This year marks the 70th anniversary of the release of John Halas and Joy Batchelor's animated adaptation of George Orwell's Animal Farm. Cinema Paradiso recalls the making of the film and the legacy of British animation's power couple.

Among the many excellent events at the 2024 Brighton Animation Festival are two celebrations of the life and work of John Halas and Joy Batchelor. Daughter Vivien Halas has spent the last four decades maintaining the legacy of her parents and her presentation about their career will be followed by a special screening of their best-known work, Animal Farm (1954).

Cinema Paradiso users can order the film with the click of a mouse, while they can also learn more about the team from the extras contained in The Halas & Batchelor Short Film Collection (2015), which is available to rent on high-quality DVD and Blu-ray. In the article below, the hyperlinked H&B shorts can be found on this considered selection, which doesn't quite run for the 38 hours and 45 minutes promised on Amazon!

The Blair Farm Project

Written during the Second World War, when Britain was allied with the Soviet Union in the fight against the fascist Axis, George Orwell's Animal Farm was published on 17 August 1945. Reluctant to offend the Kremlin, Orwell's regular publisher, Victor Gollancz, turned down a satire that was openly critical of Joseph Stalin and Faber & Faber and Jonathan Cape followed suit before Secker & Warburg stepped into the breach.

Having witnessed the struggles during the Spanish Civil War between the Communists loyal to Stalin and the POUM forces who owed allegiance to Leon Trotsky, Orwell (whose real name was Eric Blair) was keen to remind readers about the Purges of the 1930s and what he felt had been the betrayal of the 1917 Revolution that had overthrown the Romanov monarchy. In his 1946 essay, 'Why I Write', Orwell had claimed, 'Animal Farm was the first book in which I tried, with full consciousness of what I was doing, to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole.'

This wasn't the first book about animals fighting back against humans, however. In 1880, Russian author Nikolai Kostomarov had written Skotskoi Bunt, which translates as The Revolt of the Farm Animals. It was left on the shelf until 1917, when it appeared posthumously as a serial in Niva magazine, just a few months before the outbreak of the revolution depicted by Sergei Eisenstein in October (1928). Four years earlier, as the master montagist was making Strike (1924), Polish Nobel laureate Wladyslaw Reymont had published, Bunt, which used barnyard animals to parody the Bolshevik coup. The film adaptations of two of Reymont's novels are available from Cinema Paradiso in the form of Andrzej Wajda's The Promised Land (1974) and The Peasants (2023), which was animated by DK and Hugh Weichman from 40,000 oil paintings.

Orwell's story is set on Manor Farm, which has been badly neglected by the alcoholic Mr Jones. One night, Old Major the boar summons the other animals to a meeting in the barn. He claims that it's an injustice that the produce of their labour is taken away from them to profit an undeserving boss. Consequently, the creatures should rise up and run the farm as a collective that benefits them all.

Shortly after Old Major's death, ambitious pigs Snowball and Napoleon lead a revolution that turfs out Mr Jones and sees his property renamed, 'Animal Farm'. At Snowball's behest, the Seven Commandments of Animalism are painted on the side of the barn, the last of which reads, 'All Animals Are Equal'.

For a while, the farm prospers. Snowball teaches the other animals to read and write and introduces a plan to share tasks and improve yields. Boxer the carthorse and Benjamin the donkey work harder than most, while Napoleon does little other than train the puppies left by a sheepdog killed in the uprising. He even cowers away when his fellow beasts rally to repel an attempt by Mr Jones to reclaim control. But Napoleon is merely biding his time and, when Snowball suggests the construction of a windmill, he orders the dogs to drive Snowball away.

Abetted by the sycophantic Squealer, Napoleon proceeds to dispense with the communal meetings that his predecessor had introduced and starts issuing dictatorial commands. When some of the animals grumble about his methods, Napoleon declares that Snowball had been in league with Mr Jones and purges the population of those animals he claims to be undermining the enterprise that he now embodies - hence the amended slogan: 'All Animals Are Equal - But Some Are More Equal Than Others.'

The windmill is destroyed by an act of sabotage, while Boxer is injured in fighting off a second bid to occupy the farm. When he is hurt by a falling block while rebuilding the windmill, Napoleon arranges for him to be taken to the knacker's yard and Snowball convinces the others that the van was actually an ambulance from the animal hospital.

Time passes and the animals give up on the grand promises that Napoleon had made when he came to power. He now walks around the renamed 'Manor Farm' on his hind legs, breaking another Commandment: 'Four legs good, two legs bad.' Indeed, he also wears clothes, sleeps on a bed, and drinks whisky with the local farmers, who have come to accept him. As the narrative ends, however, Napoleon and Mr Pilkington square off when they each play the ace of spades during a drunken game of cards.

Stalin was to outlive Orwell, who died on 21 January 1950 at the age of 46. Almost immediately, plans were hatched to bring Animal Farm to the screen. The subject matter meant that Walt Disney was not an option. But who would be capable of tackling such a tricky text with integrity and innovation?

Enter John and Joy

While Orwell was writing his anthropomorphical masterpiece, the animating duo of John Halas and Joy Batchelor were making commercials for cinemas and doing their bit for the war effort by producing public information and military training films for the Ministry of Information and other establishment bodies.

Born in Budapest on 16 April 1912, János Halász was the seventh son of a Catholic father and a Jewish mother. Decamping to Paris as a teenager, he had published cartoons in various magazines before returning to the Hungarian capital in 1927 to serve his animation apprenticeship with George Pal. He taught Halász how to use a camera and time action, as well as how to work with paper cutouts and puppets. Some of Pal's early work can be found on Volumes One and Four of Retour de Flamme, while Cinema Paradiso users can also order some of the Hollywood features that Pal both produced - Irving Pichel's Destination Moon (1950), Rudolph Maté's When Worlds Collide (1951), George Marshall's Houdini, and Byron Haskin's The War of the Worlds (both 1953) - and directed, The Time Machine (1960).

In 1930, Halász went to study typography and poster design under Sandor Bortnyik and László Moholy-Nagy at the Muhely Academy, which was nicknamed 'the Hungarian Bauhaus'. Two years later, he joined forces with Gyula Macskássy and Félix Kassowitz to launch Hungary's first animation studio, Coloriton, which branched out from beer and cigarette commercials to make The Treasure of the Joyful King (1934). Commissions were scarce, however, and when a design job in Paris turned out to involve selling salami, Halász jumped at the chance to open an animation studio in London. It was here that he met the love of his life in 1936.

Born in Watford on 12 May 1914, Joy Ethel Batchelor was the oldest of three children sired by Edward Batchelor, a lithographic draughtsman who passed on his talent for drawing. Mother Ethel suffered a nervous breakdown after the death of Joy's four year-old brother and frequently locked her in a cupboard under the stairs, where she made up stories in order to 'escape, shine, and be different'. Following a scholarship to the Watford School of Art, Batchelor was offered the chance to study at the prestigious Slade School of Art in London, but her family needed her to start bringing home an income.

Quitting a tedious job painting keepsakes on a factory production line, Batchelor joined British Cartoons, where she assisted Roland Davies on a series about Steve the talking carthorse. In 1934, she started working as an inbetweener at Dennis Connelly's animation studio. Initially bored and critical of the process, Batchelor was disappointed when the studio closed and turned to designing posters for a silkscreen printer. She was keen to return to animation, however, and answered an Evening Standard ad for experienced animators to work on Music Man at British Animated Films. The director was János Halász and a 50-year partnership started when production moved to Budapest in order to keep down costs. Nevertheless, this 1938 short still counts as Britain's first Technicolor cartoon and it was praised for its technical quality and 'a certain amount of charm' by Today's Cinema.

As war clouds were already beginning to gather over Europe, the pair returned to London in June 1938 to found British Colour Cartoon Films. They also opened a graphic design studio off The Strand, where Halász illustrated children's books and drew cartoons for Lilliput magazine. As he still spoke little English, Batchelor acted as a go-between with clients. She also contributed drawings to newspapers and magazines like Harper's Bazaar, Queen, and Vogue, while also illustrating cookbooks and it's worth noting that her brand of character design would become the Halas & Batchelor house style.

Also now based in London, George Pal introduced them to Alexander Mackendrick, who was a designer and producer at the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency. As film stock was not rationed during the war, cinema commercials became popular and Halas & Batchelor Cartoon Films was founded in May 1940 as an independent subsidiary of JWT. Despite not believing in the institution, the couple had married on 27 April in order to prevent the newly named Halas from being interned on the Isle of Man as an enemy alien. By becoming his wife, however, Batchelor had her British citizenship revoked and she was classified as a 'friendly enemy alien' and subjected to strict curfews until her rights were restored on 28 December 1945 - which just happened to be the 50th anniversary of the first projected film show given to a paying audience by Louis and Auguste Lumière.

Regardless of their treatment, Halas and Batchelor made 70 films over the next four years from their studio at 10A Soho Square. They even survived a direct hit on their Chelsea flat in 1941, which left Batchelor with lifelong health issues after she was buried up to her neck in rubble. As he was under a doorway, Halas emerged unscathed. When not producing propaganda, the pair made commercials like Carnival in the Clothes Cupboard (1941) and The Fable of the Fabrics (1942) for Lux, which were scripted by Alexander Mackendrick, who would become a major force at Ealing Studios with Whisky Galore! (1949), The Man in the White Suit (1951), Mandy (1952), The Maggie (1953), and The Ladykillers (1955) before having mixed independent fortures with Sweet Smell of Success (1957), Sammy Going South (1963), and A High Wind in Jamaica (1965) - all of which are available to rent from Cinema Paradiso.

During her stint as a freelancer, Batchelor had worked for Shell. So, when Jack Beddington, the company's publicity director, became head of the Ministry of Information's film division, he ensured that Halas & Batchelor were kept busy via a connection with Realist Films. As Halas recalled: 'For the work load we would have needed 20 to 30 staff. We had only 7. It meant that it was work day and night. Scripts and storyboards at night and the physical execution of the film by day. We put the studio in motion in the middle of 1941, badly equipped with an old French stop-motion camera made by Eclair costing five pounds.'

Among the dependables who helped H&B hit its deadlines were animators Wally Crook, Vera Linnecar, Harold Mack, and Kathleen 'Spud' Murphy, while Francis Chagrin provided the music. Batchelor was in charge of layout, characters, and storyboards, while Halas was responsible for tracing and painting, as well as shooting and editing, and the overall management of the studio. They worked together on the screenplays and direction. In 1980, Halas described the war years in a three-part interview with Chris Kelly for the excellent children's film programme, Clapperboard (1972-82), which can be found among the extras of The Halas & Batchelor Short Film Collection.

What makes these shows so valuable is that they contain clips of several propaganda films. You can also seek out the likes of the BFI's Ration Books and Rabbit Pies: Films From the Home Front (2016) for such classics as Dustbin Parade (1942), in which a discarded bone fulfils a dream to become a bomb that will be dropped on Germany. But you'll have to go scouring the BFI and Imperial War Museum websites (where they are available to view for free) for titles like Filling the Gap (1942), which encouraged people to grow vegetables on allotments; the self-explanatory Compost Heaps, which featured the BBC radio gardening expert, C.H. Middleton; Early Digging (both 1943) about avoiding frosts; Cold Comfort, which advised on saving electricity; From Rags to Stitches, which centred on the making of nurses' uniforms; Mrs Sew and Sew (all 1944), which offered mend and make do tips; Tommy's Double Trouble, which described the symptoms of foot rot; and Six Little Jungle Boys (both 1945), which reminded troops in the Far East about the dangers of venereal diseases.

A series of four Arabic shorts - Abu's Dungeon, Abu's Poisoned Well, Abu's Harvest, and Abu Builds a Dam (all 1943) - were only shown in the Middle East, while the Admiralty commissioned the company's first feature, Handling Ships (1945), an instructional film about steering that remained in use for decades. The Home Office would later get value for money out of a second featurette, Water For Fire Fighting (1948).

Having given birth to Vivien and Paul in 1945 and 1949 respectively, Batchelor started to work more regularly from home. But the studio remained as busy as ever, as the Clement Attlee government celebrated by Ken Loach in The Spirit of '45 (2013) commissioned films about public health, such as Fly About the House and A Mortal Shock (both 1950). As the Welfare State legislation was rolled out, H&B were there to explain and reassure in a cartoon series about an everyman named Charley, who was voiced by comedian Harold Berens. Providing a vital insight into the postwar mindset, Charley's March of Time, Charley in the New Schools, Charley's Black Magic, Robinson Charley, and Farmer Charley were made in consultation with the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Stafford Cripps. But, as Home Secretary Herbert Morrison resembled Charley, Sir Winston Churchill took great pleasure in calling him 'a right Charley' whenever he got the opportunity.

Produced in 1946, the first two entries, Charley in New Town and Charley in 'Your Very Good Health' can be found among the extras accompanying Basil Dearden's They Came to a City (1944), while Charley's Junior School Days (1949) can be found on the BFI's Central Office of Information Collection: Vol.8: Your Children and You (2013). As his homeland disappeared behind the Iron Curtain, Halas also made a point of making Cold War offerings such as The Shoemaker and the Hatter (1949), which examined the recovery of Europe through the Marshall Plan. This may well have found itself on the same bill as George Seaton's Berlin aid-drop saga, The Big Lift (1950). Such was the diversity of H&B's projects, however, that they could slot into any programme, as they tackled such world about us topics as oil (As Old As the Hills, 1950) the history of motoring (Moving Spirit, 1951), tanker shipping (We've Come a Long Way, 1952), and aviation (Power to Fly, 1953).

But Halas wasn't just interested in showing how animation and actuality could intermingle. He was also determined to develop the artistry of the form and collaborated with two compatriots, designer Peter Foldes and composer Mátyás Seiber, to craft the abstract piece, The Magic Canvas (1948), as an experiment in conjuring the essence of freedom. During the Festival of Britain, Halas also collaborated with the British Film Institute on the 'Poet and Painter' series that edited together rostrum camera moves to illustrate verses like William Shakespeare's 'Spring and Winter' and William Cowper's 'John Gilpin'. The latter was designed by Ronald Searle, whose illustrations would become familiar to film-goers through the opening credits to Frank Launder's The Belles of St Trinian's (1954) and Blue Murder At St Trinian's (1957) and Sidney Gilliat's The Great St Trinian's Train Robbery (1966), which were inspired by Searle's comic strips. Always keen to try out new technology, Halas also made Britain's first 3-D short, an adaptation of Edward Lear's The Owl and the Pussycat (1952), which he followed with the puppet animation, The Figurehead (1953), which was inspired by a poem by Crosbie Garston.

H&B now had competition from Gaumont British Animation, which J. Arthur Rank had opened to create cartoon content for his Gaumont and Odeon cinemas. He hired David Hand - who had directed the Walt Disney trio of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Dumbo (1940), and Bambi (1942) - to supervise the Animaland and Musical Paintbox series. Hand also produced a number of adverts, around the time that H&B were making Train Trouble and Radio Ructions for Kellogg's, Good King Wenceslas for Rinso, Oxo Parade for Oxo, What's Cooking? for Bovril, The Flu-ing Squad for Aspro, and Polly Put the Kettle On for Brooke Bond Tea. But, when Hand tried to raise funds to adapt features from H.G. Wells's The First Men in the Moon and Lewis Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark, he found the task impossible. Nobody, it seemed, was willing to invest in British animated features.

Weaponising Cinema

Postwar Hollywood was a hotbed of clashing ideologies and intrigue. During the war, the studios had been asked to produce pro-Soviet pictures in order to show solidarity with America's ally. Paramount was the only studio to duck the task, as Fedor Ozep and Henry S. Kesler's Three Russian Girls, Michael Curtiz's Mission to Moscow, Sidney Salkow and Tay Garnett's The Boy From Stalingrad (all 1943), Jacques Tourneur's Days of Glory, Gregory Ratoff's Song of Russia (both 1944), and Zoltan Korda's Counter-Attack (1945) went on general release across the United States. Frank Capra and Anatole Litvak added Battle of Russia (1943) to their hugely influential 'Why We Fight' series (1943-45), while Lewis Milestone's The North Star (1943) was nominated for six Academy Awards. Even in Britain, a Soviet sharpshooter was a feted in Bernard Miles and Charles Saunders's wonderful rustic drama, Tawny Pipit (1944).

As soon as the Cold War set in, however, the studios distanced themselves from such flagwavers and permitted Senator Joseph McCarthy to conduct hearings of the House UnAmerican Activities Committee in Hollywood from 1947. This Red Scare period is recalled in such films as Martin Ritt's The Front (1976), Philip Saville's Fellow Traveller (1989), Karl Francis's One of the Hollywood Ten (2000), and Jay Roach's Trumbo (2015). Eradicating the threat of Communism through the introduction of a blacklist wasn't enough, however. Inspired by a 1943 memo for the Office of Strategic Services on 'Motion Pictures as Weapons of Psychological Warfare', the Psychological Strategy Board in Washington became actively engaged in persuading the studio chiefs to shape the messages contained in their movies.

Under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, speechwriter Charles Douglas Jackson was in active contact with Luigi Luraschi, a sleeper contact who was Head of Foreign & Domestic Censorship at Paramount. He advised the CIA that it should use the Production Code Administration to weed out any anti-American or pro-Communist inferences in screenplays. Luraschi also suggested that films should present an idealised version of daily life to counter any Kremlin claims of disharmony within American society. Consequently, Hollywood painted a false picture of race relations in the postwar period, as well as the social issues that had been presented in so-called 'problem pictures' like Billy Wilder's The Lost Weekend (1945).

Hollywood was coaxed into portraying the USA as a good neighbour to Latin America and a non-imperialist partner to the countries of the Developing World. Moreover, the studios were asked to present anti-Communist propaganda as entertainment in such features as Gordon Douglas's Walk a Crooked Mile (1948) and I Was a Communist For the FBI (1951), Robert Stevenson's The Woman on Pier 13, R.G. Springsteen's The Red Menace (both 1949), and Edward Dmytryk's My Son John (1952). Louis De Rochemont, whose March of Time newsreel had been parodied by Orson Welles at the start of Citizen Kane (1941), also produced Alfred L. Werker's alarmist Walk East On Beacon (1952) and he was to play a key role in bringing Animal Farm to the screen.

One of Luraschi's colleagues at Paramount was producer Carleton Alsop, who was in regular contact with CIA operative E. Howard Hunt. He would later achieve notoriety through the Watergate break-in and has been played on screen by Ed Harris in Oliver Stone's Nixon (1995), Daniel Jenkins in Martin Scorsese's The Irishman (2019), J.C. MacKenzie in Gaslit (2022), and Woody Harrelson in White House Plumbers (2023). Back in 1950, Hunt was working for the CIA's Psychological Warfare Workshop and he approached Alsop to secure the screen rights to Animal Farm from Orwell's widow, Sonia, as the novel's anti-Stalinist message appealed to the Agency's Office of Policy Coordination. Alsop travelled to Britain with writer Finis Farr to convince Sonia to entrust them with project rather than either the US Army or the producers of the Woody Woodpecker cartoons, who had also expressed an interest in the text.

According to some sources, Sonia agreed to a £5000 deal on the proviso that she could meet her hero, Clark Gable. However, this seems to have been a rumour. What is true, though, is that Hunt selected De Rochemont to produce the picture because he had worked for him at March of Time. Furthermore, De Rochemont had supervised Henry Hathaway's The House on 92nd Street (1945) and 13 Rue Madeleine (1947), which had respectively lionised the wartime operations of the FBI and the OSS. Realising that the material would have to be animated, De Rochement opted against awarding the contract to Walt Disney, as his studio had been having union difficulties (which had resulted in the formation of United Productions of America), while the various in-house studio animation units were too busy to take on such a large-scale enterprise.

As De Rochement had frozen box-office receipts in Britain, where production costs were considerably cheaper, he cast an eye across the Atlantic. During the war, he had worked with writers Philip Stapp and Lothear Wolf at the US Navy film unit. They had got to know Joy Batchelor during the making of The Shoemaker and the Hatter and they recommended H&B to De Rochement. As a consequence, Stapp and Wolf were hired to work on the screenplay with Halas and Batchelor and Borden Mace, who had collaborated with De Rochment on Alfred Werker's groundbreaking race drama, Lost Boundaries (1949).

Hunt first revealed the CIA's involvement in his autobiography, Undercover: Memoirs of an American Secret Agent (1974). Subsequently, academics Frances Stonor Saunders, Tony Shaw, and Daniel Leab have all sought to follow the paper trail. But it genuinely seems as though Halas and Batchelor had no idea that they were being used as political pawns in the production of anti-Communist propaganda.

Orwell That Ends Well?

Although Halas and Batchelor were actively engaged in the writing of the screenplay of Animal Farm, they had to endure nine rewrites before their paymasters were entirely satisfied. Cosmetic changes included the downplaying of the significance of dogs Jessie and Bluebell and the creation of Mr Whymper to supply jams and hooch to the pigs in return for farm produce. But Orwell's pessimistic ending proved a problem for the CIA, who disliked the idea of the pigs and humans being in evil cahoots. Consequently, they insisted on a new denouement that saw the animals rise up to overthrow their oppressors in a show of communal power that could be equated with democracy. This version chimed in with the vision of CIA director Allen Dulles and his brother, John Foster Dulles, who was Eisenhower's Secretary of State and had recommended combatting Communism rather than following President Harry S. Truman's policy of containment.

In later interviews, Halas maintained that he had been happy with the change, as it had removed any ambiguity over the human-porcine alliance and posited the notion of perpetual revolution, which he felt to be optimistic. He also insisted that he wasn't a particularly political person and was more interested in meeting the aesthetic and technical challenges posed by material that was quite clearly aimed at adults rather than children. What's more, H&B had to satisfy Orwell's publisher, although it helped that Fredric Secker had links with MI6, which further reinforced the production's connection with the murky world of espionage.

Secker seemingly suggested that Old Major spoke in a Churchillian manner, but had no overt objections to the revised conclusion. However, the debates rumbled on into the spring of 1951, after Halas and Batchelor had returned from spending several weeks working on storyboards in St Tropez. The CIA was concerned that American farmers would take exception to the depiction of the neighbours. So, only Mr Jones was presented as a bad egg, while the animals on other farms were shown to be reasonably content with their lots.

The CIA consensus was also that Snowball was too sympathetic and De Rochement sent a memo to Halas and Batchelor demanding that he be presented as a 'fanatic intellectual whose plans if carried through would have led to disaster no less complete than under Napoleon'. A proposed scene showing how Snowball was tracked down to exile and slaughtered by Napoleon's canine lackeys was also nixed, as it was deemed to resemble too closely the 1940 murder in Mexico City that Joseph Losey would later reconstruct in The Assassination of Trotsky (1972).

In order to handle a commission of this size, H&B hired around 80 animators, many of whom had just been released by Gaumont British, including John Reed, who had been David Hand's assistant. Regular trips were made to working farms to research animal locomotion and the layout of buildings. Batchelor was involved in the character design and storyboarding, as well as in the drawing up of 'tension charts', which detailed how colour, lighting, and even music was to be used in a particular scene.

Much of the animation drawing and the compositing of the cels was done in London, as Halas insisted on checking that the inked and painted cels lined up precisely with the backgrounds. The actual photography took place in Gloucestershire. In all, 300,000 staff hours and two tons of paint were required to create the 250,000 drawings and 1800 coloured backgrounds needed for the 75-minute running time. According to art expert Carien van Aubel, 'There's a huge amount of drawings needed for each frame, as every character movement demands individual sketches.'

'Several animators would work on one specific task,' Van Aubel revealed. 'The outlines are always drawn on the front by one person, and the characters are then painted on the reverse by another person.' The backgrounds were flattened to focus attention on the animals, who were given bits of comic business or recurring traits to ensure that the audience identified with them. The creatures also had to carry much of the story's symbolism and caricature was employed in the depiction of the pigs to highlight the growing pomposity that suggested the increasingly human nature of their behaviour.

Attention was lavished on every detail. 'The animals often have their typical coat and skin colours,' Van Aubel explained, 'but there are variations for the more important characters. A clear contrast of the animals is created by placing them in front of the more washed colours of the background.' As she continued, 'The facial expression of all the animals comes from human expressions. The animators used their own facial impressions by acting them out in front of the mirror and applied them to the animals.'

The personalities of the different beasts were refined by Maurice Denham, who did the voices and the noises for every single character. Living to be 92, Denham was a wonderful actor and Cinema Paradiso users can sample delights from across his career by exploring from the Searchline. But we should point out Robert Parrish's The Purple Plain (1954), for which he was nominated for the BAFTA for Best Actor; Robert Days Two-Way Stretch (1960), in which he plays the prison governor; and David Jones's 84 Charing Cross Road (1987), in which he genially potters around Anthony Hopkins's bookshop.

A student of Béla Bartók, Mátyás Seiber heightened the drama and satire alike with a dexterous score that also included the song that the animals sing around the campfire in the farmyard. The lyrics fashioned by Orwell were replaced by the braying, squealing, and squawking of the animals to reinforce their sense of liberty, while also showing how harmony can be reached from different languages. It was one of many inspired touches that have ensured that Animal Farm has remained timeless in a way that is not always the case with contemporaneous non-Disney feature animations.

Ironically, Joseph Stalin died during production, which was finally completed in April 1954. The CIA money pot also expired before H&B could sign off the last layout and De Rochemont had to dip into his own pocket in order to bail them out. But such generosity came at a price and ensured that the CIA got the amended ending that had been resisted for so long.

More Equal Than Others

Having cost three times its initial £92,790 budget and missed its 15 May 1953 completion date by over a year, Animal Farm premiered at the Paris Theatre in Manhattan on 29 December 1954. A gala reception followed at the headquarters of the United Nations. At the British launch at The Dorchester Hotel, guests were treated to an Animal Farm cocktail, which was basically

White Horse scotch with a celery, cucumber, and carrot garnish.

The reviews were enthusiastic, with one American paper using the headline, 'The British out-Disney Disney'. Several critics deplored the revised ending, however, with one opining, 'Orwell would not have liked this one change, with its substitution of commonplace propaganda for his own reticent, melancholy satire.' In order to entice viewers, animator Harold Whitaker reworked the story for a comic strip that ran in several regional newspapers. The British government also sponsored a strip for publication in East Africa, Brazil, Mexico, Venezuela, Burma, Thailand, and India.

But the box-office returns were disappointing and it took 15 years for the producers to make back their money. This clearly put paid to any planned collaborations with De Rochemont, including Batchelor's dream project based on the 12th-century poems of Marie de France. However, Animal Farm was seen by thousands of schoolchildren before it found its way on to television and the various home entertainment formats. Such was its cachet that an image of Benjamin watching Napoleon pontificating from a platform adorned the sleeve 'English Civil War', a 1979 single by The Clash.

Undaunted by the commercial failure of their masterpiece, Halas and Batchelor continued to innovate. He produced the animated bridging sequences for the widescreen extravaganza, Cinerama Holiday (1955), before anticipating the prehistoric theme of Hanna-Barbera's The Flintstones (1960-66) with The World of Little Ig (1956), which centred on the adventures of a caveboy. The misuses to which the motion picture had been put were satirised in History of the Cinema (1957), while Automania 2000 (1963) imagined a future in which there were so many cars on the road that people had to live in them because they were gridlocked. Also produced during this period were Hamilton the Musical Elephant (1961), with a jazz score by John Dankworth; a bid to solve the dog bathing conundrum, Flow Diagram (1966); and the wittily scathing existential quest, The Question (1967).

The benefits and dangers of television came under scrutiny in For Better For Worse (1959). Yet H&B still became the first British animator to produce for the small screen, with series like Habatales (1956), Foo-Foo (1960), Snip and Snap (1961), and Dodo the Kid From Outer Space (1965), which was the company's first foray into colour television. Particularly memorable was the seven-part BBC series, Tales From Hoffnung (1965), which included the hilarious 'The Hoffnung Symphony Orchestra' and 'Birds Bees and Storks', for which Peter Sellers voiced a bashful professor mumblingly ruminating on the facts of life.

In 1960, the duo set up the Educational Film Centre to produce 8mm shorts, including the language teaching trio of The Carters of Greenwood, Martian in Moscow, and Les Aventures de la famille Carré (all 1964). Ever the innovator, Halas also devised the 'Living Screen' animation technique that he used for a 1963 travelling show entitled, Is There Intelligent Life on Earth? He also had a go at directing a live-action feature, The Monster of Highgate Ponds (1961), which was aimed at Saturday matinee audiences and can be rented from Cinema Paradiso on the BFI's third Children's Film Foundation collection, Weird Adventures (2013).

Batchelor wrote the story for this cheap and cheerful offering that boasts some very homemade-looking creature effects. However, struggles with her health and alcohol meant that she tended to work from home, leaving Halas free rein at the studio. He became a founder member and the longtime president of the International Animated Film Association (1960-85), doing much to promote animation from all parts of the planet. Yet H&B remained a team effort, even though Batchelor took a solo directing credit on an adaptation of Gilbert and Sullivan's Ruddigore (1966), which was hailed as the first cartoon operetta.

In order to keep the studio afloat, Halas sold some shares to Tyne Tees Television and picked up contracts for such outsourced Hanna-Barbera shows as The Addams Family, The Jackson Five (both 1972), and The Osmonds (1973). The studio also helped out on René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo's The Twelve Tasks of Asterix (1976) before Halas completed his final feature, Max and Moritz (1977), which celebrated the life of comic-strip pioneer, Wilhelm Busch. He also moved into music videos, with Butterfly Ball (1976) for Roger Glover and Autobahn (1979) for Kraftwerk.

Having teamed with Hungarian artist János Kass for a computer-animated disquisition on humankind's wasted potential in Dilemma (1981), Halas explored the work of Leonardo Da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec in Great Masters (1985). This was followed by the equally admired BBC series, The Masters of Animation (1987), which really should be available on disc.

After long service to the London International Film School, Batchelor died on 14 May 1991. Halas continued working, notably teaming on Know Your Europeans UK (1995) with Bob Godfrey, the creator of such animated gems as Roobarb (1974) and Henry's Cat (1983-93). Halas passed away at the age of 82 on 21 January 1995. Let's hope the Animal Farm anniversary generates sufficient renewed interest in H&B for some of their wartime and television work to be collected on disc. Britain hasn't produced animators as proficient or prolific since and the names Halas and Batchelor deserve to be as well known here as Disney.

-

Walk East on Beacon (1952) aka: The Crime of the Century / Louis de Rochemont's Walk East on Beacon!

1h 36min1h 36min

1h 36min1h 36minBased on a Reader's Digest article by J. Edgar Hoover and designed show off FBI techniques, Alfred L. Werker's docu-thriller follows Federal agent George Murphy, as he teams with the US Coast Guard to find the Soviet spy who is leaking secrets and blackmailing space-weapons scientist Finlay Currie.

- Director:

- Alfred L. Werker

- Cast:

- George Murphy, Finlay Currie, Virginia Gilmore

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Drama, Classics, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

The Assassination of Trotsky (1972) aka: Das Mädchen und der Mörder - Die Ermordung Trotzkis

1h 40min1h 40min

1h 40min1h 40minSet in Mexico City in 1940, Joseph Losey's drama shows how Leon Trotsky (Richard Burton) and wife Natalia Sedowa (Valentina Cortese) survive an assassination attempt, only to be targeted by banished Stalinist Frank Jacson (Alain Delon), who is holed up in a hotel room with translator Gita Samuels (Romy Schneider).

- Director:

- Joseph Losey

- Cast:

- Richard Burton, Alain Delon, Romy Schneider

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Babe (1995)

1h 31min1h 31min

1h 31min1h 31minIn Chris Noonan's seven-time Oscar-nominated adaptation of Dick King-Smith's bestseller, a piglet named Babe decides to become a 'sheep pig' and help collies Fly and Rex herd the sheep on the Australian farm owned by Arthur (James Cromwell) and Esme Hoggett (Magda Szubanski).

- Director:

- Chris Noonan

- Cast:

- James Cromwell, Christine Cavanaugh, Miriam Margolyes

- Genre:

- Children & Family

- Formats:

-

-

Animal Farm (1999)

Play trailer1h 30minPlay trailer1h 30min

Play trailer1h 30minPlay trailer1h 30minAlongside real animals and animatronics from Jim Henson's Creature Shop, Pete Postlethwaite plays Mr Jones in John Stephenson's live-action retelling of George Orwell's classic. He also voices Benjamin alongside Paul Scofield's Boxer, while the pigs are played by Peter Ustinov (Old Major), Kelsey Grammer (Snowball), Patrick Stewart (Napoleon), and Ian Holm (Squealer).

- Director:

- John Stephenson

- Cast:

- Kelsey Grammer, Alan Stanford, Ian Holm

- Genre:

- Drama, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

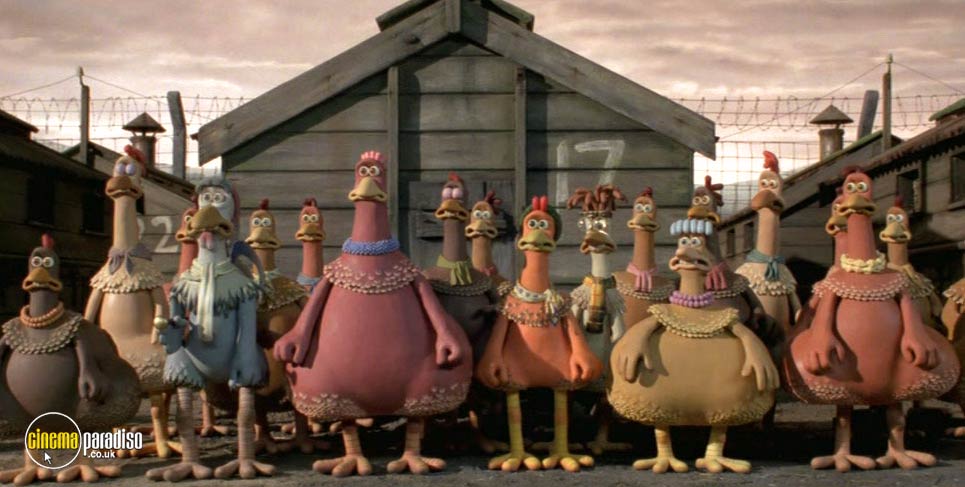

Chicken Run (2000)

Play trailer1h 21minPlay trailer1h 21min

Play trailer1h 21minPlay trailer1h 21minAardman hit its non-Wallace and Gromit peak in Peter Lord and Nick Park's inspired reworking of the POW movie format, as Ginger the chicken (Julia Sawalha) hopes that Rocky the rooster (Mel Gibson) can teach her friends to fly so that they can escape the sinister farm run by the cruel Mrs Tweedy (Miranda Richardson).

- Director:

- Peter Lord

- Cast:

- Mel Gibson, Julia Sawalha, Phil Daniels

- Genre:

- Children & Family, Anime & Animation

- Formats:

-

-

Home on the Range (2004) aka: Sweating Bullets

Play trailer1h 13minPlay trailer1h 13min

Play trailer1h 13minPlay trailer1h 13minIt's down on the farm Disney-style in this animated Western that sees dairy cows Maggie (Roseanne Barr), Mrs Calloway (Judi Dench), and Grace (Jennifer Tilly) round up a gang of animal pals to prevent rustler Alameda Slim (Randy Quaid) from ousting Pearl Gesner (Carole Cook) as the owner of the Patch of Heaven.

- Director:

- Will Finn

- Cast:

- Judi Dench, Cuba Gooding Jr., Jennifer Tilly

- Genre:

- Children & Family, Classics, Music & Musicals, Anime & Animation

- Formats:

-

-

Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009)

Play trailer1h 23minPlay trailer1h 23min

Play trailer1h 23minPlay trailer1h 23minDirector Wes Anderson teamed with Noah Baumbach to adapt Roald Dahl's story about the consequences faced by Mr Fox (George Clooney) his wife, Felicity (Meryl Streep, and their friends after farmers Walt Boggis (Robin Hurlstone), Nate Bunce (Hugo Guinness), and Frank Bean (Michael Gambon) unite to stop him from stealing their chickens.

- Director:

- Wes Anderson

- Cast:

- George Clooney, George Clooney, Meryl Streep

- Genre:

- Children & Family

- Formats:

-

-

The Death of Stalin (2017)

Play trailer1h 42minPlay trailer1h 42min

Play trailer1h 42minPlay trailer1h 42minInspired by a French graphic novel, Armando Iannucci's slickly scripted account of the struggle for power in the Kremlin in 1953 benefits from the exceptional playing of Steve Buscemi (Khrushchev), Michael Palin (Molotov), Simon Russell Beale (Beria), Jason Isaacs (Zhukov), and Jeffrey Tambor (Malenkov).

- Director:

- Armando Iannucci

- Cast:

- Steve Buscemi, Simon Russell Beale, Jeffrey Tambor

- Genre:

- Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

A Shaun the Sheep Movie: Farmageddon (2019)

Play trailer1h 23minPlay trailer1h 23min

Play trailer1h 23minPlay trailer1h 23minA sequel to the Shaun the Sheep Movie (2015) that was itself spun off from the Shaun the Sheep series (2007-16), this stop-motion romp sees Shaun and his friends at Mossy Bottom Farm encounter Lu-La, an alien from the planet To-Pa, just as the Farmer is about to launch his extraterrestrial theme park.

- Director:

- Will Becher

- Cast:

- Justin Fletcher, John Sparkes, Chris Morrell

- Genre:

- Children & Family, Anime & Animation

- Formats:

-

-

The Peasants (2023) aka: Chlopi

Play trailer1h 54minPlay trailer1h 54min

Play trailer1h 54minPlay trailer1h 54minAdapted from Wladyslaw Reymont's Nobel Prize-winning novel, DK and Hugh Welchman's oil-painted animation follows the fortunes of Jagda (Kamila Urzedowska ), a free-spirited Polish village girl, who is forced to wed Maciej (Miroslaw Baka), the richest man in Lipce, in spite of being besotted with his married son, Antek (Robert Gulaczyk).

- Director:

- Dorota Kobiela

- Cast:

- Kamila Urzedowska, Robert Gulaczyk, Miroslaw Baka

- Genre:

- Children & Family, Drama, Anime & Animation, Romance

- Formats:

-