One hundred years ago, F.W. Murnau was embarking upon a silent feature that would change cinema forever. Its reputation has dipped over the decades. But Cinema Paradiso reveals why every movie lover owes a debt to The Last Laugh (1924).

Whenever people talk about the greatest years in screen history, 1939, 1946, 1955, 1960, 1967, 1971, 1982, 1991, 1999, and 2007 often get mentioned in dispatches. Good cases could be made for several others. But nobody ever proposes 1924.

As Cinema Paradiso users can discover, this was the year of Carl Theodor Dreyer's Michael; Fritz Lang's two-part epic, 'Der Nibelungen' ( Siegfried and Kriemhild's Revenge ); and Paul Leni's Waxworks, as well as Raoul Walsh's Douglas Fairbanks swashbuckler, The Thief of Bagdad; John Ford's The Iron Horse, the Buster Keaton duo of The Navigator and Sherlock, Jr., and Erich von Stroheim's Greed. The latter adaptation of Frank Norris's McTeague originally ran for 42 reels before MGM production chief Irving G. Thalberg cut it down to 12. In the process, he might have destroyed the finest film ever seen, but we shall never know.

The world would be a better place if some more 1924 titles were available on disc, such as Yakov Protazanov's Aelita, D.W. Griffith's America, Hans Karl Breslauer's The City Without Jews, René Clair's Entr'acte and Paris qui dort, Robert Wiene's The Hands of Orlac, Victor Sjöström's He Who Gets Slapped, Mauritz Stiller's Gösta Berlings Saga, Marcel L'Herbier's L'inhumaine, and Fred C. Neymeyer and Sam Taylor's Harold Lloyd gems, Hot Water and Girl Shy. But we can still bring you two films from 1924 that had such an incalculable impact on the medium that their influence can still be felt today.

In Strike, the Latvian-born Sergei Eisenstein found a way to capture the dynamism of daily life by borrowing the editing techniques devised by Lev Kuleshov, who released his own masterpiece in 1924, The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks. As we saw in A Brief History of Soviet Cinema, Eisenstein pieced together short sequences of frames in order to create actions and metaphors that expanded the vocabulary and extended the grammatical breadth of the moving image.

Every bit as important as montage, however, was the so-called 'unchained camera' technique patented by director Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, screenwriter Carl Mayer, and cinematographer Karl Freund for Der letzte Mann (aka The Last Laugh). Employed in conjunction with 'invisible editing', this method of moving the camera around the set on a wheeled dolly in order to place the viewer in the centre of the action was seized on by film-makers across the planet, including those in Hollywood, where it became the bedrock of the classical narrative style that would survive beyond the transition to sound in 1927 and into the modern blockbuster era.

Die Filmwoche called The Last Laugh, 'the true birth of film as a form of art'. So, what was it about and why is it considered so groundbreaking?

A Deceptively Simple Story

The action opens with a caption that reads: 'Today you are the first, respected by everyone, a minister, a general, maybe even a prince - Do you know what you'll be tomorrow?'

As the letters disappear, the on-screen darkness gives way to the view from a lift hurtling downwards towards the lobby of the Atlantic Hotel. The camera glides across the polished floor towards the revolving door of the main entrance. Through the glass, we see a doorman (Emil Jannings) in his waterproofs. escorting guests to their taxis beneath a large umbrella. Although aged, with a white handlebar moustache and mutton-chop whiskers, he is very much the man in control. Cars pull up at the click of his fingers and a page bobs forward to take the umbrella so that the commissionaire can take his position under the grand sign.

One cab, however, has a large trunk on its roof and the page is too busy to lend the doorman a hand in carrying it into the lobby. Feeling the strain, the veteran takes a seat to compose himself over a glass of water. However, he is spotted sitting down on the job by the manager (Hans Unterkircher), who jots down the incident in his notebook.

No sooner has he gone, however, than the doorman is back on his feet and removing his oilskins to reveal a magnificent braided jacket and peaked cap. Checking his facial hair in a pocket mirror, he resumes the duties in which he takes such pride. He salutes to the guests and chuckles when a couple of women take his arm, as he shelters them from the rain and settles them in their taxi.

At the end of his shift, the doorman returns to the tenement where he lives. It's hardly the most salubrious residence, but his neighbours greet him fondly, as though basking in his reflected glory. He lives with his niece (Maly Delschaft), who is about to marry the man (Max Hiller) who lives upstairs with his aunt (Emilie Kurz). He gets sentimental about her leaving the nest and looks ruefully at her wedding dress and samples one of the cakes she has baked. But he knows she is happy and that's all that matters, as they embrace.

The next morning, the woman across the landing (Emmy Wyda) stops beating her carpet as the doorman passes, in case she gets dust on his uniform. In the courtyard, he pauses to cheer up a little girl who was being bullied and gives her a sweet before heading off to work. Much to his horror, however, another doorman is stationed on the pavement and the page informs him that he is wanted in the manager's office.

The camera peers through the glass door before focussing on the typed letter in the old man's hand. He fumbles for his glasses before reading that the manager believes the episode with the trunk proves he is no longer fit for heavy lifting. The missive concludes: 'In consideration of your long service with us, we have found another position for you by arranging for our oldest employee to be admitted to a home, so from today you will take over his duties.'

The letters blur before the doorman's eyes, as he tries to take in their meaning. When his appeal to the manager is brushed aside, he attempts to lift a trunk in the corner of the room to demonstrate his strength. But he falls under the weight and the furious manager orders an underling to remove the uniform and lock it in a cupboard. Devastated by the humiliation of being divested, the doorman slips the closet key into his pocket when the manager is called away before meekly following the housekeeper, who gives him a white jacket and a bundle of towels to take with him into the gentleman's washroom.

Back at the tenement, the niece gets married and returns home for a celebration. Knowing he can't attend the event without his uniform, the doorman waits until the manager has gone home before creeping into the office to retrieve his tunic. Avoiding the nightwatchman (Georg John), he tiptoes through the lobby and runs across the road. Fighting for breath, he leans against a wall before donning the greatcoat. Arriving home, he pauses to correct his stooped posture before striding across the courtyard to be welcomed as an honoured guest at the feast.

Once in the company of neighbours who still believe him to be an important man, the doorman gets tipsy. Dreamily, he imagines himself to be outside the Atlantic in all his pomp. He sees a number of porters struggling with a trunk and lifts it above his head like a matchbox. However, the view of the street outside begins to distort, as the combination of drink and despair kicks in.

Waking next morning, the doorman is fussed over by the groom's aunt, who makes him coffee and sews a missing button on his tunic. She waves him off from the window, as the ex-doorman wanders to work with a hangover. However, he is shaken back to sobriety by the sight of his rival outside the entrance and he leaves the uniform in the left luggage office at the nearby railway station before slinking down the stairs to his new place of work.

Slipping on his white coat, the old man busies himself around the washroom. But he can barely bring himself to look at the patron washing his hands (Olaf Storm) as he proffers him a towel. However, he makes it to lunchtime and is sipping a bowl of thin gruel when the aunt pays him a surprise visit with a tasty dish. She's appalled to see that he is not the doorman commanding the pavement and rushes away before he can explain.

Crushed by the shame of being rumbled, the old man becomes distracted and so infuriates a pot-bellied customer (Hermann Vallentin) with his slapdash service that he reports him to the manager. Meanwhile, the aunt scurries back to the tenement to tell all and sundry that the fellow had been lying to his neighbours all along and that his airs and graces had been entirely unwarranted.

Although aware that this is what must be happening, the old man nevertheless collects the uniform from the station and makes his way upstairs wearing his livery. He is dismayed to find his apartment empty and crushed when his niece refuses to come to the door of her new rooms. Inviting him inside, away from prying eyes, the husband stands aside while the old man sheepishly looks up at his niece. She is too ashamed to console him and her uncle staggers into the night to return the stolen uniform to the watchman. Slumping down on to the washroom chair in abject dejection, he is the picture of misery. Taking pity, the watchman covers him with his coat, as the old man falls asleep.

This should be the end of the sorry saga. But the film's sole intertitle appears to inform the audience: 'Here our story should really end, for in actual life, the forlorn old man would have little to look forward to but death. The author took pity on him, however, and provided quite an improbable epilogue.'

As the action resumes, various hotel guests are roaring with laughter at an article in the morning newspaper. Apparently, a Mexican millionaire named A.G. Monney had inserted a clause in his will that his fortune should go to the last man who had served him. This just happened to be a certain washroom attendant, who is now stuffing his face in the Atlantic dining-room and being waited on by staff who aren't as amused by the situation as the wealthy patrons. The manager is certainly discomfited by the turn of events and can barely bring himself to look as the nightwatchman teeters in with an armful of parcels after a shopping expedition.

He joins the elevated doorman at his table and starts tucking into meat dishes, as his friend fiddles with his monocle, swills down champagne, and lights up a cigar. Excusing himself, he ventures down into the washroom, where he gives the new attendant a generous tip. Indeed, he slips a gratuity to each of the footmen, as he makes his way to the horse carriage waiting outside the entrance. He helps the nightwatchman aboard and pushes away the doorman when he tries to stop a beggar asking for cash. Happy to share his good fortune, the revitalised old man pulls him into the carriage and the coda concludes with a backwards salute.

Setting the Scene

As Cinema Paradiso members will know from 100 Years of German Expressionism, F.W. Murnau was on something of a roll after the release of The Haunted Castle (1921), Nosferatu, Phantom (both 1922), and The Finances of the Grand Duke (1924). Unlike such contemporaries as Robert Wiene, Karl Heinz Martin, and Fritz Lang, the 35 year-old had largely resisted using Expressionist tropes in his first 13 films. Having served his apprenticeship under theatre maestro Max Reinhardt, Murnau favoured the brand of intimate chamber drama realism known as 'Kammerspiel'.

On joining German's biggest studio, UFA, Murnau announced that he wanted to perfect a universal cinematic language that could remove the need for the intertitles that slowed the action in silent films and liberate the camera's expressive potential. 'All our efforts,' he wrote, 'must be directed towards abstracting everything that isn't the true domain of the cinema. Everything that is trivial and acquired from other sources, all the tricks, devices and clichés inherited from the stage and from books.'

He got his chance to undertake his experiment when screenwriter Carl Mayer fell out with director Lupu Pick. Having made his reputation with Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920), Mayer had turned his fascination with subjectivity on to everyday scenarios that reflected the realities of life in the Weimar Republic. Leopold Jessner's Backstairs (1921) and Pick's Shattered (1922) and Sylvester (1924) were essentially psychological dramas whose lower-class settings gave them a socio-political flavour. But what made them really stand out was the purity of their aesthetic approach, as they resisted intertitles in order to create what was called 'Stimmung', or a pervading atmosphere that could only be presented visually.

It's a shame that none of these Kammerspielfilme have been released on disc in the UK, as they sought to free the moving image from the printed intertitles carrying dialogue or scenic descriptions that shaped the audience's response to the imagery.

Eager to collaborate with someone he believed worked in 'the true domain of the cinema', Murnau leapt at the chance to replace Pick when he quit The Last Laugh and they set about ensuring that the only writing shown on screen was diegetic rather than interpolated. Consequently, they conveyed key information in the letter read by the doorman in the manager's office and the newspaper article perused by the amused guests in the Atlantic dining-room. Apart from some frosted lettering on top of the weddings cakes, the street signs, shop fronts, and posters visible within the mise-en-scène were given in a cod version of Esperanto.

These were incorporated into the sets by designers Walter Röhrig (one of the founders of Caligarism) and Robert Herlth, who had made his mark with Fritz Lang's Destiny (1921). While Murnau had used real locations to chilling effect in Nosferatu, he wanted to control every aspect of the visuals in The Last Laugh. Thus, he had Röhrig and Herlth erect exteriors with a stylised sense of realism on the UFA backlots at Berlin-Templehof and Potsdam-Babelsberg. The hotel and tenement interiors were equally meticulous in combining authenticity with artifice and, thus, anticipated the brand of studio realism associated a decade later with French Poetic Realism (see Cinema Paradiso's Brief History ).

For the street outside the Atlantic, a sloping thoroughfare was created that dropped 10ft in receding into a distance in which toy cars replaced the outsize bus and Mercedes that were positioned in the frame immediately outside the hotel. The height of the buildings was also tapered to reinforce the illusion. Much thought was also given to the revolving door in the hotel entrance, as this not only separates an enclave of privilege and luxury from the wider world, but it also acts as a kind of wheel of fortune reflecting the doorman's shifting fate.

Inside the hotel, there is lots of glass that the doorman can see through while being kept at a deferential distance. Reflective surfaces also play their part, whether it's the mirror the vain old man keeps in his uniform pocket to ensure his whiskers look suitably impressive or the looking glasses on the washroom wall, in which he can see himself for who he really is after being so abruptly demoted. It's almost tempting to look into the future and see the Wicked Queen's magic mirror in Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937).

Future Hollywood director Edgar G. Ulmer worked as an assistant on The Last Laugh (tap his name into the Cinema Paradiso searchline to find such gems as People on Sunday, 1929 and Detour, 1945). But, while he went on to great things, little is known about G. Benedict, who is credited with having designed the doorman uniform that is so pivotal to the action.

Although some see this as an anti-military parable, Murnau and Mayer were equally interested in the old maxim, 'clothes maketh the man'. Iconic screen historian Lotte Eiser went so far as to say that the film 'can only be understood in a country where uniform is King, not to say God. A non-German mind will have difficulty in comprehending all its tragic implications.'

The doorman was probably too young to have fought in Otto von Bismark's wars of unification and too old to have seen action on the Western Front. But he understands the significance of a uniform, even in a country in which the Prussian militaristic mindset has been replaced by a disarmed, democratic egalitarianism. Indeed, his entire self-worth is bound up in his uniform. It makes him stand out as an authority figure on the pavement outside the hotel, while its grandeur sets it apart from the liveries worn by the footmen and pageboys and even the smart suits worn by the management and the male guests. Moreover, the braided trenchcoat earns the fellow the respect of his neighbours, who take pride in the fact that one of their own can cut such a dashing figure and command respect in the big city.

Some critics insist that Emil Jannings was made up by Waldemar Jabs to resemble the recently deposed Hohenzollern ruler, Kaiser Wilhelm II. However, his side-whiskers make him look more like the penultimate Hapsburg emperor, Franz Josef, who would later be played by Karl Böhm opposite Romy Schneider in Ernest Marischka's 'Sissi trilogy' (1955, 1956 and 1957) and Florian Teichtmeister in Marie Kreutzer's Corsage (2022). Either way, the character is intended to reflect a shift in Germanic history and it's entirely possible that Murnau added the so-called 'happy ending' to mark the start of a period of stability after the chaos of the postwar period of reparations and revolutions that had witnessed rampant inflation threatening Weimar's newly inaugurated democratic institutions. The year before Murnau started shooting, French and Belgian troops had occupied the Ruhr in reprisal for defaulted payments on the compensation imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Moreover, Adolf Hitler and his National Socialists had attempted a putsch in Munich. While Murnau was shooting The Last Laugh, however, the economy received a significant boost by the implementation of the Dawes Plan and it's no coincidence that the humbled doorman should also be the beneficiary of unexpected largesse from the New World.

When he rides off in the open landau at the end of the film, it's unlikely that the happenstantial heir is heading back to his erstwhile residence. This was designed by Röhrig and Herlth to contrast with the splendour of the Atlantic and show how everyone literally lives on top of each other in cramped conditions. There's the odd canted angle to exploit when the old man's at a low ebb and when the tittle-tattles start shrieking their misinformed gossip from window to window. The occupants are far from destitute, but times are clearly hard and there's an understandable sense of indignation in their response to the fake news that their preening neighbour has had ideas above his station all along and had duping them into thinking he was a somebody when he was merely a toilet attendant.

Even the fallen idol's niece believes the worst of her uncle and it's interesting to contrast the uniform with her wedding dress and the white jacket that the old man will be forced to wear in his demeaning new role. The gown will transform the niece into a wife and there's an irony in the fact that she moves upstairs (and, therefore, up in society) just as her uncle is going in the opposite direction.

UFA Unchained

The film camera first started to move when Lumière agent Alexandre Promio placed a Cinématographe in a gondola in December 1897 to shoot Panorama du Grand Canal vu d'un bateau. An early example of the camera being moved for dramatic emphasis came in Oscar C. Apfel's The Passer By (1912), while Allan Dwan used an automobile to follow actor William H. Crane for a shot in David Harum (1915). Dwan invented the crane used by D.W. Griffith in Intolerance (1916), who was seeking to outdo the moving camera shots employed by Giovanni Pastrone in Cabiria (1914), which was partly photographed by Eugenio Bava, whose son and grandson became the famous horror directors, Mario and Lamberto Bava (type in their names and get clicking).

Such was the influence of this Italian superspectacle that images taken with a moving camera were initially known as 'Cabiria shots'. We now call them 'dolly shots' and they become common in films in Europe and America after Murnau and Freund had refined the 'entfesselte Kamera' or 'unchained camera' technique in The Last Laugh.

The opening sequence hints at the kineticism to come, as the camera descends in an elevator before tracking across the hotel lobby to the main entrance. Despite the presence of a subtle cut, the impression is one of a single continuous shot and Freund achieved this by holding the camera while being seated in a chair mounted on a platform that was pushed across the set by grips. Freund would insist that the camera was fixed to a bicycle, while Ulmer claims a baby's pram was used. But Freund's chair rig can be seen in the reflection from the glass door.

The view through the lift grille was consciously designed to resemble film flickering through the gate of a projector, while the revolving door evoked the machine's spinning reels as it casts the images on to the screen. By drawing attention to his technique, Murnau sought to remind the audience that they were watching manufactured reality and this self-reflexivity would become a key component of the nouvelle vague 35 years later.

Mayer had written the camera movements into the screenplay, but Freund devised ingenious ways of implementing them. He even disguised tilts and pans taken from a static tripod to simulate movement. But the unchained camera wasn't just a gimmick, as motion around the set brought a new sense of depth to on-screen space and this was given additional dimensionality by the lens's increased field of vision. Theorist André Bazin would become the champion of this 'mise-en-scène' technique that would be refined by cinematographer Gregg Toland in William Wyler's The Letter (1940) and Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941) before being taken up by Christian Matras in the Max Ophüls quartet of La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1951), Madame De... (1952), and Lola Montès (1955).

Another notable dolly shot brings the camera closer to the windows of the manager's office, as the doorman is presented with his letter of demotion. A deft dissolve takes us through the glass and into the room. But the camera later lingers outside the doors of the washroom, as the manager descends to admonish the old man after his contretemps with the angry customer. This is clearly because Freund couldn't find a way of getting the camera down the steps. But Murnau uses the moment to emphasise his decision to remain aloof, even eschewing a simple edit that would have enabled us to witness the confrontation.

If he spares the ex-doorman's blushes here, Murnau takes us into his subconscious during the celebrated drunk scene. The sequence begins with an audacious bid to convey sound through imagery, as a close-up of the horn of the trumpet being played in the courtyard is followed by a floating swoop that suggests the music rising into the doorman's ear at the wedding party. In fact, Freund achieved the effect by placing the camera in a basket and lowering it down from the tenement set on a wire before reversing the footage during editing to suggest upward movement.

As the effects of a night's carousing hit the porter, the room seems to spin around him. Freund achieved this effect by seating Jannings on a chair positioned on a revolving platform. As he drifts off to sleep, Freund allowed the lens to slip out of focus before moving the camera to convey a sense of swaying that was made all the more disorientating by the blurring of the props and the streaking of the set with shafts of light. Murnau wasn't the first to attempt to explore a character's psychological state, but there's a boldness to the perspectival techniques that implies either he or Freund was aware of the avant-garde work of Oskar Fischinger, Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling, and Walter Ruttmann or the cinéma pur of such Paris-based Dadaists as René Clair, Man Ray, and Marcel Duchamp.

The hotel's revolving door proves key to the more Expressionist aspects of the dream sequence, as it's elongated and superimposed on to the old man's skull to suggest it that it has plunged into his brain and scrambled his thoughts. Amidst the canted angles, visual distortions, and jagged striations of light, Freund even tosses in a little handheld footage to authenticate the subjective gaze.

Subjective shots motivated by the doorman's emotions make use of what's called 'affective camera movement', while those that more objectively follow his physical behaviour employ 'action movement'. But Murnau also makes adroit use of overlaid images and montage to generate a sense of sound bouncing off the tenement walls during the gossip sequence. The same walls are also transformed into screens on to which the doorman's shadow is cast on his contrasting returns home. Note how his stooped figure creates a monstrously crepuscular shape that would not have been out of place in Nosferatu. Yet, Murnau is also revealing that the old man is a shadow of his former self.

We now take for granted the camera's ability to convey time, space, and sound. But, in 1924, this was revolutionary and it's worth noting that no one in the intervening century has found a better way to use the camera as a storytelling tool. Marcel Carné, who would embrace Murnau's technique in such Poetic Realist masterpieces as Le Quai des brumes, Hôtel du Nord (both 1938), and Le Jour se lève (1939), acknowledged his debt in noting that 'The camera glides, rises, zooms or weaves where the story takes it. It is no longer fixed, but takes part in the action and becomes a character in the drama.'

Freund would later attempt to downplay Murnau's contribution to the visuals by averring that he paid no attention to the lighting and rarely looked through the viewfinder. But he deliberately placed figures and objects within the frame in order to create visual and psychological relationships so that they became 'units in the symphony of the film'. He also cut on movement in employing the 'invisible editing' technique that had been devised by D.W. Griffith to disguise his edits. While Eisenstein abandoned this strategy in Strike, Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1928) because it smacked of the class disparity that underpinned capitalist society, Murnau combined it with the unchained camera to edge cinema towards the long takes that would reach their zenith in the magisterial Steadicam swoops in Aleksandr Sokurov's Russian Ark (2002).

Dropping into the set while working as an assistant on Graham Cutts's The Blackguard (1925), Alfred Hitchcock was so impressed by Murnau's technique that he employed it on The Farmer's Wife (1928), which is one of several Hitchcock silents available to rent from Cinema Paradiso. But what's often forgotten about this method of filming is the part played by the actors. As we shall see in the next section, Jannings's performance has increasingly come to be seen as stylised and hammy. However, his facial expressions in close-up and his shifts in body language are crucial to Murnau's bid to coax the viewer into seeing events from the doorman's perspective. The camera and editing techniques may infer the character's inner emotions, but it's Jannings who ensures that the audience identifies with the doorman's ordeal to the extent that they are drawn into the story, whether they're watching in 1924 or 2024.

Das letzte Lachen

After spending much of the year on the project, Murnau premiered his masterpiece in Berlin on 23 December 1924. Three versions were prepared for the German, American, and international markets. The domestic release was entitled Der letzte Mann, which was translated directly in various languages around the globe. In English-speaking territories, however, the film was more optimistically called The Last Laugh, which seems to reference the 'happy ending' that has forever been highly contentious.

On-screen captions were almost as old as moving pictures. The first film to use 'intertitles' was a 1903 adaptation of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, an extract of which can be found in Charles Musser's Before the Nickelodeon: The Cinema of Edwin S. Porter (1982). So integral had these cards carrying dialogue or plot descriptions become that Joseph W. Farnum won the first and only Academy Award for Best Writing - Title Cards, which was presented in 1929, by which time talkies had rendered the craft virtually obsolete. Curiously, the Oscar was not associated with a named film, although the titles for which Farnum was being rewarded are presumed to be Herbert Brenon's Laugh, Clown, Laugh and the Sam Wood duo of The Fair Co-Ed and Telling the World.

Murnau and Mayer were no fans of intertitles, as they felt they were 'an obstructive presence' and dissuaded directors from finding visuals means of conveying information and emotion. Thus, they restricted their use in The Last Laugh to a prefatory remark and an authorial interjection justifying the addition of an epilogue that plucked the ex-doorman out of the trough of despair and placed him on easy street.

Debate has long raged about the intention and meaning of the coda. In his monograph on the film, Samuel Frederick insists that the sequences after the intertitle are an alternative ending, which, rather than providing a cornball conclusion, serves to emphasise the reality of what actually happens to the doorman in a harsh world that would have been all too familiar to a German audience in 1924.

On the evidence presented in the melodrama, the doorman is a decent chap. He works hard and is popular with both staff and clientele at the Atlantic. The old man is also devoted to his niece (although some suggest she's actually his daughter) and wants only the best for her on her wedding day - hence not coming home without his uniform and risking showing her up in front of the neighbours. There's no question that he's pompous and misguided in believing he's superior to his fellow residents simply because he's a lackey to the rich. One could even argue that there's a touch of male chauvinism on top of his class snobbery.

But he doesn't lose his position at the hotel because of his character. The manager simply deems him too old to perform a highly visible role that sets the tone for the business. His fault is sitting down on the job, not cheating anyone or doing down a colleague. He has been loyal to the hotel and, some might argue, the manager has been fair to him by finding him another post. Indeed, an executive at UFA found the ending unbelievable because a washroom attendant earned more than a commissionaire

The key to understanding the conclusion lies in the old man's costume changes. Although bereft of military regalia, the uniform evokes the Hohenzollern era that had only ended six years earlier. Weimar was still in its infancy and many viewed its teething troubles with a sense of regret for the loss of imperial status and shame for defeat in both the Great War and the ensuing peace. Deciding whether to join the neighbours deriding the old man or the hotel patrons amused by his sudden elevation put the audience in a tricky spot in 1924, as their response would betray their own socio-political viewpoints. But hindsight makes the choice even more difficult.

Laughing at the lavatory attendant places us on the side of those who have delighted in his downfall. But laughing with him or sympathising with him for losing his uniform risks aligning us with those who pined for Wilhelmine militarism and accepted Nazism as a tolerable substitute. Samuel Frederick reminds us that the doorman is not necessarily a symbol of the old order. He might wear a uniform that evokes the Prussian past, but Murnau is warning us that appearances can be deceptive and that we shouldn't judge the doorman because of the trappings by which he sets such store.

He also suggests that the doorman isn't rooted in the past, but symbolises an old country trying to make a fresh start and being given the chance to pick itself up off the ground by a windfall from the Americas. Frederick also notes that some have seen the ending as bit of wish fulfilment on the gay director's behalf, as the doorman derives enormous pleasure from being able to share his good fortune with the watchman, the only person to show him compassion at his lowest ebb and now his companion as they ride off together into the sunset.

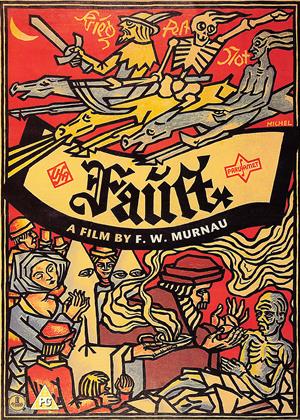

Much changed in the years following The Last Laugh's release, however. Jannings would reunite with Murnau on Tartuffe (1925) and Faust (1926) before heading to Hollywood following the signing of the Parufamet Agreement to increase US-German cinematic collaboration. At the first Oscar ceremony, Jannings would win Best Actor for Josef von Sternberg's The Last Command (1928) and Victor Fleming's The Way of All Flesh (1927), of which only fragments now remain.

Bouncing back from being upstaged by Marlene Dietrich while playing another respectable man stripped of his rank in Von Sternberg's The Blue Angel (1930), the Swiss-born Jannings became an enthusiastic supporter of the Nazis. As is shown in Rüdiger Suchsland's eye-opening documentary, Hitler's Hollywood (2017), he was made an Artist of the State by Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels after headlining numerous prestige pictures. When the war ended, he used his Oscar to claim an association with the United States during his denazification process and was allowed to live in retirement as an Austrian citizen until his death in 1950. By contrast, Georg John, who had gone on to play the balloon seller in Fritz Lang's M (1931), was Jewish and barred from acting in the Third Reich. Unable to leave, he perished in the £ódŸ ghetto in 1941.

The shadow of Jannings's Nazism still falls across The Last Laugh. His performance has been dismissed by many as old-fashioned and hamfisted. Silent acting takes getting used to after 97 years of talking pictures. But Jannings does exactly what Murnau requires him to do in showing how the mighty can fall. In his feted book, From Caligari to Hitler (1947), Siegfried Kracauer claimed that Murnau and Mayer's intent was tragic. However, he suggested that the conclusion was a cheeky send-up of Hollywood's tendency to slap a happy ending on to movies regardless of their content. The dishevelled washroom attendant may well be the last man from a bygone era, but he also gets to have the last laugh.

In the years that followed, German culture moved away from Expressionism towards Neue Sachlichkeit or the New Objectivity that manifested itself in the genre of 'Strassenfilme' or 'street films' that had begun with Karl Grune's The Street (1923). The best known example is G.W. Pabst's The Joyless Street (1925), which co-starred Asta Nielsen and Greta Garbo. With the emphasis falling more on authenticity than atmosphere, features like The Love of Jeanne Ney (1927), Pandora's Box, and Diary of a Lost Girl (both 1929) also impacted on Hollywood, as it started to wire for sound. Cinema Paradiso users can also order Pabst's first talkies, Westfront 1918 (1930), Kameradschaft, and The Threepenny Opera (both 1931), which also proved highly influential.

Unlike Lang, Ulmer, Billy Wilder, William Wyler, Fred Zinnemann, Robert Siodmak, and a host of others who left for Hollywood, the Austrian Pabst continued to work in Germany during the war. Murnau signed to Fox, for whom he made the peerless silent classic, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), as well as City Girl (1930) and Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (1931). A week before the latter previewed, however, he died at the age of 42 from injuries sustained in a car crash in Santa Barbara.

Hitchcock considered Der letzte Mann to be an 'almost perfect film', while critic Paul Rotha declared that it 'definitely established the film as an independent medium of expression...Everything that had to be said...was said entirely through the camera...The Last Laugh was cine-fiction in its purest form; exemplary of the rhythmic composition proper to the film.' In an age in which dialogue is frequently used for exposition and images are constructed from pixels, Murnau's experiment in visual purity remains accessible and remarkable. It says much, however, that when it underperformed at the German box office, UFA released a version with intertitles that did better business. Moreover, when Harald Braun remade Der letzte Mann in 1955, with Hans Albers and Romy Schneider, it discarded much of Mayer's scenario in delivering a standard issue drama. It's still a shame, however, that no one has ever thought to include it as an extra on a DVD release.

-

Greed (1924) aka: Greedy Wives

2h 20min2h 20min

2h 20min2h 20minDentist John McTeague (Gibson Gowland) marries Trina Sieppe (ZaSu Pitts) after she wins $50,000 on the lottery. However, she refuses to spend a dime and jealous rival, Marcus Schouler (Jean Hersholt), is eager to drive the couple apart.

- Director:

- Erich von Stroheim

- Cast:

- Zasu Pitts, Gibson Gowland, Jean Hersholt

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Classics, Action & Adventure, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Strike (1925) aka: Stachka

1h 27min1h 27min

1h 27min1h 27minWhen a worker commits suicide, his colleagues call a strike against the poor conditions and the callousness of the management. Refusing to yield to their demands, the bosses call in the police.

- Director:

- Sergei Eisenstein

- Cast:

- Maxim Shtraukh, Anatoli Kuznetsov, Grigori Alexandrov

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) aka: Izlazak sunca

Play trailer1h 31minPlay trailer1h 31min

Play trailer1h 31minPlay trailer1h 31minDespite being contentedly married to a devoted wife (Janet Gaynor), a country man (George O'Brien) has his head turned by a woman from the city (Margaret Lindsay) and he leaves home.

- Director:

- F.W. Murnau

- Cast:

- George O'Brien, Janet Gaynor, Margaret Livingston

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Last Command (1928) aka: Последња команда

1h 28min1h 28min

1h 28min1h 28minHaving lost everything in the Russian Revolution, Grand Duke Sergius Alexander (Emil Jannings) finds himself in Hollywood, where he is cast as a general in a movie directed by Leo Andreyev (William Powell), his rival for the love of Natalie Dabrova (Evelyn Brent).

- Director:

- Josef Von Sternberg

- Cast:

- Emil Jannings, Evelyn Brent, William Powell

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (1936) aka: The Crime of Monsieur Lange

1h 16min1h 16min

1h 16min1h 16minA writer of popular cowboy stories, Amédée Lange (René Lefèvre) falls for tenement neighbour, Valentine Cardès (Florelle), an old flame of publisher Paul Batala (Jules Berry), who has faked his death in order to avoid creditors.

- Director:

- Jean Renoir

- Cast:

- Florelle, René Lefèvre, Jules Berry

- Genre:

- Drama, Comedy, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

A Touch of the Sun (1956) aka: Auringon kosketus

1h 18min1h 18min

1h 18min1h 18minBill Darling (Frankie Howerd) is the hall porter at the Royal Connought Hotel. He decamps to the South of France on being left a fortune by a grateful guest. However, when he learns that his former workplace has let its standards slip, he returns to take over.

- Director:

- Gordon Parry

- Cast:

- Frankie Howerd, Ruby Murray, Dennis Price

- Genre:

- Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

The Night Porter (1974) aka: Il portiere di notte

Play trailer1h 53minPlay trailer1h 53min

Play trailer1h 53minPlay trailer1h 53minIn 1957, having survived the Holocaust, Lucia (Charlotte Rampling) realises that a Viennese hotel porter is SS officer Maximilian Theo Aldorfer (Dirk Bogarde). They embark upon a sadomasochistic relationship that revolves around his uniform.

- Director:

- Liliana Cavani

- Cast:

- Dirk Bogarde, Charlotte Rampling, Philippe Leroy-Beaulieu

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Babette's Feast (1987) aka: Babettes gæstebud

Play trailer1h 44minPlay trailer1h 44min

Play trailer1h 44minPlay trailer1h 44minWhen she wins 10,000 francs on the lottery, 19th-century Parisian fugitive Babette Hersant (Stéphane Audran) decides to thank the Danish spinster sisters who had given her sanctuary in their Jutland home with an exquisite banquet.

- Director:

- Gabriel Axel

- Cast:

- Stéphane Audran, Bodil Kjer, Birgitte Federspiel

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

Downfall (2004) aka: Der Untergang

Play trailer2h 29minPlay trailer2h 29min

Play trailer2h 29minPlay trailer2h 29minAs the Battle of Berlin rages in the spring of 1945, Adolf Hitler (Bruno Ganz) takes refuge in an underground bunker. Retaining the support of his inner circle, he continues to issue increasingly desperate orders, as he refuses to contemplate the humiliation of defeat.

- Director:

- Oliver Hirschbiegel

- Cast:

- Bruno Ganz, Alexandra Maria Lara, Ulrich Matthes

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Play trailer1h 35minPlay trailer1h 35min

Play trailer1h 35minPlay trailer1h 35minWith fascist forces threatening to take control of the Eastern European state of Zubrowka, hotel concierge Monsieur Gustave H. (Ralph Fiennes) is bequeathed a priceless Renaissance painting by Madame Céline Villeneuve Desgoffe-und-Taxis (Tilda Swinton). However, her family accuse him of murdering her.

- Director:

- Wes Anderson

- Cast:

- Ralph Fiennes, F. Murray Abraham, Mathieu Amalric

- Genre:

- Comedy

- Formats:

-