Nine decades ago this spring, at the height of the Great Depression, Paramount Pictures went bankrupt with debts of $21 million. In the midst of such upheaval, the studio still produced some of the funniest comedies in Hollywood history. Cinema Paradiso discovers what kept the laughs coming.

After Universal, Paramount is the second-oldest studio in the United States. Based at 5555 Melrose Avenue, it's the only one of the 'Big Five' from Hollywood's heyday to still be located within the city limits of Los Angeles. With 11 Best Picture wins to its credit, it stands second only to Universal (with 12) in the Oscar stakes. But Paramount can lay claim to being the keystone of the studio system, as it pioneered the vertical integration model of combining production, distribution, and exhibition in one company that enabled Hollywood to become the biggest player in world cinema.

Zukor & Co.

Paramount Pictures began life as the Famous Film Company, which was founded by Hungarian émigré Adolph Zukor in 1912. He had started out in the nickleodeon business and realised that moving pictures were not just a novelty that could amuse the lower classes. He also saw that they had an artistic potential that could entice educated theatregoers. Consequently, he started investing in prestige productions, such as Louis Mercanton and Henri Desfontaines's Queen Elizabeth (1912), a four-reel import from France that starred stage legend Sarah Bernhardt.

Buoyed by this success, in 1916, Zukor merged Famous Players with Jesse Lasky's production company and the Paramount distribution unit that had been founded by William Wadsworth Hodkinson. Boasting studios in New York and Los Angeles, the new corporation started offering generous salaries to stars of the magnitude of Pola Negri, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Gloria Swanson, and Rudolph Valentino. The latter became cinema's first pin-up heart-throb in George Melford's The Sheik (1921) and Fred Niblo's Blood and Sand (1922), while director Cecil B. DeMille played a crucial part in the studio's rise, as he switched from saucy comedies of manners to epics like The Ten Commandments (1923) and King of Kings (1927).

Exploiting a 'star system' boosted by the signing of Clara Bow, Mae Murray, and John Barrymore, Zukor instigated a 'block booking' policy that forced exhibitors to take minor Paramount offerings in return to guaranteed access to the big money makers. Realising he could corner the market by owning his own cinemas, Zukor bought the Chicago-based Balaban and Katz chain in 1925. This meant that 1200 venues across the country became dedicated Paramount outlets, as the studio churned out around 100 features a year in the late silent era.

Among them was William A. Wellman's Wings (1927), which won the inaugural Academy Award for Best Picture and gave Paramount momentum as it converted to sound with Richard Wallace's Innocents of Paris (1929), which made a Stateside star of French boulevardier, Maurice Chevalier. A house style started to emerge under production chief B.P. Schulberg, who coined the slogan, 'If it's a Paramount Picture, it's the best show in town.'

By luring such Europeans as Ernst Lubitsch, Rouben Mamoulian, and Josef von Sternberg to the studio, Schulberg was able to foster an air of continental chic that was reinforced by imported stars like Cary Grant and Marlene Dietrich, who joined a roster of homegrown talent that included Gary Cooper, Claudette Colbert, Fredric March, William Powell, and Carole Lombard. As a result, Paramount posted unprecedented profits of $18.4 million in 1930. Two years later, however, the studio broke another Hollywood record in reporting a $21 million loss that led to the studio filing for bankruptcy in early 1933 and being placed in the hands of trustees.

Lasky and Schulberg paid the price for the collapse, while Zukor was shuffled into an honorary position. Sam Katz steadied the ship by securing new finance. But it was former partner Barney Balaban whose three-year recovery plan proved so effective that he remained in control for three decades. Shrewd management after a period of reckless spending certainly helped. But what replenished the Paramount coffers were a clutch of comedies starring performers who had all started out on the stage.

The Importance of Being Ernst

As both director and producer-cum-executive, Ernst Lubitsch was pivotal to the evolution of Paramount's comic style in the 1930s. Born in Berlin in January 1892, he had been bitten by the acting bug at school and upset his draper father by sneaking away from the family shop at nights to perform in variety shows. In 1911, he joined Max Reinhardt's famous Deutsches Theater and started supplementing the income from playing character parts by working as a handyman at the Bioscope film studio.

Within a year, Lubitsch started making short comedies and turned actor-director with Fräulein Seifenschaum (1914). In addition to creating slapstick gems, Lubitsch also perfected a Jewish everyman in 'milieu films' like Shoe Palace Pinkus (1916) and Meyer From Berlin (1919). Heavily reliant on stereotypes, they could easily offend modern sensibilities. Yet, even though Lubitsch's shtick was broad in the extreme, these camp satires on assimilation and anti-semitic perceptions were hugely popular with German Jewish audiences, who recognised who was the real butt of the humour.

Nevertheless, it's hard to believe that the Meyer comedies were made by someone who was considered 'a man of pure cinema' by Alfred Hitchcock, 'a giant' by Orson Welles, and 'a prince' by François Truffaut, who also opined, 'In the Lubitsch Swiss cheese each hole winks.'

Such admiration is more explicable from the features that Lubitsch directed in the early days of the Weimar Republic, when he realised that his future lay behind the camera. He had made over 20 films before he earned critical acclaim for a pair of Pola Negri dramas: The Eyes of the Mummy and Carmen (both 1918). But, having acted for the final time in Sumurun (1920), Lubitsch discovered his métier for witty social satire with The Oyster Princess and The Doll (both 1919), which can be rented from Cinema Paradiso on high-quality DVD and Blu-ray as part of the six-film set, Lubitsch in Berlin, which also includes I Don't Want to Be a Man (1918) and Die Bergkatze (1921).

Lubitsch carried over his virtuoso visual wit into a trio of historical romps - Madame Du Barry (1919), Anna Boleyn (1920), and The Loves of Pharaoh (1921) - which resulted in 'the Griffith of Europe' receiving an invitation from Mary Pickford to direct her in Rosita (1923). Despite finding America's Sweetheart a nightmare to work with, Lubitsch scored a critical success and signed a three-year contract with Warner Bros. However, while he was afforded unprecedented creative freedom and reviewers started enthusing about his celebrated 'touch' following The Marriage Circle (1924), Lubitsch only enjoyed moderate box-office success with Forbidden Paradise (1924), Kiss Me Again, Lady Windermere's Fan (both 1925), and So This Is Paris (1926). Consequently, Warners allowed MGM and Paramount to buy out the remainder of his contract.

He charmed the critics again with The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (1927) and earned an Academy Award nomination for The Patriot (1928), which marked the last of his seven collaborations with Emil Jannings, who had just won the inaugural Oscar for Best Actor for his work in Victor Fleming's long-lost The Way of All Flesh (1927) and Josef von Sternberg's The Last Command (1928). But, even though directors across Hollywood were trying to emulate 'the touch', the embarrassing failure of the romantic melodrama, Eternal Love (1929), led some to wonder, as the talkies started to capture the public imagination, whether Lubitsch's patented brand of laconically urbane entertainment had come to seem a little old fashioned.

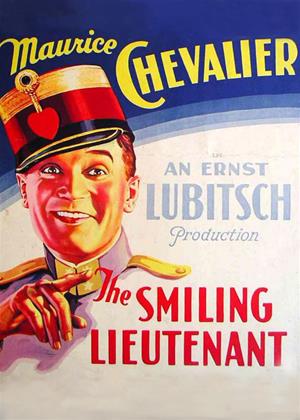

Lubitsch's silents had always exhibited a kind of musicality and it seemed inevitable that he should turn his hand to musicals following the introduction of sound in 1927. In The Love Parade (1929), however, he refused to follow the rubric of slotting songs into convenient places in the narrative by making them an integral part of the action. He also made innovative use of recitative to form bridges between the dialogue and the lyrics. Having earned his second Oscar nomination for this droll Ruritanian teaming of Jeanette MacDonald and Maurice Chevalier, he reinforced his reputation as the maestro of the new genre by directing MacDonald in Monte Carlo (1930) and Chevalier in The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), which marked his first collaboration with screenwriter Samuel Raphaelson, who had been partially responsible for the talkie boom, as his short story, 'The Day of Atonement', had been adapted for the big screen as Alan Crosland's The Jazz Singer (1927).

As cinema attendances dropped during the Great Depression, the Hollywood studios were forced to slash budgets and salaries in the face of plummeting profits. Following the failure of a rare venture into melodrama with The Man I Killed (1932), Lubitsch found himself under pressure at Paramount and agreed to combine his directing duties with the role of production chief.

No other film-maker of Lubitsch's calibre took on such an administrative role during the Golden Age of Hollywood. He encouraged writers to capitalise on their relative Pre-Code freedom by lacing their scripts with an ironic wit and sophisticated innuendo that he also expected of visuals that were given additional elegance by the art department that was the fiefdom of Lubitsch's compatriot, Hans Dreier, between 1927-50.

Having produced the portmanteau comedy, If I Had a Million, Lubitsch signed up for a similar role on George Cukor's One Night With You (both 1932). This saucy musical reunited Chevalier and MacDonald. But Lubitsch was so dismayed by Cukor's leaden direction of his two favourite stars that he took over on the third day of shooting. Following their triumphant collaboration with Herbert Marshall and Kay Francis on Trouble in Paradise (1932), Miriam Hopkins and Lubitsch reunited on his adaptation of Noël Coward's Design for Living (1933), which co-starred Gary Cooper and Fredric March.

The arrival of Joseph I. Breen at the Production Code Administration in 1934 saw a stricter enforcement of the rules governing screen content, however, and Lubitsch took a sabbatical from directing after his final teaming with MacDonald on The Merry Widow (1934), which was produced by MGM. Devoting himself to backstage duties at Paramount, he tried to work out how to adapt his effervescent style to the new circumstances. The fact that he followed his comeback picture, Angel (1937), with such peerless comedies as Bluebeard's Eighth Wife (1938), Ninotchka (1939), The Shop Around the Corner (1940) and To Be or Not to Be confirms that he found a way.

However, he left Paramount in 1939 and followed brief spells with MGM and United Artists by finding a berth at 20th Century-Fox. Having misfired with That Uncertain Feeling (1941), Lubitsch slowed down considerably after completing Heaven Can Wait (1943). Illness forced him to hand A Royal Scandal (1945) over to Otto Preminger before he returned to form with the sadly undervalued Cluny Brown (1946). Tragically, at the age of just 55, Lubitsch suffered a fatal heart attack while shooting That Lady in Ermine (1948), which was again passed to Preminger to complete. On leaving the funeral in December 1947, fellow director William Wyler sighed, 'No more Lubitsch,' to which Billy Wilder replied, 'Worse than that. No more Lubitsch pictures.'

Come What Mae

'The rest of America could ask for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,' Mae West wrote in her autobiography. 'I'd take the spotlight.' Indeed, when the seven year-old debuted at the Royal Theatre in Brooklyn, she stamped her foot on the stage to ensure that the beam was trained on her before she started singing 'Movin' Day'. That one act of assertiveness set the tone for the next eight decades.

Mary Jane West was born in Brooklyn on 17 August 1893. The first of three children born to a bare-knuckle boxer and a corset model, Mae began performing at a church social at the age of five and was soon scooping prizes at amateur talent shows. At the age of 14, she hit the vaudeville circuit as 'Baby Mae' and was briefly billed as a male impersonator while she refined her stage persona.

Having recklessly married double act partner Frank Wallace, West ditched him to make her bow on the Great White Way in the 1911 review, A la Broadway. Undaunted by its failure, she shared the bill with Al Jolson in Vera Violetta before making headlines for the first time in 1918, with her shimmy dance in the Shubert Brothers revue, Sometime.

Bored with the material being offered her, West adopted the pen name Jane Mast to write Sex, a 1926 play that proved such a succès de scandale (in spite of damning reviews) that she was playing to packed houses when religious groups demanded action. On 19 April 1927, West was found guilty of 'corrupting the morals of youth' and served four-fifths of a 10-day sentence, which she milked for maximum publicity.

She reinforced her bad girl reputation with her next play, The Drag, which was prevented from opening in New York, as it condoned homosexuality. Over the next four years, she endured mixed fortunes with The Wicked Age (1927), The Pleasure Man, Diamond Lil (both 1928), and The Constant Sinner (1931), as the public flocked to be shocked in spite of sniffily disapproving reviews.

Feeling she had conquered the stage, West took the train to Hollywood in June 1932, where she demanded complete control over every aspect of her pictures and a salary that was one dollar higher than that of Paramount chief Adolf Zukor. Needing rescuing from the Depression, the studio agreed to each demand, as the 39 year-old made her screen debut in Archie Mayo's Night After Night (1932). Maudie Triplett was only a supporting role in a drama that centred on the romance between a speakeasy owner (George Raft) and a hard-up socialite (Constance Cummings). But West rewrote her lines and, according to Raft, 'stole everything but the cameras'.

Having reworked Diamond Lil for Lowell Sherman's She Done Him Wrong (1933), West insisted on relative newcomer Cary Grant being cast as the G-man working undercover at the Bowery mission adjoining the saloon where chanteuse Lady Lou has punters and lowlifes eating out of her hand. The dialogue dripped with double entendres, as West redefined the notion of a sex symbol. Despite the Depression biting deeply, the bawdy comedy raked in over $2 million and saved Paramount from extinction.

Moreover, she snagged an Oscar nomination for Best Picture and the 66-minute romp remains the category's shortest nominee. A second nod followed for Wesley Ruggles''s I'm No Angel (1933), for which West did her own lion-taming stunts as Tira, a shimmy dancer who lands herself a rich beau. Grant co-starred again, although he resented West's assertion that she had discovered him, as he had already made his name at Paramount opposite Marlene Dietrich in Josef von Sternberg's Blonde Venus (1932).

Such was her impact on Tinseltown that Variety opined, 'Mae West's films have made her the biggest conversation-provoker, free-space grabber, and all-around box office bet in the country. She's as hot an issue as Hitler.' Within a year, she would become the highest paid woman in the country. But her tight corsets, drawled dialogue, and sashaying strut incurred the wrath of America's moral guardians, who saw her films as vulgar and grotesque. They certainly flew in the face of the Hollywood template, as a middle-aged woman of unconventional beauty had men falling at her feet, while she mocked authority, disregarded propriety, and celebrated her sass and sexuality. Moreover, West played confident, independent women who didn't rely on any man and this was seen as dangerous during the Depression when American masculinity was in crisis and it was deemed necessary for women to be kept in their place while male esteem was restored.

In order to draw West's sting, the tenets of the Production Code that had been largely ignored since their drafting in 1930 were forcibly imposed upon Hollywood on 1 July 1934. Under staunch Catholic Joseph I. Breen, the Code Administration assumed the right to censor screenplays before shooting began and withhold a seal of approval from pictures that refused to conform. Paramount agreed to change the title of West's next vehicle from It Ain't No Sin to Belle of the Nineties, while numerous wisecracks were toned down or removed from the story of an 1890s St Louis vaudeville star and her boxer beau. Leo McCarey's slick direction helped compensate for the bowdlerisation, as did the presence of Duke Ellington and his orchestra, who was expressly cast at West's insistence, even though Hollywood tried to avoid mixing races within scenes in order to avoid offending audiences below the Mason-Dixon Line.

Another enforced title change resulted in Now I'm a Lady being released as Goin' to Town (1935). Directed by Alexander Hall, the tale of saloon singer Cleo Borden's bid to seduce dashing Brit Edward Carrington (Paul Cavanaugh) after inheriting an oil-rich ranch proved popular at the box office. But, despite stuffing the screenplay with bawdy gags in the hope that Breen would overlook the subtler innuendo, West was frustrated by the number of compromises she was being forced to make.

Her troubles increased when press baron William Randolph Hearst took exception to a quip about his actress paramour, Marion Davies, and instructed his newspapers to bury Raoul Walsh's Klondike Annie (1936). The PCA also took umbrage with a plot that sees kept woman Rose Carlton assume the identity of a deceased nun, Sister Annie Alden, while heading to Alaska after killing her possessive lover in self-defence. Exposing religious hypocrisy, this was West's most overtly satirical film. But Paramount flinched in the face of Hearst's calls for Congress to investigate her malign influence and ordered her to tone down the humour in Henry Hathaway's Go West, Young Man (1936), which she had adapted from Lawrence Riley's Broadway hit, Personal Appearance. Cary Grant's onetime roommate, Randolph Scott, co-starred as Bud Norton, the small-town mechanic who catches the eye of movie diva Mavis Arden when her Rolls-Royce breaks down in the back of beyond. But West felt betrayed and found herself out of contract after A. Edward Sutherland's Every Day's a Holiday (1937), in which fin-de-siècle con artist Peaches O'Day poses as a chanteuse named Fifi after being caught trying to sell the Brooklyn Bridge.

Adding to her woes, West was included alongside Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Katharine Hepburn, Joan Crawford, and Fred Astaire on the infamous 'Box-Office Poison' list compiled by Harry Brandt on behalf of the Independent Theatre Owners Association. Nevertheless, David O. Selznick offered West the part of Belle Watling that would eventually be taken by Ona Munson in Victor Fleming's Gone With the Wind (1939).

Instead, West took herself to Universal to join forces with W.C. Fields in Edward F. Cline's My Little Chickadee (1940). The pair disliked each other enormously, but they traded quips amiably enough after Chicago singer Flower Belle Lee and con man Cuthbert J. Twillie are drawn together over a stash of cash in Greasewood City on the 1880s frontier. Resentful of Fields being given a scripting credit when she had done most of the work, West resisted a reunion, as she returned to Broadway. Three years later, however, she answered a call from old friend Gregory Ratoff to play Fay Lawrence in The Heat's On (1943), a Columbia comedy about a Broadway impresario who enters an unholy alliance with a censor in order to coax his star out of the clutches of his biggest rival.

In essence, West was reduced to a supporting role and, rather than spend her fifties playing matrons and spinsters, she followed a Broadway stint in Catherine Was Great (1944) by attempting to conquer the airwaves. However, she was effectively barred after a suggestive encounters with ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and dummy Charlie McCarthy and an Adam and Eve sketch with Don Ameche. Consequently, she divided her time between cabaret engagements in Las Vegas, nightclub appearances, and stage revivals. She would later record a string of albums, including Way Out West (1966), which saw her put a unique spin on some pop classics.

She turned down Billy Wilder's offer of the role of Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard (1950) and George Sidney's invitation to play Vera Simpson opposite Frank Sinatra in Pal Joey (1957). The prospect of being Elvis Presley's boss in John Rich's Roustabout (1964) proved no more appealing, while she ignored Federico Fellini's entreaties to participate in Juliet of the Spirits (1965) and Satyricon (1969).

West did consent, however, to her image appearing on the cover of Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) after The Beatles had written personally to assure her of their devotion after she had inquired, 'What would I be doing in a Lonely Hearts Club?'

Three years later, West ended her 27-year exile from the screen when she played libidinous casting agent Leticia Van Allen opposite Raquel Welch in Michael Sarne's adaptation of Gore Vidal's Myra Breckinridge (1970). The scenario riffed on the fact that West had surrounded herself with rippling bodybuilders in her Vegas shows (indeed one, Paul Novak, would become her inseparable companion for 26 years). And her status as a left-field feminist icon would be further celebrated in Ken Hughes's Sextette (1978), which Herbert Baker updated from West's unrealised 1959 script.

Alongside her as the much-married Marlo Manners are Timothy Dalton as her new husband, Tony Curtis, George Hamilton, and Ringo Starr as her exes, Keith Moon as her dress designer, and Alice Cooper as a waiter. Bringing things full circle, West and George Raft reunited on a Paramount soundstage after 46 years. But it was a troubled shoot, as the 84 year-old star had failing eyesight and had to be fed lines through an earpiece. She would die two years later, but left behind a legacy whose impact is only just being recognised by feminist scholars, as Julia Marchesi and Sally Rosenthal outline in the excellent PBS documentary, Mae West: Dirty Blonde (2020).

W.C. Fields Forever

With his bulbous nose, distinctive drawl, fondness for liquor, and loathing of children and dogs, W.C. Fields was an unlikely star. But he rivalled Charlie Chaplin in terms of popularity in the early 1930s and continues to inspire comedians almost a century later.

William Claude Dukenfield was born on 29 January 1880 in Darby, Pennsylvania. Forced to work on his father's vegetable cart, he taught himself to juggle and ran away from home at the age of 11. Breaking into vaudeville, he was billed as 'The Distinguished Gentleman' and initially worked in silence to hide a stammer. But Fields discovered he got laughs if he made the odd mistake and grumbled at his props.

Having made his Broadway debut in the 1905 musical comedy, The Ham Tree, Fields started touring abroad. During a visit to Britain, he was invited to perform at Buckingham Palace. Back in New York, he spent six years with Florenz Ziegfeld's fabled Follies revue, where he developed the sketches that would later be immortalised on film. He shot Pool Sharks (1915) at Gaumont's studio in Flushing, New Jersey and Cinema Paradiso users can enjoy it as part of The W.C. Fields Extravaganza.

This three-disc set also contains D.W. Griffith's Sally of the Sawdust, an adaptation of Fields's stage success, Poppy, which brought him to Paramount's Astoria Studios. Following a reunion with Griffith on the lost comedy, That Royle Girl (both 1925), Fields teamed with Marion Davies in Janice Meredith and Louise Brooks in It's the Old Army Game. Sadly, this isn't available on disc, as aren't So's Your Old Man (both 1926) and Running Wild, while The Potters (both 1927) has been lost entirely. But these features established Fields as an accomplished silent clown. Unlike many of his peers, however, he was even more comfortable in front of a microphone.

Easing himself into talkies, Fields ditched the false moustache he had worn in his silent outings and dusted down some old stage sketches for a string of two-reelers for slapstick king, Mack Sennett. Cinema Paradiso users can rent The Golf Specialist (1930), The Dentist (1932), The Fatal Glass of Beer, The Pharmacist, and The Barber Shop (all 1933) on either W.C. Fields: Classic Shorts or W.C. Fields: 6 Classic Shorts. Frustratingly, though, we can't bring you Fields's first sound feature, Her Majesty, Love (1931), which he made at Warner Bros. with Broadway legend, Marilyn Miller.

Eager to avoid losing Fields to another studio, Paramount offered him a long-term contract that made him one of the best paid comics in the business. Cashing in on the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics, Edward F. Cline's Million Dollar Legs followed the efforts of the President of Klopstokia to save his country from bankruptcy by winning the cash prize that goes with the gold medal for weightlifting. Contrasting with such madcap surrealism, Norman Z. McLeod's 'Road Hogs' contribution to the 1932 anthology, If I Had a Million, was pure slapstick, as vaudevillians Rollo and Emily La Rue (Alison Skipworth) spend a windfall on eight disposable cars to teach some dangerous drivers a lesson.

In A. Edward Sutherland's International House, wayward steering sends Professor Henry R. Quail's autogyro into the grounds of the Chinese hotel where an inventor is showing off his televisual device. Billed as ' The Grand Hotel of Comedy', this loose collection of songs and sketches also featured George Burns and Gracie Allen, the much-loved husband-and-wife team whose ditzy brand of humour can also be enjoyed by Cinema Paradiso members in George Stevens's A Damsel in Distress (1937) and Raoul Walsh's College Swing (1938).

Having guested as Humpty-Dumpty in Norman Z. McLeod's take on Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland, Fields hooked up with Alison Skipworth again for Francis Martin's Tillie and Gus, as the estranged Winterbottoms come together in order to renovate a paddle steamer and compete in a race to secure a lucrative ferry franchise. Fields and Skipworth would bandy words again as the Nuggetville sheriff and innkeeper who encounter travelling couples Charles Ruggles and Mary Boland and George Burns and Gracie Allen in Leo McCarey's Six of a Kind (1934).

A busy year would see Fields make four more features, including the regrettably unavailable Mrs Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch. In Erle C. Kenton's You're Telling Me, he plays optometrist Samuel Bisbee, who moonlights as an amateur inventor and is delivered from a sticky predicament by a passing princess. This sound remake of So's Your Old Man was followed by William Beaudine's The Old-Fashioned Way, which cast Fields as The Great McGonigle, whose touring theatre troupe is performing in the 1844 temperance play, The Drunkard. Allowing Fields to showcase his juggling skills, this riotous romp also saw him renew contact with child star Baby LeRoy, who would also darken the door of Harold Bissonette, who decides to swap his grocery store for an orange farm in Norman Z. McLeod's It's a Gift (all 1934).

A fine example of a Fields comedy in which a decent everyman is worn down by the demands of his ghastly family, this gem was followed by two less typical ventures. As a latecomer to books, Fields had a passion for Charles Dickens and lobbied for the part of Wilkins Micawber in George Cukor's MGM adaptation of David Copperfield. He returned to Paramount to be teamed for the only time with the studio's new crooning sensation, Bing Crosby, in A. Edward Sutherland's Mississippi (both 1935), a musicalisation by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart of a Booth Tarkington novel about a coward who seeks refuge aboard the riverboat skippered by Commodore Orlando Jackson.

More domestic misery was heaped upon memory expert Ambrose Wolfinger, as he tries to enjoy a day off and attend a wrestling match in Clyde Bruckman's Man on the Flying Trapeze (1935). Co-scripting as Charles Bogle, Fields did some uncredited directing with friend Sam Hardy, whose sudden death exacerbated a period of ill health that would eventually keep Fields off the screen for a year. Despite drinking so heavily that he often forgot his lines, he battled on in Eddie Sutherland's Poppy (1936) in the familiar role of snake oil salesman Professor Eustace P. McGargle, which he had already played on stage and in Sally of the Sawdust.

Under pressure from the Paramount front office and companion Carlotta Monti (whose autobiography would be filmed by Arthur Hiller as W.C. Fields and Me, 1976), Fields took time off. But, in returning to play sibling liner owners T. Frothingill Bellows and S.B. Bellows, he feuded openly with director Mitchell Leisen on the set of The Big Broadcast of 1938 (1938), in which Fields was upstaged by rising British comedian, Bob Hope, who earned the studio an Oscar nomination with the song 'Thanks For the Memory'.

With his stock with the studio dropping and his unreliability costing him the title role in Victor Fleming's MGM fantasy, The Wizard of Oz, Fields was teamed with ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy as impecunious circus owner Larsen E. Whipsnade in George Marshall's You Can't Cheat an Honest Man (both 1939). Despite doing decent business, this turned out to be Fields's Paramount swan song and he was forced to accept a co-starring berth with Mae West in the frontier farce, My Little Chickadee. Determined to prove he could succeed outside Paramount, Fields signed to Unviversal for Edward Cline's The Bank Dick (both 1940), in which henpecked nobody Egbert Sousé becomes a hero after accidentally thwarting a robbery.

Having used the pen name Mahatma Kane Jeeves for this late classic, Fields wrote Cline's Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941) as Otis Criblecoblis. Spinning off in random directions from a script that Fields is pitching to Franklin Pangborn at Esoteric Pictures, the action was boldly freewheeling. But the suits lost faith in the project and Fields left the studio to take minor roles in Julien Duvivier's Tales of Manhattan (1942), A. Edward Sutherland's Follow the Boys, S. Sylvan Simon's Song of the Open Road, and Andrew L. Stone's Sensations of 1945 (all 1944).

Orson Welles had hoped to star Fields in an adaptation of The Pickwick Papers. But RKO was nervous after the mixed reception accorded Citizen Kane (1941) and persuaded Welles to make The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) instead. Bergen frequently coaxed Fields on to his radio show and there were rumours that Frank Capra had hoped that Fields would be fit enough to play Uncle Billy in It's a Wonderful Life (1946). However, he died on Christmas Day that year at the age of 66. Like West, he would make the Sgt Pepper cover. So would Karl Marx, but there was no room for Groucho, Chico, and Harpo.

Making Their Marx

The story of the Marx Brothers is strewn with myth-making and misinformation. The brothers were born in New York to Alsace tailor Samuel 'Simon' Marx and his Frisian wife, Minnie Schönberg. But, according to family lore, they got their stage names from vaudeville monologuist Art Fisher, who dealt them out during a poker game in Galesburg, Illinois.

Leonard (b 22 March 1887) was nicknamed Chico because he liked to chase girls, while Adolph (b 23 November 1888) earned the name Harpo through his musical abilities. No one quite knows why Julius (b 2 October 1890) came to be known as Groucho, but aficionados claim it had more to do with the 'grouch' bag that performers used to hide their valuables than either his temperament or a character in the Knocko the Monk comic-strip. Milton (b 23 October 1892) became Gummo either on account of his rubber-soled footwear or because he crept around like a detective (or gumshoe), while Herbert (b 25 February 1901) was later dubbed Zeppo by his siblings, although it's disputed whether the name came from a performing chimpanzee called Mr Zippo or the popular 'Zeke and Zeb' joke about dim-witted Midwesterners.

Although their uncle, Al Shean, was part of the famous Gallagher & Shean variety act, it was far from certain that the brothers would go into show business. Notwithstanding the legend that Gummo played the doll in his Uncle Heinie's ventriloquist act, Chico was the first to appear before an audience, when he started playing piano at nickelodeons, saloons, and dance halls near their Yorkville home. Something of a wayward youth, Chico set a bad example to Harpo, who also tinkled the ivories at the infamous Happy Times Tavern that doubled as a brothel. But the bookish Groucho was so keen to tread the boards after debuting atop a Coney Island beer keg that he begged Minnie to let him work respectively with Leroy's Touring Vaudeville Act, Yorkshire chanteuse Lily Seville, and Gus Edwards' Postal Telegraph Boys before he and Gummo attended Ned Wayburn's College of Vaudeville.

Everything changed, however, when Minnie paired the boys with Mabel O'Donnell in The Three Nightingales in 1907. This tuneful trio morphed into The Six Mascots when Lou Levy replaced Mabel and Harpo reluctantly joined his mother and Aunt Hannah in the family troupe. According to Groucho, they started slipping comedy into their act after he lost patience with an indifferent audience in Nacogdoches, Texas, but there is no evidence to support his yarn. Humour did become the mainstay after Chico participated in the 'Fun in Hi Skule' routine in 1912, although he only became a full-time Marx Brother two years later, when Uncle Al took a hand in their affairs.

It was around this period that the brothers began adopting their trademarx. Chico was already speaking in a cod-Italian accent, but Shean convinced Harpo to drop his Irish brogue and rely on pantomime. He later added the taxi horn and baggy overcoat to his red fright wig, while Groucho hit upon the greasepaint moustache when he arrived late at a theatre too late to paste on fake hair. The cigar and stooping gait similarly owed more to luck than design, although Groucho consciously ditched the German accent used to play the teacher in early skits like 'Hi Skule', 'Mr Green's Reception', and 'Home Again' after the sinking of the Luisitania during the Great War.

Gummo left to become a Doughboy shortly afterwards and was replaced by Zeppo, who took on the straight role in spite of being as gifted a clown as his siblings. Indeed, he was unfazed as Groucho, Chico, and Harpo started improvising business during the musical revues The Cinderella Girl (1918), On the Mezzanine Floor (1921), and I'll Say She Is (1924-25), which took them to Broadway. Here, the success of the George S. Kaufman-scripted shows, The Cocoanuts (1925-26) and Animal Crackers (1928-29), saw them break into movies.

The quartet had appeared in Dick Smith's 1921 silent short, Humor Risk, which parodied Fannie Hurst's bestseller, Humoresque. Sadly, it has not survived, either because the sole copy was accidentally lost or because Groucho torched it. Harpo and Zeppo also featured respectively in Paul Sloane's Too Many Kisses and Frank Tuttle's A Kiss in the Dark (both 1925), but the brothers reunited in the screen versions of The Cocoanuts (1929) and Animal Crackers (1930), which were filmed at Paramount's Astoria Studios in New York.

Directed by Robert Florey and Joseph Santly, the former was set in a Florida hotel run by Mr Hammer (Groucho) and his assistant, Jamison (Zeppo). Harpo and Chico scheme to rob the guests, while Mrs Potter (Margaret Dumont) interferes in the romantic affairs of her daughter, Polly (Mary Eaton). The flimsy narrative was merely an excuse for lots of badinage between Groucho and Chico and Margaret Dumont, as well as for five musical numbers by Irving Berlin.

Victor Heerman took the reins for Animal Crackers, which opens with socialite Mrs Rittenhouse (Dumont) hosting a house party for returned explorer, Captain Jeffrey Spaulding (Groucho), who is assisted by the loyal Horatio Jamison (Zeppo). Signor Emanuel Rivelli (Chico) and The Professor (Harpo) are hired to provide music, but the action turns around the theft of a painting and the chaos that ensues.

Once again, zaniness topped logic. But the primitive sound recording equipment restricted the manic stage antics and it was only when the foursome relocated to Hollywood that they started to recapture their live magic on celluloid. Intriguingly, they kicked off with a six-minute recap of a sketch from I'll Say She Is that was included in The House That Shadows Built (1931), a little-seen 20th anniversary celebration of Paramount Studios. Cinema Paradiso users can, however, see it on Inside the Marx Brothers (2003).

Directed by Norman Z. McLeod (making his solo debut), Monkey Business (1931) was the first Marx vehicle with a wholly original script. Using their adopted monikers, the quartet stowaway aboard a liner and wind up on opposite sides of a gangland stand-off between Big Joe Helton (Rockliffe Fellowes) and Alky Briggs (Harry Woods). So much mayhem ensued that the film was banned in Ireland for fear it would encourage anarchy. Stateside, it made the brothers stars and they featured on the cover of Time Magazine. Groucho and Chico were also given their own radio show, Flywheel, Shyster and Flywheel, which is recalled in the documentary, The Marx Brothers: Radio Days (1934).

McLeod was retained for Horse Feathers (1932), a campus satire that centres around the big football game between Darwin and Huxley colleges. The new principal of the latter, Professor Quincy Adams Wagstaff (Groucho), is convinced by his student son, Frank (Zeppo), to hire professional players to swing the result. But speakeasy iceman Baravelli (Chico) and part-time dog-catcher Pinky (Harpo) are accidentally recruited instead. Woody Allen would name Everyone Says I Love You (1996) after one of the film's songs, while the 'Shipoopi' number in the 'Patriot Games' episode from the fourth season of Family Guy (1999-) takes its inspiration from the picture.

Notwithstanding the ominously shifting situation in Europe following the rise of the Third Reich, Leo McCarey's Duck Soup (1933) parodied diplomatic relations and the corrupting nature of power. Appointed President of Freedonia on the say so of wealthy widow Mrs Gloria Teasdale (Dumont), Rufus T. Firefly (Groucho) and secretary Bob Roland (Zeppo) monitor the activities of Pinky (Harpo) and Chicolini (Chico), who are spies for the neighbouring state of Sylvania. Among the many highlights is the broken mirror scene in which a disguised Harpo precisely matches Groucho's movements. Much imitated by the likes of Norman Wisdom in John Paddy Carstairs's The Square Peg (1959) and Lily Tomlin and Bette Midler in Jim Abrahams's Big Business (1988), the routine was first devised by Harold Lloyd for the 1919 short, The Marathon.

Yet, while Harpo mugged happily and Chico, Groucho, and Margaret Dumont revelled in the absurdist dialogue penned by the likes of S.J. Perelman, Will B. Johnstone, Bert Kalmar, and Harry Ruby, Zeppo came to seem increasingly superfluous as the romantic juvenile and he quit the act to become an inventor and help Gummo run his talent agency. His departure coincided with the expiration of their Paramount contract and Groucho, Chico, and Harpo were lured to MGM by wunderkind producer Irving G. Thalberg. He allowed them to hone on stage the material that would appear in Sam Wood's A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Races (1937). But, while these polished pictures contained some of the best Marx routines, they were hampered by conventional romcom subplots. Moreover, not everyone was as welcoming at the studio and, following Thalberg's tragically early death, the brothers moved to RKO for William A. Seiter's Room Service (1938).

They returned to MGM for Edward Buzzell's At the Circus (1939) and Go West (1940), and Charles Reisner's The Big Store (1941). The first saw Groucho sing the wonderful 'Lydia the Tattooed Lady'. But the trio sensed they were raging against the light and announced their screen retirement. Chico's gambling debts, however, prompted an unscheduled sojourn at United Artists to make Archie Mayo's A Night in Casablanca (1946) and David Butler's Love Happy (1949). There was no grand desire to relive past glories, though. Indeed, each Marx had pursued solo projects at various times during their heyday and even cameoed separately in Irwin Allen's The Story of Mankind (1957). By this time, Groucho had reinvented himself as the host of the TV quiz, You Bet Your Life (1947-61), and as a chat show guest, viz The Dick Cavett Show: Comic Legends (2006).

He also continued to make the odd film, most notably Irving Cummings's Double Dynamite (1951), Chester Erskine's A Girl in Every Port (1952), Frank Tashlin's Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1967), Otto Preminger's Skidoo (1968), and Michael Ritchie's The Candidate (1972). Moreover, Groucho co-starred with Chico in the 1957 short, Showdown At Ulcer Gulch, and guested in Harpo and Chico's General Electric Theatre outing, 'The Incredible Jewel Robbery', and their short-lived series Deputy Seraph (both 1959). However, Billy Wilder's hopes of reuniting the threesome in the tentatively titled A Day At the UN were dashed when Chico died in 1961.

Harpo followed three years later, while Groucho passed away four months after Gummo in 1977. Zeppo lived another two years. But the joy generated by the Marx Brothers' inspired lunacy will surely last forever and all Cinema Paradiso users have to do to access it is click.

-

Monkey Business / Horse Feathers (1932)

2h 15min2h 15min

2h 15min2h 15minOver a dozen writers laboured over five months on the first comedy the Marx Brothers made in Hollywood. Stowing away on a liner, they become mixed up with rival mobsters, with Groucho turning on the charm with moll Thelma Todd.

- Director:

- Norman Z. McLeod

- Cast:

- Maurice Chevalier, Groucho Marx, Chico Marx

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Music & Musicals, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Trouble in Paradise (1932) aka: The Golden Widow / The Honest Finder / Thieves and Lovers

1h 23min1h 23min

1h 23min1h 23minNowhere is Ernst Lubitsch's iconic 'touch' more readily evident than in this deliciously sly romantic comedy, which mocks the manners and mores of the elite by focussing on the machinations of thieves Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins in fleecing perfume heiress Kay Francis.

- Director:

- Ernst Lubitsch

- Cast:

- Miriam Hopkins, Kay Francis, Herbert Marshall

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Horse Feathers (1932)

Play trailer1h 3minPlay trailer1h 3min

Play trailer1h 3minPlay trailer1h 3minRecycling gags from the 'Fun in Hi Skule' stage sketch, this Marx romp hurtles at breakneck speed before climaxing with a knockabout football match. Sadly, a number of scenes (including those featuring college widow, Thelma Todd) were cut by the censor and have been lost forever.

- Director:

- Norman Z. McLeod

- Cast:

- Groucho Marx, Chico Marx, Harpo Marx

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

She Done Him Wrong (1933) aka: Diamond Lil / Ruby Red / Diamond Lady / Diamonds / Lady Lou

1h 2min1h 2min

1h 2min1h 2minThere was invariably a prototype feminist message beneath the saucy shenanigans in a Mae West film. She also ensured that Black maids like Louise Beavers's Pearl in this 1890s Bowery saloon saga were shown to be confidantes rather than mere servants.

- Director:

- Lowell Sherman

- Cast:

- Mae West, Cary Grant, Owen Moore

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Drama, Music & Musicals, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Marx Brothers: Duck Soup (1933)

Play trailer1h 5minPlay trailer1h 5min

Play trailer1h 5minPlay trailer1h 5minFreednonian president Groucho wants a quick victory in this diplomatic lampoon, as he's rented the battlefield by the hour. Even though Benito Mussolini was so offended that he banned the film in Italy, contemporary critics were sceptical about what is now considered a masterpiece.

- Director:

- Leo McCarey

- Cast:

- Groucho Marx, Harpo Marx, Chico Marx

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Music & Musicals

- Formats:

-

-

I'm No Angel (1933)

Play trailer1h 24minPlay trailer1h 24min

Play trailer1h 24minPlay trailer1h 24minFamed for her one-liners, West was on fine form in this pop at straight-laced morality set against a circus backdrop. 'When I'm good I'm very good', Tira says at one point. 'But when I'm bad I'm better.' Surprisingly the Hays Office went easy on West on this occasion, but they were already sharpening their pens.

- Director:

- Wesley Ruggles

- Cast:

- Mae West, Cary Grant, Gregory Ratoff

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Music & Musicals, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

W.C. Fields: The Old Fashioned Way / Poppy (1936)

2h 18min2h 18min

2h 18min2h 18minHaving attended a revival of the classic temperance play, The Drunkard, in Los Angeles, W.C. Fields decided to incorporate it into this story of an itinerant theatrical troupe in order to cheer up Depression audiences by poking fun at his own bibulous reputation.

- Director:

- William Beaudine

- Cast:

- W.C. Fields, Rochelle Hudson, Richard Cromwell

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

Belle of the Nineties (1934)

Play trailer1h 10minPlay trailer1h 10min

Play trailer1h 10minPlay trailer1h 10minWest went south in this period comedy, in which she takes up an offer to sing at the Sensation House owned by the scheming John Miljan. However, boxer beau Roger Pryor fetches up in New Orleans and saves the day when things begin to heat up.

- Director:

- Leo McCarey

- Cast:

- Mae West, Roger Pryor, Johnny Mack Brown

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Music & Musicals

- Formats:

-

-

W.C. Fields: It's a Gift (1934)

1h 5min1h 5min

1h 5min1h 5minFields drew on trusted stage sketches like 'The Picnic', 'A Joy Ride', and 'The Back Porch' for this cockeyed chronicle of a family man who believes the entire universe is conspiring against him after he quits his grocery store for a California orange ranch.

- Director:

- Norman Z. McLeod

- Cast:

- W.C. Fields, Kathleen Howard, Jean Rouverol

- Genre:

- Classics

- Formats:

-

-

W.C. Fields: You're Telling Me! / Man on the Flying Trapeze (1935)

2h 6min2h 6min

2h 6min2h 6minDomestic bliss curdles once again for W.C. Fields, as his hopes of attending a wrestling match are dashed by rumours spreading around town that mother-in-law Vera Lewis has succumbed to poisoned liquor. Look out for Carlotta Monti as Fields's secretary.

- Director:

- Erle C. Kenton

- Cast:

- W.C. Fields, Joan Marsh, Buster Crabbe

- Genre:

- Comedy, Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Bluebeard's 8th Wife (1938) aka: Bluebeard's Eighth Wife

Play trailer1h 26minPlay trailer1h 26min

Play trailer1h 26minPlay trailer1h 26minMuch-married Gary Cooper can't understand new bride Claudette Colbert's insistence on keeping her distance in this suggestive screwball. Scripted by Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder, Lubitsch's last picture for Paramount points towards its comic future in the snarkier 1940s.

- Director:

- Ernst Lubitsch

- Cast:

- Claudette Colbert, Gary Cooper, Edward Everett Horton

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Romance

- Formats:

-