time that Streep was on the cusp of becoming the finest performers in Hollywood.

One of the reasons for casting Streep was that she was still relatively unfamiliar to film-goers, in spite of striking displays in Michael Cimino's The Deer Hunter (1978) and Woody Allen's Manhattan (1979). Consequently, audiences wouldn't know what to expect of her and Benton believed this would be crucial to the success of her testimony in the courtroom scene. Convinced the lines he had written sounded too much like a man trying to get into a woman's head, he asked Streep to rewrite them from a female perspective. As she wasn't needed for the next phase of shooting, Benton had forgotten his request and was surprised when she gave him two pages of handwritten dialogue.

'It was brilliant,' he later marvelled, 'except for the fact that it was too long and we had to cut about a third of it out. When we cut it together, it was perfect: "I'm his mommy." I could never have written "I'm his mommy." That she understood - she found that. It was genius that she would find those details.' When they came to shoot the speech from various angles, Benton had to remind Streep to rein herself in during the wider and longer shots, as he wanted her emotional peak to come in the close-up.

He described the scene in an interview. 'I said, "Meryl, look, you're wonderful and I think you're great. But you haven't done that many movies and remember that this movie is gonna play in the close-up so, as they say in Hollywood, save it for the close-up. The other stuff is just mechanical" and she said "OK" and we started with a wide shot and she was so good that there was just silence when I said "Cut!" Then, I said "Meryl, please remember..." and she said, "it's OK" and [we did it] and it had the same level of intelligence and intensity. It was a brilliant performance. And she did it time and time again. By the fifth time she did it, I suddenly realised I was afraid of Meryl Streep. She was so good. I could've gone home and she would have been just as good. She just knew the character. She was brilliant.'

Young Justin Henry also took Benton by surprise, as Hoffman helped him improvise scenes like the famous ice cream showdown. All three received Oscar nominations, with Hoffman and Streep triumphing. Benton also picked up Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay, as the film took Best Picture and became a box-office hit, as its focus on divorce and single parenting had struck a chord in a country in which such things were becoming more common. Benton also won the Golden Globe and the Directors Guild Award. Yet, partway through the shoot, he had told his wife to cancel a skiing holiday they had booked because the filming was going so badly that he was certain he had a calamity on his hands. Instead, he had created what one review called the 'upmarket new-fashioned tearjerker'.

Looking back on this period, Benton joked, 'Before I directed for the first time, I remember walking down the street and thinking, "How can I direct people to just speak normally?" And later I learned, you just hire good actors.' With this thought in mind, he coaxed Streep into headlining his next project, Still of the Night (1982), which was based on a story by David Newman. Sadly, Cinema Paradiso is unable to bring you this tense, Hitchcockian thriller about the relationship between Manhattan psychiatrist Sam Rice (Roy Scheider) and Brooke Reynolds (Streep), an auction house employee who had been dating one of his patients at the time of his murder.

This would be Benton's last collaboration with Newman, but they remained friends until the latter's death in 2003. Benton opted to go solo on his next project, Places in the Heart (1984), because it drew on family history that had been running through his mind for nine years. He chose to make it when he did because he his mother had just died and he was faced with the prospect of selling the family home. Realising he no longer had a reason to return to Waxahachie, he created one in the form of a screenplay.

Originally, the story was going to centre on bootlegging and Benton did so much background research that he joked 'there was a time when I could have brewed my own liquor'. However, he felt the action was becoming too violent, so he switched the focus on to his great-grandmother, who had been widowed when her sheriff husband was shot dead by a drunk. As the culprit was Black, the neighbours had formed a lynch mob and dragged him past the house so that the family could see that tit-for-tat justice was about to be meted out.

These events had taken place in the 19th century, but Benton relocated them to the 1930s, as he could remember life in Depression era Texas. Sally Field was cast as Edna Spalding, who is left to raise her young children alone and forms a new family with her African American farmhand, Moses Hadner (Danny Glover), and Mr Will (John Malkovich), a blind war veteran who canes chairs and makes broom handles. He was based on Benton's great-uncle, while the real-life Moze had taken care of his mother while she was young. Three studios felt such details were too personal and turned the film down, even though it had been influenced by Ermanno Olmi's Palme d'or winner, The Tree of Wooden Clogs (1978). But it found a home at Tri-Star and earned Benton the Silver Bear for Best Director at the Berlin Film Festival.

His screenplay earned him a third Academy Award, while Field won a second Best Actress Oscar after prevailing in Martin Ritt's Norma Rae (1979). Despite Field making headlines, however, Benton felt this was very much an ensemble piece: 'I don't think of this movie as being about her. I think it's about all of them. I think what interested me was that her husband was taken away from her, one family unit was destroyed - and it was replaced by three people trying to survive. They were the least likely people, in that time and place, to make it - a woman, a blind man, a Black man. But they were a family. I think that we are family-making animals, but that families that result in marriages or children are not the only kind of family you make. You make professional families and other small groupings. This is the story of one of those little families. And then it's torn apart again, but it will survive that, too; they will find a way to get by.'

Stanley Jaffe praised Benton for his gift of allowing 'reality to take its time'. But it was only when he had finished editing that Benton realised he had produced something special. 'I think that when I saw it all strung together,' he told one reporter, 'I was surprised at what a romantic view I had of the past.' But the kind of films that Benton specialised in making were struggling to find a niche at multiplexes dedicated to serving up sci-fi blockbusters and action adventures to young males with disposable income. At the age of 50, therefore, Benton found himself at the peak of his powers, but also at a career crossroads.

Later Films

It has been said that Benton thrived as an outsider and struggled once he had gained admittance into Hollywood's inner sanctum. As a young screenwriter, he had helped transform the American film industry by giving it a shot of the subversive vim that had propelled the nouvelle vague. But Benton wasn't a natural iconoclast and didn't fit into the clique of movers and shakers whose achievements were chronicled in Peter Biskind's seminal 1998 study of the post-studio era, which was filmed by Kenneth Bowser as Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (2003). Thus, Benton's thoughtful stories about ordinary people enduring the vagaries of everyday life were often drowned out by the cacophony made by the franchise blockbusters that had come to dominate the box office and had put paid to New Hollywood, with its unpredictable auteurs and boat-rocking ideas.

He was also in his mid-50s and many critics felt that his Texan caper comedy, Nadine (1987), was old-fashioned. Kim Basinger and Jeff Bridges starred as estranged couple Nadine and Vernon Hightower, who are forced to go on the lam after she mistakes an envelope full of 'artistic' photographs for the dubious development plans belonging to realtor Buford Pope (Rip Torn). It's breezy stuff, with Bridges and Basinger establishing a nice screwball rapport. But the Tri-Star front office was dissatisfied and the film was cut from 88 minutes, with the version available from Cinema Paradiso clocking in at 80 minutes.

Frustrated, Benton took an executive producing berth on Peter Yates's neo-noir, The House on Carroll Street (1988), and started searching for a new project. He took the setback in his stride and confided in one reporter, 'I've just been through it so many times. Either Kramer or Still of the Night freed me. I know that if Places works, it's just a matter of time before something else doesn't. And when something doesn't, you survive. Surviving success is a lot more pleasant than surviving failure. But the object is to keep on doing what you're doing, and both great failure or great success can make that harder. The only thing that matters is just to keep on working.'

This was a lesson he had learned from one of the masters. 'After Kramer, my whole notion was to do another picture as quickly as I could, so I wouldn't get scared and let the success of Kramer start to petrify me. That was something Truffaut told me. He said, "You must go to work again as quickly as you can. The longer you wait, the harder it will be. Remember, that was just one movie. The object is to go on making pictures."'

With that mantra in mind, Benton accepted his first assignment as a director for hire. Playwright Tom Stoppard has adapted E.L. Doctow's novel, Billy Bathgate (1991), and the production got off to a bad start when the author distanced himself from the script. Next, union trouble at Disney caused costs to rise and studio chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg caused further unrest with an internal memo questioning the viability of a story set in the 1930s and turning on the relationships between young Billy Behan (Loren Dean) and gangsters Dutch Schultz (Dustin Hoffman) and Bo Weinberg (Bruce Willis).

Benton insisted on doing things his own way, however, and promptly found himself at odds with Hoffman, who was unconvinced by Dean and wanted to coach him through scenes, as he had done with Justin Henry on Kramer vs Kramer. As the film was being edited, Benton realised that it wasn't hanging together and demanded a new ending and re-shoots for a handful of key scenes. However, Hoffman was now making Hook (1991) with Steven Spielberg, while Nicole Kidman (who was playing Dutch's moll, Drew Preston) was in Ireland with Tom Cruise filming Ron Howard's Far and Away (1992). The delays caused the release date to be pushed back and gossip-seeking journalists began to sense a story. Thus, negative vibes were circulating long before the feature hit cinemas and Benton was blamed for it recouping only $15.5 million of its $48 milliion budget. He admitted it was 'a deeply unsuccessful picture' and explained, 'I'm a director of small things. It needed someone who was used to a bigger canvas.'

The three-year gap before his next outing was put down to the fact that Benton was a slow worker, who repeatedly polished his scripts before coming to the set. But his reputation had been damaged by the failure and few expected much when it was announced that he was teaming with Richard Russo to adapt his novel, Nobody's Fool (1994). Sadly, this poignant drama isn't currently available on disc. But Paul Newman excels as construction worker Donald Sullivan, who tries to cope with the death of his son with the help of landlady Beryl Peoples (Jessica Tandy, in her final role) and boss Carl Roebuck (Bruce Willis) and his neglected wife, Toby (Melanie Griffith).

Like Benton, Newman received an Oscar nomination, although neither won. They did, however, hit it off and reunited on Twilight (1998), which was also co-scripted by Russo. In the press, Newman presented a new side of his director. 'Benton's a kind and gentle man with the will of a barracuda. Don't kid yourself,' he joked. 'If he wants something, he doesn't let go of it. He's very deceptive that way - a very, very strong, tough personality. I don't think he had to display that particular gift while we were working. It showed itself in other ways. If you were trying to steal the pig knuckle off his plate or something, you were liable to end up with fork marks in your hand.'

Newman continued, 'When Benton is working best and when the actor's working at his peak, it's not that he leaves you alone; it's that he allows you the freedom to experiment and to go into odd places without crippling you before you get the words out of your mouth. The biggest gift I think that he has is when you're in trouble and are kind of lamely holding up your hand for instruction, he knows what to tell ya. Usually the problem with most directors is when you hold your hand up and they got nothing to say, or they have some kind of result-oriented thing: "Well, look to your left," or, "Don't put your face so much into the camera." That's no help when you're really, desperately trying to figure out why the scene isn't working. Benton would probably give you an active verb, like, "Crowd her." Or, "Measure her." Or, "Bait her." Or, "It's not important." You can play those things, or at least I can. I know what he's talking about.'

For his part, Benton claimed, 'The gift of getting older is the gift of making things simpler. I used to agonise over things. I worry a lot less today. You realise that what shows up in the process, that might take you by surprise, is often better than what you'd planned for.' He further elucidated, 'There's a part of me that thinks, I don't really control the film, I sort of chase after it. There's a terrific thing that happens as the film starts to take on its own life. And either you let it breathe, and you let it live, or you control it. And part of me has always loved seeing what happens in a film.'

A homage to the pulp novels that Benton had enjoyed in his youth, Twilight centres on ageing private eye, Harry Ross (Newman), who comes to live with fading movie stars, Jack and Catherine Ames (Gene Hackman and Susan Sarandon), after he gets shot in the leg while tracking down their errant daughter, Mel (Reese Witherspoon). Jack is dying of cancer and asks Harry for a favour that involves him in the mysterious disappearance of Catherine's first husband.

The critics were supportive, but the audience simply wasn't there and the film lost money. Some suggested that Benton didn't have the auteur status to command a following. But he was content with his approach to directing. 'I'm less concerned about having a style - or maybe I don't have one and I've made my peace with it. You do what you do and try not to worry about it.' He did have regrets, however: 'Because I'm dyslexic, I have a short attention span and I make short movies. I think that I've never done a picture yet that I haven't had to sacrifice something that I really loved.'

Despite having started out as a writer, Benton didn't contribute to the screenplays of his final two films. Nicholas Mayer adapted Philip Roth's The Human Stain (2003), which starred Anthony Hopkins as Coleman Silk, an academic who has been fired from his post for a supposed racist remark, and Nicole Kidman as Faunia Farley, a member of the campus staff who has an affair with Silk because her Vietnam veteran husband (Ed Harris) blames her for the death of their children.

Critics took exception to the casting of Hopkins as a light-skinned Black man passing as white. But the reviews were largely admiring of the tactful handling of difficult issues and the retention of the author's distinctive voice. However, the box-office business was modest and Benton had to content himself with serving as a writer (with Russo) and executive producer on Harold Ramis's comedy, The Ice Harvest (2005), which starred John Cusack and Billy Bob Thornton as a couple of crooked Kansas lawyers who come to regret stealing from mobster Randy Quaid.

Two years later, Benton directed what turned out to be his final feature. Adapted by Charles Baxter from his own novel, Feast of Love (2007), saw Harry Stevenson (Morgan Freeman), a community college tutor in Portland, Oregon, reflect on the many faces of love in relating the stories of café owners Bradley and Kathryn (Greg Kinnear and Selma Blair); waiter Oscar and girlfriend, Chloe (Toby Hemingway and Alexa Davalos); and estate agent Diana and her married lover, David (Radha Mitchell and Billy Burke).

Despite its fine ensemble and some touching moments, the film was dismissed as sentimental by many critics and it made little commercial impact. Benton defended his picture. 'It isn't sappy,' he told one reporter. 'In a lot of ways, it's about the downside of love, the idea that love always ends badly and yet it still seems worth doing. One reason I was attracted to the book is because you make movies to figure out things you don't know. And when it comes to love, that's something I still feel I don't really understand.' One scene, he revealed, had been inspired by a row between John Wayne and Angie Dickinson in Howard Hawks's Rio Bravo (1959). 'It's a way of showing the complexity of love,' Benton explained, 'by letting people, in the midst of a huge fight, discover how much they love each other.'

Benton had fallen for artist Sallie Rendig when they had collaborated on his children's book in the early 1960s. They worked together again on Don't Ever Wish For a Seven-Foot Bear (1972) and remained married for 60 years before her death in 2023. Benton had still been at Esquire when they started dating and a picture idea he had back in 1958 proved central to Jean Bach's wonderful jazz documentary, A Great Day in Harlem (1994), in which Benton appeared. He also cropped up in Wanderlust (2006), Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini's paean to road movies, and TCM's seven-part series, Moguls and Movie Stars: A History of Hollywood (2010).

Throughout this period, Benton kept developing potential projects. As he told one journalist, 'I've done an adaptation of Appointment in Samarra that I would really love to produce. There are several John O'Hara novels that I like very much. Richard Russo and I are talking about adapting a collection of John Cheever stories to turn into a movie. I've learned over the years that there are books that I love but I wouldn't do justice by them. I have a certain circumscribed voice and brain, and there are books that are out of my range and I should stay away from them. I look for a book that I not only love but have a true connection with and contains characters who I want to spend the next two years with. Then I enjoy being back with the actors.'

But he never got the chance to direct again. He was twice honoured by the Writers Guild of America, with the Ian McLellan Hunter Award for lifetime achievement in 1995 and the Laurel Award for screenwriting achievement in 2007. Moreover, he remained a respected voice in American cinema. When a critic reviewing a 2013 revival of Bonnie and Clyde accused the film's violent action of setting a bad example, Benton responded: 'Do you really, after seeing this movie, want to go out and be a gangster? Do you really think they had a great life? Is that something you'd choose for your child to do? I don't think so.' He continued, 'The Senate is responsible. The House is responsible. The fact that the Congress is in the hands of - being paid by - gun lobbyists. No. They want to blame it on us. But let's look at the NRA or the weapons manufacturers. Ordinary people should not be able to buy a gun that the police can't have; and I don't believe the police should have them. Maybe I have a vested interest, but no, I really don't believe that violence [is caused by the movies]. I think what these movies talked about is the fact that America is a violent country. It just is. Violence runs like a bloodline through this country, from its inception until now. I wish it weren't so, but it seems to me to be a part of us. I don't know anything to correct it, and I don't think violent movies glorify violence at all.'

While Benton kept himself busy in later years with an autobiography, he rarely watched his own films. 'Part of it is when something is done, it's done, I don't want to spend my life looking backward. It is also that when I have been forced to watch one of my films, most of what I see are the things I could have done better. For me, it's very important not to get trapped by looking backwards. I close the door and move on.' He remained, however, an avid watcher of other people's work. 'A lot of what I've learned about life,' he once revealed, 'is what I've learned, for better or worse, from movies.'

Robert Benton died at his home in Manhattan on 11 May 2025. He was survived by his son, John. Cinema Paradiso heartily recommends his films, as the early ones did so much to shape the history of recent Hollywood, while the later ones insisted on upholding conventions that are in danger of being borne away on a tide of pixels. We leave you with his wise words on re-watching a favourite film: 'Every time you see it as you get older, you see it in a different way. As you change, the movie changes with you.' Therein lies the enduring magic of cinema.

-

Bonnie and Clyde (1967) aka: Bonnie y Clyde

Play trailer1h 47minPlay trailer1h 47min

Play trailer1h 47minPlay trailer1h 47minClyde Barrow: Honey, c'mon, I wanna talk to you for just a minute. Sit down, huh? This afternoon we killed a man, and we were seen. Now, so far nobody knows who you are, but they know who I am and they gonna be coming after me and anybody who's running with me. Now it's murder, it's gonna get rough. Now look: I can't get out now but you still can. I want you to say the word to me, and I'm gonna put you on that bus back to your momma. 'Cause you mean a lot to me, honey, and I just ain't gonna make you run with me.

Bonnie Parker: No.

Clyde Barrow: Huh?

Bonnie Parker: No!

Clyde Barrow: Now look, I ain't a rich man. You could get a rich man if you tried!

Bonnie Parker: I don't want a rich man!

Clyde Barrow: You ain't gonna have a minute's peace.

Bonnie Parker: You promise?- Director:

- Arthur Penn

- Cast:

- Warren Beatty, Faye Dunaway, Michael J. Pollard

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

There Was a Crooked Man (1970) aka: There Was a Crooked Man... / The Prison Story / Hell / Hang Up

Play trailer2h 0minPlay trailer2h 0min

Play trailer2h 0minPlay trailer2h 0minParis Pittman, Jr.: [During a mealtime robbery] Ah, nothing like fried chicken while it's still hot and crispy! So the quicker you open that safe and give us the money, the quicker you can get back to that tasty-looking chicken

- Director:

- Joseph L. Mankiewicz

- Cast:

- Kirk Douglas, Henry Fonda, Hume Cronyn

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

Bad Company (1972) aka: In schlechter Gesellschaft

1h 29min1h 29min

1h 29min1h 29minBig Joe: My boy, let me give you a little piece of advice. If you're going to pull a gun on somebody, which happens from time to time in these parts, you better fire it about a half a second after you do it... because most men aren't as patient as I am.

- Director:

- Robert Benton

- Cast:

- Jeff Bridges, Barry Brown, Jim Davis

- Genre:

- Classics, Action & Adventure, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Kramer vs. Kramer (1979) aka: Kramer Versus Kramer

Play trailer1h 40minPlay trailer1h 40min

Play trailer1h 40minPlay trailer1h 40minTed Kramer: [as Billy brings ice cream to the table] You go right back and put that right back until you finish your dinner...I'm warning you, you take one bite out of that and you are in big trouble. Don't...Hey! Don't you dare...Don't you DARE do that. You hear me? Hold it right there! You put that ice cream in your mouth and you are in very, very, VERY big trouble. Don't you dare go anywhere beyond that...Put it down right now. I am not going to say it again. I am NOT going to say it AGAIN.

- Director:

- Robert Benton

- Cast:

- Dustin Hoffman, Meryl Streep, Jane Alexander

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Places in the Heart (1984) aka: Texas Project

1h 47min1h 47min

1h 47min1h 47minMr Will: Mrs. Spalding, can I ask you a question?

Edna Spalding: Yes.

Mr Will: What do you look like?

Edna Spalding: I have long hair and I tie it up in the back. And I have brown eyes. I always wanted to have blue eyes, like my Mama, but, Margaret got those. And my teeth stick out in front, a little, because I sucked my thumb a long time when I was a little girl. I'm no real beauty. I'm all right.

- Director:

- Robert Benton

- Cast:

- Sally Field, Lindsay Crouse, Ed Harris

- Genre:

- Children & Family, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Nadine (1987) aka: Nadine - Eine kugelsichere Liebe

1h 20min1h 20min

1h 20min1h 20minBuford Pope: Why is it you work your butt off all your entire life just to get ahead, and it takes a couple of nitwits about ten minutes to screw the whole thing up?

- Director:

- Robert Benton

- Cast:

- Jeff Bridges, Kim Basinger, Rip Torn

- Genre:

- Comedy, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Billy Bathgate (1991) aka: Tay Sai Đắc Lực

1h 42min1h 42min

1h 42min1h 42minBo Weinberg: Look at it this way Arthur, you're the one on the lam, and I'm the one on the town. Who would you rather be at this moment, you know what I mean?

- Director:

- Robert Benton

- Cast:

- Dustin Hoffman, Nicole Kidman, Loren Dean

- Genre:

- Drama, Thrillers, Classics, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

Twilight (1998) aka: Magic Hour

Play trailer1h 31minPlay trailer1h 31min

Play trailer1h 31minPlay trailer1h 31minCatherine Ames: Honestly, Harry. Did you see me in The Last Rebel?

Harry Ross: Yeah.

Catherine Ames: And you saw me in The End of Desire?

Harry Ross: Yeah.

Catherine Ames: Then I think you've seen everything there is of me to see.

Harry Ross: I also remember a movie your husband made. He shot 12 guys with a 6-shot revolver. I ain't gonna argue with that kind of marksmanship.

- Director:

- Robert Benton

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, Susan Sarandon, Gene Hackman

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

The Human Stain (2003) aka: La Piel Del Deseo

Play trailer1h 41minPlay trailer1h 41min

Play trailer1h 41minPlay trailer1h 41minColeman Silk: Cowards die many times before their death; the valiant only taste death but once. Of all the wonders that I yet have heard, it seems to me most strange that men should fear; seeing that death, a necessary end, will come when it will come.

- Director:

- Robert Benton

- Cast:

- Anthony Hopkins, Nicole Kidman, Ed Harris

- Genre:

- Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Feast of Love (2007) aka: Golpe de amor

Play trailer1h 32minPlay trailer1h 32min

Play trailer1h 32minPlay trailer1h 32minHarry Stevenson: There is a story about the Greek gods. They were bored, so they invented human beings, but they were still bored, so they invented love. Then they weren't bored any longer, so they decided to try love for themselves. And finally they invented laughter, so they could stand it.

- Director:

- Robert Benton

- Cast:

- Morgan Freeman, Radha Mitchell, Alexa Davalos

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-