To mark its 60th anniversary, Darling has been restored in 4K and will play in cinemas before being released on disc. Cinema Paradiso reflects on an award-winning snapshot of the Swinging Sixties that has continuously provoked controversy.

When John Schlesinger's Darling (1965) was released in the United States, the prudish middlebrow New York Times critic, Bosley Crowther, declared that the director had 'made a film that will set tongues to wagging and moralists wringing their hands'. In fact, it took half a century for this reaction to occur, as the film was embraced by American audiences in thrall to all things British following the previous year's Beatle-led pop invasion. Indeed, young women were so dazzled by the taboo-busting rebellion on display that they failed to heed the wistfulness of the anti-heroine's lament, 'It should be so easy to be happy, shouldn't it?'

It's only in the #MeToo era that the manipulative misogyny of Darling's toxic male characters has been highlighted and that the motives of director John Schlesinger and screenwriter Frederic Raphael have been scrutinised. Yet the clue was there in the latter's contention that the film's theme had been 'the destruction of the female principle', a sneering boast that found echo in the poster shoutline, 'Shame, shame, everybody knows your name!'

A recent critic opined that, viewed from today's perspective, 'this movie has aged poorly, grotesquely pretentious, and feeling out of touch with reality. Visually too, its flashy style and modishness seem outdated...decades on, the film looks tame, a bit shallow and too much of an allegory about a life devoid of any values or morals.' But this feels unfair and smacks of after the event wisdom, as Darling wasn't made for those dwelling in what they like to think is a more enlightened age. It was created in an attempt to capture an unprecedented moment in British socio-cultural history. No one had made a picture like this before and there were bound to be things that the director wished in retrospect that he could have done differently. But first steps often seem tentative and misdirected. The first blow can't be expected to bring down the entire edifice, but it can create the hairline crack that undermines its integrity.

Of course, six decades on, some of the action looks crude, chauvinist, smug, and self-conscious. But the same could be said of so much transgressive art. Look at Laszlo Benedek's The Wild One (1954) or the stage performances of 1950s rock'n'rollers. They make era-defining icons like Marlon Brando and Elvis Presley look monochromotose - because time, technology, and tastes have moved on. In their day, however, they had a seismic influence on societies built upon deference and acquiescence. Moreover, they awoke the youth of the day and showed them that there was an alnernative way to express themselves and interact with both their elders and their peers.

Critics can look down their noses as judgementally as they like from their hindsightful vantage point on the moral high ground. But they wouldn't be occupying such a loftily self-righteous perch if the artists who came before them had not had the courage to tilt at windmills, even if they didn't always know the best way to go about revealing what director Edgar Wright has called 'the paper-thin reality of cover-story perfection'.

Schlesinger considered that 'Life consists of picking yourself up and trying to go forward.' Despite Darling's focus falling on its female protagonist, this maxim applies equally to the male deuteragonist and tritagonist, as they are also the kind of people pushed to the edge and goaded into making decisions who dominate Schlesinger's oeuvre. He once explained, 'the need to compromise, the fact that nothing is ideal; the need to recognise that compromise and change must be made - a change in one's attitude must occur...that's the theme of a lot of my films.' Survival is also a recurring notion in Schlesinger's features and scholar Julia Prewitt Brown has rightly noted that he also frequently showed how difficult it was 'becoming an adult in an environment that relentlessly promotes fantasies of happiness, success, and wealth'.

Time has exposed the Swinging Sixties as an illusion, in which only the elite got to sample la dolce vita while the rest slogged on with the daily grind. In Darling, Schlesinger teaches the harsh lesson - which is even more relevant in our own social media-driven age of instant gratification and hubristic entitlement - that reality rarely lives up to our hopes and expectations and that the only way to navigate a way through life is to make the best of things.

Monitoring the Situation

John Schlesinger was born in London on 16 February 1926. As the grandson of German-Jewish immigrants who had endured prejudice while striving to make a life in Britain, he always felt something of an outsider. While his grandparents took him to the theatre and the opera as a boy and introduced him to Chaucer and Shakespeare, his parents disapproved of his artistic leanings. Left to look after five children while husband Bernard was stationed in India, Win Schlesinger had little time for the plays that John liked to stage during the school holidays.

His father despaired at his lack of sporting prowess. but he still bought the 11 year-old the 9.5 mm camera that he used to film family holidays. On leaving Uppingham School, Schlesinger served with the Royal Engineers during the last days of the war, making his first amateur film, Horrors, in 1946. While studying at Balliol College, he joined the Oxford University Dramatic Society and became president of the Oxford Experimental Theatre Company. In addition to touring the United States with a selection of Shakespeare plays, Schlesinger also directed the shorts, Black Legend (1948) and Starfish (1952). But his ambition at this time was to become an actor and he appeared on stage in Australia and New Zealand, while also doing radio work back in Britain. He also took bit parts in such features as Charles Crichton's The Divided Heart (1954) and Oh, Rosalinda!! (1955) and The Battle of the River Plate (1956), which were each directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. On reuniting with Roy Boulting on Brothers in Law (1957) after they had collaborated on Sailor of the King (1953), Schlesinger was coaxed into directing the 15-minute documentary, Sunday in the Park (1956). This was noticed at the BBC and Schlesinger was hired as a trainee.

After a stint as a second-unit director - and a gig as a researcher-interviewer on The Valiant Years (1960-61), Anthony Bushell's 27-part Emmy-winning series on Winston Churchill - Schlesinger started producing topical snippets for the magazine show, Tonight (1957-65). These led to him making self-contained items for Huw Weldon's flagship arts programme, Monitor (1958-65). Weldon had already afforded Ken Russell his big break with the trio available from Cinema Paradiso on The Great Composers (2016). Schlesinger would profile Benjamin Britten and Georges Simenon. But he enjoyed the variety the role offered and made films about the circus, seaside piers, children's art, stereo recording, Italian opera companies, student orchestras, and provincial repertory troupes.

There's no doubt that the character of Robert Gold in Darling was inspired by Schlesinger's experiences of trying to make art relevant to the masses without alienating the cogniscenti. One film, The Class, planted another seed, as among the students at the Central School of Speech and Drama was a young Julie Christie, who we recently celebrated in an 85th birthday Getting to Know special. But it was a non-BBC assignment that changed the course of Schlesinger's career.

In 1961, he was commissioned by the British Transport Film Unit to make Terminus, which chronicled a day in the life of Waterloo Station. Shot in the cinéma vérité style found on the BFI's Free Cinema (2006) collection, this 33-minute gem landed the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and a BAFTA. The acclaim earned Schlesinger an invitation from producer Joseph Janni to direct a feature film. As the kitchen sink saga was still in vogue, he selected Stan Barstow's novel, A Kind of Loving (1962), about Yorkshire draughtsman Vic Brown (Alan Bates), who decides to marry girlfriend Ingrid Rothwell (June Ritchie) after she becomes pregnant. Clive Wood and Joanne Whalley took the roles when the book was adapted as a TV serial in 1982.

Suitably impressed, Janni recruited Schlesinger again to direct Billy Liar (1963), which was drawn on the same Keith Waterhouse novel that inspired the TV sitcom, Billy Liar (1973-74). Cinema Paradiso users might notice the similarity to Norman Z. MacLeod's Danny Kaye classic, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947), which was adapted from the inspired writings of American humorist, James Thurber.

Tom Courtenay had been lined up to co-star with actress Topsy Jane before Schlesinger and Janni had been forced to recast the role of Liz at the eleventh hour. As the director later recalled: 'I had made a documentary called Monitor for the BBC [sic] about the Central School of Acting in London. Julie was in one of the classes. She wasn't in the film, but we noted her. She was very striking. When we came to cast Billy Liar, there we were in Joe Janni's office, and there was a magazine which Julie was on the cover of. I pointed at it and said "Someone like her," not recognising her. She came in and tested, twice, and we turned her down. I didn't think she was "earth mother" enough. The other girl who we cast got ill during the first week of shooting and had to drop out. So we went back to the tests and saw Julie, and thought "My God, we're mad! Why didn't we cast Julie?" So we put her in.'

As well as scooping the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, Billy Liar also provided the impetus for Schlesinger's next feature. Newspaper columnist and television personality Godfrey Winn had cameo'd as the radio disc jockey. As the director recalled in a 2000 interview: 'He told me a story about a syndicate of showbiz people who'd rented a flat for a kind of call girl to live in, to whom they all had access, and how she eventually threw herself off the balcony, in Park Lane. We thought that was an interesting premise, but we veered very far away from it. Freddie Raphael came on board to write his script and it was total fantasy. Joe Janni said, "I know a girl who I'd like you to spend time with and follow around, who's the perfect type for this movie." So we spent a lot of time with this girl, and finally a script based to a certain extent on her life, was produced by Freddie, which was much closer to the mark. And we went ahead and made it.'

At the heart of the story was Diana Scott, who was the embodiment of Ingrid's lament in A Kind of Loving that 'it's hard being a girl'. Despite there being plenty of angry young men in British cinema around the turn of the decade, no one had thought to base a film on what it was like to be young and female in a country where many felt they were still essentially second-class citizens. As a gay man in Britain at a time when homosexuality was still illegal, Schlesinger had an insight into the struggle to find acceptance in an uwelcoming world. But he was determined not to tell a sob story.

Years later, he explained: 'We started with the idea of the ghastliness of the present-day attitude of people who want something for nothing. Diana Scott, the principal character, emerged in the script of Darling as an amalgram of various people we had known.' But creating the character proved something of a chore. Godfrey Winn had produced a 10-page outline to guide screenwriter Frederic Raphael. However, he ignored it and concocted his own story, only for Joe Janni to discard it in turn. After spending time with the producer's model friend, Raphael submitted a second draft, which sparked a series of tense exchanges with Schlesinger, who felt that Raphael was still wide of the mark. However, the project was left in tatters when Janni's friend withdrew her co-operation and even threatened an injunction because she needed to protect her reputation during divorce proceedings against her banker husband.

Schlesinger and Raphael were back at square one. Moreover, they had to inform Alec Guinness (who had been cast as the cuckolded spouse) that he would no longer be needed for the denouement, which was due to have taken place during a shooting weekend in the Scottish Highlands. Eventually, after 18 months, a script was agreed. However, Raphael felt compromised, especially after Schlesinger went behind his back when he was out of contact in Greece and asked novelist Edna O'Brien - who has recently been profiled in Sinéad O'Shea's documentary, Blue Road: The Edna O'Brien Story (2024) - to rework a couple of scenes, as she had just adapted her own novel about a young women falling for a married man, The Lonely Girl, for Desmond Davis's Girl With Green Eyes (1964). In an effort to reclaim his characters, Raphael wrote a novelisation of Darling, which often diverges from the script and offers fascinating insights into his interpretation of the story and its dramatis personae.

What's It All About?

While strolling in London, model Diana Scott (Julie Christie) is asked to participate in a vox pop on young people's attitudes to convention that is being conducted by TV arts reporter, Robert Gold (Dirk Bogarde). He is charmed by her unaffected spontaneity and invites her to the BBC to see the programme being edited. They wander by the river and see an old cottage being renovated and speculate about an idyllic existence, even though she is married to Tony Bridges (T.B. Bowen) and he has two young children with his wife, Estelle (Pauline Yates).

Diana accompanies Robert when he travels by train to the country to record an interview with Walter Southgate (Hugo Dyson), an author he values because he has resisted the lure of the capital to become the voice of the provinces. The old man flirts with Diana and Robert is so charmed by her performance that they decide to spend the night together and fake long distance calls to their respective spouses from a phone box at the station.

Quickly tiring of hotel trysts, the pair move in together, with Robert enjoying introducing Diana to the London arts scene. She is receptive, but primarily derives pleasure from being seen to belong to an in-crowd. But she grows bored with being cooped up in the flat while Robert works and flies into a rage when she learns that he has spent time with Estelle while visiting his children.

As part of her work, Diana is asked to help with a charity auction to raise funds for famine relief in Africa. The event is sponsored by the Glass Corporation and is attended by wealthy business types and members of the smart set who fail to see the grotesque irony of young Black boys being dressed as 18th-century pages. Diana revels in the attention and latches on to Miles Brand (Laurence Harvey), a PR man at Glass, who lives in the lap of luxury in company quarters. Diana is attracted by his 'live now' attitude and allows him to land her the title role in Jacqueline, a horror film in which her character is murdered in the opening scene.

At the premiere, Robert realises that Diana is attracted to Miles and he sulks when they get home. She convinces him that Miles is merely useful for her career, as he could arrange for her to become 'The Honey Glow Girl' for an advertising campaign. However, she gets pregnant and has an abortion without telling Robert. She stays with relations in the country while she recovers and is soon reminded how dull respectability and conformity are.

Back in London, Diana gets under Robert's feet at the flat and he urges her to attend a theatre audition. She decides instead to call on Miles at his fencing club and they repair to his new lodgings. They sleep together and Diana tells Robert that she is late home because her car was towed away for being illegally parked. He is unconvinced by the lie, but goes along with it. Robert also accepts that Diana has a modelling job in Paris, when she has actually accepted Miles's invitation to spend the weekend.

Dazzled by the glamour of the City of Light, Diana dresses up to meet Miles's chic friends. She is put out when they gather to watch a couple having sex and feels out of a place at a party when she is made the butt of the joke during a dare game. But she shows her mettle by taunting Miles when it's her turn in the spotlight and she feels pleased with herself for being accepted by such an exclusive bacchanalian coterie. He is less enamoured, but allows her to spend a couple of nights at his apartment after Diana has called Robert to say she's been delayed. Miles also persuades a German client that Diana has the right 'Aryan' appeal to be their 'Happiness Girl'.

Feeling marginalised, Robert becomes cool towards Diana and resents being her plus one at a gallery showing. They argue and he reveals that he has found her plane ticket and knows that she has been cheating on him. He calls her a whore who thinks only of herself and Diana seeks solace in her gay photographer friend, Malcolm (Roland Curram). They go on a shoplifting spree in Fortnum & Mason and impetuously agree to take a holiday when she goes to Italy to shoot a chocolates commercial. Basking in the sunshine, Diana confides that she doesn't really enjoy sex, despite being aware of the power it gives her over important men. Nevertheless, she and Malcolm each have a fling with the same waiter in Capri.

On the set of her advert, Diana meets Prince Cesare della Romita (José Luis de Vilallonga). He was recently widowed, but still proposes to Diana, as he is seeking a stepmother for his seven children. She turns him down and returns to her flat, where Miles is among the guests at a wild party. When he slinks into a bedroom with another woman, Diana seeks to exact her revenge with a stranger. But Robert calls round to see her and draws the wrong conclusion when he sees Miles emerge from Diana's bedroom.

After arguing with Miles, who threatens to destroy her professionally, Diana can feel her options narrowing. She attends Southgate's funeral in the hope of seeing Robert. But he stays away and she decides her best course of action is to marry Prince Cesare and move into his sprawling palazzo. The wedding makes headlines across the continent, but Diana quickly comes to realise she has made a mistake, as her husband often leaves her alone while he visits his mother (and probably a mistress or two) while on business in Rome. One night, after dining in glorious isolation, Diana sheds her clothing while walking back to her room, smashing stuff along the way.

Impulsively, Diana flies back to Britain for a rendezvous with Robert. She feels comfortable with him after they have sex in a country inn. But he is in no mood to listen to her prattle about settling back into their cosy routine, as he only consented to the meeting to settle an old score. While Diana dresses, Robert books her on to a flight to Rome and reveals that he is leaving to teach in an American university. At the airport, he watches from the viewing platform, as Diana regains her composure and deals with the paparazzi with insouciant ease. How long her Italian exile will last is left open, however, as the final shot shows the cover of Ideal Woman magazine to which Princess Diana has given a tell-all interview.

The Making of an It Girl

During the opening negotiations to secure Hollywood funding, Schlesinger and Janni cast Shirley MacLaine as Diana, while Audrey Hepburn and Elizabeth Taylor were also discussed. However, when it became clear that US money would not be forthcoming, Schlesinger flew to Philadelphia to meet Julie Christie, who was on tour with the Royal Shakespeare Company and by no means convinced that acting was the career for her. Despite having been impressed with her cameo in Billy Liar, Schlesinger also had his doubts that Christie could translate Liz's honesty and vivacity into Diana's capricious venality.

Montgomery Clift had been Schlesinger's first choice to play Robert, who was originally an American newspaper columnist. On meeting the actor, however, the director realised that he was a drug-dependent bundle of nerves and he contacted Paul Newman and Cliff Robertson and contemplated Gregory Peck, William Holden, John Cassavetes, and Maximilian Schell before it was decided to place Robert in Schlesinger's old Monitor milieu. Now, Dirk Bogarde seemed the natural fit after having ditched his Rank matinee idol persona through his grittier turns in Basil Dearden's Victim (1961) and Joseph Losey's The Servant (1963).

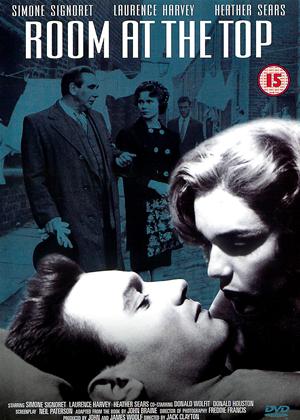

Lithuanian-born South African Laurence Harvey was the first to sign up for his role and his agreement to play Miles Brand convinced Nat Cohen at Anglo-Amalgamated to stump up the almost £300,000 budget, as Harvey's Oscar nomination for Jack Clayton's Room At the Top (1958) had made him a bankable name. At this stage, the picture was going to be called Woman on Her Way. But, while it changed its title, the theme remained the same, as Schlesinger sought to expose 'the ghastliness of the present-day attitude of people who want something for nothing' and show how difficult it was to become 'an adult in an environment that relentlessly promotes fantasies of happiness, success, and wealth'.

Considering the setting was Swinging London, Schlesinger ignored a lot of what was actually happening in the city at the time. Beatlemania might have died down, but the release of Richard Lester's Help! and John Boorman's Dave Clark Five vehicle, Catch Us If You Can (both 1965), showed that pop was still in the vanguard of transforming British society. But the music wasn't to Schlesinger's taste and so the subject was circumvented, although he did go on to direct the video for Paul McCartney's 'Little Willow' in 1997.

Unlike fellow social realists Tony Richardson, Karel Reisz, and Lindsay Anderson, Schlesinger wasn't much of a film buff. Thus, while he could admit to a penchant for such cine-humanists as Jean Renoir, Vittorio De Sica, Akira Kurosawa, and Satyajit Ray, he wasn't interested in the pyrotechnics of the nouvelle vague, despite admiring François Truffaut. Consequently, Darling has always been considered a visually conservative film. But its content, particularly during the Parisian interlude, conveyed something of the feel of European subversion and chic to American audiences who were rarely exposed to such radical escapadism.

Thanks to the Broadway success of Beyond the Fringe, New Yorkers were also au fait with the satire boom, which was still flourishing in Britain, Schlesinger and Raphael borrowed from the lives of Grace Kelly and Christine Keeler (who was still notorious following the 1963 Profumo Case) in creating Diana Scott, with the former's marriage to Prince Rainier of Monaco being nudgingly alluded to in Diana's entombment in Italy. There was even a little dig at Maria's fate at the end of Robert Wise's adaptation of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein's hit stage musical, The Sound of Music (1965), as she also inherits a brood of stepchildren on wedding their aristocratic father.

The opening credit sequence shows billboard posters highlighting food shortages in Africa being covered over by a Mona Lisa-like close-up of Diana advertising her exclusive confidential in Ideal Woman magazine. The joke will be repeated at the auction, where young Black boys are liveried up for the delectation of the guests bidding on items donated to raise money for famine relief. Schlesinger took another pop at casual racism when he had Miles stress Diana's Aryan beauty in pitching her to some German executives.

Another glitzy do, the premiere of Jacqueline, is used to lampoon the Hammer style of horror movie. But Schlesinger misses the opportunity to have Diana mentioned in dispatches as a potential Bond girl, which is just the kind of role to which a 60s It girl would have aspired. He also avoids any reference to the kind of 'grim oop northery' that had done so much to help British cinema rediscover its soul at the end of the 1950s.

One area where Darling did succeed in catching the zeitgeist, however, was costuming, particularly where Diana's wardrobe was concerned. Fresh from dressing The Beatles in Richard Lester's A Hard Day's Night (1964), Julie Harris was on a roll after creating the BAFTA-nominated outfits worn by Samantha Eggar in Alexander Singer's Psyche 59 (1965), another taboo-smashing British drama that tackled even more provocative issues like masochism, child abuse, rape, nymphomania, and psycho-sexual disorder. As time was tight because another designer had failed to match the brief, Harris and Christie went shopping together to buy off-the-peg items that could be tailored to suit Diana's personality and the different functions she would attend. The result was a modish ensemble that was both elegant and glamorous and yet which was also aspirationally affordable for women in the audience.

Schlesinger confessed to being less than au fait with how the other half lived and that he and Raphael had made up the shenanigans in which Miles embroils Diana. Christie was supposedly unnerved by some of the more outré scenes, especially as the shooting schedule meant that she often had no idea how sequences fitted into the overall design. Schlesinger also fragmented the action and frequently made changes to the dialogue and staging instructions. Indeed, Christie found the experience of playing her first lead to be exhausting and disorientating and she could often be found catnapping on the set.

As we saw in the Getting to Know article, Christie came to resent being treated like a marionette and having her suggestions dismissed out of hand. She particularly resented being forced to strip for Diana's strop through the palazzo, as she didn't think the character would behave in such a way. But Schlesinger and Raphael leant on her to do the scene as written and she concurred. The Italian segment contains several nods towards Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941), with the courtship being chronicled in a newsreel before Diana and Cesare are seated at opposite ends of a long dining table that symbolises the emotional distance between them. Charles Foster Kane also smashed up a room out of sheer frustration, but he remained fully clothed,

Dirk Bogarde got on well with Christie and later wrote, 'She has more magnetism or, if you like, star quality than any actress I have worked with.' They were thrown together again after the dubbing sessions at Shepperton Studios when Schlesinger decided that the entire section charting Robert and Diana's friendship wasn't working. In the original montaged version, she had used her looks to get to the front of queues and had flirted with a fishmonger in order to get an extra large cut, Robert had also taken her to Lord's cricket ground as part of her Pygmalion-like education.

But Schlesinger had spent his initial budget. as well as the signing-on fee that Janni had received from David Lean after he had cast Christie as Lara in his adaptation of Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago (1965). Such was the expense of recalling Christie and Bogarde that Janni had to cut a distribution deal with Joseph E. Levine in New York. This windfall allowed Schlesinger to shoot the street interview, the chat in the car park at Television Centre, and the stone-throwing outing to Chiswick Reach.

In his 1978 autobiography, Snakes and Ladders, Bogarde looked back on the events of 13 years earlier. 'It was a very happy film,' he wrote, 'although, predictably, we ran out of money halfway through and no one really believed in it except for the people who were actually involved in it. Joseph Janni, our producer, came sadly into my room one evening at the end of work. Face putty, his eyes hooped with fatigue. "Disaster," he muttered sitting dejectedly on the arm of a chair. "I've mortgaged everything: car, flat, stocks and shares, everything except Stella, my wife. Can you help us? Will you accept a cut in salary and defer your deferments?" The reluctant backers sat glumly through the daily rushes; no big American name, an unknown girl and an, almost, unknown director. They also thought the story was, in the good old Wardour Street word, down beat. Anything that didn't have a happy ending had to be down beat. But the news had spread that something remarkable was happening on Darling. David Lean, at that time casting his epic of Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago asked to see film on both Julie and myself...In the event she won the Oscar for Darling, the little film, and rocketed to stardom in Hollywood. All she ever got out of Zhivago, as far as I know, was a theme song.'

Move Over, Darling

The Moscow Film Festival hosted Darling's world premiere on 15 July 1965. With coverage of Swinging London approaching saturation point in the British media, the picture got a mixed reception from critics before doing merely modest business at the box office. Just as The Observer's Penelope Gilliat had been put off A Kind of Loving by 'the misogyny that has been simmering under the surface of half the interesting plays and films in England since 1956', so Sight and Sound's Penelope Houston took against Darling.

'One day,' she wrote, 'someone is going to make a film about a model (or film star, or beauty queen) with a witty, daring and unconventional theme. The heroine will make a great deal of money; she will live playfully and extravagantly; she will marry even more money. The daring and unconventional aspect will be that she isn't noticeably corrupted by all this. But not yet. To suggest that it could be anything but terrible at the top is apparently more than flesh and blood can stand; and the thing that surprises me about a film like Darling is that people as thoroughly sophisticated as John Schlesinger and Frederic Raphael should accept the constrictions of so many flatly fashionable attitudes.'

She continued: 'Darling is sometimes clever, often ugly, always self-conscious. But its view of the world belongs to the corridors of Wardour Street. Its disillusionment looks like that of a gossip columnist who has left the party with a monumental hangover, but will still be back next day to see how all the awful people are contriving to amuse themselves.' Warming to her task, Houston declared, 'Apart from star-struck adolescents, who aren't presumably the audience Darling has in mind for itself, I believe people in general take a cooler and more sceptical view of show business and advertising than it suits those involved in these trades to imagine. The great glamour image is an advertising man's four-colour illusion. To knock the props from under it, by showing the squalid, shabby, unhappy 'reality' (or, again, half-truth) below the surface, is, in 1965, an act of daring mainly to those within the charmed circle. And to be disenchanted, in any case, one must first have surrendered to an enchantment.'

Refusing to let the makers off the hook, Houston concluded: 'It goes without saying that a good deal of Darling is clever, funny and spitefully accurate. The camera circles and jabs, and the shutter clicks on a freezing moment of self-disclosure. Surprisingly often, however, the filmmakers leave one in doubt about just what value they intend to attach to a scene. Perhaps some modern Savonarola might just pull it off, on his own terms. But that is not the Schlesinger-Raphael method: they are far too knowing, with their snatches of effete dialogue juxtaposed with images of greed and self-satisfaction.'

Six decades later, this remains the prevailing view among critics who consider Darling to be little more than a latterday variation on a Cecil B. De Mille melodrama, in which sin is depicted in luridly shocking detail before it is punished in the final reel. Seen through the #MeToo prism, Diana Scott is plainly a victim of toxic masculinity. Ticking off Schlesinger for stealing ideas from Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Ingmar Bergman, Time Out's Tony Rayns opined that the film 'now looks grotesquely pretentious and out of touch with the realities of the life-styles that it purports to represent,' while David Thomson claimed it 'deserves a place in every archive to show how rapidly modishness withers. Beauty is central to the cinema and Schlesinger seems an unreliable judge of it, over-rating Christie and rarely getting close enough to the action to make a fruitful stylistic bond with it.'

Yet Schlesinger could counter-argue that he hadn't set out to celebrate 60s hedonism or make a documentary record of it. Indeed, he and Raphael had sought to mock the new generation of bright young things and denigrate the 'something for nothing' attitude that would blossom into the hippie ethos of 1967's Summer of Love.

But, while their intentions were dismissed by British critics, they were missed entirely by their American counterparts and an audience that was still keen to embrace any socio-cultural trends from the old country, having surrendered to the British Invasion that had been led by The Beatles in February 1964 - as David Tedeschi pointed out in the Martin Scorsese-produced documentary, Beatles '64 (2024).

Rather than feeling tired and over-exposed, Darling seemed daring and subversive to American viewers. Young women were particularly excited by a narrative that offered them a glimpse of a world in which the shackles of postwar social conservatism had been shattered and they were free to follow their stars - wherever they led - rather than emulate Hollywood role models like Doris Day, whose career women were emancipated and free-spirited right up to the moment that Mr Right came along.

Sheltered by the Production Code that had scarcely shifted its perspective since 1934, female American twentysomethings had never seen a picture that so openly discussed desire, promiscuity, infidelity, age-gap relationships, sexual orientation, living in sin, pregnancy, and abortion with such candour. With Eisenhowerian moral values and Christian conformity still very much in place in most states in the mid-1960s, Darling seemed audaciously cutting edge.

It also seemed exhilaratingly new, especially where Diana's clothing was concerned. Fashion experts credited her with changing how American women dressed and Christie adorned the cover of dozens of magazines embodying the Carnaby Street chic that had unexpectedly made London the couture capital. Time magazine went so far as to proclaim that Christie's sense of affordable style had 'more real impact on fashion than all of the clothes of the Ten Best-Dressed Women combined'.

Behind the 'Darling look' was Julie Harris, who won the last ever Academy Award handed out for Best Costume Design (Black and White). Ironically, the final colour Oscar went to Phyllis Dalton for Doctor Zhivago, which, of course, also starred Julie Christie. Despite winning the award for Best Actress, Christie took no pleasure in being the category's first winner to appear naked. After Rex Harrison had presented her with the statuette at the 38th ceremony at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium on 18 April 1966, she managed to exclaim through gasps of astonishment: 'I don't think I can say anything...except to thank everyone concerned, and especially my darling John Schlesinger, for this wonderful honour. Thank you.'

Connie Stevens accepted on behalf of an absent Frederic Raphael. But he would prevail again at the BAFTAs, as would Christie. Dirk Bogarde took Best Actor, while Ray Simm received the award for Best British Art Direction (Black and White) for the splendid interiors that contrasted Diana's married bedsit, her love nest with Robert, Miles's borrowed abodes, and the prince's palatial villa. On top of the glittering prizes came a gross of $4.5 million, the bulk of which was amassed in the United States.

Schlesinger rather despaired that a film intended to expose the shallowness of the rich and fashionable came to be seen as a celebratory snapshot of an epochal moment. As a closeted gay man, Schlesinger recognised Diana as a fellow outsider. He thus followed the bisexual Tony Richardson's lead in A Taste of Honey (1962) in giving his heroine a gay confidante. Indeed, he went further in seating Diana next to a trans women at the live sex show in Paris, where cross-dressing was accepted without qualm at the surreal soirée.

Ray Galton and Alan Simpson had lampooned such pseudishness in Robert Day's The Rebel (1961), which took several of its cues from Stanley Donen's Funny Face (1957). Schlesinger clearly had Federico Fellini's La dolce vita (1960) in mind, but he lacked the Italian's talent to scandalise. As a result, Darling can seem staid and judgemental, as it appears to approve of the taming of what the publicity material called 'a girl who wants something for nothing and in the end gets nothing for nothing'.

Diana is exploited by predators, who prove as superficial, fickle, amoral, and selfish as she is depicted as being. But compare her to all those women in the kitchen sink dramas that came before. She's the kindred spirit of Liz, who leaves Billy behind and takes the train to that London to live on her own terms. As Melanie Williams says in her excellent essay in the booklet accompanying Studio Canal's 60th anniversary home entertainment release: 'Diana brought something new into British cinema, giving expression to an evolving female identity that could not be contained by the film's moralising framework...Darling showed "a woman who didn't want to get married, didn't want to have children like those other kitchen sink heroines. No, Darling wanted to have everything. Of course, at the time this was seen as greedy promiscuity and she had to be punished. But there was an element of possibility there for women, of a new way of living, which is why the film was such a success." Film critic Marjorie Rosen concurred, even seeing a kind of emergent feminism in the contours of discontent the film outlined: 'a woman saying "My role in this world is not enough".'

Unlike Ingrid in A Kind of Loving, Diana doesn't settle for a shotgun marriage. She shapes her own destiny by making her own decisions. Ultimately, they land her in a mausoleum to patriarchal power. But Prince Cesare is much older than Diana and there's no knowing how much longer he might have to live - which would leave her as a merry widow, with a title and an annuity. It was still hard being a girl in the mid-1960s, as, indeed, it is now. But, as academic Robert Murphy concludes, 'Diana's life might be empty, superficial and ultimately sad, but it still seems more fun than working in Woolworths.'

-

Pandora's Box (1929) aka: Die Buchse der Pandora

2h 11min2h 11min

2h 11min2h 11minEveryone loves Lulu (Louise Brooks). Following a tragedy after both newspaper editor Ludwig Schön (Fritz Kortner) and his son, Alwa (Francis Lederer), fall for her, Lulu has to rely on the help of the scheming Schigolch (Carl Goetz) and lesbian countess, Augusta Geschwitz (Alice Roberts).

- Director:

- Georg Wilhelm Pabst

- Cast:

- Louise Brooks, Fritz Kortner, Francis Lederer

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

All About Eve (1950)

Play trailer2h 12minPlay trailer2h 12min

Play trailer2h 12minPlay trailer2h 12minAspiring actress Eve Harrington (Anne Baxter) uses her wiles to exploit theatre critic Addison DeWitt (George Sanders), playwright Lloyd Richards (Hugh Marlowe), and director Bill Sampson (Gary Merrill) in her bid to topple Broadway queen bee, Margo Channing (Bette Davis).

- Director:

- Joseph L. Mankiewicz

- Cast:

- Bette Davis, Anne Baxter, George Sanders

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Room at the Top (1958)

Play trailer1h 53minPlay trailer1h 53min

Play trailer1h 53minPlay trailer1h 53minSocially ambitious Joe Lampton (Laurence Harvey) seeks to make his mark on the Yorkshire town of Warnley by dating Susan (Heather Sears), the daughter of a local factory owner. When he forbids the match, Joe consoles himself with Alice (Simone Signoret), an older Frenchwoman trapped in a loveless marriage.

- Director:

- Jack Clayton

- Cast:

- Laurence Harvey, Simone Signoret, Heather Sears

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

La Dolce Vita (1960) aka: The Sweet Life

Play trailer2h 46minPlay trailer2h 46min

Play trailer2h 46minPlay trailer2h 46minAway from his problems with fiancée Emma (Yvonne Furneaux), mistress Maddalena (Anouk Aimée), and visiting film star Sylvia (Anita Ekberg), tabloid journalist Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni) envies the cultured lifestyle of his writer friend, Steiner (Alain Cuny).

- Director:

- Federico Fellini

- Cast:

- Marcello Mastroianni, Anita Ekberg, Anouk Aimée

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962) aka: Cléo de 5 à 7

Play trailer1h 30minPlay trailer1h 30min

Play trailer1h 30minPlay trailer1h 30minWhile awaiting the results of a biopsy, superstitious singer Cléopâtre Victoire (Corinne Marchand) kills time with assistant Angèle (Dominique Davray) and life model friend, Dorothée (Dorothée Blank). However, she feels less stressed in the company of Antoine (Antoine Bourseiller), a stranger who is on leave from the Algerian War.

- Director:

- Agnès Varda

- Cast:

- Corinne Marchand, Antoine Bourseiller, Dominique Davray

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

Alfie (1966)

Play trailer1h 49minPlay trailer1h 49min

Play trailer1h 49minPlay trailer1h 49minRefusing to marry the pregnant Gilda (Julia Foster), Cockney chauffeur Alfie Elkins (Michael Caine) has flings with married women, Siddie (Millicent Martin) and Lily (Vivien Merchant), while also pursuing naive hitchhiker Annie (Jane Asher) and blowsy visiting American, Ruby (Shelley Winters).

- Director:

- Lewis Gilbert

- Cast:

- Michael Caine, Shelley Winters, Millicent Martin

- Genre:

- Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Georgy Girl (1966)

Play trailer1h 35minPlay trailer1h 35min

Play trailer1h 35minPlay trailer1h 35minScatty twentysomething Georgina Parkin (Lynn Redgrave) resists the attentions of her father's employer, James Leamington (James Mason), but develops a crush on Jos Jones (Alan Bates), the boyfriend of her pregnant violinist flatmate, Meredith Montgomery (Charlotte Rampling).

- Director:

- Silvio Narizzano

- Cast:

- James Mason, Alan Bates, Lynn Redgrave

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Far from the Madding Crowd (1967)

2h 40min2h 40min

2h 40min2h 40minBathsheba Everdene (Julie Christie) hires shepherd Gabriel Oak (Alan Bates) after inheriting her uncle's farm in the 1860s West Country. She feels drawn to wealthy neighbour, William Boldwood (Peter Finch). But, no sooner has he proposed than Bathsheba becomes smitten with red-uniformed soldier, Frank Troy (Terence Stamp).

- Director:

- John Schlesinger

- Cast:

- Julie Christie, Peter Finch, Alan Bates

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Scandal (1989)

Play trailer1h 50minPlay trailer1h 50min

Play trailer1h 50minPlay trailer1h 50minTrouble ensues when society osteopath Stephen Ward (John Hurt) introduces married cabinet minister John Profumo (Ian McKellen) to dancer Christine Keeler (Joanne Whalley) and her party-loving friend, Mandy Rice-Davies (Bridget Fonda).

- Director:

- Michael Caton-Jones

- Cast:

- John Hurt, Joanne Whalley, Bridget Fonda

- Genre:

- Drama, Thrillers, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Vanity Fair (2004) aka: Vanidad

Play trailer2h 15minPlay trailer2h 15min

Play trailer2h 15minPlay trailer2h 15minHoping to use her friendship in 1804 London with Amelia Sedley (Romola Garai) to land herself a good position, Becky Sharp (Reese Witherspoon) attracts the attention of Amelia's beau, George Osborne (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), as well as Rawdon Crawley (James Purefoy), the son of her employer, Sir Pitt Crawley (Bob Hoskins).

- Director:

- Mira Nair

- Cast:

- Reese Witherspoon, Romola Garai, James Purefoy

- Genre:

- Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-