Following the death of Claudia Cardinale at the age of 87, Cinema Paradiso looks back on the remarkable life of a unique star.

In her 2005 autobiography, My Stars, Claudia Cardinale wrote: 'I was a movie star from a very young age. But I don't deserve any credit for that - it was a question of fate. There was always a lucky star watching over me.'

During a seven-decade career, Cardinale saw her fair share of stars, as she was teamed three times each with Alain Delon and Jean-Paul Bemondo, four times with Marcello Mastroianni and Burt Lancaster, and five times with the Italian heartthrob, Vittorio Gassman. She also worked with some of the most celebrated auteurs in recent cinema history, although she was equally committed when performing in what Italian critics call 'divertissements'.

'For me, cinema is a dream,' Cardinale claimed. 'The most beautiful thing. I don't like to see banality in films. I want to see something that makes you think and dream.' But she also saw making pictures as an adventure whose next twist or turn could never be anticipated. 'When I was young,' she said, 'I wanted to go everywhere and be everyone, and with this work, I have. The interesting thing for an actress is not to do what she wants to do, but to be somebody else. I was blonde, I was brunette, I was a princess, I was a whore. I was everything. You are not yourself in front of the camera. You can live many lives, instead of one. I think I've been lucky.'

The Girl From La Goulette

Claude Joséphine Rose Cardinale was born on 15 April 1938 in the municipality of La Goulette, a few miles from the capital of Tunisia. Mother Yolande Greco's parents had sailed from Trapani in Sicily and set up a small ship-building company in Tripolitania in Libya. But it was in Tunis that she met Francesco Cardinale, a railway engineer from the Sicilian town of Gela, who used the island dialect that Claude and her younger sister and two brothers grew up speaking, along with French and Arabic. 'I still feel a little bit Tunisian,' Cardinale told the press in 2023, when she returned to her birthplace to have a street named after her.

Claude was a tomboy who knew how to look after herself. 'As a teenager,' Cardinale recalled, 'I was wild, a bit crazy, a tomboy, I got into fistfights with boys just to show them girls can be stronger than them. I have always accepted challenges. When I was young, I remember catching the train after it had pulled out, I used to run and jump on even though I was on the platform, perfectly in time for the departure, just to show I could do it. This attitude also helped me on set when I found myself the only woman surrounded by men, I wasn't intimidated, I felt able to compete with them. My philosophy of life has always been: If you want, you can. You can't be weak if you want to do this job.'

Francesco wanted Claude to become a teacher and she was educated along with Blanche at the private school run by the nuns of the convent of Saint Joseph de l'Apparition in Carthage. She transferred to the Paul Cambon Technical College, where she was described as 'silent, weird and wild' after she had become obsessed with Brigitte Bardot, who had become a global phenomenon following her fearless performance in Roger Vadim's And God Created Woman (1956).

In that same year, Cardinale made her own screen debut in Anneaux d'or, a neo-realist drama directed by René Vautier that centred on a group of fishermen who sell their gold rings in order to buy a boat after the village's biggest employer closes down. The short would eventually be shown at the Berlin Film Festival, but it brought Cardinale to the attention of another French director, Jacques Baratier, who cast her as Amina opposite a young Omar Sharif in Goha (1958), which won a jury prize at the Cannes Film Festival for its story about a bored bride (Zina Bouzaiade), who falls for a poor donkey drover.

Cardinale was anything but starry-eyed after the experience. But, she went along with the flow, when she was plucked from the crowd during Italian Cinema Week in Tunis in 1957 and crowned 'The Most Beautiful Italian Girl in Tunisia'. Her prize was a trip to the Venice Film Festival, where she had the paparazzi fawning over her when she appeared on the Lido in an emerald green bikini.

A host of producers tried to persuade Cardinale to sign an exclusive contract. But she opted, instead, to study acting under Tina Lattanzi at the famous Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Rome. Unfortunately, Cardinale didn't speak Italian and struggled so badly in class that she decided to quit after the first term. Once back in Tunis, however, the 17 year-old fell into an abusive relationship with a Frenchman, who was 10 years her senior and who insisted that she had an abortion when she realised she was pregnant. Determined to keep her child, Cardinale agreed to sign a seven-year deal with producer Franco Cristaldi, whose Vides company was one of the power-players in 1950s Italian cinema.

Italy's Sweetheart

With her new name, Claudia Cardinale was cast as Carmelita, the Sicilian girl dominated by her cloddish brother in Mario Monicelli's Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958), a hilarious crime caper that starred Vittorio Gassman, Totò, Marcello Mastroianni, and Renato Salvatori as a gang of incompetent crooks. Even though she made some excellent films in this first phase of her career, this is the only title available on disc for Cinema Paradiso users - which is a massive shame, but just the way the UK home entertainment business works: there's always more chance of an old Hollywood film being released than anything continental.

As Cardinale later explained, 'It was, in a way, my film debut. Mario was an extraordinary person, with rare intelligence and memory. At the time I couldn't understand everything he was saying, with all the gesticulating and shouting I thought they were having arguments all the time.' In fact, Monicelli decided to have Cardinale's dialogue dubbed, even though she was playing a Sicilian character. But he had no idea that she had been pregnant during the shoot and Cristaldi decided to protect his investment from snooping journalists by sending her to London (on the pretext of learning English) to give birth to her son, Patrick. He would be raised by his grandparents for the first eight years of his life, with Cardinale passing him off as her younger brother. When she married Cristaldi in 1966, however, he welcomed Patrick into his home and gave him his surname.

With the press clamouring to see more of 'La fidanzata d'Italia' ('Italy's sweetheart'), Cristaldi dissuaded a post-natally depressed Cardinale from quitting films and rushed into her first lead, as Marisa, in Claudio Gora's romantic comedy, Three Strangers in Rome (1958). He also started to micromanage her life, so that 'I was no longer master of my own body or thoughts,' Cardinale later lamented. 'Even talking with a friend about anything that could make me look different from my public image was risky, as if it had been publicised, I would have been in trouble. Everything was in the hands of Vides.'

The plus point of being with Cristaldi, however, was that he only associated with the best directors and 1959 alone saw Cardinale work with Alberto Cavalcanti (Venetian Honeymoon), Luigi Zampa (The Magistrate), Nanni Loy (Fiasco in Milan), and Enzo Provenzale (Vento del sud). She came to Britain and was allowed to deliver her own dialogue, as Maria, the maid who comes between Michael Craig and Anne Heywood in Ralph Thomas's Upstairs and Downstairs. Frustratingly, this is currently out of reach, but Cinema Paradiso users can see Cardinale displaying a new maturity as Assuntina Jacovacci in Pietro Germi's The Facts of Murder (1959), in which the director also plays Inspector Ingravallo, who realises that everything is not as it seems when he is called to an address on Rome's Via Merulana to investigate a jewellery robbery.

Even more crucial to her evolution as an actress was the role of Barbara Puglisi, opposite Marcello Mastroianni as her impotent husband in Mauro Bolognini's Il bell'Antonio, which was adapted from a Vitaliano Brancati novel by Pier Paolo Pasolini and went on to win the prestigious Golden Leopard at the Lucano Film Festival. Reviewing the satire in The Village Voice, film-maker Jonas Mekas wrote, 'She is wild, and beautiful at moments, a sort of neo-B.B.' Indeed, the press started to call her 'C.C.' in imitation of her idol and Mastroianni fell head over heels during the shoot, only for Cardinale to keep him at arm's length, which she did with all co-stars who developed a crush. She was more taken with Bolognini, whom she called 'a great director, a man of rare professional capability, great taste and culture. Beyond that, for me personally, he was a sensitive and sincere friend.'

Her reputation was further bolstered as Pauline Bonaparte in Abel Gance's all-star historical epic, Austerlitz, which returned to the subject of his silent masterpiece, Napoléon (1927). Cardinale drew even warmer notices for playing Fedora Santini in Francesco Maselli's Silver Spoon Set, a comedy of manners that made he headlines when the censors insisted on removing a scene of Cardinale kissing Tomas Milian in bed, as it was deemed too racy. However, her most important role of 1960 saw her play Ginetta Giannelli, the fiancée of Vincenzo Parondi (Spiros Focás), in Luchino Visconti's Rocco and His Brothers, which teamed her for the first time with Alain Delon.

As we noted in our Instant Expert's Guide to Visconti, this neo-realist saga won the Special Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival. But not every noteworthy picture from this period has made it to disc in the UK, despite being highly prized in Italy. An example is Mauro Bolognini's The Lovemakers, in which 19th-century country girl, Bianca, finds herself working in a Florentine brothel, where she is protected by Amerigo (Jean-Paul Belmondo), the disgraced nephew of a wealthy family. However, we can bring you Valerio Zurlini's Girl With a Suitcase (both 1961), in which Cardinale drew on her own experiences as Aida Zepponi, a rootless singer and single mother who is forced to live by her wits after being dumped by her boyfriend. So compelling was her performance that Cardinale won the David di Donatello Award for Best Actress and she would remember her director with great affection. 'Zurlini was one of those who really love women,' she told a reporter. 'He had an almost feminine sensitivity. He could understand me at a glance. He taught me everything, without ever making demands on me...He was really very fond of me.'

After Cardinale had held her own against Danielle Darrieux and Michèle Morgan as Albertine Ferran in Henri Verneuil's The Lions Are Loose (1961), Cardinale reunited with Belmondo as Venus, the gypsy who is rescued by the dashing outlaw, Louis-Dominique Bourguignon, in Philippe de Broca's swashbuckling adventure, Cartouche (1962). The same year saw Cardinale upstage Anthony Franciosa and Betsy Blair as Angiolina Zarri, a woman with a past in 1920s Trieste in Mauro Bolognini's adaptation of Italo Svevo's acclaimed novel, Senilità (aka Careless, 1962). Evocatively photographed in monochrome by Armando Nannuzzi, this intense cross-class drama had Italian critics comparing Cardinale to Louise Brooks. But she was about to become an international star in her own right.

Home and Away

By 1963, Cardinale was regularly being compared in the press to Sophia Loren and Gina Lollobrigida. Yet, when two very different auteurs envisioned their ideal of Italian womanhood, they chose Cardinale to embody her. However, their shooting schedules overlapped, so Cardiinale had to keep shuttling between Rome and Sicily to make Federico Fellini's 8½ and Luchino Visconti's The Leopard (both 1963).

'It was hard doing both,' Cardinale recollected. 'Visconti wanted me dark-haired, for Fellini I had to be a blonde, I had long hair at the time and kept dyeing it from one to the other. The two directors were completely different, almost hated each other, I think, Visconti was a perfectionist, on set nobody could say a word unless instructed. Working for these two directors in these two films marked a turning point in my career.'

Fellini cast her as Claudia, an actress who proves to be the inspirational salvation of Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni), a film director who suffers from creative block while planning a science fiction picture. 'I only did one film with Fellini,' Cardinale enthused, 'but he made me feel the centre of the Earth, the most beautiful, the most important. I truly miss him, his sweetness, tenderness, his thin voice even. Acting for him was like an event, there was no script, the set was noisy, it was chaotic, anarchy reigned, yet he was able to isolate himself and get on with the job, you thought you were doing everything spontaneously, any which way was you pleased, but at the end of the day you'd done exactly what he had in mind.'

Cardinale was also grateful to Fellini for getting other directors to accept her raspy Italian rather than have her dubbed. 'When I arrived for my first movie,' she confessed, 'I couldn't speak a word. I thought I was on the moon. I couldn't understand what they were talking about. And I was speaking in French; in fact, I was dubbed. And Federico Fellini was the first one who used my voice. I think I had a very strange voice.'

By contrast with the monochrome spa that served as Fellini's backdrop, Visconti opted for lavish production values and rich colours in depicting the Sicily of Il Risorgimento that had been conjured in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa's epochal novel. It spoke volumes for Cardinale's burgeoning talent that she could switch so easily into the role of Angelica Sedara, the mayor's daughter who enchants both ageing prince, Don Fabrizio Corbera (Burt Lancaster), and his reckless revolutionary nephew, Tancrede Falconeri (Alain Delon). Indeed, not only did she have to play sharply contrasting characters, but she also had to adapt to markedly different working styles.

'With Fellini you have no script,' she divulged, 'it is all improvisation. When he was shooting, all the actors came to see him because he was magic. The set was like a circus, people shouting down phones. He couldn't shoot without noise. With Visconti, it was the opposite, like doing theatre. We couldn't say a word. Very serious.' She continued, 'Visconti was precise and meticulous, spoke to me in French.' As she told Danièle Georget for her memoir, 'You can learn beauty. Visconti taught me how to be beautiful. He taught me to cultivate mystery, without which, he said, there cannot be real beauty.'

Viewed now, it's hard to fathom that Cardinale changed persona every fortnight in order to give Fellini and Visconti what they wanted. The former claimed she had the face 'of a deer, or a cat, passionately lost in tragedy'. She also reminded him of 'a child who is already a woman, authentic and mysterious'. Visconti compared her to 'a cat lying on a sofa that makes you stroke it'. But, he warned, 'this cat can change into a tigress'. Feline or not, Cardinale gave each man what he needed and, in the process, helped 8½ win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, while The Leopard took the top prize at Cannes.

Wonderful though she is in both pictures, Cardinale's best performance in 1963 came as Mara Castellucci in Luigi Comencini's Bebo's Girl, an adaptation of a Carlo Cassola novel about a peasant girl in postwar Tuscany being torn between a troubled partisan (George Chakiris) and a sweet city boy (Marc Michel). As Cardinale won the Nastro d'Argento for Best Actress, this deserves to be much better known. But it contributed to Hollywood finally sitting up and taking notice.

She didn't have to go all the way to America for her first studio assignment, however, as Blake Edwards's The Pink Panther (1963) was shot in Italy. Cardinale played Princess Dala of Lugash, whose giant pink gemstone attracts the attention of suave cracksman, Sir Charles Lytton (David Niven), who is holidaying under the watchful eye of Inspector Jacques Clouseau (Peter Sellers) of the Sûreté, who suspects him of being the notorious Phantom. Although her voice was dubbed by Gale Garnett, Cardinale enjoyed her time on the set at Cortina d'Ampezzo, as Edwards was as animated as Fellini. She also struck up a rapport with Niven, who informed her, 'After spaghetti, you're Italy's happiest invention.'

In 1962, Cardinale had been interviewed by novelist Alberto Moravia, who had irritated her by focussing on her sex appeal. She had replied, 'I used my body as a mask, as a representation of myself,' and he had been so impressed by her composure that he based a character on her in his novel, The Goddess of Love. The pair's paths crossed again, two years later, when Cardinale played Carla Ardengo in Francesco Maselli's take on Moravia's Time of Indifference, which co-starred Paulette Goddard as her ageing countess mother and Rod Steiger as the opportunist who seeks to exploit them both when they fall on hard times.

An even bigger name from Hollywood's Golden Age would play Cardinale's mother in Henry Hathaway's Circus World (aka Magnificent Showman, 1964), as she essayed trapeze artist, Toni Alfredo, who has been raised by Matt Masters (John Wayne) following the disappearance of her aerialist mother, Lili (Rita Hayworth). Once again, Cardinale had to travel no further than Spain, but the picture's troubled development (that saw Nicholas Ray and Frank Capra leave the director's chair) disrupted a production that typified the growing gulf between Old Hollywood and the younger movie audience.

It also convinced Cardinale that she was better off staying in Europe than shackling herself to a studio on a long-term contract. 'I took care of my own interests,' she outlined years later, 'blankly refusing to sign an exclusive contract with Universal Studios. I only signed for individual films. In the end, everything worked out fine for me.' Elsewhere, she revealed: 'I don't like the star system. I'm a normal person. I like to live in Europe. I mean, I've been going to Hollywood many, many times, but I didn't want to sign a contract.' Not that it was always sweetness and light in Italy, as she disliked playing Maria Grazia in The Magnificent Cuckold (1964), as she didn't see eye to eye with director Antonio Pietrangeli (who would drown four years later at the age of 49), while co-star Ugo Tognazzi repeatedly tried to seduce her.

Moreover, journalist Enzo Biagi had discovered the truth about Patrick and persuaded Cardinale to tell all in articles published in Oggi and L'Europeo that sparked a debate about whether Cardinale had deceived her public or had been a victim doing the best for her child. She threw herself into making Sandra (1965) with Luchino Visconti, although the story of Sandra Dawdson, a Holocaust survivor who might have had an incestuous relationship with her brother (Jean Sorel), did little to calm the waters. As a consequence, she accepted Paul Newman's offer to borrow his house and spent the next two years in Hollywood.

It's been said that Cardinale was never as big a star as Sophia Loren or Gina Lollobrigida, even though she made probably made more artistically significant features than either of them. In truth, she was never a diva like her feuding compatriots. But, then again, she was never quite on an artistic par with Monica Vitti, who inspired partner Michelangelo Antonioni's best work in the 1960s. Certainly, Hollywood had little idea what to do with Cardinale.

In Philip Dunne's Blindfold (1965), she played Vicky Vincenti, who believes that psychiatrist Dr Bartholomew Snow (Rock Hudson), is part of the security conspiracy that prompted her brother's abduction. Next, she found herself down the cast list in Mark Robson's Lost Command (1966), which follows Basque Lieutenant Colonel Pierre-Noël Raspéguy (Anthony Quinn) and military historian Captain Phillipe Esclavier (Alain Delon) from French Indo-China to Algeria, where the latter falls for Aicha Mahidi (Cardinale), whose brother is involved with the National Liberation Front.

She was equally underused in Richard Brooks's The Professionals (1966), as marquessa Maria Grant is 'kidnapped' by Mexican revolutionary, Jesus Raza (Jack Palance), and her rancher husband (Ralph Bellamy) hires Bill Dolworth (Burt Lancaster), Rico Fardan (Lee Marvin), Hans Ehrengard (Robert Ryan), and Jake Sharp (Woody Strode) to bring her home. However, Cardinale was better served here than she was by Don't Make Waves (1967), a rare misfire by Scottish director Alexander Mackendrick that drew on Ira Wallach's 1959 novel, Muscle Beach, to follow the romantic entanglements of artist Laura Califatti, tourist Carlo Cofield (Tony Curtis), swimming pool tycoon Rod Prescott (Robert Webber), and California surfer, Malibu (Sharon Tate).

The death during production of freefall cinematographer Bob Buquor added to the sense of unease on the set. Moreover, Cardinale was involved in a tussle with Bob Dylan, who, without her permission, had used her image on the cover of his 1966 album, Blonde on Blonde, and it had to be removed from subsequent pressings. Such an episode confirmed Cardinale's feeling that Hollywood wasn't the place for her. During her American sojourn, she had befriended Rock Hudson, Barbra Streisand, Elliott Gould, and Steve McQueen. But she disliked being in a goldfish bowl and left for Italy with the words, 'If I have to give up the money, I give it up. I do not want to become a cliché.' She did have one regret, however. One night, Marlon Brando had called round and she had kept him on the doorstep. 'He said something about how we were both Aries,' she joked later. 'He was very charming and funny, but I was just laughing. I turned him away. But when I closed the door, I said to myself, "You are so stupid!"'

There's No Place Like Rome

In 1966, Cardinale returned to Italy to reunite with Mario Monicelli as an eccentric babysitter making life awkward for a hapless doctor in the 'Queen Armenia' episode of the comic anthology, Sex Quartet. It wasn't the high spot of her career, but it served the purpose of getting her out of Hollywood and she followed it with another freewheeling romp, as she played a nurse making her various boyfriends across Rio de Janeiro jealous in Franco Rossi's A Rose For Everyone (1967).

Such pictures reinforced the impression that Cardinale was the girl next door, with Life magazine defining 'the Cardinale appeal' as 'a blend of solid simplicity and radiant sensuality. It moves men all over the world to imagine her both as an exciting mistress and wife.' In another statement that was typical of the times, Anthony Quinn compared working with Cardinale and Sophia Loren. 'I relate easier to Claudia,' he told a reporter. 'Sophia creates an impression of something larger than life, something unobtainable. But Claudia - she's not easy, but still she's within reach.'

Actually, she wasn't. Despite the 14-year age difference, she had married Cristaldi in December 1966 after he had sprung a surprise wedding ceremony upon her during a trip to Atlanta. In fact, the union was never legally recognised in Italy, but Cristaldi continued to control Cardiinale's career and his judgement usually proved to be sound, as her 1968 output would suggest.

She started the year playing Rosa Nicolosi, a witness to a mob shooting in Damiano Damiani's adaptation of Leonardo Sciascia's ground-breaking novel about the Sicilian Mafia, The Day of the Owl. Cardinale won the Donatello for Best Actress, while co-star Franco Nero took the Best Actor award for his performance as Captain Bellodi, the cop from Northern Italy who takes on crime boss Don Mariano Arena (Lee J. Cobb).

Her next assignment took her to Egypt to play Elena, the mistress of Lee Harris (Harry Guardino) who comes to the aid of exploited USAF veteran, Brynie MacKay (Rod Taylor), in Joseph Sargent's debut feature, The Hell With Heroes. A reunion with Rock Hudson followed as Captain Mike Harmon helps jewel thief Esmeralda Marini burgle an Austrian villa in Francesco Maselli's comic caper, A Fine Pair. But her most iconic portrayal of the year came in Sergio Leone's Spaghetti masterpiece, Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), as New Orleans prostitute Jill McBain arrives in Flagstone to discover that her new husband (and father of three) has been murdered by an outlaw named Frank (Henry Fonda).

On her first day working with Fonda, Cardinale had to seduce him. 'It was very embarrassing for us both as the press were invited,' she later revealed. 'Henry admitted to me afterwards that it was the first time he had ever played a truly erotic scene in a film.' Adding to the pressure was the fact that new wife Shirlee was also on the set, with Cardinale telling La Monde that she 'stood behind the camera like a vulture, which completely paralysed me'.

Leone gave Jill an emblematic significance that biographer Robert C. Cumbow claimed was carefully calculated. 'Her sex-goddess appearance,' he wrote, 'combines with her more mystical iconographic associations to ease the progress of Jill from tart to town builder, from harlot to earth mother, from sinner to symbol of America - the apotheosis of the harlot with a heart of gold.' It was certainly one of Cardinale's most indelible displays, but it drew a line under her dalliance with transatlantic film-making. 'They invited anyone who was anyone in Europe,' she later reflected, 'obviously because they wanted to have a monopoly of the stars, but more often than not they destroyed you: you went to America and you came back and you were no longer anyone.'

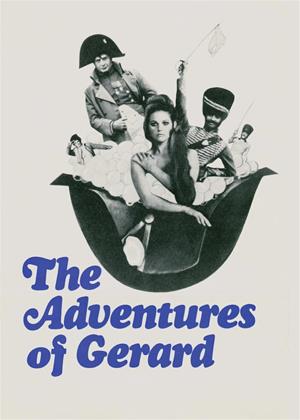

She didn't work with a non-European director for the next 14 years, following Marcello Fondato's Diary of a Telephone Operator and Luigi Magni's The Conspirators with Mikhail Kalatozov's The Red Tent (all 1969), an account of a disastrous 1928 bid to fly an airship over the Arctic Circle that co-starred Peter Finch as Italian pilot Umberto Nobile and Sean Connery as Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen. Her sole excursion in 1970 saw her essay the scheming Countess Theresa in exiled Pole Jerzy Skolimowski's The Adventures of Gerard, which co-starred Peter McEnery as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's dashing brigadier and Eli Wallach as Napoleon Bonaparte.

While Cardinale was content to be back in her homeland with her son, it made her career more difficult to follow, as infuriatingly few of her Italian releases made it off the festival circuit and into UK or US cinemas. Consequently, while one might expect minor offerings like Jean Vaudin's The Butterfly Affair (1971) and Antonio Calenda's One Russian Summer (1973) to be tricky to track down (despite the latter co-starring Oliver Reed), it's deeply frustrating that Cinema Paradiso can't bring users Cardinale's Donatello-winning turn as Carmela (a prostitute who bewitches Alberto Sordi) in Luigi Zampa's comedy A Girl in Australia; her earthy display as another prostitute, Aiché, in Marco Ferreri's Vatican satire, Papal Audience; and her much-cherished pairing with Brigitte Bardot, as Marie Sarrazin, the 1880s town boss of Bougival Junction in Christian-Jacques's The Legend of Frenchie King. Even Cardinale's reunion with Jean-Paul Belmondo, as gangland moll Georgia Saratov in La Scoumoune (both 1972), José Giovanni's crime saga set in 1930s Marseille, is off limits.

Fortunately, we can offer Cardinale's final liaison with Luchino Visconti, as she plays the wife of a Roman professor (Burt Lancaster) whose house is taken over by a countess (Dominique Sanda) and her retinue in Conversation Piece. From a personal point of view, however, Cardinale's teaming as Lucia Esposito with Franco Nero in the noirish poliziotteschi, Blood Brothers (both 1974), proved to be more significant, as she fell in love with Neapolitan director Pasquale Squitieri and left Cristaldi to move in with him. In spite of his neo-Fascist views, Cardinale had a daughter (also named Claudia) with Squitieri. Moreover, even though they conducted a long-distance relationship after she settled in Paris, they frequently worked together on L'arma, Father of the Godfathers (both 1978), the mini-series Naso di Cane (1986), Stupor mundi (1997), Li chiamarono...briganti! (1999), Élisabeth - Ils sont tous nos enfants (TVM, 2002), and Father (2011). Cinema Paradiso users can see the couple in tandem in The Iron Prefect (aka I Am the Law, 1977), in which 1920s Sicilian woman Anna Torrisi welcomes the mission of Il Duce's envoy, Cesare Mori (Giuliano Gemma), to tackle organised crime on the island. This fact-based drama shared the Donatello for Best Film with Luigi Magni's In the Name of the Pope King, while Cardinale would go on to win the Nastro d'argento for Best Actress for her performances in two more Squitieri features, as Clara Petacci, opposite Fernando Briamo's Benito Mussolini, in Claretta (1984), and as addict's mother Elena, alongside Bruno Cremer, in Act of Contrition (1990).

Such was Cristaldi's fury at being dumped that he sought to convince his fellow producers to blackball Cardinale. Undaunted, she tried her hand at becoming a disco diva, as 'Love Affair' and 'Sun...I Love You' charted across Europe and in Japan. But she continued to act, notably playing anti-Fascist firebrand, Libera Volente, in Mauro Bolognini's Libera, My Love, before teaming twice with Monica Vitti, as Gabriella Sansoni in Marcello Fondato's The Immortal Bachelor and as Laura in Carlo Di Palma's Blonde in Black Leather (all 1975). As with her performance as Armida Ballarin in Alberto Sordi's comedy, A Common Sense of Modesty, these roles were little seen outside Italy and France. But millions watched Cardinale as the woman taken in adultery in Franco Zeffirelli's acclaimed New Testament mini-series, Jesus of Nazareth (both 1976), which starred Robert Powell in the title role.

Also available to rent is Damiano Damiani's political thriller, Goodbye & Amen (1977), in which Aliki De Mauro is taken hostage in her Rome hotel room by sniper Donald Grayson (John Steiner), who is trying to prevent CIA agent, John Dhanny (Tony Musante), from orchestrating a coup in an African republic. And, while Cardinale's teamings with Michel Piccoli in Étienne Périer's Fire Share and Alan Bridges's Little Girl in Blue Velvet (both 1978) elude us for now, we can also present George P. Cosmatos's Escape to Athena (1979), which sees resistance fighter Zeno (Telly Savalas) and brothel madam, Eleana (Cardinale), ally with Professor Blake (David Niven) to keep some priceless Byzantine artefacts out of the clutches of Major Otto Hecht (Roger Moore), the antique-collecting commandant of a POW camp on a Greek island. This stellar actioner may not be a classic, but it rattles along and boasts an uncredited cameo from William Holden cracking a gag about his Oscar-winning turn in Billy Wilder's Stalag 17 (1953).

A Busy Grande Dame

Although Cardinale headlined Roberto Faenza's Si salvi chi vuole (1980), as Luisa Morandini, the film was barely seen outside Italy and this set a pattern for much of Cardinale's work for the last four decades of her career. She might cameo alongside Franco Nero, Anthony Quinn, and Christopher Lee in Peter Zinner's The Salamander (1981), but this take on a Morris West novel was strictly Italian genre fare.

Old friends Marcello Mastroianni and Burt Lancaster awaited her Princess Consuelo Caracciolo in The Skin (1981), Liliana Cavani's uncompromising account of the liberation of Naples at the end of the Second World War that earned Cardinale the Nastro d'Argento for Best Supporting Actress. Yet it proved less arduous than Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo (1982), in which Cardinale played Molly, the Peruvian brothel keeper who helps Irishman Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald (Klaus Kinski) purchase the steamship he needs to tap the rubber reserves that he hopes will make him rich enough to realise the dream of building an opera house in the Amazonian rainforest.

A born adventurer, Cardinale enjoyed the hardship of her 'survival battle to live...in a location out of this world'. Indeed, she called it 'the best adventure of my life' and Werner Herzog was lost in admiration for the way in which she coped with her infamously unpredictable co-star. 'She was such a good element to bring Kinski to his senses sometimes,' he once opined. 'She was such a good comrade. I think that she was one of the one or two female partners that he ever respected.' Anyone wanting to know more about this remarkable shoot and its extraordinary star should check out Les Blair's Burden of Dreams (1982) and Herzog's My Best Fiend (1999).

Also in 1982, Cardinale played Antonella Defour in Michel Lang's sex comedy, Bankers Also Have Souls. She also appeared in recycled footage as Princess Dala in Blake Edwards's Trail of the Pink Panther before later rejoining him to essay Maria Gambrelli, the mother of Inspector Jacques Clouseau's gendarme heir, in Son of the Pink Panther (1993), which starred Roberto Benigni. The character had originally been played by Elke Sommer in A Shot in the Dark (1964).

In only her second television venture, Cardinale played Anabelle de Fourdemont Valensky in Waris Hussein's take on Judith Krantz's bestseller, Princess Daisy (1983), which featured Ringo Starr and Barbara Bach in supporting roles. Sadly, nothing else that Cardinale made over the next decade is available on disc in the UK, even though she reunited with Marcello Mastroianni as Matilda in Marco Bellocchio's adaptation of Luigi Pirandello's Henry IV (1984). Other notable assignments included two directed by French women, Nadine Trintignant's Next Summer (1985) and Diane Kurys's A Man in Love (1987), while Cardinale also portrayed Marie Antoinette's court favourite, Yolande de Polastron, in the feted bicentennial two-parter, La Révolution française (1989).

Now based on Paris, Cardinale also starred in Mayrig (1991), Henri Verneuil's film about the aftermath of the 1915 Armenian genocide, and its sequel, 588 rue paradis (1992). She also worked with a number of Maghrebi film-makers, including Moroccan Souheil Ben-Barka (The Battle of the Three Kings, 1990), Tunisian Férid Boughedir (Summer in La Goulette, 1996), and French-Algerian Rachida Krim (Sous les pieds des femmes, 1997). Cinema Paradiso members can see her play Sara, a protective Tunisian mother in Mahdi Ben Attia's The String (2009). However, 30 year-old son, Malik (Antonin Stanly), returns home after the death of his father in France and proceeds to break his mother's heart by falling for her estate handyman (Salim Kechiouche).

Having played Teresa Viola in Alastair Reed's four-part BBC adaptation of Joseph Conrad's Nostromo (1996), Cardinale was paired with Jeremy Irons, as Madame Falconetti, in Claude Lelouch's And Now...Ladies and Gentlemen (2002). In her early sixties, she also embarked upon a stage career and contributed to numerous documentaries. As she told Variety a few years later, 'The thing I find most disturbing these days is that as soon as an actress hits 60, she gets thrown in the trash, with very few exceptions. I'm 79 and I keep working, but I don't care about money. What I care about is helping directors who are starting out.' Her attitude resulted in the Venice Film Festival presenting Cardinale with its Golden Lion for lifetime achievement in 1993, alongside Roman Polanski, Robert De Niro, and Steven Spielberg. Four years later, she was presented with a career David at the Donatello Awards.

She also picked up an honorary Golden Bear at the 2002 Berlin Film Festival and the Golden Orange for Best Actress at the 47th Antalya Film Festival for her performance as Enrica, an elderly Italian woman who takes in a young Turkish exchange student in Ali Ilhan's Signora Enrica (2010). At one point, she delivers the line: 'I was a bombshell. My breasts were better than Claudia Cardinale's.' Back in France, Cardinale received the Legion of Honor before playing Jean Dujardin's mother in Nicole Garcia's A Look of Love (2010), Jeanne Moreau's friend in 104 year-old Portuguese auteur Manoel de Oliveira's final film, Gebo and the Shadow, and painter Jean Rochefort's concerned wife in Fernando Trueba's The Artist and the Model (both 2012), which is set in Occupied France in 1943.

An aesthete's obsession also informs Richard Laxton's Emma Thompson-scripted historical drama, Effie Gray (2014), which saw Cardinale play a chaperoning viscountess opposite Greg Wise's John Ruskin and Dakota Fanning's Euphemia Gray. The same year saw her cast as Nuria Calzolari, the mother of two daughters living in the South Tyrol on the outbreak of war between Italy and Austria-Hungary, in Ernest Gossner's 1915: The Battle For the Alps (aka The Silent Mountain, 2014).

Cardinale returned to the United States for the role of Signora Morosini in Nadia Szold's thriller, Joy de V. (2013), in which a con artist's schemes unravel when his pregnant wife goes missing. Alas, the Cinema Paradiso catalogue parts company with Cardinale with Ella Lemhagen's All Roads Lead to Rome (2015), in which she played Raoul Bova's Tuscan mother, Carmen, opposite Sarah Jessica Parker's journalist single mom. But she made five more films in her final decade, including Antonio Pisu's black wartime comedy, Nobili Bugie (2017), which cast her as an avaricious duchess who offers sanctuary to three Jews in order to steal their gold ingots, and her swan song, Ridha Behi's The Island of Forgiveness (2022), which took her back to Tunisia to play Agostina, the mother of an academic who has made his career in Rome.

Despite having separated from Squitieri, Cardinale mourned his passing on 18 February 2017. Later the same year, she found herself embroiled in a brouhaha when the Cannes Film Festival touched up a 1959 photo of her dancing on a Rome rooftop for the poster for the 70th festival. 'This image has been retouched,' she explained, 'to accentuate this effect of lightness and transpose me into a dream character. This concern for realism has no place here and, as a committed feminist, I see no affront to the female body. There are many more important things to discuss in our world. It's only cinema.'

Cardinale had been a UNESCO goodwill ambassador for the Defence of Women's Rights since 2000 and she was always ready to guide young actresses. 'If you want to practice this craft,' she revealed in 2014. 'you have to have inner strength. Otherwise, you'll lose your idea of who you are. Every film I make entails becoming a different woman. And in front of a camera, no less! But when I'm finished, I'm me again.' On another occasion, she declared, 'Never take on a role that will hurt you or make you sell out. And refuse to accept the awful caprices of certain directors or any form of professional blackmail. Yes, you need to fight!' She also warned against disrobing for the camera. 'I never felt scandal and confession were necessary to be an actress. I've never revealed myself or even my body in films. Mystery is very important.'

A tomboy to the end - 'I don't spend hours in beauty parlours' - Claudia Cardinale died on 23 September at her home in Nemours in the Île-de-France. She was 87 and had graced the screen for 69 of those years. An arthouse darling with the common touch, she will never be forgotten, despite the scarcity of UK releases of her award-winning Italian pictures. Perhaps her greatest achievement, however, was to regain control of her life from the men who had tried to exploit her (whether they loved her or not). Maybe the 80th anniversary poster for Cannes can celebrate those women who have challenged male supremacy in cinema from the silent age to the #MeToo era?

-

Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958) aka: I Soliti Ignoti

1h 49min1h 49min

1h 49min1h 49minCarmelina Nicosia (Claudia Cardinale) lives with her controlling brother, Michele (Tiberio Murgia), who belongs to a band of incompetent thieves planning a heist that includes petty thief Mario (Renato Salvatori), opportunist Peppe (Vittorio Gassman), baby-minding photographer Tiberio (Marcello Mastroianni), and ageing pickpocket, Capannelle (Carlo Pisacane).

- Director:

- Mario Monicelli

- Cast:

- Vittorio Gassman, Marcello Mastroianni, Renato Salvatori

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

Girl with a Suitcase (1961) aka: La ragazza con la valigia / Pleasure Girl

2h 1min2h 1min

2h 1min2h 1minSingle mother Aida Zepponi (Cardinale) leaves her musician boyfriend to be with Marcello Fainardi (Corrado Pani), a wealthy aristocrat whose teenage brother, Lorenzo (Jacques Perrin), develops a crush on the stranger and vows to help her.

- Director:

- Valerio Zurlini

- Cast:

- Claudia Cardinale, Jacques Perrin, Luciana Angiolillo

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

8½ (1963) aka: Otto e mezzo / Eight and a Half

Play trailer2h 18minPlay trailer2h 18min

Play trailer2h 18minPlay trailer2h 18minWhile suffering a creative block and being berated by the various women in his life, film director Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) decides that an actress named Claudia (Cardinale) is the embodiment of his Ideal Woman. However, she suggests that his inability to create is rooted in his reluctance to love.

- Director:

- Federico Fellini

- Cast:

- Marcello Mastroianni, Anouk Aimée, Claudia Cardinale

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

The Leopard (1963) aka: Il Gattopardo

Play trailer2h 58minPlay trailer2h 58min

Play trailer2h 58minPlay trailer2h 58minAs Giuseppe Garibaldi's Red Shirts threaten the peace in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1860, both Don Fabrizio Corbera, Prince of Salina (Burt Lancaster), and his nephew, Tancredi Falconeri (Alain Delon), fall for the daughter of the mayor, Angelica Sedara (Cardinale, who also doubles as her own mother).

- Director:

- Luchino Visconti

- Cast:

- Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon, Claudia Cardinale

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

The Pink Panther (1963) aka: La pantera rosa

Play trailer1h 53minPlay trailer1h 53min

Play trailer1h 53minPlay trailer1h 53minKeen to keep the giant pink gemstone gifted by her father before she was forced to flee Lugash, Princess Dala (Cardinale) sides with gentleman thief, Sir Charles Lytton (David Niven), rather than French police inspector, Jacques Clouseau (Peter Sellers).

- Director:

- Blake Edwards

- Cast:

- David Niven, Peter Sellers, Robert Wagner

- Genre:

- Comedy, Children & Family, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

The Day of the Owl (1968) aka: Mafia / Il giorno della civetta

Play trailer1h 48minPlay trailer1h 48min

Play trailer1h 48minPlay trailer1h 48minRosa Nicolosi (Cardinale) is wary of collaborating with mainland cop, Captain Bellodi (Franco Nero), when her husband disappears after they witness the murder of a truck driver who had crossed the line with Sicilian crime boss, Don Mariano (Lee J. Cobb).

- Director:

- Damiano Damiani

- Cast:

- Claudia Cardinale, Franco Nero, Lee J. Cobb

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) aka: C'era una volta il West / There Was Once the West

Play trailer2h 39minPlay trailer2h 39min

Play trailer2h 39minPlay trailer2h 39minFormer New Orleans prostitute, Jill McBain (Cardinale), arrives in Flagstone to discover that her new rancher husband (and father of three), has been gunned down on the orders of an outlaw named Frank (Henry Fonda).

- Director:

- Sergio Leone

- Cast:

- Henry Fonda, Charles Bronson, Claudia Cardinale

- Genre:

- Classics, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

The Iron Prefect (1977) aka: Il prefetto di ferro / I Am the Law

Play trailer1h 50minPlay trailer1h 50min

Play trailer1h 50minPlay trailer1h 50minFearful for her son's future, Anna Torrisi (Cardinale) supports no-nonsense 1920s prefect, Cesare Mori (Giuliano Gemma), when he's dispatched by Mussolini to the Sicilian town of Gengi to challenge the supremacy of the local mafia.

- Director:

- Pasquale Squitieri

- Cast:

- Giuliano Gemma, Claudia Cardinale, Stefano Satta Flores

- Genre:

- Drama, Thrillers, Action & Adventure, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Fitzcarraldo (1982) aka: Фіцкарральдо

Play trailer2h 31minPlay trailer2h 31min

Play trailer2h 31minPlay trailer2h 31minPeruvian brothel keeper, Molly (Cardinale), sells a steamboat to eccentric Irish investor Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald (Klaus Kinski) who hauls it overland in the hope of making enough from rubber tapping to build an opera house in the Amazon rainforest.

- Director:

- Werner Herzog

- Cast:

- Klaus Kinski, Claudia Cardinale, José Lewgoy

- Genre:

- Drama, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

The String (2009) aka: Le Fil

Play trailer1h 30minPlay trailer1h 30min

Play trailer1h 30minPlay trailer1h 30minSara (Cardinale) hopes that son Malik (Antonin Stahly) will settle down and have a family when he returns from France to her estate in the beachfront Tunis district of La Marsa. But he falls, instead, for Bilal the handsome handyman (Salim Kechiouche).

- Director:

- Mehdi Ben Attia

- Cast:

- Claudia Cardinale, Antonin Stahly-Vishwanadan, Salim Kechiouche

- Genre:

- Drama, Romance, Lesbian & Gay

- Formats:

-