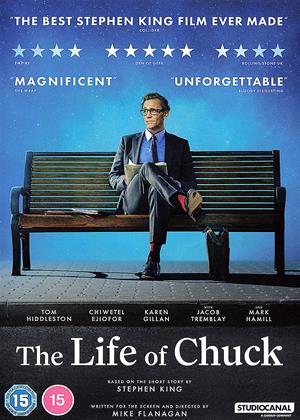

Rent The Life of Chuck (2024)

- General info

- Available formats

- Synopsis:

- Based on Stephen King's novella and brought to the screen by acclaimed director Mike Flanagan (Doctor Sleep), 'The Life of Chuck' is the tale of a seemingly unremarkable man called Charles Kranz (Tom Hiddleston). Told in reverse order, Chuck's life story unfolds over three chapters, reminding us that even the most ordinary life contains multitudes.

- Actors:

- Tom Hiddleston, Jacob Tremblay, Benjamin Pajak, Cody Flanagan, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Karen Gillan, Mia Sara, Carl Lumbly, Mark Hamill, David Dastmalchian, Harvey Guillen, Michael Trucco, Q'Orianka Kilcher, Matthew Lillard, Rahul Kohli, Violet McGraw, Saidah Arrika Ekulona, The Pocket Queen, Annalise Basso, Andrew Grush

- Directors:

- Mike Flanagan

- Producers:

- Mike Flanagan, Trevor Macy

- Voiced By:

- Nick Offerman, Carla Gugino, Elan Gale, Eric Vespe, Scott Wampler, Hamish Linklater, Axelle Carolyn, Sandra Hess, Alexa Bolter, Lauren LaVera, Mikki Levi, Raymond Garcia

- Narrated By:

- Nick Offerman

- Writers:

- Mike Flanagan, Stephen King

- Aka:

- La vida de Chuck

- Studio:

- StudioCanal

- Genres:

- Drama, Sci-Fi & Fantasy

- BBFC:

- Release Date:

- 10/11/2025

- Run Time:

- 111 minutes

- Languages:

- English Audio Description, English DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1

- Subtitles:

- English Audio Description, English Hard of Hearing

- Formats:

- Pal

- Aspect Ratio:

- Widescreen 1.85:1

- Colour:

- Colour

- BLU-RAY Regions:

- B

- Bonus:

- On-set interviews with Chiwetel Ejiofor, Mark Hamill, and Tom Hiddleston

- The Making of 'The Life of Chuck'

- BBFC:

- Release Date:

- 10/11/2025

- Run Time:

- 111 minutes

- Languages:

- English Audio Description, English DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1

- Subtitles:

- English Hard of Hearing

- DVD Regions:

- Region 0 (All)

- Formats:

- Pal

- Aspect Ratio:

- Widescreen 1.85:1

- Colour:

- Colour

- BLU-RAY Regions:

- (0) All

- Bonus:

- On-set interviews with Chiwetel Ejiofor, Mark Hamill, and Tom Hiddleston

- The Making of 'The Life of Chuck'

- Feature Commentary with Writer/Director Mike Flanagan

More like The Life of Chuck

Found in these customers lists

Reviews (2) of The Life of Chuck

Life’s a Rewind… Until the Tape Runs Out - The Life of Chuck review by griggs

Life doesn’t usually come with a rewind button, but here it does—and under Mike Flanagan’s assured direction, the effect is oddly exhilarating. We start at the end, with the world folding in on itself, before moving backwards through moments of street-dancing abandon and into the wide-eyed promise of childhood. It’s a story about horizons: how they narrow with age, then widen again as memory unspools in reverse.

Flanagan steers this tricky structure with a light but deliberate touch, balancing warmth and melancholy without tipping into sentimentality. The apocalyptic opening plays like the shutting-down of a private universe, each scene selling off another fragment of the life lived within. The middle act, brimming with defiance in the face of decline, has a spontaneity that feels both joyous and fragile.

By the time we reach the beginning, the reverse journey feels less like an ending than a sly reminder: life’s possibilities—real or imagined—are as vast as we allow them to be, until they aren’t. Flanagan turns what could have been a gimmick into a poignant meditation on mortality, perspective, and the strange comfort of seeing it all in reverse.

Starts well, goes nowhere - The Life of Chuck review by Alphaville

A film of 3 acts, each one set earlier in time. The first act is an interesting fantasy set at the end of the world as we know it (there are even exploding planets). It’s not overly woke and it does make you want to know more. Unfortunately there will be no explanation and there’s barely any connection with acts 2 and 3, which follow the day-to-day life of a different character (the eponymous Chuck). Even worse, act 2 is mainly an overlong street dance, and act 3 also has a lot of pointless dancing in it. Probably more interesting is the set of Extras, where the cast make failed attempts to explain what it’s all about. Something to do with isn’t life wonderful etc. Still, it’s well made and keeps you watching, even if it’s ultimately pointless. They should have stuck with act 1 and followed it through.