Cinema Paradiso's What to Watch Next series offers in-depth insights into the classics of world cinema, while also recommending related titles to discover and enjoy. This edition celebrates the 80th anniversay of one of the most audacious films ever made: Ernst Lubitsch's mocking comedy of Nazi barbarism, To Be or Not to Be (1942).

The United States had been dragged into the Second World War a matter of weeks before To Be or Not to Be (1942) was released into the nation's cinemas. Eighty years on, one can gauge the impact that a farce about Gestapo operations in Warsaw would have had on American audiences who had been watching from an Isolationist distance the calamities that had befallen Europe since September 1939.

To get an idea of how this provocative scenario would have been received at a time of national crisis, imagine a comedy about snipers being released in the aftermath of President John F. Kennedy's assassination or a romp about jihadi terrorists hitting screens in the days after 9/11. In order to understand the thinking behind this combustible masterpiece, we have to get to know its director, Ernst Lubitch.

From Slapstick Clown to Finesse

Born in Berlin in January 1892, Ernst Lubitsch was bitten by the acting bug at school and upset his draper father by sneaking away from the family shop at nights to perform in variety shows. In 1911, he joined Max Reinhardt's fabled Deutsches Theater and started supplementing the income from playing character parts by working as a handyman at the Bioscope film studio.

Within a year, Lubitsch started making short comedies and turned actor-director with Fräulein Seifenschaum (1914). In addition to creating slapstick gems like Shoe Shop Pinkus (1916), When Four Do the Same and The Merry Jail (both 1917). Lubitsch also perfected a Jewish everyman, who was seen to best advantage in Meyer From Berlin (1919).

Seen today, it's difficult to believe that the Meyer comedies were made by an artist who was considered 'a man of pure cinema' by Alfred Hitchcock, 'a giant' by Orson Welles and 'a prince' by François Truffaut. Heavily reliant on stereotypes, they could easily offend modern sensibilities. Yet they were hugely popular with German Jewish audiences, even though Lubitsch's shtick was broad in the extreme.

One man who didn't find Meyer's antics amusing, however, was Adolf Hitler, who became Chancellor in January 1933, just six weeks after Lubitsch had made what would prove to be his last visit to his home city. Such was Hitler's disdain for Lubitsch that he sanctioned the use of footage from this sojourn in Fritz Hippler's vile propaganda film, The Eternal Jew (1940), as part of a diatribe on the corrupting influence of Germany's Jewish population. For more on the way cinema was used to indoctrinate the masses, Cinema Paradiso users should order Rüdiger Suchsland's troubling documentary, Hitler's Hollywood (2017).

Back in the early days of the Weimar Republic, Lubitsch realised that his future lay behind the camera and he emerged as a major talent as Germany came to terms with defeat in the Great War. He had made over 20 films before he earned critical acclaim for a pair of Pola Negri dramas: The Eyes of the Mummy and Carmen (both 1918). But, having acted for the final time in Sumurun (1920), he discovered his métier for witty social satire with The Oyster Princess and The Doll (both 1919), which can be rented from Cinema Paradiso on high-quality DVD and Blu-ray as part of the six-film set, Lubitsch in Berlin, which also includes I Don't Want to Be a Man (1918) and Die Bergkatze (1921).

Lubitsch carried over his virtuoso visual wit into a trio of historical romps - Madame Du Barry (1919), Anna Boleyn (1920) and The Loves of Pharaoh (1921) - which resulted in 'the Griffith of Europe' receiving an invitation from Mary Pickford to direct her in Rosita (1923).

Despite finding America's Sweetheart a nightmare to work with, Lubitsch scored a critical success and signed a three-year contract with Warner Bros. Yet while he was afforded unprecedented creative freedom and reviewers started enthusing about his celebrated 'touch' following The Marriage Circle (1924), Lubitsch only enjoyed moderate box-office success with Forbidden Paradise (1924), Kiss Me Again, Lady Windermere's Fan (both 1925), and So This Is Paris (1926). Consequently, Warners allowed MGM and Paramount to buy out the remainder of his contract.

He charmed the critics again with The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (1927) and earned an Academy Award nomination for The Patriot (1928), which marked the last of his seven collaborations with Emil Jannings, who had just won the inaugural Oscar for Best Actor for his work in Victor Fleming's long-lost The Way of All Flesh (1927) and Josef von Sternberg's The Last Command (1928). But, even though directors across Hollywood were trying to emulate 'the touch', the embarrassing failure of the romantic melodrama, Eternal Love (1929), led some to wonder, as the talkies started to capture the public imagination, whether Lubitsch's patented brand of laconically urbane entertainment had come to seem a little old fashioned.

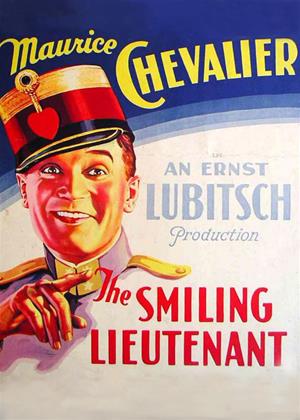

Lubitsch's silents had always exhibited a kind of musicality and it seemed inevitable that he should turn his hand to musicals following the introduction of sound in 1927. In The Love Parade (1929), however, he refused to follow the rubric of slotting songs into convenient places in the narrative by making them an integral part of the action. He also made innovative use of recitative to form bridges between the dialogue and the lyrics. Having earned his second Oscar nomination for this droll Ruritanian teaming of Jeanette MacDonald and Maurice Chevalier, he reinforced his reputation as the maestro of the new genre by directing MacDonald in Monte Carlo (1930) and Chevalier in The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), which marked his first collaboration with screenwriter Samuel Raphaelson, who had been partially responsible for the talkie boom, as his short story, 'The Day of Atonement', had been adapted for the big screen as Alan Crosland's The Jazz Singer (1927), in which Al Jolson had changed the nature of an entire medium with the improvised line, 'Wait a minute. Wait a minute. You ain't heard nothing yet!'

Making the Touch Talk

As cinema attendances dropped during the Great Depression, the Hollywood studios were forced to slash budgets and salaries in the face of plummeting profits. Following the failure of a rare venture into melodrama with The Man I Killed (1932), Lubitsch found himself under pressure at Paramount and agreed to combine his directing duties with the role of production chief.

No other film-maker of Lubitsch's calibre took on such an administrative role during the Golden Age of Hollywood. Having produced the portmanteau comedy, If I Had a Million, he signed up for a similar role on George Cukor's One Night With You (both 1932). This saucy musical reunited Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald. But Lubitsch was so dismayed by Cukor's leaden direction of his two favourite stars that he took over on the third day of shooting.

Following their triumphant collaboration with Herbert Marshall and Kay Francis on Trouble in Paradise (1932), Miriam Hopkins and Lubitsch reunited on his adaptation of Noël Coward's Design for Living (1933), which co-starred Gary Cooper and Fredric March. However, the arrival of Joseph I. Breen at the Production Code Administration in 1934 saw a stricter enforcement of the rules governing screen content and Lubitsch took a sabbatical from directing after his final teaming with Jeanette MacDonald on The Merry Widow (1934). Devoting himself to backstage duties at Paramount, he tried to work out how to adapt his effervescently sophisticated style to the new circumstances.

The fact that he followed his comeback picture, Angel (1937), with such peerless comedies as Bluebeard's Eighth Wife (1938), Ninotchka (1939), The Shop Around the Corner (1940) and To Be or Not to Be confirms that he found a way. However, he misfired with That Uncertain Feeling (1941) and slowed down considerably after completing Heaven Can Wait (1943). Illness forced him to pass A Royal Scandal (1945) to Otto Preminger before he returned to form with the sadly undervalued Cluny Brown (1946).

Tragically, at the age of just 55, Lubitsch suffered a fatal heart attack while shooting That Lady in Ermine (1948), which was again passed to Preminger to complete. It's entirely true to say that Hollywood has never seen his like again. Critic Dwight McDonald proclaimed his technique to be 'as close to perfection as anything I have ever seen in the movies'. But nothing can top François Truffaut's assessment: 'In the Lubitsch Swiss cheese each hole winks.'

Meanwhile, Back At the Teatr Polski...

A production of a new play entitled Gestapo is being rehearsed in the last days of August 1939. Producer Dobosh (Charles Halton) is furious with bit player Bronski (Tom Dugan) for trying to get a laugh by entering as Adolf Hitler and concluding a flurry of obsequious salutes with the line, 'Heil myself'. Fellow spear-carrier Greenberg (Felix Bressart) thinks the gag is funny. But the pompous Rawitch (Lionel Atwill) is impatient that the bickering is delaying his big scene. They all soon have more to worry about, however, when the Polish authorities cancel the production in case it provokes the bellicose Führer.

Star actor Joseph Tura (Jack Benny) and his glamorous wife, Maria (Carole Lombard), agree to continue with their run of Hamlet. However, Tura is disconcerted when dashing airman Stanislaw Sobinski (Robert Stack) leaves his seat on the second row at the start of his 'To Be or Not to Be' soliloquy. What he doesn't know is that Sobinski has slipped backstage to see Maria in her dressing-room. But he is too vain to believe that his wife would ever cheat on him with a younger man.

When war does break out, Sobinski flies to Britain to join the exiled Polish air force. However, he becomes suspicious when Professor Siletsky (Stanley Ridges) offers to take messages to the unit's loved ones and he secures permission to return to Warsaw to eliminate the professor before he can hand the list to the city's Gestapo chief, Colonel Ehrhardt (Sig Ruman).

As Sobinski is being watched, he persuades Maria to pass Siletsky's details to the underground. However, she discovers that the professor has arranged to meet Ehrhardt earlier than planned and Tura has to pose as 'Concentration Camp Ehrhardt' in order to get hold of the list. Initially unaware that he has arrived at the disguised Teatr Polski instead of Gestapo headquarters, Siletsky becomes suspicious that Ehrhardt is an imposter because he is too reliant on a script to improvise. When the traitor is killed during a backstage chase, however, Tura has to impersonate him in order to meet Ehrhardt and rescue Maria from Siletsky's room in the Gestapo stronghold. And that's when things start to get complicated!

The Imbecility of Evil

While President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sympathetic to Britain and its beleaguered continental neighbours, Isolationism remained official US governent policy during the first 27 months of the Second World War. Consequently, Hollywood's moguls were wary of commenting directly upon the situation in Europe, if only because they risked losing their lucrative markets. However, emigré directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Charlie Chaplin had already done their bit for the war effort back home with Foreign Correspondent and The Great Dictator (both 1940).

The latter exploited the fact that Chaplin's Little Tramp bore a resemblance to the Führer (here called Adenoid Hynkel) and Lubitsch borrowed the gag in an early exchange in To Be or Not to Be in order to ridicule Hitler as 'just a man with a little moustache'. He further demeans him by giving the role in Gestapo to Bronski, a bit player who insists on proving how much he resembles Hitler by strolling along a Warsaw street in full uniform. Indeed, Lubitsch even mocks his vegetarianism by having Bronski browse in a delicatessen window, while the narrator snarkily notes that Hitler has been known to swallow entire countries whole.

Such wisecracks were typical of the screenplay on which Lubitsch worked with Edwin Justus Mayer, after having drafted the story outline with Melchior Lengyel (who had earned an Oscar nomination for the storyline of Ninotchka). His intention was to show that, for every ruthlessly smooth operator like Siletsky, there was a bungling boob like Ehrhardt, who has been promoted so far out of his competency zone that he spends as much time dreading that his shortcomings will be rumbled as he does terrorising the citizens he is supposed to be oppressing.

The Nazi machine might well have swept across Europe in the opening months of the war, but Lubitsch was keen to expose the massed ranks of the mediocre underlings who had been entrusted with executing the orders of the evil elite. Given the state of the war in November 1941, it was an incredibly bold gambit. As a Berliner (albeit one who had been Stateside for almost two decades), Lubitsch would have been familiar with the character of his compatriots and their capacity for responding to tyranny. But one is left to speculate about how well informed he was about what was actually going on in the Third Reich and subjugated states like Poland.

When Walter Wanger demurred, Lubitsch found a willing ally for his satire in Alexander Korda, the Hungarian-born, London-based producer who was in Hollywood to co-ordinate features that could not only boost Home Front morale, but which could also inform American audiences about the grim realities facing Europe, from which they had been largely insulated since the US had opted out of the League of Nations. It has been suggested that Korda was acting as an agent for his close friend, Winston Churchill, with whom he had developed some film ideas during the 1930s. But, whether he earned his knighthood as a cineaste or a spy, Korda recognised the validity of Lubitsch's project and set up an independent production company through which to liaise with United Artists.

He also hired brother Zoltan Korda as production designer and his sets helped reinforce the conceit that the Nazi occupation had its garisly theatrical aspects. Moreover, he and exiled Polish cinematographer Rudolph Maté also made telling contrast between the grandeur of the hotel being used for the Gestapo headquarters and the rubble of the charming family businesses that had decorated the opening sequence.

Maté clearly took no offence at the way in which Lubitsch was presenting his homeland. But regular writing partner Samuel Raphaelson felt the premise was in poor taste ('I didn't have it in me to make gags about the Nazis in 1941.') and Lubitsch recruited Edwin Justus Mayer, who was better known as a playwright than a screenwriter. This meant, however, that he had an insight into the dynamics of the Tura household and the Teatr Polski troupe, while it also made it easier for Lubitsch to put his own stamp on the screenplay, as was his wont.

While working on the script, Lubitsch had considered Miriam Hopkins to play Maria. However, she quibbled about the number of lines she would have and was sidelined after she badgered the director about shifting the story focus on to Maria. She was replaced by Carole Lombard, whose career had been rescued during the silent era by slapstick king Mack Sennett after she had been left requiring plastic surgery to her face following a car crash.

Although she had frequently teamed with the genial Fred MacMurray in comedies and dramas alike, Lombard found her métier in screwball farces like Howard Hawks's Twentieth Century (1934), Gregory LaCava's My Man Godfrey (1936) and William A. Wellman's Nothing Sacred (1937). She had received an Oscar nomination for Best Actress for the middle feature, in which she had co-starred with ex-husband William Powell. However, current spouse Clark Gable disliked both Lubitsch and To Be or Not to Be and felt that Lombard should concentrate on less contentious fare like Alfred Hitchcock's Mr & Mrs Smith (1941).

Having enjoyed his previous collaborations with Maurice Chevalier, Lubitsch had briefly considered the Frenchman for the part of Joseph Tura. However, he saw a link between 'that great, great Polish actor' and Jack Benny, a onetime aspiring violinist who had found fame in vaudeville before forging radio partnerships with wife Mary Livingstone and African-American comic, Eddie 'Rochester' Anderson. Sadly, the four films they made together in the 1930s are unavailable on disc in this country. But Cinema Paradiso users can catch their reunion in Robert Aldrich's road movie, It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963).

Benny's public persona was predicated on his fabled miserliness, but Lubitsch channelled this into a vanity that convinces Tura that he can get away with impersonating both a top-ranking traitor and a Gestapo colonel. However, Tura's bravado masks an insecurity that causes him to bridle when handsome young airmen keep leaving their seats as soon as he utters the opening line of Hamlet's famous disquitation on the value of life.

For all the excellence of Lombard and Benny, the performances of the supporting cast are also exceptional. Lubitsch believed that in order 'to play comedy you had to have a circus inside you', and he found some peerless clowns to help him ridicule the Reich.

Having been driven from both Germany and Austria by the Nazis, Jewish actor Felix Bressart found a warm welcome in Hollywood from his fellow expats. Henry Koster cast him in the Deanna Durbin musical, Three Smart Girls Grow Up, before he demonstrated his comic mastery as Buljanoff opposite Greta Garbo in Ninotchka (both 1939). He reunited with Lubitsch on The Shop Around the Corner prior to giving three moving renditions of Shylock's 'Hath not a Jew eyes?' speech from William Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice. Cinema Paradiso users can also see Bressart in the multi-directored Ziegfeld Girl (1941), Richard Thorpe's Above Suspicion (1942) and William Dieterle's Portrait of Jennie (1948).

Dublin-born Tom Dugan was raised in Philadelphia and learned his trade in minstrel shows and vaudeville before reaching Broadway. A prolific bit-part player, he racked up around 270 credits, including a scene-stealing moment as a sentimental cop in Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen's On the Town (1949). He also amused as No Thumbs Charlie in Sidney Lanfield's The Lemon Drop Kid (1951). But he never found another role to match the self-heiling Bronski.

The haughty Rawitch (who has a good kosher joke before trying to steal a scene by bigging up his part as an SS officer) proved to be one of the last worthwhile roles offered to Croydon-born Lionel Atwill. He had followed decades on stage with a string of early sound horrors. including Michael Curtiz's The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933). Atwill also became part of the Universal stock company after playing one-armed Inspector Krogh in Rowland V. Lee's Son of Frankenstein (1939).

But he gave his most impressive performance as Don Pasqual Costelar opposite Marlene Dietrich in Josef von Sternberg's The Devil Is a Woman (1935), although he also proved a fine foil for Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce, as Dr Mortimer in Sidney Lanfield's The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939) and as Professor Moriarty in Roy William Neill's Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (1942). By the time of the latter's release, however, Atwill's reputation had been tarnished by a perjury charge following an orgy at his home.

The characters played by Charles Halton would have thoroughly disapproved of such sordid behaviour. A veteran of some 180 films, he invariably played petty types like Dobosh, who insist they know best, even when they're wrong. With his round glasses and pinched expression, Halton didn't always make it into the onscreen credits, but he will always be remembered as Carter the bank official in Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1946).

Talkies came too late for Southampton-born Stanley Ridges to play the romantic leads that had earned him a niche on Broadway. But he proved a versatile character actor, notably holding his own against Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi in playing a genial academic whose darker side emerges after a life-saving operation in Arthur Lubin's Black Friday (1940). Having played Professor Siletsky, Ridges switched sides to eradicate Nazi elements from Belgium in Herbert J. Biberman's The Master Race (1944).

Greater things awaited Robert Stack, who was at the start of his career when he was cast as the dashing pilot who gets itchy feet whenever Hamlet gets introspective. He had made his name by giving Deanna Durbin her first kiss in Henry Koster's First Love (1939), but admitted being terrified at landing such a key role in a Lubitsch picture. Family friend Carole Lombard held his hand and gave him tips on screen acting that helped him land a Best Supporting Actor nomination for Douglas Sirk's Written on the Wind (1956) and an Emmy for his work as Eliot Ness in the hit TV series, The Untouchables (1959-63). In later years, Stack focussed on comedy, notably sending up his own heroic persona in Steven Spielberg's wartime romp, 1941 (1979).

While Sobinski appears to be the only competent man in uniform in To Be or Not to Be, spare a thought for poor old Schultz, who is forever being blamed for the failings of his superior. He was played by Henry Victor, a Londoner who had been raised in the Kaiser's empire and had retained a Teutonic accent. This became problematic when the silent stalwart sought to move into talkies. But, while he made a mark as Hercules the strongman in Tod Browning's Freaks (1932), Victor became typecast as sinister Nazis, which makes Lubitsch's casting all the more inspired.

The same was true of Sig Ruman, a Hamburger who had fought in the Great War before becoming an actor. Based Stateside from 1924, he became a favourite stooge of the Marx Brothers in Sam Wood's A Night At the Opera (1935) and A Day At the Races (1937) and Archie Mayo's A Night in Casablanca (1946). Yet, while he could play comic Russians as well as Germans (see Ninotchka), Ruman had a sinister streak that was exploited in numerous wartime propaganda pictures (too few of which are available on disc in the UK). But Billy Wilder allowed him to be more sympathetic, as the amiable POW camp guard, Schulz, in Stalag 17 (1953).

A Laugh Is Not to Be Sneezed At

Shooting commenced on 6 November 1941, but got off to an uncertain start, as Jack Benny was so in awe of Lubitsch (whom he considered 'the greatest comedy director that ever lived') that he convinced himself that he could never attain his standards. Despite forcing Benny to endure 30 takes of the scene in which Tura finds Sobinski sleeping in his bed, Lubitsch used counter-psychology to boost his confidence by telling Benny that he was already a brilliant actor because he had managed to concoct a hilarious comic persona who was beloved by millions without being naturally funny himself.

Lubitsch also treated Benny to an in-joke, as one of the gravestones in the bombed-out cemetery is engraved 'Benjamin Kubelsky', which was Benny's real name. Not everyone found the scenes of Warsaw under the jackboot amusing, however, as a woman visiting the set had recently fled Poland and she fainted on seeing Nazi uniforms on the soundstage street.

Even though the US entered the war during the shoot, the atmosphere on set was mostly convivial. Lubitsch enjoyed flirting with Lombard, who was so enthralled by his way of directing that she reported to the studio on her days off to watch him work. She also enjoyed teasing Robert Stack, whom she and Gable had known since he was an adolescent.

Although the production wrapped on 23 December, Lombard was recalled on New Year's Eve for a photo shoot with Robert Coburn. Sadly, it would prove to be her final assignment, as she was killed in a plane crash on 16 January 1942, while on a war bond tour. She had raised more than $2 million and had decided to fly back from Indiana because she was due to appear on Benny's radio programme. As a result of her loss, Lubitsch cut Maria's coquettish line, 'What can happen in a plane?'

Costing $1,022,000, the film was doomed to make a loss on its initial release, from a combination of audiences shying away from seeing both the much-lamented Lombard playing for laughs and a farce about a once-distant conflict that had suddenly come closer to home. The condemnation of influential critics like Bosley Crowther of the New York Times also turned people against the picture. 'To say it is callous and macabre is understating the case,' Crowther sniffed, while the Motion Picture Herald grumbled that 'this treats humorously of the Nazis at a time when the war news is not funny'.

Many critics singled out the line about Tura: 'What he did to Shakespeare, we are now doing to Poland.' Lubitsch's wife hated the crack and after a test screening, friends like Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett implored him to remove it. But the Producttion Code Office found nothing against it and it stayed put, along with the comparison of Hitler to a piece of cheese and Ehrhardt's joke about the Polish concentration camps, in which the Germans did the concentrating while the Poles did the camping.

Variety was more upbeat in claiming this 'typically Lubitsch' outing was 'one of his best productions in a number of years'. But Lubitsch felt compelled to answer his critics in a New York Times article on 29 March, in which he stated that he 'was tired of the two established, recognised recipes: drama with comedy relief and comedy with dramatic relief. I had made up my mind to make a picture with no attempt to relieve anybody of anything at any time.'

In a second riposte to a scurrilous accusation that, as a German, he had delighted in the destruction of Warsaw, he confirmed, 'What I have satirised in this picture are the Nazis and their ridiculous ideology.' More importantly, Lubitsch had shown that the Nazis were anything but the Master Race. They were mere mortals, albeit with the capacity to be monsters, and the screenplay deftly highlights this by juxtaposing moments of wickedness and witticism. Tellingly, the only unfunny character is Professor Siletsky, the turncoat who assures Maria, 'In the final analysis, all we're trying to do is create a happy world.' Such is his lecherous attitude towards her, however, that he comes across as more of a creep than a quisling.

Lubitsch was also eager to use the theatrical setting to expose the way in which the Nazis had turned politics into show business, with their uniforms and rallies adding to the sense of choreographed spectacle. He also stressed how the members of the Teatr Polski are able to overcome their egotism and petty rivalries to rally round in order to pull off the performance of a lifetime in showing the Nazis to be ordinary people who were just as capable of bungling as they were of brutalising.

Jack Benny's father was so appalled by the sight of his son in a Gestapo uniform that he walked out of the theatre. But, once the film's rationale had been explained to him, he supposedly saw it 46 more times and became as big a fan of Lubitsch as his son. After all, as Greenberg tells Dobosh, 'a laugh is not to be sneezed at'.

You have to smile at the fact that Werner Heymann earned an Oscar nomination after taking on the task of scoring the film from the disapproving Miklós Rosza. He was also cited for another Alexander Korda release, Jungle Book (1942), which was directed by his brother, Zoltan. It's also worth a chuckle to realise that Lubitsch had beaten the Hollywood system to prove that grave matters could be satirised in order to make them comprehensible and manageable. And, in the process, had he introduced cinema to the art of black comedy. No wonder when fellow director Mervyn LeRoy presented Lubitsch with an honorary Academy Award in 1947, he lauded his 'adult mind' and his 'hatred of saying things the obvious way'.

-

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

1h 23min1h 23min

1h 23min1h 23minNowhere is the fabled 'Lubitsch touch' more readily evident than in this deliciously sly romantic comedy. Switching from Venice to Paris, the action centres on the machinations of thieves Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins as they fleece perfume heiress Kay Francis. Yet, for all the finesse of the performances, it's Lubitsch's visual wit that makes this such a delight, as he not only mocks the manners and mores of the elite, but he also plays fast and loose with the restrictions imposed by the Production Code.

- Director:

- Ernst Lubitsch

- Cast:

- Miriam Hopkins, Kay Francis, Herbert Marshall

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

That Night in Rio (1941) aka: Road to Rio

1h 27min1h 27min

1h 27min1h 27minDon Ameche and Alice Faye teamed for the sixth and final time in this Irving Cummings musical based on Rudolf Lothar and Hans Adler's play, The Red Cat. Impersonation is crucial to the plot, as American entertainer Larry Martin stands in for Baron Manuel Duarte while he tries to save his struggling airline. Unfortunately, the baron's wife and Martin's girlfriend (respectively played by Faye and Carmen Miranda) don't always know who they're talking to. Harry Warren and Mack Gordon's songscore adds to the fun.

- Director:

- Irving Cummings

- Cast:

- Alice Faye, Don Ameche, Carmen Miranda

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Music & Musicals, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Hangmen Also Die! (1943) aka: Trust the People / Never Surrender

Play trailer2h 15minPlay trailer2h 15min

Play trailer2h 15minPlay trailer2h 15minLubitsch's fellow exile, Fritz Lang, has no qualms in exposing the evil of the Nazi hierarchy in a story that was co-written by playwright Bertolt Brecht (his sole Hollywood credit) and centres on the crimes of Reinhard Heydrich, the Reichsprotektor of occupied Prague, who is played with malevolent menace by Hans Heinrich von Twardowski. As the true facts were still shrouded, the film credits Heydrich's assassination to the Czechoslovakian resistance. But it retains its potency and offers fascinating insights into the workings of wartime propaganda.

- Director:

- Fritz Lang

- Cast:

- Brian Donlevy, Walter Brennan, Anna Lee

- Genre:

- Drama, Thrillers, Classics, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

Andrzej Wajda: Canal (1957)

1h 32min1h 32min

1h 32min1h 32minThe middle part of the Andrzej Wajda war trilogy that also included A Generation (1954) and Ashes and Diamonds (1958), this tribute to the resistance mounted in the Polish capital's sewer system during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising follows the increasingly desperate efforts of various partisans to evade the pursuing Nazis. Roman Polanski would return to the ghetto in the Oscar-winning memoir of Wladyslaw Szpilman (Adrien Brody), The Pianist (2002), while Agnieszka Holland returned to the tunnel theme in the Oscar-nominated drama, In Darkness (2011).

- Director:

- Andrzrej Wajda

- Cast:

- Tadeusz Lomnicki, Urszula Modrzynska, Tadeusz Janczar

- Genre:

- Drama, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

The Last Metro (1980) aka: Le Dernier Métro

Play trailer2h 7minPlay trailer2h 7min

Play trailer2h 7minPlay trailer2h 7minAlthough François Truffaut was very much a man of the screen, he also loved the stage and his affection for actors shines through in this poignant reflection of Paris in 1942. While her Jewish husband hides in the basement of his Montmartre theatre, Marion Steiner (Catherine Deneuve) plans his escape while rehearsing a new play and dealing with the amorous attentions of her co-star, undercover Maquis agent Bernard Granger (Gérard Depardieu). With Jean-Louis Richard excelling as a collaborating critic, this paean to the ensemble spirit deservedly won 10 Césars.

- Director:

- François Truffaut

- Cast:

- Catherine Deneuve, Gérard Depardieu, Jean Poiret

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

To Be or Not to Be (1983) aka: Soy o no soy

1h 42min1h 42min

1h 42min1h 42minDividing the critics as much as the original, Alan Johnson's remake caused disquiet because it seemed harder to make jokes about the the truths that Lubitsch hadn't known about in 1942. But Mel Brooks and Anne Bancroft surrounded themselves with exceptional Jewish performers in their determination to continue defying Fascism. The roles of Tura and Bronksi are combined to give Brooks the bulk of the best gags. Charles Durning earned an Oscar nomination for his turn as Colonel Ehrhardt, who is much more buffonish than his predecessor.

- Director:

- Alan Johnson

- Cast:

- Mel Brooks, Anne Bancroft, Ronny Graham

- Genre:

- Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

The Producers (2005) aka: Los productores

Play trailer2h 9minPlay trailer2h 9min

Play trailer2h 9minPlay trailer2h 9minIn 1967, Mel Brooks won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay with a directorial debut that centred on a Broadway producer seeking to score a resounding flop with Springtime For Hitler, a musical about the Third Reich. Four years after Brooks and Thomas Meehan triumphed with a musical version of The Producers, Susan Stroman brought the show to the screen with Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick in the roles of Max Bialystock and Leopold Bloom that had originally been taken by Zero Mostel and Gene Wilder.

- Director:

- Susan Stroman

- Cast:

- Mel Brooks, Nathan Lane, Matthew Broderick

- Genre:

- Comedy, Music & Musicals

- Formats:

-

-

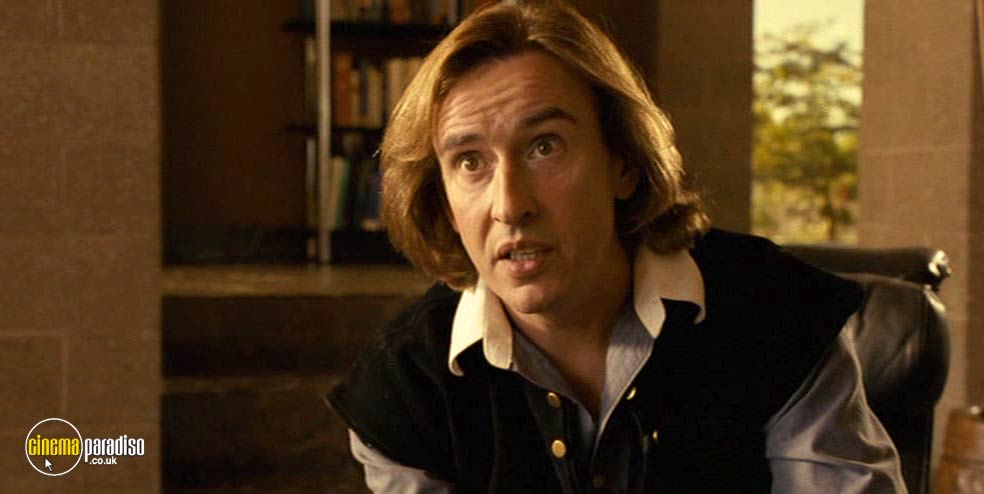

Hamlet 2 (2008)

Play trailer1h 28minPlay trailer1h 28min

Play trailer1h 28minPlay trailer1h 28minWilliam Shakespeare wasn't averse to the odd sequel, especially when writing about kings named Henry. But his play about an indecisive Dane was always a stand-alone until Arizona teacher Dana Marschz (Steve Coogan) decided that his soon-to-close drama department needs to go out with a bang. With Catherine Keener and Amy Poehler in droll support, Andrew Fleming's comedy found few takers on its original release. But the school show itself has its moments, including a time travel interlude and a showstopping song-and-dance number entitled, 'Rock Me Sexy Jesus'.

- Director:

- Andrew Fleming

- Cast:

- Steve Coogan, Elisabeth Shue, Catherine Keener

- Genre:

- Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

Inglourious Basterds (2009)

Play trailer2h 27minPlay trailer2h 27min

Play trailer2h 27minPlay trailer2h 27minBorrowing its title from Enzo G. Castellani's macaroni combat movie, Inglorious Bastards (1978), Quentin Tarantino's Second World War saga incurred much the same critical wrath as Lubitsch's farce had 67 years earlier. A cinema in Paris provides the key setting, as Mélanie Laurent plans to blow up high-ranking Nazis at the premiere of a propaganda film called Nation's Pride. Christoph Waltz won an Academy Award for his portrayal of the pitiless SS officer with a reputation for hunting down Jews, as the film drew eight Oscar nominations.

- Director:

- Quentin Tarantino

- Cast:

- Brad Pitt, Christian Brückner, Hélène Cardona

- Genre:

- Drama, Thrillers, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

303 Squadron (2018) aka: Dywizjon 303 / Squadron 303

Play trailer1h 43minPlay trailer1h 43min

Play trailer1h 43minPlay trailer1h 43minSobinski discovers the plot to betray the underground while stationed in Britain after the fall of Poland. Released shortly after David Blair's Hurricane, Denis Delic's tribute to the Polish pilots who flew with the RAF during the Battle of Britain focusses on the same historical figure. Played respectively by Welshman Iwan Rheon and Pole Maciej Zakoscielny, Jan Zumbach overcame the agony of leaving his homeland and the doubts of his British comrades in order to take on the might of the Luftwaffe in the summer of 1940.

- Director:

- Denis Delic

- Cast:

- Piotr Adamczyk, Kirk Barker, Maciej Cymorek

- Genre:

- Drama, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-