An icons of 1960s British cinema who went on to make his mark in Europe, America, and, memorably, in Australia, Terence Stamp has died at the age of 87. Cinema Paradiso pays its respects.

Reading many of the tributes that have been written about Terence Stamp since his death on 17 August, one could be forgiven for believing that the only thing he did in his career after his iconic Swinging Sixties image faded was t play the villain in a superhero movie. Stamp certainly came down to earth with a bump in the 1970s. But he dusted himself down and got on with being a jobbing actor - albeit one of the most stylish and distinctive in the business.

As told The Guardian: 'I don't have any ambitions. I'm always amazed there's another job, I'm always very happy. I've had bad experiences and things that didn't work out; my love for film sometimes diminishes but then it just resurrects itself. I never have to gee myself up, or demand a huge wage to get out of bed in the morning. I've done crap, because sometimes I didn't have the rent. But when I've got the rent, I want to do the best I can.'

These are the words of a man who understood himself and his place in the world. For all the credits and accolades he accrued over six decades in the public eye, that may well be his crowning achievement.

Bow Bells Boy

Terence Henry Stamp was born on 22 July 1938 in Stepney. Father Thomas was a stoker who would spend much of the Second World War with the Merchant Navy before becoming a tugboat skipper on the Thames. Mother Ethel relied on the help of aunts and a grandmother to raise Terence and younger siblings Christopher, Richard, John, and Linette, but she always insisted that they were smartly dressed to distract from the fact that money was tight. Bombed out of Bow during the Blitz, the Stamps settled into a house at the end of a Plaistow terrace that Terence could never remember being visited by non-family members.

Stamp claimed his father was 'emotionally closed down' to anyone but his wife. But he describes a contented childhood in his various volumes of autobiography, despite often having to subsist on potatoes, jam, bread, and tea. 'We were very poor,' he explained, 'but I don't regret it. It makes me so much more appreciative. Also I've got something to fight against. Luxuries will never be a necessity for me. My memory of poverty is too vivid. I'll never take anything for granted.'

He taught himself to read by poring over Ethel's Woman's Own magazines and quickly became a devotee of Rupert the Bear, something he shared with fellow 60s legend, Paul McCartney. His 'Rupert and the Frog Song' (1985) can be rented from Cinema Paradiso as part of Paul McCartney: The Music and Animation Collection (2001). As for Stamp, he was still reading Rupert in his fifties, 'I find it heightens my sense of my own emotions, clarifies things somehow.'

His great passion, however, was the cinema, which he first experienced at the age of three, when Ethel took him to see William A. Wellman's Beau Geste (1939). 'The empathy I felt from Gary Cooper,' Stamp wrote in his 2017 memoir, The Ocean Fell Into the Drop, 'was life-changing, and a secret dream was born in the darkened auditorium.' Another youthful hero was Errol Flynn, although the teenage Terence was in thrall to Marlon Brando and James Dean. By this time, he had acquired the family nickname of 'Lord Fauntleroy' because he was so particular about his appearance. Moreover, he had developed an ambition to become an actor.

'I saw my first movie, and I just wanted to be that,' he later wrote. 'And I never really spoke about it. In other words, it was a very private sort of fantasy that I had. And when it got to sort of near leaving school, in other words, let's say I was like 15, 16 and we got our first television, I started making remarks about, oh, I could do that; oh, I could do better than that. And my dad, he sort of wore that for a bit. And then one evening, I was carrying on about how good I thought I could be in that part, and he said to me, listen, son. People like us don't do things like that. And I went to sort of protest. And he said son, I just don't want you to talk about it anymore.'

Having passed the 11+ examination, Stamp attended Plaistow County Grammar School. But he hated learning by rote and left without passing any of his eight GCSE subjects. 'When I asked for career guidance at school,' he wrote years later, 'they recommended bricklaying as a good, regular job, although someone did think I might make a good Woolworths manager. Basically, I just wanted to be Gary Cooper.' However, his acting aspirations took a knock when the 16 year-old played a character in his sixties in the East Ham Choral and Dramatic Society production of W. Somerset Maugham's The Sacred Flame and Stamp was mortified when he was singled out for a panning by the reviewer for the local newspaper.

To make a little pocket money, Stamp worked for professional golfer Reg Knight at Wanstead Golf Club. He also received free lessons, but he didn't look back on the experience with much affection in his 1987 autobiography, Stamp Album: 'I was just awfully, terribly frustrated. I wanted to be like Ben Hogan, a tournament pro. I felt this teaching was no good for three pounds a week which didn't even pay for my lunches at the club. If you're just going to teach beginners, you might as well work in a bank. I didn't see how you could love playing golf with a lot of idiots. If you're going to play golf, you want to play with the best. Golf was just a humiliation to me. I knew it would be years. before I'd be any good. I would never have gotten to scratch, never.'

Deciding advertising was a better bet, Stamp worked for a number of agencies in the East End and was soon earning twice as much as his father. Designing ads proved unfulfilling, however. 'I suddenly realised I was just working for the money,' he told an interviewer. 'So I had a few suits and a few shirts - what's the point? I hated it. I was sitting there with a drawing board designing ads just waiting for Friday. Then I got to thinking what I really wanted to do. I decided I would be happy if I were going to work as an actor.'

The sight of James Dean in Elia Kazan's East of Eden (1955) was the tipping point, as Stamp started to think, 'maybe I could actually do this'. He was further galvanised by being rejected for National Service, as he reasoned that he would get a two-year start on any rivals in uniform. 'I thought I'd died and gone to heaven,' he recalled after having been informed that his feet were different sizes, 'two whole years to establish myself before my contemporaries caught up with me.' Without telling anyone at home, he began taking scholarship tests for various acting schools, as he knew that he couldn't afford to study without financial support. Stamp also landed a part-time backstage job at Her Majesty's Theatre and had vivid memories of directing a spotlights on Chita Rivera in West Side Story in 1958. All he needed now was someone to show some faith in him.

Tel and Mo

Stamp's scholarship to the Webber Douglas Academy of Dramatic Art at 30 Clareville Street in South Kensington covered his tuition fees and modest living expenses. As he couldn't pluck up the courage to tell his parents, he pretended that he was still at the ad agency in Cheapside and continued to chip in towards the housekeeping. As the course progressed, Stamp's Cockney accent was refined into the distinctive burr that became a key component to his screen persona.

He also secured an agent when Jimmy Fraser saw him play Iago in an academy production of Othello and he dispatched Stamp to Devon in order to learn the ropes with a repertory company. The next couple of years were spent in the provinces, where Stamp found himself appearing in a different play each week. Back in London, he made his mark in A Trip to the Castle and This Year Next Year (both 1960), with the latter prompting The Guardian to dub him a 'master of the brooding silence'. But it was a four-month touring production of Willis Hall's Second World War drama, The Long the Short and the Tall (which would be filmed by Leslie Norman in 1961 ), that got Stamp noticed.

It also brought him into the orbit of one Maurice Micklewhite, another aspiring actor who had changed his name to Michael Caine.

Grumbling about northerners like Albert Finney, Alan Bates, and Tom Courtenay stealing the best parts as social realism took hold on page, stage, and screen, Stamp and Caine moved into a flat at 64 Harley Street, where they shared an audition jacket and recovered from their nights out with Peter O'Toole, who introduced them to movers and shakers on the London party scene. Stamp also started dating Julie Christie, who was recently profiled in Cinema Paradiso's Getting to Know slot.

Befriending established actors Moray Watson and Anthony Newley, Stamp picked up hints about catching the eye at auditions by doing next to nothing. The advice came in handy when he was pulled out of a rehearsal for a semi-musical entitled Why the Chicken? and told to go the Associated British studio because Peter Ustinov wanted to talk to him about a film.

The Most Beautiful Man in the World

In addition to directing and starring in Billy Budd (1962), Peter Ustinov had also adapted Herman Melville's story about an angelic sailor who is victimised by a sadistic officer aboard the merchant ship, 'The Rights of Man'. Stamp was in awe of Ustinov, who seemed preoccupied when he arrived at the studio. Remembering the advice given him by Caine and Newley about less being more, Stamp clammed up during the screen test, later writing, 'I was as quiet as a corpse. I hardly said a word through the whole test and it seemed to work.'

In fact, he had been noticed by Ustinov's wife, Suzanne Cloutier, who had played Desdemona in Orson Welles's Othello (1951). She told her husband to cast Stamp and he went on to pocket a £900 fee and receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor and a BAFTA nod for Best Newcomer for holding his own on debut against Ustinov and Robert Ryan, as merciless master-at-arms John Claggart. Overnight, Stamp became a star, with Ustinov and Cloutier teaching him the ropes as they travelled the world to promote the picture.

Amidst all the fuss, it was easy to overlook the fact that Stamp had also co-starred with Laurence Olivier, as Mitchell the school rebel, in Peter Glanville's Term of Trial (1962). Initially, Olivier had been unimpressed by the young upstart who had dared to speak back to him. But Joan Plowright (see our Remembering tribute) coaxed her spouse into recognising Stamp's potential and he taught his co-star how to look after his voice and adopt a healthy lifestyle because an actor was basically an artistic athlete.

As Beatlemania broke in 1963, Stamp basked in the glory of his Oscar glow. Seen in all the right places, he became part of the Swinging Sixties scene that was commemorated in David Batty's documentary, My Generation (2017). The title couldn't have been more apt, as Stamp's brother, Chris, had formed a partnership with Kit Lambert to manage The Who, as James D. Cooper recalls in Lambert and Stamp (2014). Indeed, it was Chris who told Terence that he and Christie were the 'Terry and Julie' mention in the Kinks hit, 'Waterloo Sunset'. However, composer Ray Davies has always insisted his choice of names was purely coincidental.

By 1964, Stamp was dating supermodel Jean Shrimpton, who would appear in Peter Watkins's Privilege (1967) before being played by Karen Gillan in John McKay's We'll Take Manhattan (2012), which chronicled her relationship with photographer, David Bailey (Aneurin Barnard). Bailey snapped Stamp for his book, Box of Pin-Ups (1964). But it was with rival shutterbug, Terence Donovan, that Stamp opened the trendy Trencherman canteen in Chelsea, which exclusively served nursery food.

Stamp was so wrapped up with becoming a 60s icon that he had little time for acting. In December 1964, however, he opened on Broadway in Bill Naughton's play, Alfie, about a philandering Cockney chauffeur. Despite positive reviews, the show only ran for 21 performances and Stamp turned down the lead in Lewis Gilbert's 1966 film adaptation, much to the relief of his erstwhile flatmate, who drew a Best Actor nomination at the 1967 Oscars for his career-making turn in Alfie.

After a three-year absence, Stamp returned to films as amateur lepidopterist Freddie Clegg in William Wyler's adaptation of John Fowles's The Collector (1965). Having read the book before its publication, Stamp was desperate to play the social misfit who abducts a woman and keeps her in his cellar. However, he knew he looked nothing like the character in the text and was amazed when Wyler cast him because 'we're not gonna make the book. We're gonna make a love story.'

As he had dated Samantha Eggar before she was cast opposite him, the shoot ranked among the most enjoyable of Stamp's career and he was rewarded with the Best Actor prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Unfortunately, his next assignment proved more fraught, as much of his part as knife-throwing sidekick Willie Garvin in Joseph Losey's take on the Peter O'Donnell comic strip, Modesty Blaise (1966), was cut after Dirk Bogarde (an old friend of Losey's) had complained that he didn't have enough to do as Monica Vitti's nemesis, Gabriel. Ironically, Michael Caine and Mia Scala had originally been cast as the troubleshooters for director Sidney Gilliat, but he sold the rights to producer Joseph Janni, who also cast Stamp as Sergeant Francis Troy in John Schlesinger's adaptation of Thomas Hardy's Far From the Madding Crowd (1967).

Julie Christie starred as Bathsheba Everdene, while Alan Bates and Peter Finch were cast as shepherd Gabriel Oak and farmer William Boldwood, who compete for her affections with the dashing dragoon in his red tunic. Schlesinger had wanted Jon Voight for the role and had tried to make life hell on set for the left-handed Stamp by insisting that he did his sword-twirling flourishes with the other hand, as dragoons in the 1860s had been exclusively right-handed. Taking pity on Stamp, cinematographer Nicolas Roeg worked with him after hours to ensure that Schlesinger got the coverage he wanted. Yet, despite them rubbing along so well, Roeg never cast Stamp in a single film when he became a director.

The press made much of the old flames working together, but Stamp later told a reporter, 'On the set, the fact that she had been my girlfriend just never came up. I saw her as Bathsheba, the character she was playing, who all the men in the film fell in love with. But it wasn't hard, with somebody like Julie.' Yet, despite the spark between them, the film disappointed at the box office and Stamp's confidence took a knock. Having already declined the role of King Arthur in Joshua Logan's Camelot (1967) because he felt he couldn't sing (and refused to be dubbed), he turned down George Cukor's offer to play Romeo to Audrey Hepburn's Juliet. However, it was Orson Welles who failed to come through where Divine Words was concerned, as he couldn't raise the money. But Stamp did get to witness Awesome Orson holding court in a Paris hotel.

He blamed his misfortunes on Schlesinger, who hadn't struck him as 'a guy who was particularly interested in film'. Stamp also told The New York Times that he didn't necessarily see himself as a movie star. 'You can't ignore film acting if you want to reach a large public,' he averred. 'But I prefer the stage. There's no comparison, really. I can never understand how people can go to Hollywood and become actors. "Where did you study?" I ask. They say, "Here." It must be a terribIy difficult thing. How do you ever get to know about things like timing and characterisation? The stage is honest, isn't it. You and I know that some of the highest paid film stars in the world can't act their way out of a paper bag. But on the stage when the curtain goes up you're on your own. It's not just make-up. That's the moment of truth really and if you can't do it, where are you?'

Six decades later, this sounds like the posturing of a cocky young buck. But Stamp was eager to stretch himself and agreed to play Dave Fuller opposite Carol White in Ken Loach's feature bow, Poor Cow (1967), because the director wanted his cast to improvise rather than declaim scripted lines. At first, Stamp found the method challenging and felt that Loach's habit of feeding lines was too intrusive. 'Before a take,' he later recalled, 'he'd say something to Carol and then he would say something to me, and we only discovered once the camera was rolling that he'd given us completely different directions. That's why he needed two cameras, because he needed the confusion and the spontaneity.'

The pair didn't see eye to eye politically, either. Although Stamp was hardly in agreement with fellow West Ham supporter Alf Garnett in the BBC sitcom, Till Death Us Do Part (1965-75). However, they were both at the 1966 World Cup Final, as is revealed in Bob Kellett's The Alf Garnett Saga (1972). Indeed, Stamp saw all six of England's games and later narrated the 13-part series, History of Football: The Beautiful Game (2002).

Feeling frustrated after three difficult projects, Stamp decided to follow in the footsteps of his hero, Gary Cooper, and make a Western. However, the critics savaged Silvio Narizzano's Blue (1968), in which the adopted Azul turns against the Mexican bandit family that had adopted him when they attack some settlers in 1880s Texas. Perhaps he might have been better advised to have taken more seriously a meeting with James Bond producer Harry Saltzman, who was seeking a replacement for Sean Connery, who had decided to stop playing 007 after Lewis Gilbert's You Only Live Twice (1967). As Stamp later revelled in revealing, 'I think my ideas about it put the frighteners on Harry. I didn't get a second call from him.'

Jean Shrimpton also stopped taking Stamp's calls in 1968 after she discovered that he had been receiving a percentage of her salary for organising her promotional work. She felt betrayed, although he always insisted, 'Jean was totally wrong about the money. I was keeping 10 per cent but had intended to present her with a lump sum as a surprise. Stealing never was my style.'

Needing a change of scenery, as the London scene shifted from peace and love to protest, Stamp accepted the title role in 'Toby Dammit', Federico Fellini's contribution to the three-film Edgar Allan Poe anthology, Spirits of the Dead (1968). Playing a dissolute actor who is lured to Rome by the prospect of getting a Ferrari for shooting a movie, he found himself entirely on Fellini's wavelength, as he was given scope to make suggestions and experiment. 'Fellini embodied the transcendent,' Stamp declared. 'He was more than a great director, he was like the guru.'

This statement is ironic because Fellini introduced Stamp to the Indian philosopher, Jiddu Krishnamurti, who taught him about consciousness and meditation. The director's astrologer, Contessa Vadna Passigli-Scaravelli, also guided Stamp through a series of breathing rituals and yoga exercises that he continued to do for the rest of his life. She also convinced him to become a vegetarian and he later published cookbooks for those who were gluten and/or lactose intolerant.

Having dated both Rita Hayworth and Brigitte Bardot, Stamp got to spend time with another youthful crush, Silvano Mangano, whom he had seen in Giuseppe De Santis's neo-realist classic, Bitter Rice (1949). She had been cast as the mother of the family with whom Stamp's stranger comes to stay in Pier Paolo Pasolini's Theorem (1968). He succeeds in seducing every member of the household in a scathing indictment of bourgeois morality and hypocrisy.

As Pasolini had no English, Stamp found the shoot tricky to negotiate. He recalled, 'Pasolini told me: "A stranger arrives, makes love to everybody, and leaves. This is your part." I said: "I can do that!"' However, Pasolini gave him little or no direction and Stamp discovered that he was filming with a secret camera. 'I realised,' he later explained, 'he was trying to get something from me when I wasn't performing. He wanted a kind of being-ness.'

Nelo Risi worked in a different way again, when he cast Stamp as French poet Arthur Rimbaud in A Season in Hell, which was shot during the Italian sojourn but held back until 1971, by which time Stamp had taken the title role in Alan Cooke's The Mind of Mr Soames (1970), Amicus's adaptation of a Charles Eric Maine novel about a 30-year coma victim who is awakened live on television and exploited as a curio. By the time Stamp returned to London, the mood had turned sombre, as though people had started to realise that a decade that had offered so much hope in bringing socio-cultural change was going to end with the world being riven by racial injustice, economic disparity, and Cold War conflict.

Reflecting decades later, Stamp conceded: 'To be frank with you, I do think about my career as before and after Fellini, because that was such a landmark for me. I knew he'd written 'Toby Dammit' for O'Toole and I knew Peter wouldn't do it. I knew I was the second choice. But he loved me and the price was that I love him back, which wasn't hard. So those four weeks were a real rush for me and it was only because of what had happened to me during the Fellini shoot that I was able to give the kind of performance in Teorema that I was able to. Fellini got the best acting out of me I'd ever done at that point. So by the end of that experience, I was no longer acting. I was just being, which prepared me for the experience with Pasolini, who didn't want acting. Pasolini used to film me without me knowing with his own camera, when I wasn't on set, when I wasn't acting. It didn't take me long to realise what he was doing. He just wanted me being, just being myself. Being present in the present. That was a new strata of performance for me.'

It was also going to be the guiding mantra of the ensuing decade, as Stamp took stock of his life and his place within contemporary cinema. 'When the 1960s ended,' he said years later, 'I just ended with it. I remember my agent telling me: "They are all looking for a young Terence Stamp."' But the 31 year-old real thing had somehow slipped out of vogue.' That's what turned me inwards,' he remembered. 'If I'd just been a little bit more dumb, I would have chased after the next supermodel.' But he decided to go to India and rediscover himself.

As revealed in Paul Saltzman's Meeting The Beatles in India (2020) and Ajay Bose's The Beatles and India (2021), the Fab Four had spent time with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1968. So, it was apt that the day Stamp flew out of Britain happened to coincide with the famous Rooftop Concert that was filmed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg for Let It Be (1970) and restored by Peter Jackson for The Beatles: Get Back (2021). Indeed, as he lived round the corner from Apple's offices in Savile Row, Stamp had popped in to say his goodbyes en route to the airport. The band would have been broken up for seven years by the time he returned.

On the Comeback Trail

As a boy, Stamp had been impressed by Edmund Goulding's adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham's The Razor's Edge (1946), in which Great War veteran Tyrone Power passes up a lucrative job to live in bohemian Paris. When the Jazz Age fails to raise his spirits, however, he abandons fiancée Gene Tierney to seek enlightenment in the Far East. While many would have considered this a romantic fantasy in 1969, it seemed an ideal solution for the disillusioned actor and he spent much of the next eight years meditating at an ashram in Pune and studying the teachings of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.

'A lot of maturing happened when I was out of work and travelling,' he confessed. 'There was less temptation to become a caricature of myself.' As he told GQ: 'When I have to do these junkets and I'm being interviewed by journalists around the world, I often get asked, "Why did you retire so early?" Which is very romantic, but I'm afraid it wasn't like that at all. I don't know why it ended. There's no real reason why it ended. I think I was heavily identified with the era, and when the era finished, I ended with it. It wasn't of my choosing. But I just chose not to give up the ghost. I just chose to think, "So this is just a few months." And then it was a year, and I thought, "Well, this is a year…" In the back of my mind, there was this feeling that the call will come. And when the call comes, I want to be ready.'

Stamp once joked that 'they couldn't give me away'. But it came as a shock to discover how far his star had fallen when David Puttnam offered him just £3000 to appear in Claude Whatham's That'll Be the Day (1973). He did make a couple of films in 1975, joining Laura Antonelli and Marcello Mastroianni in Giuseppe Patroni Griffi's Roaring Twenties ménage, The Divine Nymph, and Jeanne Moreau in Jérôme Laperrousaz's Hu-Man, in which a nervous actor has to face his fear of going on live television.

He even took a co-producer credit on the latter, but it was barely seen. This goes double for Philippe Mordacq's Black-Out (1977), which was seemingly a drama about alcoholism in which Stamp's character was called Edgar Poe. He may well have carried on fetching up in such obscure titles had not a telegram addressed to 'Clarence Stamp' at the 'Rough Diamond Hotel' reached him at the Blue Diamond Hotel near the ashram some time in 1976. Much to his astonishment, the message was from his agent and it read: 'Would you be prepared to come back to London to talk to Richard Donner about a part in Superman ? You have a scene with Marlon Brando.' This was the clincher.

The sequence comes at the beginning of the film, as Jor-El (Brando) banishes Kryptonian criminals General Zod (Stamp), Ursa (Sarah Douglas), and Non (Jack O'Halloran) to the Phantom Zone. DC Comics fans were intrigued to see that Stamp had remodelled the balding villain by sporting black hair and a goatee and the look went down so well that it was used in subsequent comic-books. However, Stamp was restricted to a cameo, as the action centred on the tussle between Superman (Christopher Reeve) and Lex Luthor (Gene Hackman) and the relationship between Daily Planet reporters Clark Kent and Lois Lane (Margot Kidder).

Stamp later admitted that meeting such a hero as Brando turned out to be something of a disappointment, as he hadn't bothered learning his lines, which were printed on cue cards dotted around the set. 'Brando is a bit like Fellini.' Stamp mused. 'He's like a flea. You have to kind of catch him when you're in town. I always called Marlon when I was in LA, but I only actually caught up with him a few times. But he was just one of the funniest guys in the world. I thought the world of him. That was the longest time we spent together, because we were together on the set for the whole 12 days.'

Problems with script length and the budget led to the scenario being split in half and Zod and his evil cohorts become more pivotal to Richard Lester's Superman II (1980). The scene in which they bust into the White House and he calmly orders the President (E.G. Marshall) to 'Kneel before Zod!' became one of the highlights of the franchise. Such was the affection with which Stamp viewed the films that he agreed to introduce the BBC's 50th anniversary radio tribute, Superman on Trial, in 1988. Moreover, he also agreed to voice Jor-El in 23 episodes of Smallville (2001-10). Man of Steel aficionados among the Cinema Paradiso membership are also going to want to rent Superman II: The Richard Donner Cut (2006), which incorporated footage shot by Donner before the project was re-assigned.

Excited to be back in circulation, Stamp played Dracula in London in 1978, although the reviews were anaemic. He had more luck in tandem with Vanessa Redgrave in Henrik Ibsen's The Lady From the Sea, the following year. But Stamp now viewed himself principally as a screen actor and relished the challenge of playing Prince Lubovedsky in Peter Brook's take on Gurdjieff's Meetings With Remarkable Men (1979), which was mostly filmed in Afghanistan. The same year also saw Stamp return to Italy to be directed by a woman for the first time, as he co-starred with Jacqueline Bisset as a woman facing repeated heartache in Armenia Balducci's Together?

Despite the acclaim and the renewed interest generated by Zod, Stamp didn't cash in by taking well-paid roles in big-budget blockbusters. He accepted that he was now a character player and that he would occasionally have to take the odd role to pay the rent, as he never bought a home of his own. Thus, he doubled up as Tashkinner and Skinner in Juan Piquer Simón's Jules Verne's Mystery on Monster Island (1981) and played Padre Andrea being elevated to the Papal Throne as Giovanni Clemente I in Marcello Aliprandi's Vatican Conspiracy (1982), which was based on the sudden death in 1978 of Pope John Paul I. Stamp manages to be both humble and imposing and it's to be hoped that this thriller is given a release on disc following the success of Edward Berger's Conclave (2024). But it made little impact at the time, even though Stamp was about to embark upon one of the most notable periods of his career.

Classics and Curios

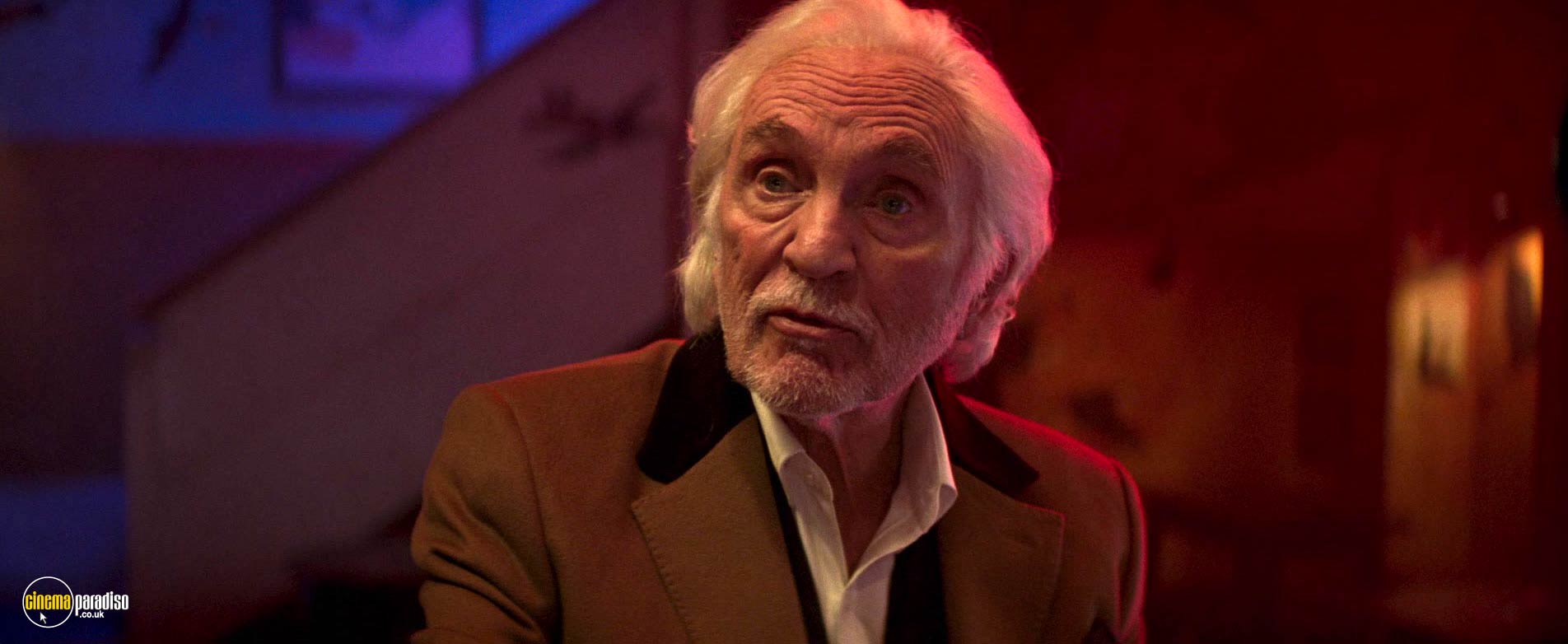

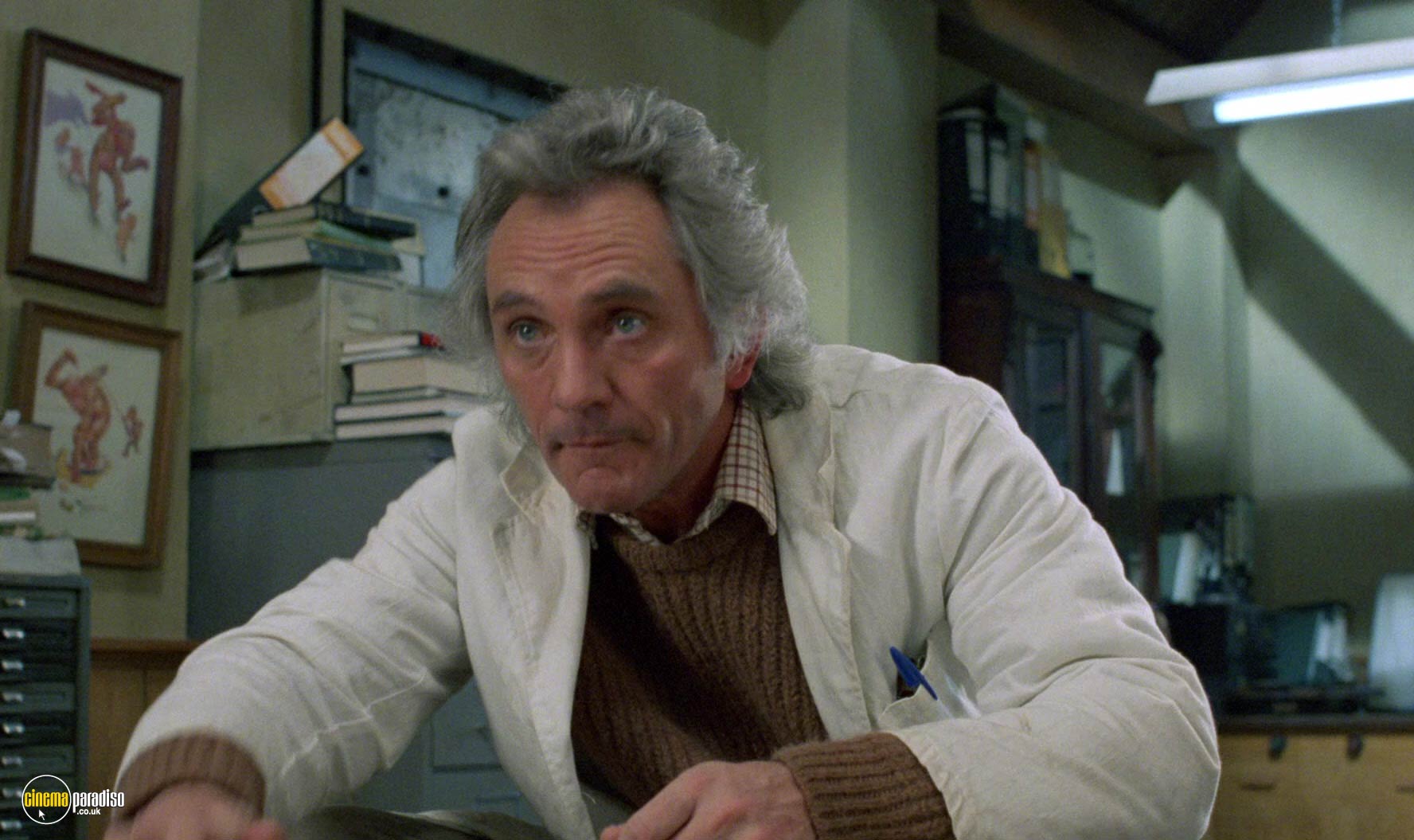

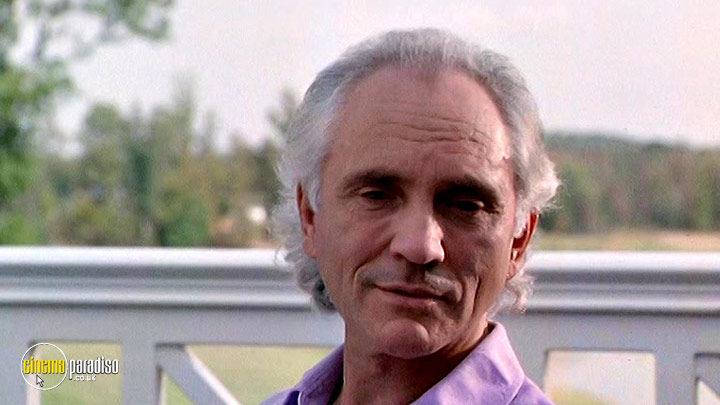

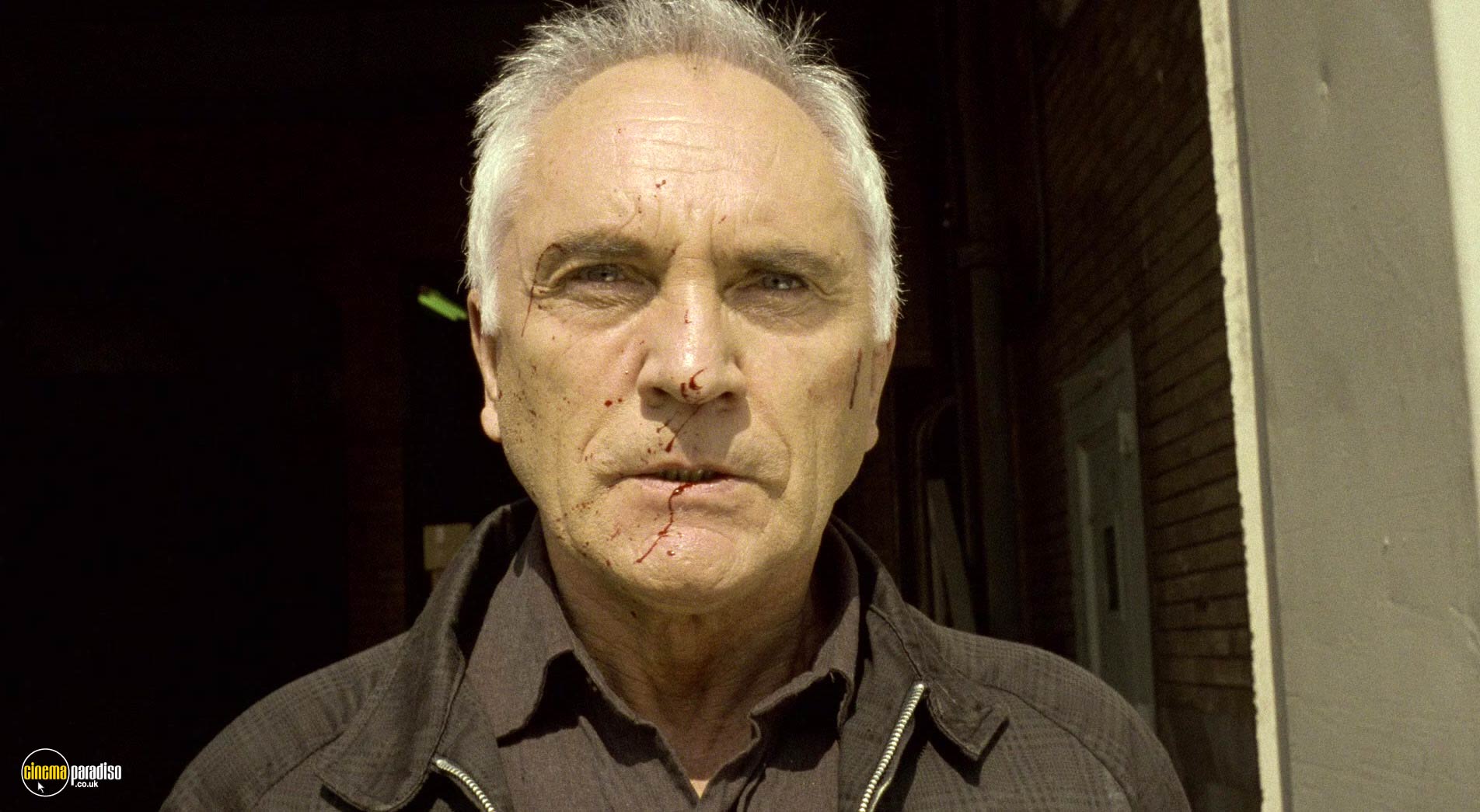

While trying to find his feet, Stamp took the lead in Chessgame (1983), a spy series based on the novels of Anthony Price. However, he 'hated appearing on TV' and sought out big-screen assignments like Neil Jordan's adaptation of Angela Carter's The Company of Wolves, in which he took an uncredited cameo as The Devil. Even more impressive, however, was his turn as Willie Parker, a London criminal who is snatched from his Spanish safe house a decade after squealing to the police in Stephen Frears's The Hit (both 1984). With John Hurt and Tim Roth also excelling as the hitman and his sidekick trying to intimidate Stamp, this crime classic really should be on disc in the UK.

Cinema Paradiso users can see a rare Stamp excursion to Hollywood in Ivan Reitman's Legal Eagles (1986), as art gallery curator Victor Taft becomes involved in a case involving rival lawyers Tom Logan (Robert Redford) and Laura Kelly (Debra Winger) and a painting that performance artist Chelsea Deardon (Daryl Hannah) claims to own when she is accused of stealing it. While in California, Stamp heard that his mother had died (having lost his father two years earlier). Unable to leave for the funeral, he started writing down his memories of family life and these formed the basis of his first volume of autobiography, Stamp Album. In later years, this would be followed by Coming Attractions (1987), Double Feature (1988), Rare Stamps (2012), and The Ocean Fell into the Drop.

Suddenly alone, Stamp threw himself into work. He joined Elisabeth Shue to play Dr Steven Phillip in Richard Franklin's chimpanzee chiller, Link, before heading to Norway to play an artist named Edward in Vibeke Løkkeberg's Hud (both 1986), which saw the director play a woman who gives birth to her stepfather's child. Stamp then upped the ante to essay Prince Borsa in The Sicilian, Michael Cimino and Gore Vidal's adaptation of Mario Puzo's novel about an infamous brigand (Christopher Lambert) whose career had been chronicled with greater finesse in Francesco Rosi's Salvatore Giuliano (1962).

Staying in the Hollywood mainstream, Stamp based British banker Sir Larry Wildman in Oliver Stone's Oscar-winning Wall Street (1987) on Sir James Goldsmith. The knowing cameo was commended and Stamp was further praised for his work as rancher John Tunstell in Christopher Cain's Young Guns (1988), a Brat Pack Western that co-starred Kiefer Sutherland, Lou Diamond Phillips, Charlie Sheen, Dermot Mulroney, and Casey Siemaszko alongside Emilio Estevez as Billy the Kid.

From the Wild West, Stamp found himself in a futuristic Los Angeles as Newcomer businessman William Harcourt in Graham Baker's sci-fi gem, Alien Nation (1988), which paired James Caan and Mandy Patinkin as LAPD detectives Matthew Sykes and Sam Francisco. Becoming one of Hollywood's go-to villains, Stamp was next seen as pop star-turned-mobster Paul Hellwart trying to manipulate gambler Peter Berg in Kurt Voss's Genuine Risk (1990). But this shady picture was too little seen, as was the case with Pilar Miró's Beltenbros (aka Prince of Shadow, 1991), even though it won a Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival for Outstanding Artistic Achievement. This time, Stamp cut a dash as Darman, a British hitman who returns to post-Civil War Spain to eliminate a treacherous Communist Party bigwig.

Around this time, Stamp started work on his directorial debut, only for the $5 million production to close down after three weeks. Having taken a couple of years off to take stock, he returned in front of the camera as Jack Schmidt, a villain who abducts the son of a former cohort (Kim Basinger) to ensure she participates in a heist in Russell Mulcahy's The Real McCoy (1993). More memorable, however, was Stamp's collaboration with another Australian director, Stephan Elliott, who cast him as trans woman Bernadette Bassenger in The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), which co-starred Guy Pearce and Hugo Weaving as Adam Whitely and Anthony Belrose, who are better known by their drag queen names, Felicia Jollygoodfellow and Mitzi Del Bra.

'I thought it was a joke,' Stamp later mused on being offered the part, 'but a woman friend of mine just happened to be present when I was getting calls from my agent about the script, and she pointed out to me in a very incisive way that my fear was out of all proportion to the possible consequences. But it wasn't a fun thing, or anything I was looking forward to. It was, "F**k me, this is the last thing in the world I want to do: be in f**king Australia with paparazzi." It was like a nightmare. But it was only when I got there, and got through the fear, that it became one of the great experiences of my whole career. It was probably the most fun thing I've ever done.'

Quite rightly, Tim Chappel's costumes won the Academy Award, while Stamp himself drew Golden Globe and BAFTA nominations for Best Supporting Actor. He later claimed that it would have been a lie if he had not taken on the challenge the film had thrown down. But his death means that he won't now be able to reprise the role in the sequel that Elliott had announced in the summer of 2024.

Following such a career-defining hit, Stamp rather withdrew from the limelight for a couple of years. Few saw him as London publisher Edward Lamb in Bernard Rapp's Limited Edition (1996) or as club owner Fred Moore competing with crooner Jack Hanaway (Denis Leary) for the affections of singer Vicki Rivas (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón) in Juan José Campanella's Love Walked In (1997). He was more visible as the host of the TV horror series, The Hunger (1997-2000) before he passed the duties on to David Bowie for the second season and went off to play a tantric sex therapist named Balthazar, who comes between newlyweds Maria (Sheryl Lee) and Joseph (Craig Sheffer) in Lance Young's Bliss (1997).

This slice of erotica chimed in with Stamp's own philosophies and he reunited with Sheryl Lee as Kozen, a Zen Buddist from the Philippines who guides a couple of fortysomethings through a mid-life crisis in

Roger Young's Kiss the Sky. He had a higher profile outing as Terry Stricter, the MindHead mentor of film star Kit Ramsay (Eddie Murphy), who is unknowingly shooting a movie for opportunistic producer, Bobby Bowfinger (Steve Martin) in Frank Oz's lively farce, Bowfinger (both 1999).

This proved to be a busy year, as Stamp guested as Supreme Chancellor Finis Valorum in George Lucas's Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (1999). He didn't enjoy the experience, however. 'It was just bland really,' he later reported. 'He's obviously a visionary, a really smart man, but he's not the kind of film-maker that I'm interested in. It's about kids and toys and special effects. I'm sure it's fascinating in his head. I don't think he's interested in actors, frankly. I suppose I should talk to other actors about him, but I haven't, so I don't know. With me, it was the opposite of the law of like kinds I'm afraid.'

Stamp found Steven Soderbergh to be a much more compatible collaborator when he signed up to play Wilson, a London crook who travels to Los Angeles to investigate his daughter's death in The Limey (1999). What made this riff on Get Carter (1973) all the more fascinating was the fact that Soderbergh cut in footage from Poor Cow to show the 'younger Wilson' with his adoring child. Having been nominated for Best Male Lead at the Independent Spirit Awards, Stamp rose to a challenge set by his director.

'I was inspired by Soderbergh to write a loose sequel to The Limey,' Stamp later revealed. 'It's not a sequel, but he wanted to make a thriller in London and he gave me this wonderful idea and I wrote a screenplay of it, which he loved. But between his giving me the idea and me writing the screenplay, he decided that he was going to retire. Whenever I bump into him, he says "You should do it. You wrote the screenplay, you've obviously got the vision," So he's lumbered me with that!'

He was even more forthcoming with another interviewer: 'It's not a direct sequel. When I reviewed the movie after a lot of writers passed on it, including Tom Stoppard, I saw that The Limey was a real complete circle. So what I did was, I took the character of Wilson and took Steven's idea of a vehicle for Julie Christie and myself. Wilson has just completed a 25-year sentence, having been put behind bars by his best friend, who betrayed him and while he was behind bars he's married the girl he was always in love with. So he's had 25 years to think about how he's going to wreak vengeance upon this guy and how he's going to get the girl back. We start with the first day of freedom and those two agendas. It's like a canvas, the story of enduring love, but the canvas is stretched over this very violent revenge story.' Clearly, one for the tantalising 'If Only' file of unmade movies!

Leaving His Mark

Although Stamp remained in demand for the next quarter of a century, he never hit the heights of The Limey again. However, he did work with Soderbergh again, in a cameo as himself aboard a plane in Full Frontal (2002), while further revisited his past the same year in Damian Pettigrew's award-winning documentary, Fellini: I'm a Born Liar. He would also later figure in Marina Zenovich's Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired (2008). Moreover, Stamp also cropped up in the occasional wannabe blockbuster, like Antony Hoffman's Red Planet (2000), in which he played science officer Dr Bud Chantilas alongside Val Kilmer and Carrie Anne Moss.

Back in Blighty, Stamp was splendidly imposing in Stuart Urban's Revelation as Magnus Martel, the family head seeking a safe way to dispose of a Knights Templar artefact dating from 50AD known as 'The Loculus'. He also guyed his own image, as John, the handsome actor in Yvan Attal's My Wife Is an Actress (both 2001) who makes a jealous journalist (Attal) fear that he will seduce his actress wife (Charlotte Gainsbourg) when they make a film together. But, around this time, the 64 year-old Stamp sprang one of the biggest surprises of his career when he got married on New Year's Eve 2002 to Elizabeth O'Rourke, an Australian pharmacist who was 29 years his junior. The union lasted six years, with Stamp resuming his nomadic bachelor lifestyle.

There's a faint anti-Theorem vibe in David Zucker's My Boss's Daughter, as Tom Stansfield (Ashton Kutcher) comes to regret agreeing to house-sit for Lisa (Tara Reid), the daughter of his domineering publisher boss, Jack Taylor (Stamp). And the printed word also proved central to Gorman Bechard's The Kiss, as editor Clara Thompson (Françoise Surel) persuades grieving author Philip Naudet (Stamp) to finish the novel he had abandoned on his wife's death. But it's spooks rather than books that dominate Rob Minkoff's The Haunted Mansion (all 2003), a feature based on a Disneyland attraction that cast Stamp as the ghostly butler, Ramsley.

The plan is for Samuel Fish (Stamp) to bite the dust in Charley Stadler's Dead Fish (2004), but a mobile phone switch puts Lynch the hitman (Gary Oldman) on the wrong track and draws him into the orbit of foul-mouthed loan shark, Danny Devine (Robert Carlyle). Mix-ups are at a premium in Rob Bowman's Elektra (2005), however, as a Marvel comic-book provided Stamp with the unusual role of Stick the blind martial arts master mentoring Elektra Natchios (Jennifer Garner), who had first been seen in Mark Steven Johnson's Daredevil (2003) and who would return in Shawn Levy's Deadpool & Wolverine (2024).

An editorial decision left Stamp's cameo alongside Brad Pitt and Angelin Jolie in Doug Liman's Mr & Mrs Smith on the cutting-room floor. But he was present and correct as Baker, the Great War veteran who lost everything in the Wall Street Crash in Julia Taylor-Stanley's These Foolish Things (both 2005), which chronicles the love triangle that forms around aspiring 1930s actress Zoë Tapper, screenwriter David Leon, and director Andrew Lincoln.

Abraham Lincoln was still four years away from becoming president when the 1857 Mountain Meadows massacre of the Baker-Fancher wagon train took place in Utah. Stamp plays Brigham Young, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Christopher Cain's September Dawn (2006), which seeks to reapportion blame for the slaughter.

The busiest year of Stamp's later career started with him playing Pekwarsky, a bullet maker and non-Fraterity rogue agent in Timur Bekmambetov's actioner, Wanted, which was headlined by Angelina Jolie and James McAvoy. Then, having been the storyteller in Tanc Sade's short, Flowers and Weeds, Stamp stole scenes in a pair of comedies, as KAOS boss Siegfried in Peter Segal's Get Smart and as positivity guru Terrence Bundley in Peyton Reed's Yes Man - a feat made all the more impressive by the fact that the respective leads were taken by Steve Carell and Jim Carrey.

Completing 2008 was Bryan Singer's Valkyrie, a recreation of the Stauffenberg Plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler that not only saw Stamp playing key conspirator Ludwig Beck, but which also had him (as a child of the Blitz) serving as an adviser on the bomb-damaged settings. During a three-year absence from filming, Stamp voiced Captain Severus in Martyn Pick's British animation, Ultramarines: A Warhammer 40,000 Movie (2010). But he was back before the camera as Thompson, a senior figure in the eponymous body making life complicated for Democratic congressman David Norris (Matt Damon) in George Nolfi's adaptation of Philip K. Dick's The Adjustment Bureau (2011).

Overcoming his fear of singing on screen, Stamp took the role of grumpy Newcastle husband Arthur in order to work with Vanessa Redgrave again and earned a BAFTA nomination for his efforts in Paul Andrew Williams's Song For Marion (2012), which Cinema Paradiso recommends members view in a double bill with Stephen Walker's charming documentary about a senior citizen choir, Young@Heart (2006). However, Stamp was back to his shifty ways as Interpol informant Samuel Winter in Jonathan Sobol's forgery thriller, The Art of the Steal (2013).

A pair of Tim Burtons followed, as Stamp was cast as scathing art critic John Canaday in the Margaret Keane biopic, Big Eyes (2014), and as Abraham Portman recalling his troubled childhood in Wales in Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children (2016). Having thus far resisted the celebrity whodunit, Stamp marked his 80th year by playing Chief Inspector Taverner in Gilles Pacquet-Brenner's atmospheric Agatha Christie puzzler, Crooked House (2017), which also starred Glenn Close, Christina Hendricks, and Gillian Anderson.

Also released in 2017 and teaming Stamp again with Max Irons was George Mendeluk's Bitter Harvest, a tale about Ukrainian resistance to the Kremlin's brutal 1930s collectivisation policy that caused the octogenarian to have what he described as a 'near-death experience' when he was badly injured when the horse he was riding slipped and fell on him. Heroically, he returned to the screen as the Norse god, Odin, to guide a princess (Anna Demetriou) in her efforts to reclaim her usurped throne in David L.G. Hughes's Viking Destiny (2018). He even found his way on to Netflix for the only time as billionaire Malcolm Quince in Kyle Newacheck's Murder Mystery (2019), which starred Adam Sandler and Jennifer Aniston as NYPD cop Nick Spitz and his whodunit-loving hairdresser wife, Audrey. They would crack a second case in Jeremy Garelick's Murder Mystery 2 (2023) and one wonders whether there are more on the way.

Having guested as Giacomo Paradisi in the 2020 'Tower of Angels' episode of the BBC's adaptation of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials (2019-23), Stamp played The Silver Haired Gentleman in Edgar Wright's Last Night in Soho. As was also the case for former Bond girls Diana Rigg and Margaret Nolan (to whom the film was dedicated), this time-slipping saga turned out to be Stamp's swan song, as he died on 17 August 2025. The camera still loved him, however. As he explained to GQ while discussing his screen technique: 'The camera's my girl. That I didn't have to learn. That was just something that was a gift to me, something that happened the first day I got on a film set. I had that rapport with the camera, and it didn't even have to be considered. It was just a given, really.' Easy when you know how, eh?