Let's take a look back at how cinema and television have depicted the office of prime minister and the historical and fictional holders of the office.

Although politics play an intrinsic part in almost every aspect of daily life in the United Kingdom, the makers of films and television programmes have often been reluctant to depict their workings on screen. The power of cinema to shape public opinion had been realised during the Great War and the authorities were keen to prevent film-makers from imposing their views on the public. Consequently, with political feelings running high between the 1926 General Strike and the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the British Board of Film Censors was encouraged to reject pictures seeking to promote ideologies that might tilt the balance of power. This didn't simply mean outlawing films from Communist Russia or Nazi Germany, however. Anything that could sway voters was frowned upon, hence BBFC president Lord Tyrrell being able to boast in 1937: 'We may take pride in the fact that there is not a single film showing in London which deals with any of the burning issues of the day.'

The First Stirrings

Although newsreels presented a sanitised version of the Great Depression and the British Documentary Movement occasionally examined the harsher side of life, the social and political issues facing the country during the 1930s were very much relegated to the background, if they were addressed at all. Based on bestsellers by Winifred Holtby and AJ Cronin, Victor Saville's South Riding, King Vidor's The Citadel (both 1938) and Carol Reed's The Stars Look Down (1939) paved the way for what would become known as 'the problem picture' in the immediate postwar period. But the BBFC tried to ban John Baxter's adaptation of Walter Greenwood's controversial working-class novel, Love on the Dole (1941), as it emphasised division at a time when national unity was key, and it was something of a surprise that the censor passed Basil Dearden's They Came to a City (1944), as JB Priestley's scenario depicted a postwar socialist idyll that welcomed people from all walks of life.

Anticipating the Labour landslide celebrated in Ken Loach's documentary, The Spirit of '45 (2013), this earnest fantasy was hailed by the left-leaning Daily Worker as 'one of the most enterprising efforts ever made in the British cinema'. Dramas like John Harlow's The Agitator (1945) similarly strove to reassure audiences that socialist rule didn't mean radical upheaval. although Michael Balcon's Ealing Studios frequently poked fun at the government in deceptively sharp comedies like Henry Cornelius's Passport to Pimlico (1949) and Alexander Mackendrick's The Ladykillers (1955), which was widely viewed as a satirical swipe at Prime Minister Clement Attlee and his cabinet.

While postwar cinema became increasingly open to exploring socio-political themes, they were rarely discussed in television drama. Indeed, both the BBC and ITV agreed not to show films with political undertones around election time in case they influenced voters. Even mild comedies like Oswald Mitchell's Old Mother Riley, MP (1939) were deemed potentially inflammatory, let alone outings like the Boulting brothers duo, Fame Is the Spur (1947), which novelist Howard Spring had loosely based on the life of former Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald, and I'm All Right Jack (1959), a satire on trade unionism that had opened in cinemas around the time of the 1959 General Election.

The same year saw the release of Sidney Gilliat's Left Right and Centre, in which the ennobled Alastair Sim seeks to secure a safe seat for nephew Ian Carmichael at a by-election. Two years later, Ralph Thomas lifted the lid on parliamentary life in No Love For Johnnie, an adaptation of a novel by Labour backbencher Wilfred Fienburgh. Peter Finch won the BAFTA for Best Actor for his performance as an MP whose private life becomes public in a manner that anticipated the Profumo Affair that Michael Caton-Jones revisited in Scandal (1989), which starred Ian McKellen as War Minister John Profumo, who had to resign in the wake of the revelation that he had been consorting with showgirls Christine Keeler (Joanne Whalley) and Mandy Rice-Davies (Bridget Fonda). However, with politics now a permissible target for satire on TV shows like That Was the Week That Was (aka TW3; 1962-62) and Till Death Us Do Part (1965-75), cinema was edged out of the debate during the Swinging Sixties, as the lengthy production schedules meant that films about topical events would have been out of date by the time they reached the screen.

Big Screen Premiers

Although film-makers had reflected on the careers of historical figures in the name of patriotism, they remained reluctant to depict fictional prime ministers on the big screen. Once again, it was John and Roy Boulting who took the leap by placing the Honourable Arthur Lytton (Ronald Adam) at the centre of events in Seven Days to Noon (1950), which earned Paul Dehn and James Bernard the Oscar for Best Story. The PM receives a letter from Professor Willingdon (Barry Jones), informing him that he intends to detonate a warhead stolen from a secret research centre in the centre of London unless the government abandons its atomic weapons. Although Scotland Yard's DS Folland (André Morell) leads the hunt for the rogue academic, Lytton has to broadcast to the nation to allay fears of an imminent declaration of war and to appeal to Willingdon to give himself up.

But two decades would pass before a British film would repeat such prime ministerial emphasis, although it proved well worth the wait. Devised and produced by David Frost (the eminence grise behind TW3) under the pseudonym David Paradine, Kevin Billington's The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer (1970) was co-scripted by future Pythons John Cleese and Graham Chapman and its star, Peter Cook, who had been in the vanguard of the satire boom since teaming with Alan Bennett, Jonathan Miller and Dudley Moore in Beyond the Fringe. Terry Johnson recalled this phase of Cook's career in Not Only But Always (2004), with Rhys Ifans and Aidan McArdle as Pete and Dud, who would be mischievously name-checked as Michael Rimmer (Cook) stands for election at Budleigh Moor in order to help Tory leader Tom Hutchinson (Ronald Fraser) oust Labour incumbent Blocket (George A. Cooper) from 10 Downing Street, en route to launching his own bid for dictatorial power.

As Blocket bore a less than subtle similarity to Harold Wilson, the film was held back until after the 1970 General Election, by which time its edge had been blunted. But Cook returned to power as Sir Mortimer Chris in Tom Bussmann's Whoops Apocalypse (1986), which had been spun-off a 1982 ITV series of the same name by writers Andrew Marshall and David Renwick. On the small screen, Labour's Kevin Pork (Peter Jones) had presided over the cabinet while under the impression that he was Superman, but Cook's premier proved even more certifiable, as he blames unemployment on evil pixies and seeks to solve the problem by pushing people with jobs off cliffs. He also takes to crucifying disloyal party members at Wembley Stadium, while trying to reclaim an obscure colony from its bellicose neighbour, Maguadora.

By comparison, it's easy to overlook the anonymous PMs played by Faith Brook in Andrew V. McLaglen's North Sea Hijack (1980), Michael Gambon in Mark Mylod's Ali G Indahouse (2002) and Robbie Coltrane in Geoffrey Sax's Stormbreaker (2006). James Villiers made more of an impression as Jeffrey Hale in David S. Ward's King Ralph (1991), as he warns American working stiff Ralph Jones (John Goodman) against doing anything that will give Lord Percival Graves (John Hurt) a chance to challenge his succession to the throne. Anglo-American relations also preoccupy David (Hugh Grant), the prime minister without a surname in Richard Curtis's Love Actually (2003), who rescues tea-lady Natalie (Martine McCutcheon) from the clutches of the sneering US president (Billy Bob Thornton).

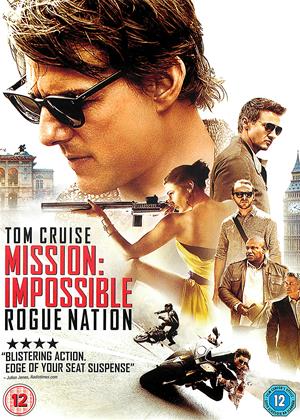

While his oratory might not be particularly inspirational, as he bigs up 'the country of Shakespeare, Churchill, The Beatles, Sean Connery, Harry Potter. David Beckham's right foot. David Beckham's left foot, come to that', David has the common touch. He also has a good deal more screen time than the anonymous leaders played by Kevin McNally in Peter Howitt's Johnny English (2003) and Tom Hollander in Christopher McQuarrie's Mission: Impossible - Rogue Nation (2015), although the latter contributes a scene-stealing exchange during a charity auction at Blenheim Palace (the birthplace of Winston Churchill) with the man he thinks is the drolly named secret service chief, Atlee (Simon McBurney).

A number of PMs have found themselves imperilled in recent movies, including John Hatcher (Alexander Siddig) in Neil Marshall's Doomsday (2008), Leighton Clarkson (Clarkson Guy Williams) in Babak Najafi's London Has Fallen (2016) and the unseen leader in Paul Tanter's He Who Dares and He Who Dares: Downing Street Siege (both 2014), which respectively see SAS Captain Chris Lowe (Tom Benedict Knight) rescue the prime minister's daughter and thwart a kidnap plot at No.10.

It's hard to escape the presence of Adam Sutler (John Hurt) in James McTeigue's V For Vendetta (2006), which was adapted by the Wachowskis from a graphic novel by Alan Moore and David Lloyd. Strictly, the former Conservative MP and Under-Secretary for Defence is installed as High Chancellor when his neo-fascist Norsefire Party takes power in 2032. But there's no time to split hairs in this dystopic saga, which would make for a compelling double bill with Michael Radford's take on George Orwell's 1984 (1984), in which Hurt had played Winston Smith, who seeks to avoid the omnipresent gaze of Big Brother (Bob Flag).

Skeletons also threaten to come tumbling out of the cupboard in Roman Polanski's The Ghost (2010), a twisting thriller derived from the Robert Harris bestseller that was reportedly inspired by Tony Blair's role in Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. Former 007 Pierce Brosnan excels as Adam Lang, who is working on his memoirs with an amanuensis (Ewan McGregor) when he is accused by ex-Foreign Secretary Richard Rycart (Robert Pugh) of sanctioning illegal terrorist exchanges with the United States.

Small Screen PMs

Although Charles Dickens frequently included prime ministers in his novels, they never seemed to make the cut when it came to adapting them for the small screen. However, a couple of Anthony Trollope's First Lords have been retained, which is only fitting, as he actually published an 1876 tome entitled, The Prime Minister. This was the fifth entry in the Parliamentary cycle, which was adapted in 26, hour-long episodes for the BBC by Simon Raven. During the course of The Pallisers (1974), both Joshua Monk (Bryan Pringle) and Plantagenet Palliser, Duke of Omnium (Philip Latham) hold the highest office in the land, although there was no sign of the latter when Stephen Norrington reworked Alan Moore and Kevin McNeill's graphic novel, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003), even though he had featured in Volume 1.

Two more premiers to make the transition from page to screen are Lord Bellinger and David MacAdam. The former was played by Harry Andrews in 'The Adventure of the Second Stain', a 1986 episode of The Return of Sherlock Holmes, in which Holmes (Jeremy Brett) and Watson (Edward Hardwicke) are hired to retrieve a stolen diplomatic dispatch that could lead the country into war. The latter was essayed by Henry Moxton in 'The Kidnapped Prime Minister', a 1990 case for David Suchet in Agatha Christie's Poirot that gave the Belgian sleuth 32 and a quarter hours to find the missing politician before a crucial arms summit.

The entire way in which politics was approached on television changed when writers Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn launched the BBC sitcom, Yes Minister (1980-84). A personal favourite of Margaret Thatcher (who actually made a guest appearance in a specially written sketch), the series centred on Jim Hacker (Paul Eddington), who was dispatched to the Department for Administrative Affairs by Prime Minister Herbert Atwell, where he was served by Permanent Secretary Sir Humphrey Appleby (Nigel Hawthorne) and Principal Private Secretary Bernard Woolley (Derek Fowlds). They accompanied Hacker to Downing Street in Yes, Prime Minister (1986-88), in which he demonstrated just how difficult it is to remain atop what Benjamin Disraeli had called 'the greasy pole'.

Sticking with comedy, having become the MP for the rotten borough of Dunny-in-the-Wold in Blackadder the Third (1987), Baldrick (Tony Robinson) settles in for five terms as the PM of King Edmund III (Rowan Atkinson) in the time-travelling millennial special, Blackadder: Back & Forth (1999). But nobody has discredited high office more scurrilously than Alan B'Stard (Rik Mayall) in Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran's gleefully over-the-top political romp, The New Statesman (1987-94). Having entered the Commons as MP for Haltemprice, B'Stard serves on the backbenches for both Margaret Thatcher (Steve Nallon) and an unseen John Major before becoming an MEP and the leader of the eurosceptic New Patriotic Party. In the fourth series, he prevents Labour's Paddy O'Rourke (Benjamin Whitrow) from becoming PM by staging a coup and declaring himself Lord Protector. However, B'Stard does become prime minister at the end of a 2011 No2AV commercial opposing the alternative vote method of polling.

It's a shame that B'Stard never got to lock horns with Malcolm Tucker (Peter Capaldi), the vicious spin doctor concocted by Armando Iannucci for The Thick of It (2005-12), the BBC series that spawned the 2009 feature, In the Loop, which earned the director and his co-writers an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay In the landmark sitcom, the PM advised by Tucker is never seen. However, in The Specials (2007), we do learn that the supporters of leader-in-waiting Tom Davis are known as 'The Nutters'. Iannucci would go on to demonstrate an equally acute understanding of American politics in Veep (2012-18), which brought Julia Louis-Dreyfus an Emmy, and the Soviet hierarchy in the early 1950s in The Death of Stalin (2017).

Although Anthony Head played PM Michael Stevens as a thoroughly good egg in his dealings with besotted aide Sebastian Love (David Walliams) in Little Britain (2003-06), the Machiavellian nature of politics has increasingly been exposed in TV drama series since the Thatcher era. Among the first to linger on the skullduggery was Granada's 1986 adaptation of Jeffrey Archer's First Among Equals, with Tom Wilkinson as Prime Minister Raymond Gould. But a novel by MP Chris Mullin provided a grittier insider view in Mick Jackson's A Very British Coup (1988), which sees newspaper magnate Sir George Fison (Philip Madoc) forge an alliance with MI5 chief Sir Percy Browne (Alan McNaughton) to prevent new Labour PM Harry Perkins (Ray McAnally) from carrying out an agenda that includes nuclear disarmament, a withdrawal from NATO and the ending of press monopolies.

This simmering series was reworked for Ed Fraiman's Channel 4 offering, State Secret (2012), which sees PM Charles Flyte (Tobias Menzies) perish in a plane crash while returning to Blighty from America after 19 people are killed in an explosion at the PetroFex plant at Scarrow on Teesside. Chief Whip John Hodder (Charles Dance) persuades Deputy Prime Minister Tom Dawkins (Gabriel Byrne) to take the step up, even though the Sheffield MP has doubts about his leadership skills. But, with friends like Home Secretary (and later Chancellor) Felix Durrell (Rupert Graves), he's bound to be okay. Isn't he?

As a former chief of staff at Conservative head office, Michael Dobbs was equally well placed to pen The House of Cards, the novel that was adapted by Andrew Davies for BBC director Paul Seed in 1990. The four-parter followed the fortunes of Chief Whip Francis Urquhart (Ian Richardson) after he decides that Henry Collingridge (David Lyon) is an unworthy successor to Margaret Thatcher. Breaking the fourth wall to take the audience into his confidence, the Oxford-educated MP for New Forest employs various black arts to fix the ensuing leadership contest. In the second part of the trilogy, To Play the King (1993), Urquhart's prime minister locks horns with a new monarch (Michael Kitchen), while in The Final Cut (1995), he comes under pressure from Foreign Secretary Tom Makepeace (Paul Freeman) in his bid to beat Thatcher's record as the UK's longest-serving PM.

Until his fall from grace, Kevin Spacey took the role of Democratic Congressman Frances Underwood in the variation of House of Cards (2013-18). Racking up an unprecedented nine Emmys, The West Wing (1999-2005) will remain for many the acme of American political shows. But the Special Relationship was very much kept on the back burner, as President Josiah Bartlett (Martin Sheen) didn't meet with a British prime minister and it was only in Season Six that successor Matt Santos (Jimmy Smits) bails out PM Maureen Graty (Pamela Salem) after she brings the UK to the brink of war with Iran after the shooting down of a passenger jet.

By contrast, everyone's favourite Time Lord has met more than his share of prime ministers over the years. Among those to have graced Doctor Who (1963-) in recent times are Joseph Green (David Verrey) in 'World War Three', Harriet Jones (Penelope Wilton) in 'The Christmas Invasion' (both 2005) and Harold Saxon (aka The Master; John Simm) in 'The Sound of Drums' and 'Last of the Time Lords' (both 2007). Moreover, Don Warrington was cast as the president of Great Britain in 'Rise of the Cybermen' (2006), while Nicholas Farrell played PM Brian Green in the 2009 'Children of Earth' episode of the spin-off series, Torchwood (2006-11).

The turn of the century saw a bid to present the human side of politics, with 12 year-old Dillon (Joe Prospero) offering a kid's eye-view of the efforts of father Michael Phillips (Robert Bathurst) to run the country in My Dad's the Prime Minister (2003), which was scripted by Nick Newman and Private Eye editor and Have I Got News For You regular, Ian Hislop. However, the BBC found fewer takers for Ros Pritchard (Jane Horrocks) and her Purple Democratic Alliance in The Amazing Mrs Pritchard (2006), while Channel Four found itself anticipating the headlines when Prime Minister Michael Callow (Rory Kinnear) agrees to commit a bestial act with a pig on live television to secure the release of a kidnapped princess in the first episode of Charlie Brooker's bleak satire, Black Mirror (2011-).

Despite starting off on the big screen, David Hare's 'Worricker trilogy' eventually found a home on BBC2. In Page Eight (2011), MI5 officer Johnny Worricker (Bill Nighy) discovers that PM Alec Beasley (Ralph Fiennes) has been hiding intelligence about secret American torture centres and plans to replace the existing spy network with a homeland security operation. While laying low in the Caribbean in Turks and Caicos, Worricker manages to link Beasley to a charitable foundation involved with a sinister US organisation sponsoring covert CIA operations, while the ever-scheming Beasley seeks to protect himself by bugging Worricker's pregnant daughter in the concluding episode, Salting the Battlefield (both 2014).

Having scooped a BAFTA and an Emmy for depicting the Tory Party's efforts to contain a sex scandal in Graham Theakston's The Politician's Wife (1995), writer Paula Milne returned with Simon Cellan-Jones's The Politician's Husband (2013), in which the marriage of political golden couple Aiden Hoynes (David Tennant) and Freya Gardner (Emily Watson) comes under severe strain after Hoynes asks his wife to play a supporting role while he takes a tilt at the top job. The tension is ratcheted up even further in Jon Cassar's 24: Live Another Day (2014), as Jack Bauer (Kiefer Sutherland) finds himself in London as US President James Heller (William Devane) seeks the support of Prime Minister Alastair Davies (Stephen Fry) in some sabre rattling to avert a war with China.

Another crisis looms in Rupert Goold's King Charles III (2017), an adaptation of Mike Bartlett's provocative stage play in which PM Tristan Evans (Adam James) strives to talk the new monarch (Tim Pigott-Smith) to do what's best for the country after waiting a lifetime to rise from being Prince of Wales. And the relationship between Buckingham Palace and Downing Street comes under further scrutiny in The Royals (2015-17), as PM David Edwards (David Broughton-Davies) seeks to referee the in-fighting when Queen Helena (Elizabeth Hurley) vows to oppose the plans of King Simon Henstridge (Vincent Regan) to abolish the monarchy.

Later this year, viewers will get a chance to see Robert Carlyle play Prime Minister Robert Sutherland in Sky One's COBRA, In the meantime, they can relive Jed Mercurio's gripping six-parter, Bodyguard (2018), which sees Afghan War veteran David Budd (Richard Madden) assigned to protect Julia Montague (Keeley Hawes), the ambitious Home Secretary in the Conservative administration of The Rt. Hon. John Vosler (David Westhead). The series brought the BBC its highest audience figures in a decade. So there's bound to be a second season, isn't there?

Interested in more historical and fictional figures from politics? Check out our Political Dramas section and find even more suggestions for your next film night.