On the day cinema marked its 130th anniversary, it lost one of its most distinctive stars. Despite being labelled 'a sex kitten' in the media, Brigitte Bardot helped change the way women were depicted on screen. During a lengthy retirement from acting, Bébé devoted herself to animal rights. However, as Cinema Paradiso discovers, she also held some controversial views that should prompt us to question her legacy.

Brigitte Bardot recorded more songs (60) than she made features (46). Yet she remained the ultimate French film star, even though she didn't set foot on a set for the last 52 years of her life. During this period, her outspoken opinions kept her in the headlines and tarnished her reputation. But she didn't care what anyone thought of her or her views. B.B. (or 'Bébé' as she was known in her heyday) did things her own way. After all, the intellectuals who had feted her in the 1950s had insisted, she was 'not so much a girl, as an exciting philosophical attitude'.

Bardot had no illusions about her acting talent. 'I don't think I was a good comedian,' she told one reporter. 'I contented myself to express what people asked me to interpret, and giving it my best.' Many of the tributes written since her death at the age of 91 have dismissed the majority of her films. But their quality matters less than their significance. They helped change the tone of French cinema during the so-called 'Tradition of Quality' period that Cinema Paradiso covered in a Brief History article. Moreover, they established Bardot as a cultural icon, whose clothes, hairstyle, make-up, and liberated attitude had a seismic impact upon the psyche of a country still coming to terms with the divisive realities of the Nazi Occupation. With the eyes of the world upon her, Bébé gave France its pride back. By the time she died, however, the country no longer felt so proud of a reluctant star who, for a short period in the 1950s, was the most famous woman in the world.

Poor Little Rich Girl

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot was born in the Parisian district of Passy on 28 September 1934. Father Louis was an engineer whose wealth came from a network of factories manufacturing liquid gas and acetylene. The daughter of an insurance company director, mother Anne-Marie (née Mucel) had servants and an English governess to help run the family's nine-bedroom apartment at 1 Rue de la Pompe, in the luxurious 16th arrondissement. Brigitte and younger sister Marie-Jeanne (aka Mijanou) felt stifled in the atmosphere of strict Catholic conservatism which made visits to their indulgent paternal grandparents so important, as they had a large garden at 17 rue du Général Leclerc in Louveciennes, which was a reconstruction of a chalet that had been imported from Norway for the 1889 Exposition Universelle.

As Brigitte suffered from amblyopia in her left eye, she was cossetted by her parents, who considered her something of an ugly duckling beside her more gifted sister. Educated at home, she had few childhood friends and was confined to the apartment for much of the Occupation. When she started dancing to records to cheer herself up, her mother was sufficiently impressed to engage a private ballet tutor from the Paris Opera. At the age of seven, Brigitte was enrolled at Cours Hattemer, where she spent three days a week when not having dance lessons under her mother's supervision at a local studio.

When they were still quite young, Brigitte and Mijanou smashed a valuable vase while hiding under a table. Mother-and-son writer-directors

Danièle and Christopher Thompson recreated this incident in their 2023 mini-series, Bardot, which was shown on Channel Four at the end of 2025. However, while they showed the girls being told to address their parents by the formal term 'vous' rather than the more familiar 'tu' in order to teach them some respect for their elders, the Thompson's didn't show them being whipped 20 times each. In her memoirs, Bardot cited this as the moment she decided to rebel against her staid upbringng.

In 1949, she was accepted into the Conservatoire Nationale de Danse, where she trained for three years under the exiled Russian choreographer, Boris Knyazev. She was also sent to study at the the Institut de la Tour, an exclusive Catholic high school, where she felt like an outsider because of her sheltered background and her body image. At the age of 14, however, Brigitte (much to her own surprise) suddenly started to blossom.

Ballet School Dropout

With her daughters growing, Anne-Marie Bardot opened a hat shop for an elite clientele. In order to promote a new line, she arranged for Brigitte and her fellow dance students to pose as mannequins. She was spotted and referred to Hélène Gordon-Lazareff, the director of the magazines Elle and Le Jardin des Modes. who offered the 14 year-old a chance to do some modelling. On 8 March 1950, Bardot appeared on the cover of Elle and was invited by director Marc Allégret to audition for his proposed adaptation of Édouard Dujardin's 1887 novel, Les Lauriers sont coupés. As she was nervous, Allégret suggested that she read the scene with his young assistant, Roger Plemiannikov, the son of Ukrainian immigrants who was known by his middle name, Vadim.

The film was never made, but Bardot and Vadim were immediately smitten with one another and he arranged with her parents to give her acting lessons at their apartment, having told Anne-Marie, 'It would be fascinating to take your daughter and make it seem as if she has gone completely off the rails.' Eventually, however, Bardot started bunking school to spend afternoons at the tiny flat Vadim shared with actor Christian Marquand.

Writing for Paris Match while he worked on film ideas. Vadim arranged for Bardot to be represented by Olga Horstig-Primuz, the influential Yugoslavian-born agent who would play a key role in making her client an international icon. Bardot's parents were appalled by the idea of her becoming an actress, however, although her grandfather had bluntly informed them, 'If this little girl is to become a whore, cinema will not be the cause.' Louis Bardot threatened to kill Vadim after discovering their illicit romance. However, plans to send Bardot to school in Britain were hurriedly dropped after she tried to gas herself in the kitchen oven and her parents agreed to let the couple see each other twice a month before they would be allowed to marry after Bardot's 18th birthday. Convinced that they could make great films together, Vadim (who was six years her senior) agreed to the terms and Bardot continued with her education before dropping out of ballet school to take acting lessons with René Simon.

Bardot earned 200,000 francs for debuting as Javotte Lemoine, the scheming cousin trying to prevent Bourvil from inheriting an inn in Normandy, in Jean Boyer's Le Trou normand (aka Crazy For Love). Shortly before she married at Notre-Dame-de-Grace de Passy on 20 December 1952, Bardot even got to act with Vadim, as they played a couple witnessing a wedding in Daniel Gélin's Les dents longues (aka The Long Teeth). But her most significant picture of 1952 was Willy Rozier's Manina (aka Manina, la fille sans voile), in which the 17 year-old Bardot wore a bikini that almost resulted in the film being banned under the Production Code in the United States, as showing a woman's navel was forbidden. Nobody seemed to mind that co-star Jean-François Calvé (who played a treasure-seeking student) wore a tight pair of swimming trunks that left little to the imagination. The film became a sensation in France after Bardot posed on the beach at the Cannes Film Festival, but it didn't reach the UK until 1959, when it was released as The Lighthouse Keeper's Daughter.

Cinema Paradiso users can see what all the fuss is about for themselves, but it's not currently possible to watch Bardot's performances as Domino in André Berthomieu's Le Portrait de son père (aka His Father's Portrait, 1953), Mademoiselle de Rozille in Sacha Guitry's Si Versailles m'était conté (aka Royal Affairs in Versailles), Anna in Mario Bonnard's Tradita (aka Concert of Intrigue, both 1954), Pilar d'Aranda in Jean Devaivre's Le Fils de Caroline chérie (aka Caroline and the Rebels), or Sophie in Marc Allégret's Futures vedettes (aka School For Love, both 1955), which teamed her flirtatious student with tempted teacher Jean Marais. Even Anatole Litvak's Act of Love (1953) is out of reach, even though it was made with Hollywood money and starred Kirk Douglas as a soldier looking back on his wartime encounter with orphan Dany Robin.

Bardot had a bit part as Mimi, but her second English-language outing did much more to raise her profile, as the British tabloids went to town after she played nightclub singer Hélène Colbert opposite Dirk Bogarde's Simon Sparrow in Ralph Thomas's Doctor At Sea (1955). The French press also started to take notice when veteran director René Clair cast Bardot as Lucie in his first colour film, Les grandes manoeuvres (aka Summer Manoeuvres). She plays the daughter of a provincial photographer (Raymond Cordy), whose chaste fin-de-siècle romance with Félix Leroy (Yves Robert) contrasts with the lustier entanglement involving cavalry lieutenant Armand de la Verne (Gérard Philipe) and Parisian divorcée, Marie-Louise Rivière (Michèle Morgan).

Clair tapped into the melancholy that Bardot often felt off screen and a few serious critics picked out her performance. However, she was declared 'a virtuoso of décolletage' after playing femme fatale Olivia Marceau in Georges Lacombe's La Lumière d'en face (aka The Light Across the Street), a knock-off of James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice, which had been filmed by Tay Garnett in 1946. Raymond Pellegrin and Roger Pigaut played the diner-owning husband and the mechanic lover who gets ensnared in Bardot's wicked schemes. This should be on disc, but we can bring you Bardot as Andraste in Robert Wise's runaway production of Helen of Troy (both 1956), an adaptation of the Trojan War story from Homer's Iliad that stars Rossana Podestà and Jacques Sernas as Helen and Paris.

During the course of 1956, Bardot also essayed Brigitte Latour in Michel Boisrond's Cette sacrée gamine (aka Mam'zelle Pigalle), Poppaea Sabina in Steno's Mio figlio Nerone (aka Nero's Mistress), and Agnès Dumont in Marc Allégret's En effeuillant la marguerite (aka Plucking the Daisy). The peplum picture proved notable because the brunette Bardot decided to dye her hair blonde rather than wear a wig and she liked the results so much that she never went back. Just as significantly, the first and third titles were co-scripted by Roger Vadim. But it was to be his other 1956 collaboration that would send Brigitte Bardot into the stratosphere.

Et Dieu...créa la femme (aka And God Created Woman, 1956). However, producer Raoul Levy had been impressed with his screenwriting and asked him to adapt a book by lawyer Maurice Garçon. Disliking The Little Genius, Vadim wrote an original storyline that had been inspired by the trial of a young woman who had murdered a man after having slept with his two brothers. Levy realised that the racy narrative would run into trouble with the censors, but Harry Cohn at Columbia was intrigued by Bardot and thought the picture might put a chink in the armour of the Production Code that had restricted free expression in Hollywood since 1934.

From the opening shot of Juliette Hardy (Bardot) lying naked on her stomach under the Saint-Tropez sun, it was obvious that Vadim was seeking to shake up not just cinematic convention, but also conservative French attitudes. An 18 year-old orphan who refuses to conform to the rules set by her guardians, Juliette bounces between Eric Carradine (Curt Jürgens), an ageing playboy who wants to build a casino on the waterfront, and the Tardieu brothers whose shipyard stands in his way, Antoine (Christian Marquand), Michel (Jean-Louis Trintignant), and Christian (Georges Poujouly). The plot is strictly, if slickly, melodramatic, but Vadim photographed both the idyllic locale and his footloose wife with a naturalism and energy that made the picture seem so spontaneous and subversive.

The scene of Bardot dancing barefoot to calypso music epitomised the freshness of Vadim's approach, as did the nonchalance of Bardot's performance, as Juliette pouted, tousled her long blonde hair, and lived for the moment on her own terms. Many accused Vadim of subjecting Bardot to the camera's 'male gaze', but he also succeeded in presenting a woman who embraced her sexual desires and saw nothing wrong in taking what she wanted. In an age when screen heroines were supposed to seek true love and remain chaste while awaiting the all-important marriage proposal, this was a groundbreaking statement about female sexuality in general and the temperament of Brigitte Bardot in particular.

As the media in 1956 wasn't quite ready for such an emancipated woman, they turned Bardot into a 'sex kitten'. When the film was released in the United States, Time magazine called her the 'Countess of Come-Hither', while a publicity shoutline ran, 'and God created woman…but the devil invented Brigitte Bardot'. Lengthy negotiations with Production Code chief Geoffrey Shurlock led to certain cuts being made, but American audiences just getting over Ingmar Bergman's Summer With Monika (1953) had never seen anything quite like this. Neither had the Vatican, who barred Catholics from viewing the film. Nevertheless, in taking $4 million, it became the highest-grossing subtitled import in US box-office history.

Bardot had made no secret of the fact that she didn't enjoy making films. But she was proud of her husband getting to direct and felt at home in her Saint-Tropez surroundings, as her parents owned a holiday home nearby. However, Bardot so relaxed into the role of a rebel without a care that she embarked upon an affair with Jean-Louis Trintignant - who was married at the time to Stéphane Audran - and separated from Vadim as soon as the shoot ended. They divorced the following year. but remained friendly. He has often been accused of being a Svengali who manipulated the vulnerable Bardot to achieve his own ends. But the Thompson mini-series is more sympathetic in its depiction without shying away from the fact that Bardot had been underage at the start of their sexual relationship. Vadim would later marry Jane Fonda - directing her in Barbarella (1968) - and would cast Rebecca De Mornay in his 1988 variation on the debut theme, And God Created Woman, which was set in Santa Fe and had critics rolling their eyes. Back in 1956, however, the influential Cahiers du Cinéma writer, François Truffaut (who became a leading figure in the nouvelle vague that would transform world cinema just a few years later) enthused, 'I thank Vadim for having made this young woman repeat, in front of the lens, everyday gestures - trivial gestures like playing with her sandal, or less trivial ones like, yes indeed, making love in broad daylight.' Truffaut knew that Et Dieu…créa la femme was, in essence, a saucy cinematic novelette. But he also recognised that the director and his co-conspirational star had dared to do something audaciously different and that there was now no going back for either film or the new mood of permissiveness that would come to flourish in the ensuing decade.

Beside the Seaside

Although she seemed to be an overnight sensation, the 22 year-old Bardot was actually a veteran of over a dozen features. Never before, however, had she been feted by such haute couturiers as Christian Dior, Pierre Cardin, and Pierre Balmain. Similarly, her every word and move had not previously been reported by the press. But stories about Bébé sold newspapers, as young women sought to emulate her gingham skirts and knitted sweaters with Bardot necklines, her long, kohl'd eyelashes, and her distinctively mussed 'choucroute' mane, while men of all ages indulged in various shades of fantasy and moral guardians across the social spectrum fulminated about her immodesty and immorality.

Although she detested being pursued by the paparazzi, Bardot was happy to pose for such trusted photographers as Sam Lévin and Cornel Lucas, who not only captured her pouting glamour, but also her mood of defiance and disdain for the media circus that was burgeoning around her. She had little desire to meet her fans and struggled to cope with the feeling of being hunted and trapped. Never close to her parents and resentful of their favouritism towards her sister, she had few friends beside agent Olga Horstig-Primuz and body double Maguy Mortini. Hence, she sought excitement and security through her love life, which fascinated reporters and readers far more than her films.

After Preston Sturges's claim to be directing Bardot in the unmade Long Live the King, she signed up to play Catherine Ravard in Pierre Gaspard-Huit's adaptation of Odette Joyeux's La Mariée est trop belle (aka Her Bridal Night, 1956), in which a country girl becomes a supermodel after she is discovered by magazine editor Michel Bellanger (Louis Jourdan), who is too preoccupied to realise that 'Chouchou' has fallen love with him. It's an amusing romcom, but Bardot spent the shoot lobbying government ministers to prevent Trintignant from being sent to Algeria during his national service.

Another established name was chosen to co-star in Michel Boisrond's La Parisienne (1957), a reworking of an 1885 Henry Becque play about the daughter of the French president and her dalliances with her father's womanising chief of staff and a visiting dignitary. Charles Boyer played Prince Charles, while Henri Vidal was Michel Legrand, who is forced to marry Bardot's Brigitte Laurier after they are caught in a compromising position at her father's country residence. The following year, which saw Bardot become the highest-paid actress in French film history. she surprised many by reuniting with Vadim on Les Bijoutiers du clair de lune (aka The Night Heaven Fell, 1958). Based on a novel by Albert Vidalie, the story set in rural Spain is brazenly melodramatic, as Ursula (Bardot) leaves a convent to live with her Aunt Florentine (Alida Valli), who becomes so jealous of her niece's friendship with younger lover, Lambert (Stephen Boyd), that she refuses to give him an alibi when he kills Comte Miguel de Ribera (José Nieto) in a tussle over Ursula.

Bardot's own private life seemed equally complicated. Taken by the Riviera, she had bought Le Castelet, a 14-bedroom 16th-century villa in Peymeinade, not far from Cannes. However, she also wanted a simple retreat near Saint-Tropez and acquired La Madrague, a blend of boathouse and fisherman's shack that needed connecting to the water, gas, and electricity mains. Yet it was tucked away from prying eyes at the end of a dirt road leading to the Bay of Canoubiers, although Bardot was so freaked by fans getting into her bedroom and stealing her underwear that she bought a second hideaway. La Garrigue. which would eventually become home to her menagerie of animals. For more about Bardot's time on the south coast, see Heinz Bütler's Riviera Cocktail (2006), which profiles Irish photographer Edward Quinn, who was renowned for capturing the likes of Cary Grant, Sophia Loren, Grace Kelly, Pablo Picasso, and Bardot during their stays on the Côte D'Azur.

Bored while fiancé Trintignant was in barracks, Bardot struck up a friendship with married crooner, Gilbert Bécaud. They became lovers after she recorded a spot for his New Year special and they made plans to watch the show together in her Paris apartment. When he failed to show, Bardot took an overdose and was only found after Bécaud became concerned after a midnight phone call. He invited her to join him on tour, but she grew frustrated at being hidden away backstage to avoid adverse publicity and alienating his fans. Learning little from the episode, Bardot became infatuated with another singer, Sacha Distel, and they remained an item until she began an on-set affair with actor Jacques Charrier. They married in Louveciennes on 18 June 1959 after Bardot had discovered she was pregnant. She tried to obtain an illegal abortion, but her fame meant that no doctors would risk the procedure and she found it difficult to bond with son Nicolas-Jacques after he was born on 11 January 1960.

Her claims about this phase of her life were disputed by the Charriers after the publication of her memoirs and this isn't the place to speculate about the whys and wherefores. Seeking solace in affairs with actors Glenn Ford and Sami Frey, Bardot remained deeply unhappy and the 26 year-old took an overdose and slashed her wrists in 1960 and almost died because the paparazzi blocked the ambulance taking her to hospital in Nice. When the chemist who had sole her the pills was questioned, he replied, 'I serve a hundred Bardots every day.'

Such shocking incidents did little to shake the nation's obsession with Bardot, which only made her ordeal all the more entombing. Yet, in her 1959 essay, 'Brigitte Bardot and the Lolita Syndrome', Simone de Beauvoir claimed that Bardot was the most liberated Frenchwoman ever. She called her a 'locomotive of women's history' whose on-screen assurance and allure challenged 'the tyranny of the patriarchal gaze'. However, she concluded that her bid to change how society felt about gender had been a 'noble failure' because she always seemed inaccessible in a slightly frivolous manner that was detached from everyday reality. Bardot didn't believe it was her job to be a role model or a trend-setter. When once asked whether her lifestyle was feminist, she replied, 'Absolutely not. Though men can be beasts, women's lib is idiotic.'

Enter the Auteurs

As so many of Bardot's later films are unavailable on disc in the UK, it makes sense to focus first on her work for some of the biggest names in French cinema. Although she had impressed under the tutelage of René Clair, the majority of her early films had been made by journeymen who remain little known outside their native France. Claude Autant-Lara, however, was renowned for his literary adaptations, although Cinema Paradiso users can only sample his sole British outing, The Mysterious Mr Davis (1939), and the religious satire, L'Auberge rouge (aka The Red Inn, 1951), which was scripted by Truffaut's 'Tradition of Quality' bêtes noires, Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost. They were also responsible for turning George Simenon's In Case of Emergency into Autant-Lara's En cas de malheur (aka Love Is My Profession, 1958), which cast Bardot as Yvette Maudet, a petty thief who hitches up her skirt in a bid to persuade leading lawyer André Gobillot (Jean Gabin) to represent her when she's caught robbing a watch-maker's shop with a toy gun.

Producer Raoul Levy had to work hard to mollify both Autant-Lara and Gabin, as Bardot was distracted during the shoot by her private problems. Nevertheless, she gives an effective display of calculating coquettishness and, having cameo'd as herself in Jean Cocteau's Le Testament d'Orphée (aka The Testamant of Orpheus), she was on equally good form when she collaborated with the formidable Henri-Georges Clouzot on La Vérité (aka The Truth, 1960).

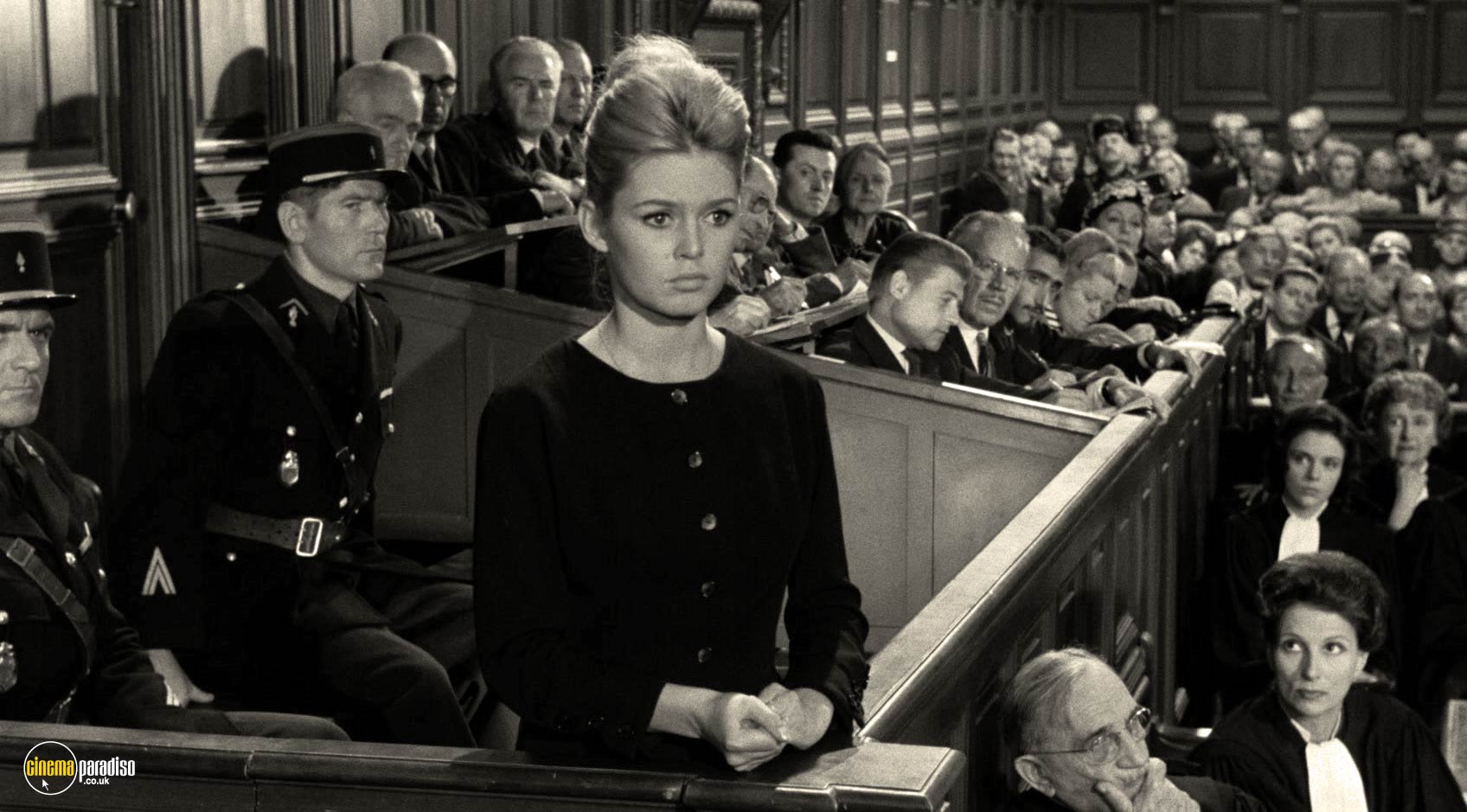

Flashing back from the discovery of Dominique Marceau (Bardot) beside the body of dead lover Gilbert Tellier (Sami Frey), the action returns to the courtroom, where lawyers Guérin (Charles Vanel) and Éparvier (Paul Meurisse) respectively seek to prove her innocence or guilt. As anyone who has seen L'Assassin habite au 21 (aka The Murderer Lives At 21, 1942), Le Corbeau (1943), Quai des Orfèvres (1947), Le Salaire de la peur (aka The Wages of Fear, 1953), and Les Diaboliques (1955) will know, Clouzot was a master of suspense in the grand Hitchcockian manner. But he was also a martinet on the set and treated Bardot abominably to elicit the performance of which he believed she was capable. In addition to stamping on her bare feet and slapping her across the face (she once retaliated), he also insisted on her taking sleeping pills (he told her they were painkillers) to disorientate her for a scene. By all accounts, she was still dazed two days later. But the tyrannical antics resulted in the film being nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. Moreover, during a period of almost tragic off-screen turmoil, it earned Bardot the David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Actress and La Vérité remained the only film of which she was proud. 'Clouzot harassed me and cut me up in every possible imaginable way', she wrote later. 'But I understood it was for the film, and not just stupid sadism.'

The picture was a huge box-office success in France, but the cinematic landscape was changing and the auteurs of the nouvelle vague sought out Bardot to give their modish features some mainstream appeal. The first to reach out was Louis Malle, a member of the so-called Left Bank group of film-makers that also included Alain Resnais, Jacques Demy, Agnès Varda, and Chris Marker. Having made his name with Ascenseur pour l'échafaud (aka Lift to the Scaffold, 1958) and Les Amants (1959), he cast Bardot as Jill opposite Marcello Mastroianni in Vie privée (aka A Very Private Affair, 1962), which was far from subtly based on Bardot's own experiences of fame, heartbreak, and extreme emotional distress.

This much-debated film is not on disc in this country, which is a shame, as Henri Decaë's colour photography is sublime. But it also offers intriguing insights into the Bardot myth and the misery that it caused her. Many critics have accused Malle of exploiting the actress's troubles, but he clearly recognised the effect that being in the public glare was having on Bardot and his aim was to critique the film industry, the media, and the public for prioritising the demands they made on her over her well-being.

Jean-Luc Godard thought along similar lines in presenting Camille Javal in Le Mépris (aka Contempt, 1963). However, Bardot had been cast as a last resort in this adaptation of Alberto Moravia's 1954 novel, Il disprezzo (aka A Ghost At Noon), as Godard had been thwarted in his plans to cast as the feuding screenwriter and his bored wife either Frank Sinatra and Kim Novak or Marcello Mastroianni and Sophia Loren. Monica Vitti also turned down the part, so Bardot was paired with Michel Piccoli alongside Jack Palance as the philistinic American producer in Europe to make a film of Homer's The Odyssey with legendary Austrian director, Fritz Lang (playing himself).

In fact, the film riffed on the tensions within Godard's own marriage to Danish muse Anna Karina and he only added the celebrated opening shot of a nakedly recumbent Bardot after the picture had wrapped at the insistence of American producer Joseph E. Levine, who thought it would make the film an easier sell Stateside. However, Godard used it to satirise the way in which Bardot was viewed, as Piccoli comments on her body with analytical cynicism. As critic Jean-Louis Bory wrote, 'I don't know what conditions the movie was made under, nor if Bardot and Godard even got along. But the result is clear: There has rarely been such a profound understanding between an actress and a director.'

In 1966, Bardot made an uncredited cameo as herself in the café scene in Godard's Masculin Féminin. This treatise on 60s pop culture focussed on the efforts of Jean-Pierre Léaud's demobbed soldier to impress yé-yé singer Chantal Goya. The script references Bob Dylan, who had dedicated the first song he had ever written to Bardot and had mentioned her in the lyrics to 'I Shall Be Free' on The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. The Beatles were also huge fans, with Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr listing her as their favourite actress in a New Musical Express questionnaire in 1963. Even though he would hang a large framed photograph of Bardot on a wall at Kenwood, John Lennon capriciously selected Juliette Greco. However, he and Paul tried to meet Bardot when they first went to Paris and had to be contented with a large box of bonbons because she was in Brazil. The band hoped to coax her into appearing in their follow up to Richard Lester's A Hard Day's Night (1964) and were thrilled when producer Walter Shenson proposed a comic version of The Three Musketeers, with Bardot as Milady de Winter. The plan never came to fruition, although Lester did make The Three Musketeers (1973) and The Four Musketeers (1974). Lennon finally got to meet the woman whose picture had adorned the ceiling of his teenage bedroom when press agent Derek Taylor arranged a hook-up at the Mayfair Hotel in London in May 1968. With McCartney in Scotland and Harrison and Starr declining the invitation, a nervous Lennon took a tab of LSD to calm himself down. Unfortunately, Bardot had not been informed that the other three Beatles were not coming and had invited friends to make up a dinner party at a posh restaurant. Unable to speak French, Lennon managed only to say 'hello' when they shook hands and felt too bashfully spaced out to go to Parkes. However, he stayed at the hotel with Taylor and eventually obliged Bardot with a couple of songs when she handed him a guitar.

Rather ungallantly, Lennon later dismissed the encounter by saying, 'I was on acid, and she was on her way out.' Bardot was included in McCartney's original sketch for the cover of Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967). But pop artist Peter Blake replaced her with Diana Dors. Several other film stars did make the cut, however, including Mae West, W.C. Fields, Fred Astaire, Leo Gorcey and Huntz Hall (of The Bowery Boys), Tony Curtis, Tommy Handley, Marilyn Monroe, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, Max Miller, Marlon Brando, Tom Mix, Tyrone Power, Johnny Weissmuller, Shirley Temple, Bobby Breen, and Marlene Dietrich.

Back in 1965, Bardot reunited with Louis Malle for Viva Maria!, in which she played Irish republican anarchist Marie Fitzgerald O'Malley, who seeks sanctuary in the circus wagon of Maria (Jeanne Moreau), a French vaudeville performer who just happened to be touring Central America in 1907 when Maria II lost her father in a bid to blow up a bridge. Having formed a double act, they accidentally invent the striptease when Maria II's dress rips before joining Flores (George Hamilton) in an effort to overthrow the dictatorial regime in San Miguel. Inspired by Robert Aldrich's Vera Cruz (1954), Malle sought to make 'a sort of burlesque boxing match - sexpot v seductress'. Thanks to the spirited playing of Bardot and Moreau, he just about succeeded in creating a female buddy movie that provided a link in a chain between Howard Hawks's Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) and Jacques Rivette's Céline et Julie vont en bateau (aka Céline and Julie Go Boating, 1974). By the time this was released, however, Bardot's film career had already ended.

She had received a BAFTA nomination for Best Foreign Actress for her work and agreed to team up with Malle for a final time after he had failed to persuade the producers to cast Florinda Balkan in the 'William Wilson' episode of Histoires extraordinaires (aka Spirits of the Dead, 1968), a portmanteau inspired by the writings of Edgar Allan Poe that also included Roger Vadim's 'Metzengerstein' (which starred Jane Fonda) and Federico Fellini's 'Toby Dammit', which centred on Terence Stamp. Bardot appears as Giuseppina Ditterheim, a courtesan who spends an evening in 19th-century Bergamo playing cards with an army officer (Alain Delon) who is haunted by his doppelgänger. During the course of the vignette, she sheds her clothes and is verbally abused and viciously whipped. But most reviews focussed on the outrage that France's blonde bombshell had been made to sport a sleek black wig.

The Long Fade

Despite having become the first star to feature in America's annual box-office Top 10 on the strength of subtitled films, Bardot refused all entreaties to work in Hollywood. As a consequence, the majority of her films were made for a French audience and not all of them travelled well. The knock-on effect can be felt by British viewers six decades later, as only a handful of the titles she headlined in the 1960s and 1970s are available on disc.

Having ventured to Seville to play Eva Marchand for veteran director Julien Duvivier in La Femme et le pantin (aka The Female), Bardot came to RAF Abingdon in Oxfordshire to take a parachute course to prepare her for Babette s'en va-t-en guerre (aka Babette Goes to War, both 1959), which was the picture on which she met Jacques Charrier. Set during the Second World War, this rousing CinemaScope adventure centred on a young woman who crosses the Channel by boat, only to return to help the Free French fight the Nazis. David Niven and Gérard Philipe had been mentioned as possible co-stars, with Roger Vadim being named as the original director after his plan to team Bardot and Frank Sinatra in Paris By Night had fallen through. Producer Raoul Levy (who had struck a three-picture deal with Columbia) decided that Vadim wouldn't be right for an action movie and went for Christian-Jaque, who was best known for the swashbuckling classic, Fanfan la Tulipe (1954).

Reuniting with Michel Boisrond, Bardot played loyal wife Virginie Dandieu in Voulez-vous danser avec moi? (aka Come Dance With Me, 1959), a thriller based on the Kelley Roos novel, The Blonde Died Dancing that turned on a blackmail attempt on a small-town dentist and a murder at a dance studio. An uncredited cameo followed as a restaurant patron in Henri Verneuil's Affaire d'une nuit (aka It Happened All Night, 1960). But this proved to be a tempestuous year, in which Bardot's relationship with Charrier broke down and she was lucky to be found in a field after another suicide attempt. When she returned to acting, Vadim was at the helm of La Bride sur le cou (aka Please, Not Now!), in which Sophie enlists the help of her doctor friend, Alain (Michel Subor), when she suspects that reporter boyfriend Philippe (Jacques Riberolles) is cheating on her with wealthy American, Barbara (Josephine James). The film notoriously featured a dance in which Bardot wore nothing but a body stocking, but she was more modestly attired for the 'Agnès Bernauer' episode of Boisrond's Les Amours célèbres (aka Famous Love Affairs, both 1961), in which she was accused of witchcraft by the disapproving father (Pierre Brasseur) of Albert III, the 17th-century Duke of Bavaria (Alain Delon).

Vadim came calling again with Le Repos du guerrier (aka Love on a Pillow, 1962), which was adapted from a sombre realist novel by Christiane Rochefort, in which independent Parisienne, Geneviève Le Theil, becomes besotted with Renaud (Robert Hossein), the penniless alcoholic she meets while collecting her inheritance in Dijon.

As Bardot refused to go to Hollywood, American productions came to her, with the French-speaking Anthony Perkins being her co-star in Édouard Molinaro's adaptation of Charles Exbrayat's novel, Une ravissante idiote (aka The Ravishing Idiot, 1964), in which Penelope Lightfeather (aka Agent 0038-24-36) tries to help and hinder Russian spy Harry Compton in his bid to learn about NATO troop movements. Partially shot in Britain, this Cold War spoof demonstrated Bardot's underused gift for comedy. But she was confined to a walk on as herself in Henry Koster's Dear Brigitte (1965), a take on John Haase's novel, Erasmus With Freckles, which sees poetry professor James Stewart and wife Glynis Johns strive to persuade their eight year-old son (Billy Mumy) to stop writing love letters to B.B.

Following a cameo in Antoine Boursellier's Marie Soleil (aka Sunshine Marie), Bardot married German millionaire Gunter Sachs on 14 July 1966, after he had used a helicopter to drop 12,000 roses on her home. She told waiting reporters on her return to play Cécile in Serge Bourguignon's À coeur joie (aka Two Weeks in September, 1967), 'The honeymoon was marvellous, but I don't mind going back to work. It's good to have a change - honeymoon, work, honeymoon, work.' The Anglo-French romcom flopped and the couple separated in 1968 before divorcing on 7 October 1969. Preferring to hide away in Saint-Tropez, Bardot turned down the chance to make pictures with Marlon Brando and Steve McQueen, with Faye Dunaway taking the role of Vicki Anderson in Norman Jewison's The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). She also gifted Diana Rigg the part of Tracy Di Vicenzo opposite George Lazenby in Peter R. Hunt's On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969).

Bardot did keep a date with 007, however, when she was cast as Countess Irina Lazaar opposite Sean Connery and Honor Blackman in Edward Dmytryk's Shalako (1968), a Western based on a novel by Louis L'Amour that was filmed at Shepperton Studios and in the Tabernas Desert in the Andalusian province of Almería. Jack Hawkins, Stephen Boyd, and Peter Van Eyck were also in a starry line-up that included Woody Strode as the Apache warrior who wants to keep strangers off his lands in 1880s New Mexico. The film did brisk business, which significantly helped the Bardot coffers, as she was on a 12.5% share of the profits on top of her $400,000 fee. But she never made another non-French film, turning down the role of Didi in Elia Kazan's adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Last Tycoon (1974).

So frequently was Bardot's Clara déshabillé in Jean Aurel's sex comedy, Les Femmes (aka Women, 1969), that the Italian censors demanded extensive cuts. The film did poorly at home, although she had more luck as Felicia, the much-divorced socialite who sets out to seduce cellist Jean-Pierre Cassel after bumping into him in her car in Michel Deville's L'Ours et la poupée (aka The Bear and the Doll). Throughout her career, Bardot had resisted reteamings with big-name actors and had only rarely been paired with a female co-star. However, Annie Girardot gave her a run for her money as Mona Lisa, the Parisian prostitute who befriends runaway nun, Agnès, in Les Novices (aka The Beginner, both 1970), which was co-directed by Guy Casaril and Claude Chabrol, who had married Jean-Louis Trintignant's ex-wife, Stéphane Audran.

Now, we're not saying that these later Bardot outings were classics, but they are undemandingly entertaining, as is Robert Enrico's Boulevard du Rhum (aka Rum Runners), an adaptation of a Jacques Pecheral novel that sees bootlegger Cornelius von Zeelinga (Lino Ventura) abandon crime after he becomes obsessed with silent film star Linda Larue. Christian-Jaque's Les Pétroleuses (aka The Legend of Frenchie King, both 1971) also rattles along, even though contemporary critics didn't have a good word to say about outlaw's daughter Louise allying with Bougival Junction bigwig, Marie Sarrazin (Claudia Cardinale), to deliver the 1880s Texan town from its chauvinistic menfolk.

After a year-long hiatus, in which Bardot was seen in archive footage in Pierre Tchernia's Le viager (aka The Annuity, 1972), she joined forces with Roger Vadim for the final time on Si Don Juan était une femme... (aka Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman). Vadim said of the project, 'Underneath what people call "the Bardot myth" was something interesting, even though she was never considered the most professional actress in the world. For a few years, since she has been growing older and the Bardot myth has become just a souvenir, I wanted to work with Brigitte. I was curious in her as a woman, and I had to get to the end of something with her, to get out of her and express many things I felt were in her. Brigitte always gave the impression of sexual freedom - she is a completely open and free person, without any aggression. So I gave her the part of a man - that amused me.' However, during the shoot, Bardot declared, 'If Don Juan is not my last movie it will be my next to last.' She proved as good as her word, as she never acted again after L'Histoire très bonne et très joyeuse de Colinot Trousse-Chemise (aka The Edifying and Joyous Story of Colinot, both 1973), the story of a 15th-century runaway (Francis Huster) learning how to survive after being offered shelter by the resourceful Arabelle. Curiously, this was the only picture Bardot made that was directed by a woman, Nina Companéez.

Throughout her career, Bardot had repeatedly threatened to quit films. However, agent Olga Horstig-Primuz and producer Raoul Levy had kept persuading their meal ticket to stick to what she knew. By 1973, however, the 39 year-old believed that 'Everything felt ridiculous, superfluous, absurd and useless.' Drinking heavily, she was also exhausted by the toll that fame had taken on her. 'When you live such intense moments as I have done,' she later wrote, 'there is always a bill to pay.' Although she never actually announced her retirement, she told a reporter on the set that she had had enough and wanted her life back. In her memoirs, she confided, 'It felt like a huge weight was lifted off my shoulders.'

How It All Turned Sour

Bardot might only have acted for 20 years, but she remained a film star for the rest of her life. She strove to use her fame to help the cause to which she devoted her last five decades, the welfare of animals. As she came to identify with the politics of the far right, however, some of her public statements were deemed to be legally unacceptable and many came to feel that they left an indelible stain upon her reputation.

Such was the level of press intrusion into every facet of Bardot's existence that her actions were forever being judged by the often unforgiving French public. Her love life came in for particular scrutiny. By her own account, she had 17 romantic relationships and moved on whenever 'the present was getting lukewarm'. As she wrote in her candid memoir, 'I have always looked for passion. That's why I was often unfaithful. And when the passion was coming to an end, I was packing my suitcase.'

Having parted company with Sacha Distel, Bardot lived with musician Bob Zagury in the mid-1960s before marring Gunter Sachs. Prone to falling for her leading men, she dated Patrick Gilles, her co-star in The Bear and the Doll, and Laurent Vergez, with whom she made Don Juan. She resisted Sean Connery's attempts at seduction, however, claiming 'I wasn't a James Bond girl!' In a 2018 interview with Le Journal du Dimanche, she also denied rumors that she had been intimate with Johnny Hallyday, Jimi Hendrix, and Mick Jagger.

Always insecure about her looks, Bardot sought reassurance from her partners and ditched them when she needed fresh validation. Among her lovers in this period were ski instructor Christian Kalt, nightclub owner Luigi Rizzi, writer John Gilmore, actor Warren Beatty, artist Miroslav Brozek, and TV producer Allain Bougrain-Dubourg. When the latter left her, Bardot attempted suicide on her 49th birthday.

She also faced criticism because of her comments on motherhood after stating, 'I'm not made to be a mother. I'm not adult enough - I know it's horrible to have to admit that, but I'm not adult enough to take care of a child.' There was outrage when she wrote that her son was a 'cancerous tumour' and that she would have 'preferred to give birth to a little dog'. The revelation that she had frequently punched herself in the stomach during her pregnancy was also decried, as was the fact she barely saw her son during his childhood. In 1997, Bardot was sued by Jacques and Jacques-Nicolas Charrier for her account of their time together, with a judge ordering her to pay £17,000 and £11,000 to her ex-husband and son respectively for her hurtful remarks. In 2018, however, Jacques-Nicolas (who was now a grandfather based in Norway) revealed that he was getting on better with his mother and that they visited each other once a year.

Bardot never repaired her relationship with Charrier, however, who had once complained 'You can't have for yourself what belongs to the nation, whether its B.B. or camembert.' Curiously, a magazine editor had once said, 'We should be as proud of B.B., as of Roquefort cheese and the wine of Bordeaux.' President Charles de Gaulle called her 'the French export as important as Renault cars'. He had fallen from power by 1969, but negotiations had started the previous year for Bardot to pose as Marianne, the spirit of French liberty whose portrait or bust could be found in every official building across the country. She was the first to be accorded the honour and has since been followed by Michèle Morgan, Catherine Deneuve, Mireille Mathieu, Laetitia Casta, and Sophie Marceau.

In 1974, Andy Warhol produced eight paintings of Bardot, who had just posed nude for Playboy to mark her 40th birthday. This spread clearly qualified Bardot for a 2005 Kenny Dixon documentary, whose name we won't mention here, but which can be found by clicking this link. A quarter of a century after this shoot, Bardot trailed only Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, and Raquel Welch in Playboy's 100 Sexiest Stars of the Century poll and she has since featured prominently in numerous other listings. Despite often posing provocatively, Bardot proved bashful when she recorded 'Je t'aime...moi non plus' in 1967 with Serge Gainsbourg, with whom she had the seemingly inevitable fling. Some of their other recordings can be enjoyed on Brigitte Bardot: Divine B.B. (2004), but she managed to keep her breathy performance under wraps until 1986, by which time Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin had scored a controversial international hit with their 1968 recording. When the Bardot version was released for download in 2006, it became the third most popular track of the year.

This was 33 years after Bardot had stopped making movies. But she remained as famous and as enticing as ever. Recognising this, she used her place in people's hearts to champion the cause of animals. In 1977, Bardot met Paul Watson, the founder of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society and he invited her to pose on an ice floe with some seal pups to publicise the barbarity of Canadian culling methods.

A year after she had received the Legion of Honour, she launched the Fondation Brigitte Bardot and started campaigning against wolf hunting, bullfighting, the fur trade, battery farming, the sale of horse meat, and animal testing. She became a vegetarian and raised three million francs by auctioning off her jewellery and other valuables (including the dress in which she had married Roger Vadim) to fund the organisation. Indeed, she became so vocal in the media that she had an anti-whaling ship named after her. 'I can understand hunted animals because of the way I was treated,' she once said. 'What happened to me was inhuman.' On another occasion, she added, 'I gave my beauty and my youth to men and now I am giving my wisdom and experience, the best of me, to animals.'

Her opinions brought negative publicity and even death threats. But she repeatedly wrote to government ministers demanding action and even sent a letter to Chinese leader, Jiang Zemin, in 1999, to complain about his nation's 'torturing bears and killing the world's last tigers and rhinos to make aphrodisiacs'. In 2010, she told Queen Margrethe II of Denmark that the killing of dolphins in the Faroe Islands 'is not a hunt but a mass slaughter...an outmoded tradition that has no acceptable justification in today's world'. However, she accused President Emmanuel Macron of lacking courage when it came to protecting wildlife and, as a result, he was not invited to her funeral and the family turned down a proposed national celebration of Bardot's life.

Such principled stances were more than laudable and earned Bardot accolades from UNESCO and PETA. She had a right to be proud, when she announced that her foundation had 'financed the construction of a wild animal hospital in Chile, as well as a park to care for mistreated bears in Bulgaria, for koalas in Australia, for elephants in Thailand, and for horses in Tunisia. If the foundation wasn't active, a great many species conservation programmes would be non-existent.'

But her remarks on the dhabihah method of halal butchering and the Jewish shechita method of ritual slaughtering overstepped the mark and she was fined for her comments.

Her views became increasingly right-wing after 16 August 1992, when she married Bernard d'Ormale, whom she once described as 'intelligent, straight, romantic, sensitive' and possessing 'the character of a pig'. He was a former advisor to Front National leader Jean-Marie Le Pen and, during their time together, was fined twice for public insults and five times for inciting racial hatred. She shrugged off the incidents by saying, 'I never knowingly wanted to hurt anybody. It is not in my character.' But comments in her two volumes of autobiography, Initiales B.B. (1996) and Pluto's Square (1999), suggested otherwise, with the 'Open Letter to My Lost France' section of the latter complaining that 'my country, France, my homeland, my land' had been 'invaded by an overpopulation of foreigners, especially Muslims'. She would later write: 'They slaughter women and children, our monks, our civil servants, our tourists and our sheep, one day they'll slaughter us, and we'll have deserved it.'

More of the same followed in her 2003 tome, Un cri dans le silence, in which she attacked illegal immigrants, Muslims, interracial marriage, the LGBTQ+ community, women in politics, teachers, and the long-term unemployed before calling for a return of the guillotine. As recently as 2019, the eightysomething Bardot was convicted of claiming that the Hindu Tamils of the French Indian Ocean territory of Réunion, had 'the genes of savages' and 'reminiscences of cannibalism'. Even her views on the #MeToo movement ruffled feathers, as she insisted that the claims made by actresses of being sexually harassed and abused were 'hypocritical, ridiculous, without interest'. She even told Paris Match, 'Many actresses flirt with producers to get a role. Then when they tell the story afterwards, they say they have been harassed...in fact, rather than benefit them, it only harms them.' Shortly afterwards, Saturday Night Live featured a sketch in which Catherine Deneuve (Cecily Strong) despairs of Bardot (Kate McKinnon) shouting, 'Free Harvey Weinstein!', and declares, 'Brigitte is very old and very wrong.' Unrepentent, the 90 year-old Bardot told a TV interviewer in May 2025, 'Feminism isn't my thing. I like guys,' before going on to complain: 'Those who have talent and put their hands on a girl's buttocks are relegated to the bottomless pit. We could at least let them continue to live. They can no longer live.'

It's hard to watch Bardot's films without these invidious ideas on race, religion, and toxic masculinity coming to mind. Yet, in a free country, she had a perfect right to declare Marine Le Pen 'the Joan of Arc of the 21st century' in endorsing her for the presidency. It's also possible to understand Bardot's misanthropic views through such pronouncements as 'People get on my nerves'; 'I detest humanity, I'm allergic to it'; and 'Humans have hurt me. Deeply. And it is only with animals, with nature, that I found peace.' Even more revealing was the admission, 'My life has been a succession of brief moments of joy and terrible trials. With me, life is made up only of the best and the worst, of love and hate. Everything that happened to me was excessive.'

Danièle and Christopher Thompson capture this sense of a woman being buffeted by fate and trapped in a nightmare she can't escape in Bardot. Laetitia Casta had briefly played Bébé in Johan Sfar's Gainsbourg: A Heroic Life (2010), but Julia de Nunez was given more scope to trace the evolution of Bardot's personality in a mini-series that chronicles her life from the first meeting with Roger Vadim to the 1960 suicide attempt. When the project was first mooted, Mme Thompson revealed that Bardot had 'answered with a very long letter, saying that she was always surprised how unbelievably interested people were in her and did not quite understand why she was not left alone for good'. However, as Thompson's parents, director Gérard Oury and actress Jacqueline Roman, had been Bardot's friends, she declared (even if she didn't exactly give her blessing) that Thompson was better placed than most to give a fair account of her travails.

Although Bardot had survived breast cancer in the mid-1980s, she underwent two operations after a new diagnosis in the autumn of 2025. She died at La Madrague on 28 December 2025 at the age of 91. President Macron paid fulsome tribute: 'Her films, her voice, her dazzling glory, her initials, her sorrows, her generous passion for animals, her face that became Marianne, Brigitte Bardot embodied a life of freedom. French existence, universal brilliance. She touched us. We mourn a legend of the century.'

A quirk of fate meant that she passed on the day marking the 130th anniversary of cinema, as she had long renounced her moment in the spotlight. 'The other day,' she said, 'I came across And God Created Woman on TV, which I haven't seen in ages. I told myself that that girl wasn't bad. But it was like it was someone other than me. I have better things to do than study myself on a screen.' At another time, she declared, 'For me, the cinema is linked with such a circus in my life that I don't want to ever hear it talked about.' Noting how the likes of Marilyn Monroe and Romy Schneider had died alone, she declared: 'The majority of great actresses met tragic ends. When I said goodbye to this job, to this life of opulence and glitter, images and adoration, the quest to be desired, I was saving my life...I was really sick of it.' On another occasion, she had confided about the furore around Et Dieu…créa la femme, 'All my life, during that film, and before and after, I was never what I wanted to be, which was frank, honest, and straightforward. I wasn't scandalous - I didn't want to be. I wanted to be myself. Only myself.'

There's a sad irony in the fact that Brigitte Bardot was probably happier in herself during the period for which she has been vilified in so many posthumous press pieces. As she said in 1996, 'The madness which surrounded me always seemed unreal. I was never really prepared for the life of a star. I'm happier in my routine life today than when I was chased after by 100 photographers.' She continued, 'You mustn't think I am dissatisfied. That would be a form of bitterness. My life is now what I always wanted - what I dreamed about subconsciously.' Her childhood had been controlled by her parents, her youth by Roger Vadim and Raoul Levy. For the next two decades, she belonged to France and eventually the world. It was only after she retired from the screen and devoted herself to a cause she passionately believed in that she started to find peace. A lasting relationship also provided security to go with the sanctuary. Unfortunately, this partnership emboldened her to share opinions that most found reprehensible. Her stance tarnished her reputation - but she wouldn't have cared, as she had no affection for the Bébé years because she had no control over her life, her career, or her image. This is perhaps why she invested so much time, money, and emotion into her animals, as they made no demands.

Had she died young like Monroe or Schneider, Bardot would have been enshrined as an icon of feminist cinema, for, as scholar Ginette Vincendeau has said, she was 'a pioneer figure in the representation of women' who had 'represented a dream of emancipation'. But her screen career had long been over by the time Bardot claimed in her final book, My BB Alphabet (which was published shortly before her death) that Marine Le Pen's National Rally was the 'only urgent remedy to the agony of France', which she insisted had become 'dull, sad, submissive, ill, ruined, ravaged, ordinary and vulgar'.

Had Bardot not been such a significant cultural figure, we would not have been aware of such noxious opinions. Sadly, however, we are and her legacy will forever be tainted as a consequence.