As the BFI launches its latest season, Love. Sex. Religion. Death. The Complete Films of Terence Davies, Cinema Paradiso reflects on the career of one of Britain's finest film-makers.

Fate and finance conspired to prevent Terence Davies from making more than five shorts, eight features, and a documentary during his five-decade career. Nevertheless, his output is quite remarkable, not only for the personal insights it offers, but also for the aesthetic rigour that makes Davies's work so visually distinctive.

In 1988, he claimed, 'I make films to deal with my family history.' Yet he always considered himself to be an outsider. 'I don't feel part of life,' he once said. 'I always felt as though I was a spectator.' But, despite this sense of detachment, Davies always insisted that his films came from deep inside him. 'I can't do anything that I don't passionately believe in,' he declared. 'I can't see the frames.'

Amusingly, Davies was well aware of his limitations, once noting, 'if I did an action movie, it would be two cars going very slowly - that's not exciting!' But, while he knew where he stood, Davies often found himself at loggerheads with those who held the purse strings within the British film industry and despaired of their obsession with producing pictures that would play in America. 'The only thing we have a genius for in England now,' he sneered, 'is stupidity.'

In essence, Davies fashioned a 'cinema of reminiscence' that not only dwelt upon time and memory, but also family and trauma, religion and guilt, homosexuality and alienation, and the joy that music and cinema could bring before the encroachment of the shadow of death. Critic Michael Koresky has shrewdly observed that Davies devised a cinema of paradoxes 'between beauty and ugliness, the real and the artificial, progression and tradition, motion and stasis'. As much a one-man genre as an auteur, he stands alone in the annals of recent British cinema, still waiting to be fully appreciated.

The Family Circle

Terence Davies was born in the Kensington district of Liverpool on 10 November 1945. He was the youngest of the 10 children (seven of whom survived infancy) raised by working-class Catholic, Thomas Davies, and his wife, Helen (née O'Brien). Thomas was described by the Los Angeles Times in 1989 as 'a Liverpudlian odd-job specialist', although other sources have claimed he was a shipping clerk and a rag-and-bone man.

Terence was terrified of him, recalling 'I was just frightened of him all the time. He was so violent, so permanently enraged...He seemed to me anyway - thinking back on it, now - almost psychotic. Perhaps not mentally psychotic - but perhaps a psychosis of the soul. I don't know...Someone said in an review: he was a man driven mad by parenthood. Perhaps, because he had an awful life, it scarred him emotionally - and instead of saying, "Well, I'll make it better for my kids," his attitude was, "Well, I had it rough; there's no reason why you should have it easy."'

In the same profile, Davies recalled one of the many occasions (which took place before he was born) in which Thomas had gone into a black rage against Helen. 'She'd gone upstairs to the bedroom...He came after her. And she said, "I just felt that I couldn't take any more." So she opened the window when my father came - and she leaned out, with my brother (Kevin), only a baby, in her arms, and jumped. A soldier was walking past just then and caught them both!'

In fact, Davies became more sparing in the press about details of life in 18 Kensington Street. However, as we shall see, he drew heavily on his experiences for the films in 'The Terence Davies Trilogy' and his first two features. When Thomas died of cancer when Terence was seven, he could barely hide his relief. 'I remember how happy I was,' he told a reporter. 'Just for four years - from seven to 11- I was ecstatically happy and everything seemed magical. Literally, I was sick with happiness.' However, as he explained in another interview, 'I was conscious of being ecstatically happy but knowing it was going to go.'

Davies described a legacy of his father's reign of terror. 'The one thing I can't bear now is atmospheres,' he confided. 'I can come into a room full of people and I can tell you who's had [an argument]. I always say: if I've upset you, just come out with it. If you cold-shoulder me, I instantly see [my father] sitting in the corner of the parlour and I'm a seven-year-old again.'

By chance, the age at which Davies felt liberated from tyranny happened to coincide with the discovery of the passion that would shape his future. In 1953, his sister took him to see Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen's Singin' in the Rain (1952). 'During that scene in the rain,' he recalled in 1995, 'I cried and cried and cried.' His sister had asked, 'Why are you crying?' and he had replied, 'Because he looks so happy! Nothing does that for me like the old Hollywood musicals. I love Cries and Whispers, too, but it's hardly a toe-tapper, is it? I wish I could say I'd made something as great as Singin' in the Rain but alas, no, I haven't.'

As there were eight cinemas within walking distance of the Davies household, the young Terence became addicted. Indeed, it's telling how many of the films that he saw from this period made it into his Top 10 for Sight and Sound's decennial poll in 2012: Orson Welles's The Magnificent Ambersons (1942); David Lean's Great Expectations (1946); Max Ophüls's Letter From an Unknown Woman (1948); Robert Hamer's Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949); Frank Launder's The Happiest Days of Your Life (1950); Singin' in the Rain (1952); Gordon Douglas's Young At Heart (1954); Charles Laughton's The Night of the Hunter (1955); John Ford's The Searchers (1956); and Basil Dearden's Victim (1961).

It would seem as though Vincente Minnelli's Meet Me in St Louis (1944) just missed the cut, while Davies remained fond of Henry Koster's The Robe (1953), which was the first feature to be released in CinemaScope. But Davies's favourites were musicals, with those with an Americana theme being as popular as the more varied ventures undertaken by producer Arthur Freed's celebrated unit at MGM. Davies doesn't seem to have forgiven Hollywood for cutting back on musical production in the 1950s. But this had less to do with the advent of rock'n'roll than with the fact that American audiences had lost faith in the genre in an age of film noir and problem pictures and had come to crave alternative forms of escapism. Musicals were also expensive to produce in an age of cutbacks, while the once torrential supply of new shows from Broadway had also started to dry up. What's more, the successors to Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra, and Gene Kelly were not in the same league.

Davies adored the popular music of the 1950s, saying, 'It's poetry for the ordinary, and that American Songbook is unequalled throughout the world. The very best of it is as good as Schubert or Mahler, any of the great song cycles.' But the tunesmiths of Tin Pan Alley were no longer writing for musicals. They had their eyes on the singles chart and the playlists at the major radio stations. Famously, Davies would blame The Beatles for the cultural sea change and would proudly brandish his disdain for four contemporaries who shared his social background. But, as we shall see later, he may well have had another reason for being so ill-disposed towards John, Paul, George, and Ringo.

A poignant inclusion in Davies's Sight & Sound selection is the school comedy, The Happiest Days of Your Life, as his own schooldays were anything but cosy. Arriving at Sacred Heart Roman Catholic boys' school at the age of 11, Davies was targeted by bullies and was subjected to frequent beatings over the next four years. With the teachers refusing to intervene, Davies was left with little resort than to pray for deliverance, as he was a devout Catholic. But the prayers went unheard, as did those about the 11 year-old's growing dread that he might be gay. He had first experienced guilty pleasure while watching the wrestling at Liverpool Stadium on Saturday nights. But, with homosexuality still illegal in the UK and homophobic attitudes being rampant, Davies was forced to deal with the fear and shame that resulted from his arousal entirely by himself.

'I realised at 11 that I was gay,' he told Scope magazine. 'And being Catholic, that ruined my life. I decided I would be celibate. And I am and have been for a long time. My childhood was over in a second. That makes me full of regret. I just wanted to be ordinary and normal, with a car, two-and-a-half children, and a dog named Rover! It happened in the summer after leaving primary school. One day, these bricklayers were building a wall at the back of the house. It was hot so they just had jeans on. I looked out of the window and I thought, "I shouldn't be looking at another man like this." In an instant, my childhood ended. It was awful. I still can't go over it. I just wanted to be ordinary. I still do. I think everyone else has got the key to life and I haven't.'

When pressed by the interviewer as to whether he had ever been happy since the age of 11, Davies replied: 'No, never. I'm afraid not. You do feel a certain contentment and moments of true ecstasy. I get that from art, from the people I love, and people who love me: it's only a small number but I couldn't live without them. But happy, no, not in the way I was between 7 and 11. I cannot tell you how wonderful it was. To discover the world every single day, it was fabulous - better than sex!'

'Being gay has ruined my life,' Davies would later claim. 'I hate it. I'll go to the grave hating it.' He also averred, 'The seven years from 15 to 22 were awful, and I never ever want to go through anything like that again.' He broke out of the cycle by abandoning his faith, which he would thenceforth dismiss as a monstrous lie. However, it would take something equally radical to escape the drudgery of working as an unqualified accountant - after toiling for several years as a shipping office clerk. 'I was twelve years in a job I absolutely detested,' he reflected, 'you just felt you were dying by the centimetre. I saw a lot of people go under. In the offices I worked in, they hated every minute of it, and dread[ed] when they got to 65, being given a Teasmade in the boardroom.' In 1973, Davies left his beloved mother and headed south to study on a local government grant at Coventry Drama School.

Like the Corners of a Mind

Being sent to Coventry didn't suit Terence Davies. Fending for himself for the first time was fine, but the course proved frustratingly conventional. So, on hearing about the BFI Production Board on the radio, Davies submitted a script for a 40-minute short and was surprised to receive an £8500 grant to shoot it. Out of nowhere, he was a film-maker and he followed the monochrome Children (1976) by enrolling at the National Film School, where he made a follow-up short entitled, Madonna and Child (1980), for his graduation project.

Funded by the BFI and the Greater London Arts Association, Davies completed his story with Death and Transfiguration (1983) and did a tour of the festival circuit, where The Terence Davies Trilogy began to pick up awards. It would remain his only work set in the present day, for, as Davies explained, 'Being in the past makes me feel safe because I understand that world.'

In the first film, Robert Tucker (Philip Mawdsley) falls foul of the bullies at his Roman Catholic high school, where the teachers are little more than glorified thugs. His father (Nick Stringer) is equally brutal towards Robert's mother (Valerie Lilley), but the boy is still pained to see his father receiving an injection for the cancer that is slowly killing him. He is also stressed by witnessing his father receiving the last sacrament and is too frightened to watch the body being laid out.

At his father's funeral, Robert tries to support his mother. When friends and relations start to sing the old standard, 'Barbara Allen', the sense of loss hits home and Robert begins to cry. But, as we have seen in a series of cutaways showing Robert as a young man (Robin Hooper), his domestic situation hasn't been the only thing on his mind, as he has been trying to come to terms with the fact that he's gay and he shrugs at the end of a consultation with the doctor when he's asked if he's got a girlfriend yet.

Robert (Terry O'Sullivan) has reached his thirties by the start of the second film. At the end of each day holding down a dull clerical post, he takes the ferry across the Mersey to care for his mother (Sheila Raynor) in a small council flat. He has not told her that he is gay, but she still hears him sneaking out at night. On being refused admission to a club, Robert seeks company at a nearby public convenience.

Returning home one night, Robert notices a tattoo parlour and he calls the owner (or perhaps fantasises about doing so) and enquires about having his genitals tattooed. When he goes to confession at the parish church, Robert says nothing about his sex life. But he does endure a terrifying vision of dying and being brought before God to justify his actions.

The final film opens on Christmas Eve, with a dying Robert (Wilfrid Brambell) reflecting on his life. He remembers being told off as an eight year old (Iain Munro) by a nun for running on a corridor and attending his mother's funeral after having spent years caring for her. Images of muscle men compete for his attention with the recollection of playing an angel in a school play. But no amount of prayer would spare his mother and now Robert himself is on the verge of death.

A memory takes him back to a family Christmas, with relatives singing together and his mother hugging him. He recalls a carol concert and a nun asking if he loves God. But it's a kindly nurse who sits with Robert during his final hours. Trying to raise himself up to embrace his mother, he dies as the screen fills with white light.

Completed during three distinctive periods in Davies's life, the trilogy saw him gaining confidence as both a writer and a maker of images. Having never previously set foot on a film set, he had been convinced throughout the shooting of Children that the crew hated him and had nothing but scorn for his amateur efforts. However, the finesse with which he achieves his unique brand of 'memory-realism' is exceptional, as is the sophistication of his juxtaposition of sound and image. In Children, Davies uses the glass of the funeral hearse and the wood of the coffin to erase Robert and his mother from the shot, while the fevered conversation with the tattooist in Madonna and Child is illuminated with a tour of the Stations of the Cross at the parish church.

The funeral sequence at the start of

Death and Transfiguration is crosscut to 'It All Depends on You', which was a song that Doris Day had sung in Charles Vidor's Love Me or Leave Me (1955), which was a biopic about singer Ruth Etting's abusive relationship with racketeer Martin Snyder (James Cagney).

Not bad for someone who later admitted, 'I didn't know what I was doing. I just did it from what I felt was right.' But all the hallmarks of Davies's mature style are in evidence: the meticulous detail of the mise-en-scène; the methodically measured camerawork; the sense of melancholic beauty; an appreciation of off-screen space and parallel action; and a knack for matching music with a scene's emotional tone.

In a positive notice, Vincent Canby, the hard-to-please and often abrupt critic of The New York Times, opined that the Davies Trilogy 'makes Ingmar Bergman look like Jerry Lewis'. It's a fair point, as the vignettes can be tough going, in the manner of the films in The Bill Douglas Trilogy - My Childhood (1972), My Ain Folk (1973), and My Way Home (1978). But they announced the emergence of a bold and uncompromising talent.

Davies would return to Robert Tucker in his stream-of-consciousness novel, Hallelujah Now (1983), in which a greater emphasis was placed on the character's masochistic desires. But, while Davies was not quite prepared to leave Liverpool or abandon his autobiographical approach, he was very much ready to move into features.

Exceedingly Rare

There's an old saying that you can take the boy out of Liverpool, but you can't take Liverpool out of the boy. This was very much the case with Terence Davies, who once said of his birthplace: 'We love the place we hate, then hate the place we love. We leave the place we love, then spend a lifetime trying to regain it.' Three of his most important films were set in his native city and each is made in a completely different manner.

Although it turned out to be Davies's debut feature, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), was actually two shorts made two years apart. Combining 'memory-realism' and the 'poetry of the ordinary', the action turns around a Catholic Liverpudlian family to explore Davies's contention that the family is 'the source of everything that is wonderful and terrible in our lives'.

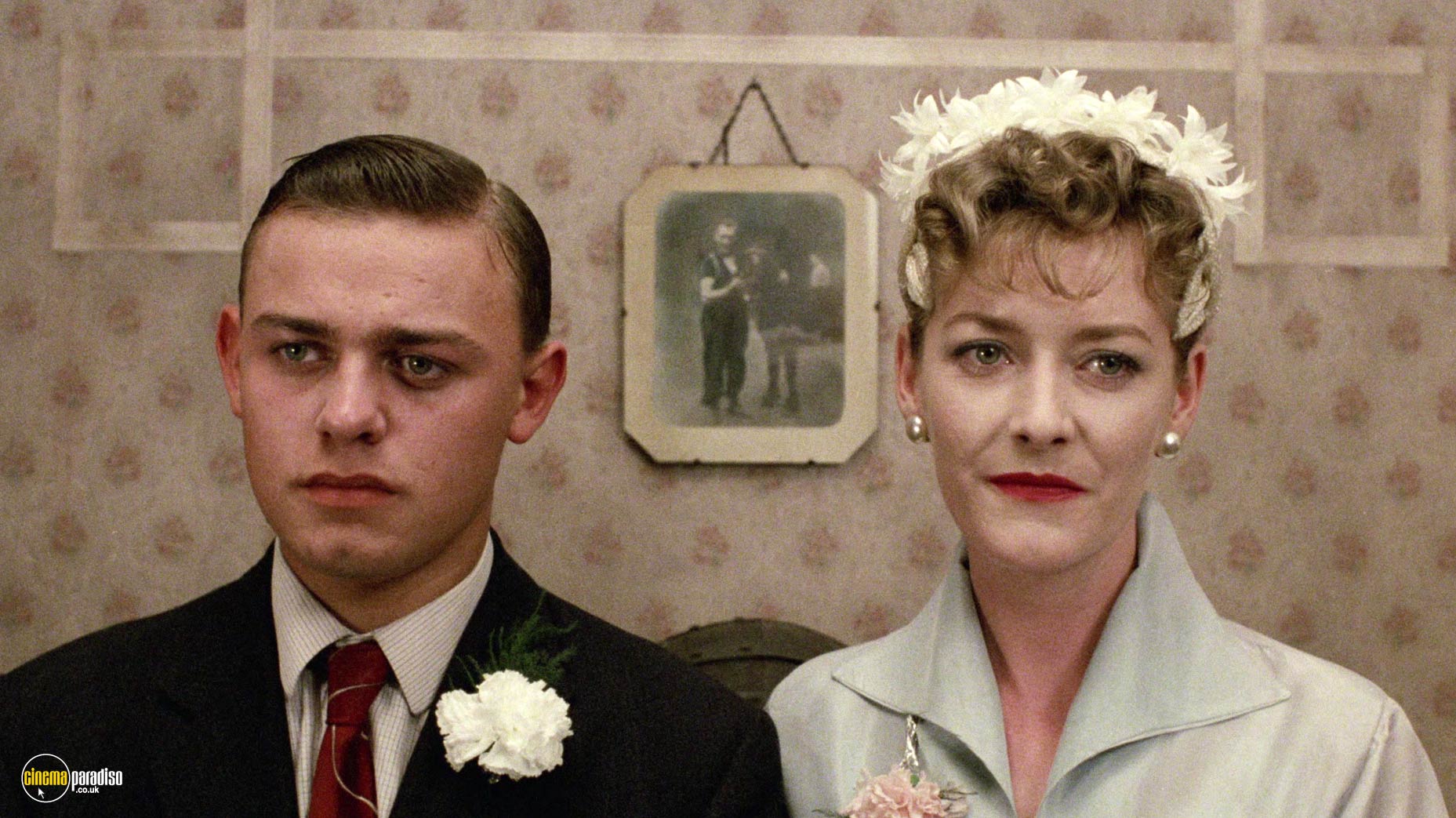

In the 'Distant Voices' section, siblings Eileen (Angela Walsh), Maisie (Lorraine Ashbourne), and Tony (Dean Williams) remember living with their tempestuous father (Pete Postlethwaite) and the hell he often made life for their docile mother (Freda Dowie). However, they also recall lighter moments, with both family and friends, and the music that was so central to everyday working-class life ('I remember not just what the fifties looked like, I remember what it felt like, and that's a different thing.'). In 'Still Lives', the clan gathers for a christening and later for a wedding, although the shadow of the past continues to impinge. Moreover, even though films like Henry King's Love Is a Many Splendored Thing (1955) provide a temporary escape, there is never any getting away from the harsh realities of existence.

Presented to resemble the way in which memories creep up on us, this deeply affecting film was made on a shoestring and employs sounds and images to evoke not only a time and place, but also the attitudes and personality traits that shaped family bonds and friendships. Memorably pulling away the table cloth from under a Christmas lunch, Pete Postlethwaite is exceptional as the hair-triggered father, while Freda Dowie exudes the mournful dignity of the battered wife who retains the memory of the dancing charmer with whom she had fallen in love. As Davies put it while reflecting upon the thorny nature of the average rite of passage, 'you don't want the family to change, but the family will change, and by the time those changes have taken place, the haven has becomes a prison, and you're too old to do anything about it'.

With its posed tableaux resembling faded snapshots, the film echoed T.S. Eliot's 'Four Quartets' in its intimacy and innovation. But the influence of Hollywood musicals and women's pictures, as well as postwar British cinema (including Ealing's non-comedies) can be detected in a boldly non-linear film that was much admired by Jean-Luc Godard, who usually had little time for pictures from across the Channel. Critic Derek Malcolm dubbed it 'a musical version of Coronation Street directed by Robert Bresson, with additional dialogue by Sigmund Freud and Tommy Handley'. This is a a shrewd assessment of Davies's style, as he eschewed nostalgia and kitchen sink cliché in seeking to show that the boy from Kensington had come up in the world and had obtained highbrow credentials to go with the proletarian roots, to which he paid subtle homage by using his own father's image for the picture on the parlour wall.

The winner of the International Critics Prize at Cannes, Distant Voices, Still Lives was unlike anything that British cinema had produced before. As critic Jonathan Rosenbaum would opine, 'years from now, when practically all the other new movies currently playing are long forgotten, it will be remembered and treasured as one of the greatest of all English films'. The challenge now was to follow it.

Davies did so by corralling more personal memories of a Liverpool childhood in the mid-1950s. Indeed, the central character of The Long Day Closes (1992) even shares Davies's youthful nickname, Bud. He's played by Leigh McCormack as a bit of a mummy's boy, as she provides him with a sanctuary from the indignities of school, where he is bullied by classmates and caned by teachers who would rather discipline than educate. However, much to the amusement of his older sister, Helen (Ayse Owen), the 11 year-old knows how to wheedle money out of his mother (Marjorie Yates) to go the pictures, with the local cinema rivalling the parish church for splendour and spectacle. But, while Bud edges inexorably towards the conclusion that Catholicism is a mendacious waste of his time, he never loses his faith in cinema or the consoling power of music, even when unwelcome emotions intrude. such as the sensations that Bud experiences while watching a shirtless bricklayer (Kirk McLaughlin) working near the house.

This is very much a film about observing the passing parade, as postwar children were expected to be seen and not heard. It recycles sobering elements from the Davies Trilogy, yet it also celebrates what the director considered to be the happiest time of his life. Filmed at Rotherhithe Studios, the meticulous recreation of a part of Liverpool that had disappeared during the 1961 redevelopment is complemented by a songtrack that reflects an era when the nation gathered around radios rather than television sets for its shared cultural moments. And Davies's bitterness at how this changed in the following decade is made abundantly clear in the final part of his Scouse odyssey, Of Time and the City (2008).

Marking a return to film-making after a lengthy fallow period, this archival documentary was much admired by critics, despite Sukhdev Sandhu branding it 'a relentlessly maudlin drool of clichés and sentiment'. It wasn't universally popular with audiences on Merseyside, either, with many feeling as though Davies had prioritised the personal over the communal experience of living in a port whose musical and sporting triumphs had provided relief from the grinding reality of economic decline, shifting socio-cultural structures, and the disdainful neglect of successive governments, including the ones presided over by the MP for Huyton.

Musing over monochrome clips from the archives, Davies explores how the Liverpool of his youth changed to the point where he became a stranger in his own backyard. 'I don't go up that often,' he admitted while promoting the film, 'because Liverpool is full of memories...I look around and think this is not the place I grew up in and loved.' He continued, 'Now I'm an alien in my own land...I couldn't go back to live there, I just couldn't.'

Amidst fond recollections of day trips to New Brighton, there is plenty of waspish criticism of the Britain in which Davies grew up. He hisses his disapproval of 'the Betty Windsor show' that started with the 1947 royal wedding that had made a mockery of the struggles that the rest of the country were enduring at a time of severe postwar austerity. Without revealing where his love of classical music came from, Davies also took aim at The Beatles, whom he dismissed as 'a firm of provincial solicitors', in spite of the fact that Merseybeat had done so much to raise the profile of the city and the spirits of its people.

Davies adored the Great American Songbook, but he was wrong to blame rock'n'roll for its decline. As we have seen, musicals were becoming prohibitively expensive to stage during a period of postwar cost-cutting and Hollywood focussed on major Broadway shows rather than commissioning new tunes from Tin Pan Alley. Thus, American songwriters started concentrating their efforts on recording artists and hoping to land album slots that might get a little radio airplay. A new generation of singers that included Peggy Lee and Nat King Cole also helped change public tastes alongside the new rock and blues artists.

Paul McCartney has always highlighted the importance of family sing-songs to his musical education and there's an element of inverted snobbery in Davies's refusal to acknowledge that he shared a common heritage with the Fab Four. 'Not only could we not afford Beatles music,' he told one reporter, 'but I absolutely detest pop music. It's agony to listen to, especially British pop music. Oh, God, kill me now - I'm ready to die after two minutes. I've never liked The Beatles. "Money can't buy me love." Oh, yeah, there's a big revelation. You can't imagine them writing a witty lyric. Look at Cole Porter. No one can write a Cole Porter song. No one can write a Lorenz Hart song. But then, music has changed. Popular music isn't aimed at people like me. After the rise of Elvis Presley and The Beatles, all my interest disappeared. I remember being taken by one of my sisters to see Jailhouse Rock (1957). I sat there riven with embarrassment. I thought, "Doesn't he look ridiculous?" And this awful voice. Had I been a spy, they'd only have to show me 20 minutes of that and I'd tell them anything.'

Ignoring the point that John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison all wrote witty lyrics and were feted by many of the singers Davies admired, he turned up his nose at The Beatles because he saw in the cocky quartet the very kids who had made his life a misery at school. Moreover, as he considered himself intellectually superior to the Mop Tops, he was envious of the fact that they seemed to have things handed to them while he had to fight even to get a short made. It's a great shame that he had such a block when it came to The Beatles, as Davies has more in common than he was prepared to acknowledge.

In 2010, Davies returned home for a last time for the BBC radio drama, Intensive Care, which returned to the theme of his relationship with his mother. Lennon and McCartney had each lost their mothers as teenagers. Perhaps someone needs to write a drama about Davies and McCartney meeting by chance and getting to the bottom of what bothered the director so much about the four lads from his own neck of the woods who had shaken the world when so few had seen his films.

Page and Stage

Although he was ready to spread his wings and make a film without a Scouse connection, Davies didn't stray too far from his previous preoccupations with The Neon Bible (1995), which was adapted from a novel that John Kennedy Toole had written when he was 16, only for it to go unpublished until 20 years after his death. Sadly, it's not currently available to Cinema Paradiso members, so we shall content ourselves to highlighting the similarities to The Long Day Closes and the story of David (Jacob Tierney), whose abusive father (Denis Leary) disappears during the Second World War, leaving him in the care of his put-upon mother (Diana Scarwid) and his spirited singer aunt, Mae (Gena Rowlands).

With the arrival of travelling preacher Bobbie Lee Taylor (Leo Burmester) giving him another opportunity to denounce organised religion, Davies was aware that he wasn't quite finding the soul of the text or the connections between Liverpool and 1940s Georgia. When the film disappointed commercially after drawing mixed reviews at Cannes, he conceded, 'It doesn't work, and that's entirely my fault.' But he insisted that he needed such a transitional piece to help his style mature. That said, he still found champions in the like of Jonathan Rosenbaum, who wrote, 'Davies doesn't offer a cinema of plot or a cinema of ideas, but a cinema of raw feelings and incandescent moments that wash over you like waves. You might find some of these waves boring if you assume that each one has to make a separate point to justify its existence.'

Proof that Davies had benefited from his experience came in the form of The House of Mirth (2000), which he adapted from a novel by Edith Wharton. Critics were quick to make comparisons with Martin Scorsese's The Age of Innocence (1993), but Davies captures the spirit of Gilded Era New York and Wharton's scathing and incisively civilised satire with considerable acuity on a much more modest budget.

At the heart of the story is Lily Bart (Gillian Anderson), who returns to Manhattan to live with her aunt (Eleanor Bron) and her younger cousin, Grace Stepney (Jodhi May). Accustomed to the finer things, Lily seeks to marry. But she realises that adored lawyer Lawrence Selden (Eric Stoltz) doesn't have the resources to keep her and is hurt when she acquires some letters that he had exchanged with the married Bertha Dorset (Laura Linney). Unable to take seriously the entreaties of Percy Gryce (Pearce Quigley) or the cynical suggestions of financier Simon Rosedale (Anthony LaPaglia), Lily allows herself to accept the assistance of Gus Trenor (Dan Aykroyd), the husband of her friend, Judy (Penny Downie). However, he has ulterior motives and, when Lily refuses to become his mistress, she finds herself $9000 in debt and her problems increase during an ill-fated trip to Europe that sees her become entangled with the feuding Dorsets.

Davies admitted he had known nothing about The X-Files (1993-2018) and had cast Anderson as Lily because she reminded him of a John Singer Sargent painting. In fact, she is highly impressive as the socialite falling victim to the lecherous chauvinism that prevailed in the upper echelons at the turn of the last century. The nouveaux riche milieu is superbly recreated by designer Don Taylor and photographed with a painterly feel for light and texture by Remi Adefarasin that made the film look very different from the heritage style that had been established by James Ivory and Ismail Merchant.

Yet audiences didn't respond to the sombre story or its tragic heroine. Consequently, Davies found it difficult to raise funds for his proposed adaptation of Lewis Grassic Gibbon's 1932 novel, Sunset Song. With the BBC, Channel 4 and the UK Film Council all passing on the project because it lacked 'legs', Davies had to accept the casting of Kirsten Dunst as his Scottish country lead before the plug was pulled. 'I did absolutely touch bottom,' Davies recalled later, 'I must say, and despair is awful because it's worse than any pain. You feel that all the decisions you made have been completely wrong. And one felt very disillusioned with oneself. I did despair, I have to say, and that was very hard. I really did think: it's all over now. I don't know how on earth I lived, I don't know how on earth I earned money. But it certainly puts iron in the soul. I just thought: "Oh well, that's it. If my career is over then The House of Mirth is not a bad note to end on."'

Few could have argued, as Davies had drawn on such Kenji Mizoguchi classics as Sisters of the Gion (1936), The Life of Oharu (1952), and Street of Shame (1955) to order to expose Lily's cruel treatment. But he had also woven in strands from films as different as Letter From an Unknown Woman, Douglas Sirk's All That Heaven Allows, Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing (both 1955), and Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974). No one in the British film industry of the time was displaying such cine-literacy, but it didn't help much when Davies tried to find backing for either the original romantic comedy, Mad About the Boy, or his adaptation of Ed McBain's hard-boiled crime novel, He Who Hesitates. In order to stay busy, he wrote and directed A Walk to the Paradise Garden (2001) for BBC Radio 3 and a two-part adaptation of Virginia Woolf's The Waves (2007) for Radio 4. Annoyingly, neither can currently be heard, while Auntie didn't consider Davies worthy of being cast away for Desert Island Discs.

In 2011, with Davies despairing of ever making another screen drama, the Rattigan Trust recruited him to mark the centenary of playwright Terence Rattigan by adapting the 1952 play, The Deep Blue Sea. This had previously been filmed by Anatole Litvak in 1955, with Vivien Leigh and Kenneth More, and it's baffling why one of Leigh's finest late performances is not available on disc. But Cinema Paradiso users might want to take another look at David Lean's Brief Encounter (1945), as its influence on Davies's interpretation is readily evident.

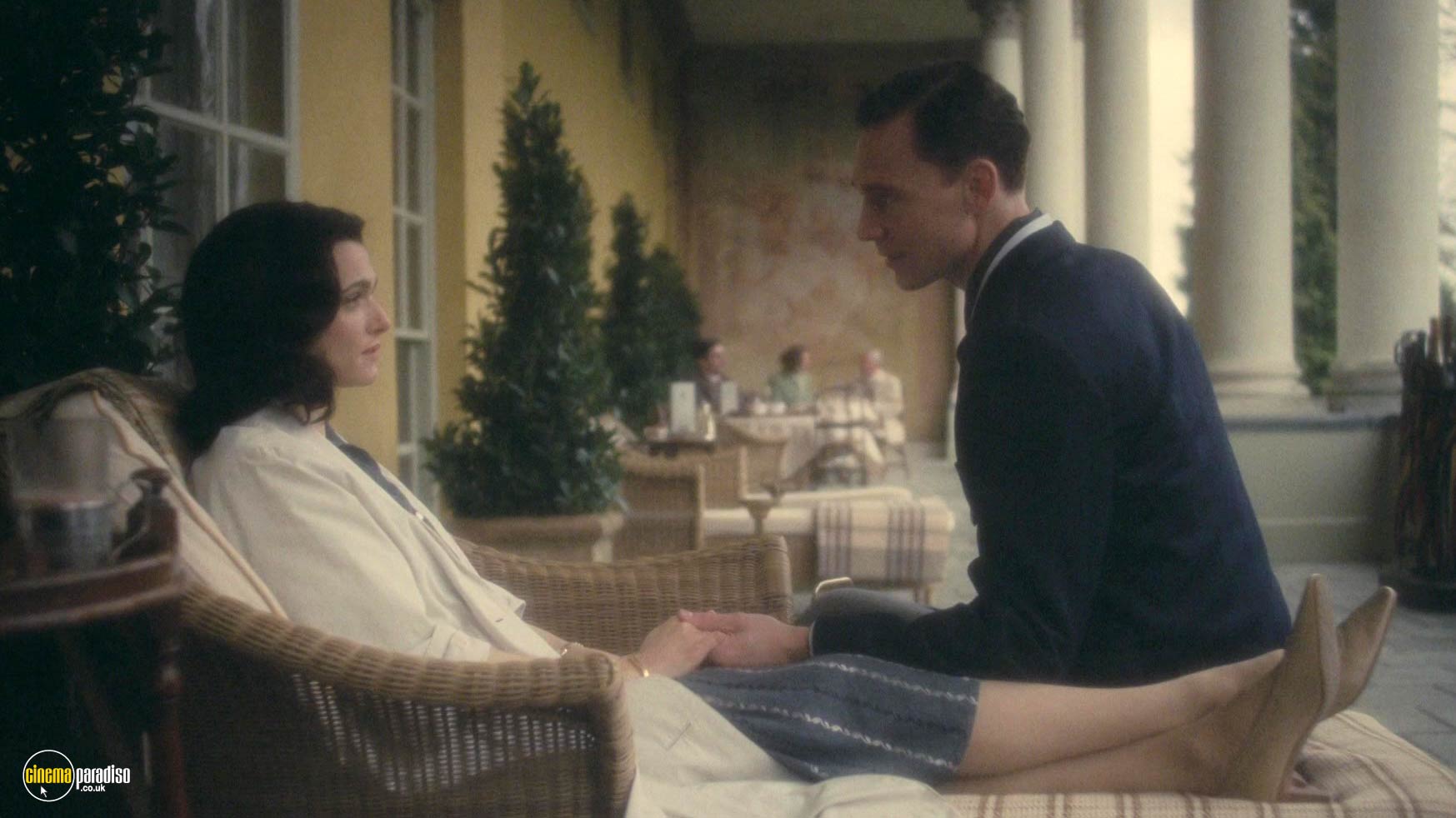

Hester (Rachel Weisz) is bored by her marriage to High Court judge, Sir William Collyer (Simon Russell Beale). However, she likes the trappings of her position and her refusal to settle for less prevents her from committing to an affair with RAF veteran, Freddie Page (Tom Hiddleston), who has embarked upon the fling to recapture the thrill he has been unable to replicate since returning to Civvy Street. Events come to a head when Hester decides to gas herself in the flat where she keeps her reckless assignations, as she can no longer bear an existence trapped between a regretted past and an uncertain future.

In addition to earning a Golden Globe nomination, Weisz was also named Best Actress by the New York Film Critics Circle. Yet, for all the accolades and acclaim, the film struggled to find an audience, as the combination of Rattigan's refined prose and Davies's studied visual poetry felt stiffly old-fashioned. There is an element of actorly deliberation, but this offers fascinating insights into Davies's approach to film-making and would make for a fine double bill with Neil Jordan's take on Graham Greene's The End of the Affair (1999), which also happened to be a remake of a 1955 original.

The critical enthusiasm for Davies's return to fiction resulted in him finally amassing the financing required to make Sunset Song (2015) - although he had also been exploring the possibilities of adapting Richard McCann's Mother of Sorrows. Set in Aberdeenshire in the years before the Great War, Lewis Grassic Gibbon's story echoes others in Davies's canon by dwelling on the violence of a tyrannical father. But this is also a treatise on female empowerment and the bond people forge with the land on which they live and work.

Raised by her parents (Peter Mullan and Daniele Nardini) on the Blawearie farm near the remote Highland village of Kinraddie, Chris Guthrie (Agyness Deyn) dreams of becoming a teacher. However, when her mother kills herself and the twins born as the result of a rape, Chris decides to help her brother, Will (Jack Greenlees), run the farm after father John suffers a debilitating stroke. Nevertheless, Will seizes his chance to establish a new life away from the farm, although not before he has introduced his sister to Ewan Tavendale (Kevin Guthrie), who seems the perfect husband until he is changed beyond all recognition by his experiences on the Western Front.

Packed with plot and brooding emotional intensity, this is a harrowing narrative that is filled with snatches of song that reflect Davies's acknowledged debt to Stanley Donen's Seven Brides For Seven Brothers (1954). However, in shooting in both 65mm and digital formats, cinematographer Michael McDonough also takes cues from the Danish artist, Vilhelm Hammershøi, in fashioning visuals that recall the way in which Terrence Malick recreates lost vistas. Despite effusive critical support, however, the audience proved modest and Davies remained British cinema's best kept secret. He was proud of finally realising this deeply personal project, however, revealing: 'It's about forgiveness and accepting what has happened, and not being bitter, which is what my mother did. These are the cards you are dealt, so you get on with it and don't complain. That I find enormously moving.'

Poets' Corner

A rush of creativity saw Davies complete his next feature before Sunset Song was released. However, he had been working on a biopic of American poet Emily Dickinson for some while and had decided to shoot the film in an exact replica of her Amherst home on a Belgian soundstage. Despite informing Cynthia Nixon that he found Sex and the City (1998-2004) to be 'pernicious', Davies had watched her performance as Miranda Hobbes with the sound down and had been impressed by the intelligence of her reaction shots. Clearly unfazed by such frankness, Nixon responded well to Davies's direction and she deserved greater recognition during awards season.

Feeling in places like a compressed Sunday serial, Davies's screenplay packs in plenty of incident to establish Emily's unconventional approach to life. The bulk of the action centres on the poet's later years, as Emily (Nixon) overcomes obstacles to having her work published, while she and sister Lavinia (Jennifer Ehle) deal with the problems of their ageing parents, Edward (Keith Carradine) and Emily (Joanna Bacon), and the struggles that new sister-in-law, Susan (Jodhi May), endures on marrying their brother, Austin (Duncan Duff), who has been prevented by his father from fighting in the Civil War.

With Emily becoming increasingly reclusive following the treacherous marriage of her friend, Vryling Wilder Buffum (Catherine Bailey), the scenario delves into such issues as familial duty, the status of women, and the painful nature of creativity. Yet, even though the focus falls very much on Dickinson, it's possible to detect the recurring themes of a queer film-maker who had spent much of his life being celibate because he had never fully come to terms with his own sexual identity. Indeed, he conceded to one interviewer, 'When Emily says, "I have many faults, there is much to rectify" - well, that's me.'

Once again, swooning reviews failed to translate into box-office success, while the excellent performances were again overlooked when it came to awards. And the same fate befell Davies's final feature, Benediction (2021), another project close to the director's heart, for, as he said while discussing this biopic of Great War poet, Siegfried Sassoon, 'Sassoon was looking for redemption. I was as well, until I realised that you can't find it if it's not in you.'

In the opening section of the film, the action centres around Sassoon (Jack London) and his friendship with fellow war poet, Wilfred Owen (Matthew Tennyson). In the 1920s, he becomes acquainted with celebrities like entertainer Ivor Novello (Jeremy Irvine), journalist Robbie Ross (Simon Russell Beale), and Bright Young Thing, Stephen Tennant (Calam Lynch), as well as such society stalwarts as Edith Sitwell (Lia Williams) and Lady Ottoline Morrel (Suzanne Bertish). The later stages deal with the married Sassoon (Peter Capaldi), his relationships with wife, Hester Gatty (Gemma Jones), and son, George (Richard Goulding), and his conversion to Catholicism.

Initially covering similar territory to Gillies MacKinnon's adaptation of Pat Barker's Regeneration (1997), this powerfully performed and immaculately staged insight into a tormented soul drew the usual warm praise in the press. However, the disappointing commercial showing hampered Davies in his efforts to raise funds for an adaptation of Stefan Zweig's posthumously published 1982 novel, The Post Office Girl. Instead, Davies had to content himself with making, But Why? (2021), a one-minute companion piece to Benediction commissioned by the Venice Film Festival; and Passing Time (2023), a three-minute paean to his adopted Essex landscape, in which Davies reads a poem that was accompanied by the music of Uruguayan composer, Florencia Di Concilio. Both can be found online.

Despite being diagnosed with cancer, Davies kept working and was adapting Firefly, Janette Jenkins's novel about the last five days of Noël Coward, when he died in Mistley on 7 October 2023. He was 77. When asked about his solitary existence, he had replied: 'I am celibate, although I think I would have been celibate even if I was straight because I'm not good-looking; why would anyone be interested in me? And nobody has been. Work was my substitute.'

He felt a little neglected by his peers. 'It would have been nice to be acknowledged by BAFTA,' he ruminated in a late interview. 'But they never have. Then again, there's also part of me that thinks: Isn't it just vanity? If a film lives every time it's seen, that's the real reward.'

Towards the end of his life, he had rather lost faith in modern cinema. When asked by Scope magazine about what he had seen recently, he confessed: 'I very rarely go now. I've lost my ability to disbelieve. And when you can call out the shots before they happen, you're not going on any journey. Oh, you're going to cut to a two-shot now - surprise, surprise, how fabulous. Or you hear a telephone ring and you cut to a telephone. Why can't you cut to an elephant and let the phone keep on ringing? And then the elephant says hello. Then it's interesting! Or better still, the elephant says, "It's for you!"

He continued, 'I still watch lots of musicals and British comedy of the late '40s and '50s. There are only two modern films I thought were wonderful: Laissez-passer (2002) by Bertrand Tavernier and Martin Scorsese's The Age of Innocence (1993). But there's nothing else in between. Most of the time, the curtains open and I think, "Ninety minutes? Life's too short and so am I."

Such self-deprecating humour helped Davies cope with the frustrations of a career that could have been as glorious as that of British cinema's other great maverick, Michael Powell. At a Q&A, he was once asked why his films were so slow and depressing. Without missing a beat, he replied, 'It's a gift.' A Scouser to the end, whether he liked it or not!