As Julie Christie turns 85, Cinema Paradiso reflects on a screen career unlike any other.

Soon after becoming a film star in the mid-1960s, Julie Christie realised she didn't like what was happening to her. Feeling exploited and objectified within a male-dominated industry, she decided only to take projects that coincided with her political interests and/or which enabled her to work with film-makers who intrigued her.

Former partner and three-time co-star Warren Beatty claimed Christie was 'the most beautiful and at the same time the most nervous person I had ever known'. Yet, few have been more assertive in operating within the film business on their own terms. As a result, Christie has succeeded in distancing herself from popular conceptions of stardom while managing to remain relevant by responding to change and using her status to promote causes and issues that matter to her. In other words, she has acted and advocated while staying true to herself.

From Assam to Sussex

Julie Frances Christie was born on 14 April 1940 at the Singlijan Tea Estate at Chabu in the Indian state of Assam. Her father, Frank, managed the plantation of the Jokai Tea Company and she grew up here with her mother, Rosemary, and her younger brother, Clive. The marriage was not a happy one, however, as Frank had fathered another daughter, June, with an Indian tea picker.

As her parents were prominent members of the expat community, Julie was often left with her ayah (or nanny), who used to tie her to a tree when she was naughty so that the tigers could get her. Keen for their daughter to receive the best education, her parents sent her to the convent school at Loreto. However, they were also concerned by the situation in the country, as India moved towards independence.

Shortly after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in January 1948, Rosemary and Julie returned to Britain, where the latter was billeted with her grandmother in Brighton. She didn't last long at her first school, as she was expelled for telling a rude joke about a man returning to a train compartment after a comfort break with his fly open. As her grandmother was finding it a strain to look after her, Julie was enrolled as a boarder at the Convent of Our Lady School in St Leonards-on-Sea.

When this arrangement failed to work out, Rosemary sent her daughter to Wycombe Court School in Buckinghamshire and advertised for a foster mother. Julie became fond of her doting Aunt Elsie and also settled in at Wycombe Court, where she enjoyed playing a swashbuckling cavalier in a school play before taking the part of the Dauphin in a production of George Bernard Shaw's Saint Joan (which would be filmed by Otto Preminger in 1957, with Jean Seberg in the lead).

With the divorced Rosemary now living in rural Wales, Julie spent the holidays with her. She passed seven O Levels, but did so badly in French that her mother sent her to live with a family in Tarbes near Pau in order to master the language at a finishing school. On her return, Julie started studying for her A Levels at Brighton Technical College. Here, she was encouraged to follow her ambition to act by her first boyfriend, Joel. Both the Old Vic in Bristol and the Central School of Speech and Drama in London offered her a place, but she chose the latter as she thought life in the capital would be more exciting.

In fact, it proved to be exhausting. As Frank owned a tea plantation, Christie was deemed too affluent for a student grant and she spent her time crashing with classmates on an inflatable mattress that became her most prized possession. Between classes, she became hooked on French cinema and longed to be cast in a nouvelle vague film. Because of her looks, however, she wasn't always taken seriously by her tutors, with one reducing her to tears by informing her that she didn't need to learn how to act, as her face would always look good on camera. A producer from the BBC appeared to agree, as he watched her play the lead in a Central School staging of The Diary of Anne Frank (which had been filmed by George Stevens in 1959 ) and offered her a role that would get her seen in every household in Britain with a television.

Breaks and Mistakes

In 1961, Christie debuted on the small screen as Ann in an episode of Call Oxbridge 2000, which had been spun off from the popular medical soap, Emergency Ward Ten (1957-67), which had already spawned Robert Day's 1959 feature, Life in Emergency Ward Ten. However, she made considerably more impact as Christine, the dark-haired assistant to scientist John Fleming (Peter Halliday), whose laboratory believes it has made contact with an alien civilisation in A For Andromeda (1961), a BBC science-fiction serial that was co-written by cosmologist Fred Hoyle. Christie reprised her secondary role - as the blonde biological construct known as Andromeda 6 - in the 'Cold Front' episode of the sequel series, The Andromeda Breakthrough (1962). This is available to rent from Cinema Paradiso, along with surviving fragments from the original series, as part of The Andromeda Anthology (2006).

Taken aback by her experience in a studio, Christie felt the need to hone her skills on stage and she took herself off to Essex. Frinton Summer Theatre has been called 'The Nursery of the Stars' because actors of the calibre of Michael Denison, Vanessa Redgrave, Jane Asher, Anthony Sher, Gary Oldman, and David Suchet got their starts there. Likewise, Christie spent time with the company after her TV breakthrough. While she learnt much, things didn't always go according to plan. During a production of Live Like Pigs, for example, she got muddled and walked on during the wrong scene and had to lie on the floor pretending to be a rug.

Returning to television, Christie's Judith Northwade crashed into the car of Simon Templar (Roger Moore) in the hope of persuading him to get her father out of a financial jam in 'Judith', a 1963 episode of The Saint (1962-69). The same year saw her play Betty Whitehead in 'Dangerous Corner', an adaptation of J.B. Priestley's acclaimed play for the ITV Play of the Weekv series.

By the time this aired, however, Christie had made her first two films, with director Ken Annakin. In Crooks Anonymous (1962), she was cast as Babette LaVern, a stripper who insists that career criminal Dandy Fosdyke (Leslie Phillips) goes straight before they get hitched. Stanley Baxter took a supporting role as the assistant to crook curer Wilfrid Hyde-White. But, in Christie's sophomore picture, he landed the lead of Murdoch Troon, the cyclist who falls for Claire Chingford (Christie), the daughter of a sports car salesman (James Robertson Justice) in The Fast Lady (1963), which co-starred Phillips as the shifty Freddie Fox.

Christie was less than enamoured with either feature, although they did much to raise her profile. She might have been better known still had she been chosen to play Honey Ryder in the first James Bond film, Terence Young's Dr No. But producer Albert R. Broccoli reportedly passed over her in favour of Ursula Andress because he was more impressed with the Swiss's vital statistics. By contrast, Michael Winner was desperate to cast Christie in West 11 (1963) and was frustrated when his producer insisted on hiring Kathleen Breck instead.

Having not been impressed by her Anne Frank, director John Schlesinger also turned Christie down for the role of typist Ingrid Rothwell in his adaptation of Stan Barstow's A Kind of Loving (both 1962) because he considered her 'too exciting'. The part went to June Ritchie. But Schlesinger had noted Christie when he had encountered her at the Central School of Drama while making a documentary for the BBC's Monitor programme. So, when illness forced Topsy Jane to drop out of his adaptation of Keith Waterhouse's Billy Liar (1963), Schlesinger cast Christie as Liz and amended her character to suit her modish looks and attitude.

He also changed her entrance from meeting Billy (Tom Courtenay) in the classical music section of a department store (as in the book) to a jazz montage of her oozing chic as she sashays symbolically around a part of town that is being redeveloped. Such is Christie's insouciance and the slickness of the shooting and cutting that the episode looks like a commercial or the opening credits for a sitcom (which Billy Liar would become in 1973). It also benefits from Schlesinger's background in actuality, as he was filming from a distance in order to locate Liz within her environment and to capture the genuine reactions of the passers-by to such a flitty free spirit passing among them.

None of them yet had a clue who Christie was, however, and the same was true of the majority of showbiz movers and shakers. So, despite having received £1000 for just two weeks' work, she had to audition for the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, where she appeared in The Country Wife, Thark, The Good Woman of Szechwan, and Next Time I Sing to You. A review in the local paper suggested that those who had heard Christie's song solo in the Christmas revue would be willing to pay to keep her from singing in the future. But the scout from the Royal Shakespeare Company clearly didn't catch her performance and she was cast as Luciana in The Comedy of Errors, which toured major cities behind the Iron Curtain and across the United States in 1964 to mark the 400th anniversary of the birth of William Shakespeare.

On her return, Christie discovered that her 11 minutes on screen in Billy Liar had made her a star. Not only did she earn a BAFTA nomination for her work, but she also received the Variety Club's Most Promising Newcomer Award. Moreover, she landed a five-year contract with producer Joseph Janni. She would later come to regret the move, as she disliked having decisions made for her and felt trapped in a system that was predicated to taking advantage of her. Yet, while she lost out to Millicent Martin for part in Clive Donner's Nothing But the Best, Janni got her the chance to work with the legendary John Ford, who was assisting Jack Cardiff in directing Young Cassidy, a biopic of Irish playwright Seán O'Casey that starred Rod Taylor and cast Christie as the fictional Daisy Battles. Moreover, the association with Janni led to another collaboration with John Schlesinger, much to the frustration of Michael Winner, who had hoped Christie would join Oliver Reed in The System (all 1964).

Lassie the Wonder Dog

Anglo-Amalgamated had wanted Shirley MacLaine to play Diana Scott in Darling (1965). But Schlesinger felt that Christie epitomised the spirit of Swinging London that had emerged on the back of Beatlemania. As the model who comes to prominence during her relationships with television broadcaster Robert Gold (Dirk Bogarde) and publicist Miles Brand (Laurence Harvey), Christie's bright young thing caught the imagination of audiences on both sides of the Atlantic, with her gift for improvisation and the chic Mary Quant-like clothes designed for her by Julie Harris. Like Diana, Christie was soon adorning magazine covers, while her Best Actress triumphs at both the Oscars and the BAFTAs reinforced the impression of Chelsea Girl modernity.

Rather than playing another hipster, however, Christie found herself cast as Lara Antipova in David Lean's epic take on Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago (1965). Omar Sharif took the role of the married medic in revolutionary Russia, while Rod Steiger (Victor Komarovsky), Alec Guinness (Yevgraf Zhivago), and Tom Courtenay (Pavel Antipov) played the men shaping Lara's destiny. With Maurice Jarre's 'Lara's Theme' becoming an international hit, the film was dubbed into 22 languages, which was a record for an MGM picture. Moreover, its inflation-adjusted takings make it the eighth biggest hit in box-office history.

Yet Christie hated every second of the nine-month shoot in Madrid. She resented Lean's dictatorial attitude towards scheduling and his indifference on the set, where the script had to be followed to the last letter. Feeling insecure amongst a predominantly male crew, Christie felt more like a commodity than an actress. But, most of all, she was appalled by 'all the money, the cost and the grandiosity of it all' and she vowed never to repeat the experience. Life magazine declared that 1965 was 'The Year of Julie Christie'. But she found fame hard to accept and was frustrated by the way in which she was presented in the press as a role model modern miss. Despising the way she had to do what she was told, she dubbed herself, 'Lassie the Wonder Dog'.

As a huge fan of the nouvelle vague during her student days, Christie had longed to work with a French new wave director. She was thrilled, therefore, when François Truffaut cast her in the dual roles of Linda Montag and Clarisse in his English-language debut, Fahrenheit 451 (1966), which had been adapted from a dystopia sci-fi classic about book burning and the suppression of ideas and expression by Ray Bradbury. Originally Truffaut had hoped to cast Jean Seberg or Jane Fonda as Clarisse, but he decided to ask Christie to play the character because she was Linda's flipside. However, once again, the shoot proved a disappointment, as Christie struggled to establish a rapport with co-star Oskar Werner, who was busy feuding with Truffaut, who had directed him in Jules et Jim (1961). Perhaps he was aware that he had not been first choice for the role of the fireman whose conscience pricks him, as the producers had rejected Charles Aznavour and Jean-Paul Belmondo for being too niche, while Paul Newman, Peter O'Toole, and Montgomery Clift had been sought before Terence Stamp signed up. But he, who had been dating Christie, dropped out when she doubled up as he didn't want to be overshadowed.

Still under contract to Joseph Janni, Christie did get to work with Stamp, when he was cast as Sergeant Frank Troy opposite her Bathsheba Everdene in Schlesinger's adaptation of Thomas Hardy's Far From the Madding Crowd (1967). Alan Bates and Peter Finch co-starred as shepherd Gabriel Oak and farmer William Boldwood. As before, Christie felt trapped in a paternalistic production, although it did lead to her befriending cinematograper Nicolas Roeg, who would offer her a key role when she was trying to reshape her image in the early 1970s.

Meanwhile, with shutterbugs like David Bailey and Richard Avedon styling her as the epitome of youthful independence and female emancipation, Christie remained the poster girl for the new woman. Time magazine averred, 'What Julie Christie wears has more real impact on fashion than all the clothes of the ten Best-Dressed women combined.' No wonder Peter Whitehead included her in the 'Movie Stars' section of Tonite Let's All Make Love in London (1967).

As scholar Melanie Bell puts it in her excellent tome in the BFI's Film Stars series, 'Christie represented a new version of womanhood: modern, youthful, and independent, an icon of social and sexual liberation.' She appeared to be assembling a peerless CV, as she worked with old masters like Ford and Lean and new wavers like Schlesinger and Truffaut. But, even as she got to collaborate with those maverick exiles, Richard Lester and Joseph Losey, she was unhappy with the way things were going. 'Even in the Sixties, especially then,' she later reflected, 'I was always deeply anxious. I never felt that I was cool enough, or that I was dressed right. Silly things. I was fearful. I did all the things you do, it wasn't that I didn't try lots of things. But I could never quite get away from this anxiety all the time.'

Keen to escape the pressure of being the star responsible for ensuring a mainstream studio picture was a commercial success, Christie started looking for alternative projects that would satisfy her artistic instincts and enable her to highlight the social evils and injustices of which she was becoming increasingly aware. In Richard Lester's Petulia (1968), she played Petulia Danner, the trophy wife of an abusive architect husband (Richard Chamberlain) who has an affair with a married doctor (George C. Scott). She followed this take on John Haase's novel, Me and the Arch Kook Petulia, with Peter Wood's In Search of Gregory (1969), in which the Rome-based daughter of a Swiss financier, Catherine Morelli, becomes obsessed with Gregory Mulvey, a guest from San Francisco who fails to show at her father's wedding in Geneva.

Now best known as the film that created the scheduling problem that forced Michael Sarrazin to pass the Oscar-winning role of Joe Buck in John Schlesinger's Midnight Cowboy (1969) to Jon Voight, this Pinteresque saga was very much a product of its time. It would be Christie's last picture for two years, during which time, she discarded her It Girl persona. As she said later, 'I have no connection with that person at all. That person has gone.' Her replacement would emerge from the political education she received during a lengthy romance with Hollywood's most eligible bachelor.

Difficult Choices

Joseph Losey had tried to persuade Christie to star in his interpretation of William Faulkner's Wild Palms in 1966. However, the terms of her contract made it impossible to do a deal. This was just one of the pictures to which Christie was linked during this period, including Charles Jarrott's Anne of the Thousand Days, Sydney Pollack's They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (both 1969), and Franklin J. Schaffner's Nicholas and Alexandra (1971), which respectively earned Oscar nominations for Geneviève Bujold, Jane Fonda and Susannah York, and Janet Suzman.

She finally came to an arrangement with Losey over L.P. Hartley's The Go-Between (1971), which both Anthony Asquith and Alexander Korda had sought to make before Harold Pinter produced his impeccable screenplay. Losey considered Christie too old at 30 to play the 18 year-old Marian Maudsley and there was little communication between them on the set. Dirk Bogarde, who had starred in his previous Pinter outings, The Servant (1963) and Accident (1967), enjoyed the fact that Losey was not an actor's director, as it left him free to go his own way. But Christie liked to discuss ways of defining and developing her characters, even though she disliked lengthy rehearsals and preferred to work quickly once the cameras started rolling.

With newcomer Dominic Guard playing the 12 year-old guest at Brandham Hall delivering billets doux between Maud and tenant farmer Ted Burgess (Alan Bates), the film won the Grand Prix at Cannes and earned 11 BAFTA nominations, including one for Best Actress. But, while it was shot in Norfolk, Christie was now based in Los Angeles ('I was there because of a lot of American boyfriends'), although she had no intention of returning to the Hollywood scene.

Instead, she joined Warren Beatty in Robert Altman's McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971), a revisionist Western that centres around the bordello in Presbyterian Church, Washington that is owned by gambler John McCabe and prostitute Constance Miller. In addition to discovering a new, collaborative way of film-making with Altman, Christie also learned a good deal about the issues that concerned Beatty ('He gave me a political perspective, which I am very grateful for') and became as much an activist as an actress.

Having earned a second Oscar nomination for Best Actress, Christie returned to Britain to make Don't Look Now (1973) with Nicolas Roeg. Adapted from a short story by Daphne Du Maurier, the action followed grieving parents John and Laura Baxter (Donald Sutherland and Christie), as he goes to Venice to work on the restoration of a church after the accidental drowning of their young daughter. Although the narrative focussed on the effects of bereavement, the press were principally interested in rumours that the stars hadn't merely been acting during a sex scene. But Christie had been more frustrated by Roeg's refusal to contemplate any of her ideas during the shoot and, even though she was nominated for a BAFTA, she regarded this as the last straw when it came to surrendering control when acting.

'I'd let directors tell me what to do,' she later admitted in explaining her decision to change her way of working, 'and I was extraordinarily happy to do so because I didn't think I could accomplish anything myself.' But now, Christie was sufficiently politicised and sure of what she wanted to achieve that she was ready to work on her own terms. As a result, she returned to the stage in 1973 to play Yelena Andreyevna in Mike Nichols's Broadway production of Anton Chekhov's Uncle Vanya, which graced the Chichester Festival before going on tour to Bath, Oxford, Richmond, and Guildford.

She also returned to California to cameo as herself in Robert Altman's country music classic, Nashville. Even though she had parted company with Beatty, she teamed with him again in Hal Ashby's Shampoo (both 1975), a political satire that sees hairdresser George Roundy (Beatty) flirt with Beverly Hills clients Jackie Shawn (Christie), Felicia Karpf (the Oscar-winning Lee Grant), and Jill Haynes (Goldie Hawn). Christie would hook up with Beatty again on Heaven Can Wait (1978), a remake of Alexander Hall's Here Comes Mr Jordan (1941) that sends American football star Joe Pendleton (Beatty) back to Earth in a different body after a celestial snafu. However, wealthy industrialist Leo Farnsworth has just survived a murder attempt by his gold-digging wife, Julia (Dyan Cannon), and her scheming secretary, Tony Abbott (Charles Grodin) and he needs to find a way of surviving their machinations while romancing environmentalist Betty Logan (Christie).

Although Beatty offered her the role of Louise Bryant in Reds (1981), Christie turned it down, even though she had visited Moscow with him in 1969. Beatty's then-partner, Diane Keaton, stepped into the breach, although the film was dedicated to 'Jules' and Beatty referenced Christie during his Best Director acceptance speech at the Academy Awards.

Things were not quite so cordial on the set of Donald Cammell's Demon Seed (1977), a reworking of a Dean Koontz novel about Proteus, a super-intelligent computer that reacts against the efforts of creator Dr Alex Harris (Fritz Weaver) to impose controls by impregnating his child psychologist wife, Susan, who is mourning the loss of her daughter. Given that Cammell and Nicolas Roeg had co-directed Performance (1970), it shouldn't be entirely surprising that they should each cast Christie as a traumatised mother. But this sci-fi curio is markedly less assured than Roeg's gothic chiller, although MGM did take the picture off the director and re-edit it. For Christie, who was annoyed by reviews that critiqued her acting in terms of her manufactured screen image/persona, this was the straw that broke the camel's back as far as Hollywood was concerned and she returned to Britain to take charge of her own life and career.

Redefining Stardom

After 15 years of playing a film star, Julie Christie changed roles. 'My relationship with film directors was paternalistic,' she later explained, 'completely irresponsible in the way I put myself in their hands. That's changed. I'm no longer the little girl letting Daddy do all the work.' Proclaiming her admiration for the way in which director Chantal Akerman and actresses Natalie Baye and Hanna Schygulla approached the representation of women on screen, Christie started seeking projects that reflected her social and political concerns.

Among the first was Victor Schonfeld and Myriam Alaux's The Animals Film (1980), a hard-hitting documentary about vivisection and battery farming that the vegetarian Christie narrated. The tabloid press promptly dubbed her 'Battling Julie' and mocked her along with other activist performers like Jane Fonda, Vanessa Redgrave, and Brigitte Bardot.

Shunning the limelight, Christie moved into a farmhouse near Montgomery in Powys. She explained her alternative lifestyle to a Guardian journalist: ''I have always lived in group situations that are not quite communal. I think it is important to cook on your own, for example, but I have always shared the place with friends. People who have come and gone and had children and so on. I have a family with three children there at the moment. You have to have that in the country, you have to share responsibility for animals and houses and kids.'

Her situation sounded like a scene out of David Gladwell's Memoirs of a Survivor (1981), an adaptation of Doris Lessing's acclaimed treatise on enduring societal collapse. Christie plays D, who hunkers down in her flat as chaos reigns on the streets. However, her magic realist visions of the Victorian past (in which Nigel Hawthorne plays a strict father) take on a new immediacy after she is ordered to share her lodgings with Emily (Leonie Mellinger), a teenager who becomes involved with a refuge for abandoned children.

Allegorising Thatcherite Britain, this sombre saga drew more comments about Christie's deglamorised appearance than its apocalyptic content. But she was barely seen by British audiences as Catherine, the anxious wife of sailor Julien Dantec (Jacques Perrin) in Christian de Chalonge's The Roaring Forties (1982), which drew on the experiences of Donald Crowhurst that would later inspire James Marsh's The Mercy and Simon Rumley's Crowhurst (both 2017).

There was more enthusiasm for her performance as the haughty Kitty Baldry in Alan Bridges's adaptation of Rebecca West's The Return of the Soldier (1982). Alan Bates co-starred as her shell-shocked husband, alongside Ann-Margret as Kitty's concerned sister and Glenda Jackson as Margaret, the childhood sweetheart to whom the confused captain clings. The production proved trying, however, as the money ran out partway through and the cast and crew had to work for nothing to complete the shoot.

Exactly the same situation occurred on Heat and Dust (1983), Ismail Merchant and James Ivory's adaptation of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Booker Prize-winning novel. Returning to India for the first time since her childhood, Christie played Anne, who has travelled to research the life of her Great-Aunt Olivia (Greta Scacchi), a 1920s Raj wife who had caused a scandal by having an affair with the local nawab (Shashi Kapoor). An already deeply personal journey became even more poignant when Christie's mother died while she was on location. But she took great pride in a picture that earned eight BAFTA nominations, with Jhabvala winning for Best Adapted Screenplay.

The same year saw Christie return to the small screen for the first time in two decades. In February 1983, she joined forces with Julie Walters for 'Why Their News Is Bad News', an exposé of media bias sponsored by the Campaign For Press and Broadcasting Freedom that aired as part of the BBC's Open Door (1973-83) programme. At the end of the year she reunited with John Schlesinger to play Mrs Betty Shankland and Miss Railton-Bell in the two vignettes that playwright Terence Rattigan had combined to form Separate Tables. She was joined in this HTV/HBO co-production by Alan Bates, Claire Bloom, and Irene Worth.

Regrettably, this isn't currently available on disc. But Cinema Paradiso users can access Christie's final 1983 outing, Sally Potter's The Gold Diggers, a dissertation on money and female stardom that sees Ruby (Christie) and Celeste (Colette Lafont) delve into the realms of silent cinema and banking. Made by an all-female cast and crew who all received the same payment, this was a bold statement on both an industrial and a creative level. It even took a pot shot at Doctor Zhivago. Potter's debut sought to counter 'sex objectivism' in cinema by subverting the male gaze. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the press pack wasn't entirely sympathetic. But, with its dance numbers and reveries, the feature has rightly come to be seen as a feminist landmark.

This highly significant project reflected Christie's new approach to an industry in which she was 'surrounded by all the things you hate most in life, which are consumerism and advertising and celebrity and false representation'. Consequently, she turned down Curtis Harrington's invitation to play the lead in what she considered to be his misogynist adaptation of Iris Murdoch's The Unicorn (1963), as the character Marian Taylor was 'a passive woman dominated by men'. Similarly, she declined a role in Joseph Losey's take on Nell Dunn's Steaming (1985) because she felt its nudity would be exploitative. In a letter to the American, she wrote: 'I loathe having to turn down the opportunity to work with a good director...and I probably won't get another chance to do something as interesting...for years, but there we are. [...] I hope you won't hold this against me. People sometimes do.'

The part went to Sarah Miles, but Christie was keeping herself busy. In 1986 alone, she appeared in three features, a mini-series, and a short. The latter, Ave Maria, was directed by the great Hungarian auteur, Márta Mészáros, while Bernhard Sinkel's Sins of the Fathers cast Christie as Charlotte Deutz in four episodes following the fortunes of a German and a Jewish family in the 1920s and 30s. Wealth and influence was also the theme of Sidney Lumet's Power. which saw Christie play Ellen Freeman, the ex-wife of Richard Gere's ruthless, but suddenly conscience-stricken media analyst, Pete St John.

Christie next travelled to Tunisia for Ridha Behi's Champagne amer (aka Secret Obsession), in which she played Betty, a nightclub singer who bewitches both landowner Paul Rivière (Ben Gazzara) and his illegitimate son, Wanis (Patrick Bruel). Rounding off the year, she went to Argentina to essay Mary Mulligan in Maria Luisa Bemberg's Miss Mary (all 1986), an examination of the British colonial legacy that opens in 1938 and centres on an English governess caring over seven years for the three children of an affluent couple in a Buenos Aires shaken by the rise of Juan Perón.

Having narrated a pair of documentaries, Agent Orange: Policy of Poison and Yilmaz Guney: His Life, His Films (both 1987), Christie became an Oxfam Ambassador and went to Cambodia to make two shorts about the situation in Kampuchea, Miracle Under Threat (1988) and Caught in the Cross Fire (1989). Continuing to select projects that chimed in with her activist causes, she played Barbara Barlow, the mother of a man awaiting execution in Malaysia for drug trafficking in Jerry London's teleplay, Dadah Is Death (1988).

Returning to the big screen, Christie played Ellie Quinton in Pat O'Connor's take on William Trevor's Fools of Fortune (1990), which sees a wealthy Protestant family become embroiled in the war against the British when scion Willie (Iain Glen) falls for outsider, Marianne (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio). Staying in Ireland, she reunited with Donald Sutherland to play Helen Cuffe, a widow whose friendship with an American artist is regarded as a political betrayal in Michael Whyte's The Railway Station Man (1992).

During a sabbatical, Christie took an Open University course in Eastern religions. But her seizing control of her life didn't go down well in certain quarters of the press, where she was criticised for turning her back on fame and for pursuing esoteric projects that interested her more than the cinema-going public. As she confided to the Guardian, 'people are cross somehow, underneath, that I am not the person that I was. They feel like I am letting them down in some way. I sometimes feel they dislike me for appearing with all my lines and wrinkles. As a culture we seem unable to embrace change in people without being harsh about it.'

She looked back on the first phase of her career in series like Hollywood U.K. (1993) and such documentaries as François Truffaut: The Man Who Loved Cinema - Love & Death (1996). But she also continued to explore human interest issues by narrating the actuality, Katie and Eilish: Siamese Twins (1992). She even ventured back on to the stage for Old Times at the Royal Court Theatre in 1995 and Suzanna Andler at Wyndham's Theatre two years later.

On television, she was Lady Ruth Balmer in the 'Wednesday' and 'Friday' episodes of Renny Rye's BBC version of Dennis Potter's Karaoke. But her highest-profile outing for quite some time came when Kenneth Branagh persuaded her to play Gertrude, the Danish prince's hastily remarried mother, in his epic adaptation of Hamlet (both 1996).

Into That Good Night

Christie once joked, 'I think I work, I actually work, every ten years.' She does have little spurts of activity in the public eye, but she's not the type to wallow in luxury. Indeed, she claimed after one busy period that she had only accepted so many parts because her roof needed repairing.

After six years away from the cinema, Christie was coaxed into playing Queen Aislinn in Rob Cohen's fantasy adventure, Dragonheart (1996), which was her first Hollywood film in years. She played the Irish mother of the Saxon prince, Einon (David Thewlis), who is trained by the knightly Sir Bowen (Dennis Quaid) to defeat a dragon named Draco (who is voiced by Sean Connery). The papers, however, were more interested in the fact that Christie had undergone cosmetic surgery to remove what she called 'all those double chins'.

Considerations of mortality impacted upon her character in Alan Rudolph's Afterglow (1997), which sees faded film actress Phyllis Hart drifts into an affair with younger business executive Jeffrey Byron (Jonny Lee Miller) just as her builder husband, Lucky Mann (Nick Nolte), falls for Jeffrey's broody wife, Marianne (Lara Flynn Boyle). Christie received an Oscar nomination for her work in the Robert Altman-produced dramedy, which really should be available on disc.

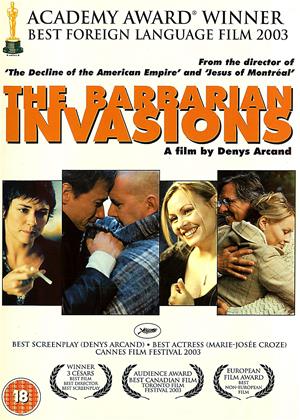

The same year saw Christie gifted a BAFTA Fellowship for lifetime achievement and she remained in a cine-frame of mind through her contributions to the documentaries Joseph Losey: The Man With Four Names (1998), La Fabrique aux acteurs (2001), A Decade Under the Influence (2003), Cycle of Peace, and Garbo (both 2005), which she narrated. She also voiced Rachael in the New Testament animation, The Miracle Maker (1999), and cropped up in two episodes of the mini-series, Starstruck (2000). But few got to see her feature turns as Glenda Spender in Jean-Paul Salomé's Belphegor, Phantom of the Louvre, Dr Anna in Hal Hartley's No Such Thing (both 2001), Dori in Jon Sherman's I'm With Lucy, or as Narma in Rudolf van den Berg's Snapshots (both 2002), in which she co-starred with Burt Reynolds. You also had to be quick to spot her playing herself in Denys Arcand's The Barbarian Invasions (2003).

Far higher profile were her cameos as Thetis, the mother of Achilles (Brad Pitt), in Wolfgang Petersen's Troy, and as Madam Rosmerta in Alfonso Cuarón's Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Having joined Marianne Faithfull in Bruce Weber's delightful doggy documentary, A Letter to True, Christie concluded a busy 2004 by earning a BAFTA nomination for her performance as Emma du Maurier, the mother of Sylvia Llewelyn Davies (Kate Winslet), in Marc Forster's Finding Neverland, which starred Johnny Depp as Peter Pan author, J.M. Barrie.

Suddenly back in the spotlight, Christie found herself returning to the Academy Awards after she was nominated for Best Actress for playing Fiona Anderson, a Canadian woman living with Alzheimer's who breaks the heart of her husband (Gordon Pinsent) when she forgets him and falls instead for a resident of her care home (Michael Murphy) in Sarah Polley's Away From Her (2007). Polley had read Alice Munro's short story, 'The Bear Came Over the Mountain', while flying home from Iceland, where she had been shooting Isabel Coixet's The Secret Life of Words (2005), in which Christie had played a Danish trauma specialist named Inge. She knew she had to take the lead in her directorial debut and spent months trying to persuade her to take the role.

Eventually, Christie relented 'because Sarah is this extraordinary talent, and I did not want anyone else to have the experience of working with her on her first movie'. She was rewarded with a BAFTA nomination, a Golden Globe, and a Screen Actor's Guild Award, as well as some of the best reviews of her entire career. True to form, however, she attended the Oscars wearing a badge demanding the closure of the prison at Guantanamo Bay.

Making a last return to the stage to appear in Cries From the Heart at the Royal Court in 2007, Christie narrated the Survival International short, Uncontacted Tribes. She also teamed with Shia LaBeouf in the New York, I Love You (also 2008) segment that had been written by Anthony Minghella and directed by Shekhar Kapur. The following year, she graced Steven Poliakoff's Glorious 39 (2009), as the haughty Aunt Elizabeth making acerbic remarks about the state of the nation on the eve of the Second World War.

Having vamped up the role of the grandmother in Catherine Hardwicke's Red Riding Hood (2011), Christie gave her last performance to date as Mimi Lurie, a former member of the militant Weather Underground group, in Robert Redford's The Company You Keep (2012). She has since narrated The Afectados (2015), a short on an American oil company's contamination of the Ecuadorian Amazon, and Cinema Paradiso users can also hear her narrating Isabel Coixet's charming drama, The Bookshop (2017), which stars Emily Mortimer, Patricia Clarkson, and Bill Nighy. She featured in Briar March's tribute to the Greenham Common women, Mothers of the Revolution (2021), and has been linked with Dragana Latinovic's documentary, Midnight Men - A John Schlesinger & Michael Childers Story, which is still in production. It remains to be seen, however, whether Christie can be lured away from journalist husband Duncan Campbell and back in front of the camera. But, as she turns 85, she has left us with a lifetime of memorable roles and resolutions made and kept for the boldest and bravest of reasons.