Cinema Paradiso is all about the romance of movies. So, what better way to mark Valentine's Day than by celebrating the 1988 Giuseppe Tornatore gem that inspired our name and culminates in the kiss montage that still sends shivers down the spine after 35 years?

It took a while for Cinema Paradiso (1988) to make its mark. Released in Italy at 155 minutes, it proved something of a disappointment and only started finding an audience after the running time was trimmed to 124 minutes. Following its receipt of the Special Jury Prize at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival, it received the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, beating Bruno Nuytten's Camille Claudel and Denys Arcand's Jesus of Montreal in the process.

In 2002, Tornatore reissued the premiere edition as Cinema Paradiso: Director's Cut. Thanks to Arrow, this is available to rent from Cinema Paradiso, as well as the amended theatrical release. Much of the additional action is taken up with a coda after the famous montage of kisses. But we'll say no more for those who have yet to discover this version. Instead, we'll recap the story to put the kiss reel in context.

What's It All About, Alfredo?

On hearing the news that an old friend had died, film director Salvatore Di Vita (Jacques Perrin) thinks back to his childhood in the small Sicilian town of Giancaldo that he has not seen for 30 years. As an eight year-old, Toto (Salvatore Cascio), lived with his war-widowed mother, Maria (Antonella Attili). But he is even more devoted to Alfredo (Philippe Noiret), the projectionist at the Cinema Paradiso, who allows Toto to watch for free from his booth.

Part of Toto's enjoyment comes from watching the audience, who are often more entertaining than the movies, as they get up to all sorts of mischief from spitting over the balcony to shooting gangsters during the bullet-flying car chase in Howard Hawks's Scarface (1932). The patrons also boo the abrupt cuts in the action that Alfredo has been forced to make on the orders of Father Adelfio (Leopoldo Trieste), who seeks to protect his flock from any displays of passion. Alfredo keeps the edits so he can splice them back into the pictures before sending them on to the next cinema. But they fascinate Toto, who is curious as to what they contain.

As Toto spends so much time in the booth, Alfredo teaches him how to operate the projector. One night, however, as they are beaming Mario Mattoli's The Firemen of Viggiù (1949) on to a building in the piazza, the cinema catches fire. Toto rushes in to save Alfredo, but the projectionist is blinded when a reel of flammable nitrate film explodes in his face.

When Ciccio Spaccafico (Enzo Cannavale) uses his win on the football pools to build Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, Toto is hired as the projectionist. As he grows into a teenager (Marco Leonardi), he starts making his own films with a home movie camera. Even though he can't see the results, Alfredo encourages Toto and warns him that he will get his heart broken if he falls for classmate Elena Mendola (Agnese Nano) because her banker father disapproves.

Shortly after the Mendolas move away, Toto is called up for compulsory military service. He tries to write to Elena, but the letters are returned unopened. On being demobbed, Toto returns to Giancaldo, where Alfredo urges him to go to the mainland. Moreover, he instructs him not to allow nostalgia to distract him in following his dream of becoming a director.

Recalling the warmth of that last farewell, Salvatore heads to Sicily for the funeral. He hears that the cinema is going to be demolished for a car park. Alfredo's widow also informs him that he had followed his career with great pride. She gives him the stool he had once stood on to operate the projector and a reel of film.

Back in Rome, Salvatore watches the footage and is moved to tears when he realises it contains all the kisses and lusty snippets that the priest had censored. Alfredo's parting gift commemorates their shared love of cinema and their undying bond of friendship.

Arrivederci Cinema

Making his sophomore feature at a time when attendances were down and the Italian film industry was in the doldrums, Giuseppe Tornatore hoped that Cinema Paradiso would remind people of the simple pleasure of going to the pictures. In small-town Sicily, sitting in the darkness had been a communal experience, as patrons young and old took refuge from the problems of everyday life in images that transported them to different times and places. Gazing at the stars on the silver screen, it seemed as though dreams could come true.

They did for Tornatore, who had been taught how to work the projector at the Cinema Vittorio in Bagheria by Mimmo Pintacuda. He was the inspiration for Alfredo and had once given the aspiring film-maker a camera. Perhaps he was also the source of such Alfredo maxims as, 'Life is not what you see in film. Life is much harder.' Pintacuda didn't lose his sight in a tragic fire, however. Indeed, he became a respected photographer, who specialised in chronicling the lives of Italian immigrants in the United States. Among his albums was one dedicated to the young Tornatore.

Pintacuda died at the age of 86 in 2013 and enjoyed having been immortalised. However, Tornatore had the idea for Cinema Paradiso back in 1977, when he had been asked to help clear out the theatre where he had been working as a projectionist. Despite him wanting Marcello Mastroianni to play Alfredo, the fine French actor Philippe Noiret took the role.

Cinema Paradiso members can order several of his most notable outings, including Agnès Varda's La Pointe courte (1955), Louis Malle's Zazie in the Underground (1960), Alfred Hitchcock's Topaz (1969), Michael Radford and Massimo Troisi's Il Postino (1994), and the Bertrand Tavernier classics, The Watchmaker of St Paul (1973), Let Joy Reign Supreme (1975), The Judge and the Assassin (1976), Une Semaine de vacances (1980), Coup de torchon (1981), and D'Artagnan's Daughter (1994).

I Baci Vietati

Noiret won the BAFTA for Best Actor, while Salvatore Cascio - who was one of 300 Sicilian boys auditioned for the part of Toto - was named Best Supporting Actor. Tornatore took home the awards for Best Original Screenplay and Best Film Not in the English Language. Moreover, Ennio Morricone and his son, Andrea, were recognised for their charming score.

This comes into its own during the kiss montage. But there are lots of other filmic references dotted around the feature. The sharp-eyed will see clips, posters or promotional material across the various versions for William Wellman's Wings (1927), Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel (1930), Charles Chaplin's City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936), the Laurel and Hardy duo of March of the Wooden Soldiers (Gus Meins, 1934) and Block-Heads (John G. Blystone, 1938), Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Victor Fleming's Gone With the Wind (1939), Henry Hathaway's The Shepherd of the Hills, Preston Sturges's Sullivan's Travels (both 1941), Michael Curtiz's Casablanca (1942), Charles Vidor's Gilda (1946), Howard Hawks's Red River (1948), Gordon Douglas's The Black Arrow Strikes (1948), Pietro Germi's In the Name of the Law (1949) and The Path of Hope (1950), Federico Fellini's The White Sheik (1951) and I vitelloni (1953), Robert Rossen'a Mambo, Vittorio De Sica's The Gold of Naples, and Stanley Donen's Seven Brides For Seven Brothers (all 1954).

Cineastes will also recognise Mack Sennett's The Knockout (1914) reducing the audience to hysterics as Charlie Chaplin referees a Fatty Arbuckle boxing bout (see Chaplin at Keystone, 2010), the trailer for John Ford's Stagecoach (1939), and Jean Renoir's The Lower Depths as the film playing when Fr Adelfio rings his bell to signal the scenes he wants cutting. Some will also recognise him tapping his holy water aspergillum to the rhythm of Silvana Mangano singing with a jazz band in Alberto Lattuada's Anna (1951) and the teenage boys on the front row having their pulse rates raised by Brigitte Bardot in Roger Vadim's And God Created Woman (1956). And who spotted that it was Raffaello Matarazzo's Chains (1949) making everybody cry and that the storm blew up during the outdoor screening of

Mario Camerini's Ulysses (1954), starring Kirk Douglas?

Others will know that Alfredo's remarks about the mob relate to Fritz Lang's Fury (both 1936), which stars Spencer Tracy. As does Victor Fleming's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1941), which is screening when the young lovers see each other for the first time because everyone else is ducking down in terror. At another point, the punters grumble because they can't understand Michelangelo Antonioni's Il Grido (1957), although their loudest protests come whenever the action jumps past anything likely to inflame passions. 'Twenty years of going to the cinema,' says one man watching Luchino Visconti's La terra trema (1948), 'and I've never seen a kiss.'

We all know where they went. There are 41 kisses and six saucy snippets in the reel that Salvatore watches back in Rome (where Tornatore cameos as the projectionist). It seems odd that 14 remain unidentified after all this time, but it's more understandable why so many of the Italian films referenced have not been released on disc in this country. These include Flavio Calzavara's Carmela, Alessandro Blasetti's La cena delle beffe (both 1942), Riccardo Freda's The Mysterious Cavalier (1948), and Luigi Comencini's The Emperor of Capri (1949), as well as Clarence Brown's Chained (1934) and Renoir's The Lower Depths.

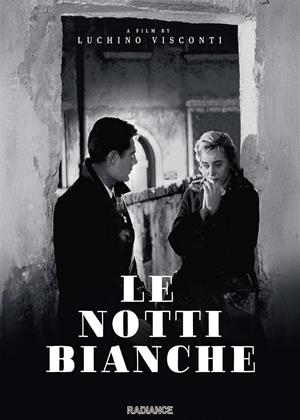

Giuseppe De Santis's Bitter Rice (1949) and Luchino Visconti's White Nights (1957) have been released, but are not currently available. Cinema Paradiso users can, however, order the majority of the censored films. They feature, in the order they appear, Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell in Howard Hawks's His Girl Friday (1940), a pouting Jane Russell in Howard Hughes and Howard Hawks's The Outlaw (1943), Massimo Girotti and Clara Calamai in Luchino Visconti's Ossessione (1942), Charlie Chaplin and Georgia Hale in Chaplin's The Gold Rush (1925), Olivia De Havilland and Errol Flynn in William Keighley and Michael Curtiz's The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Rudolph Valentino and Vilma Banky in George Fitzmaurice's The Son of the Sheik (1926), James Stewart and Donna Reed in Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1946), Anna Magnani and Gastone Renzelli in Visconti's Bellissima (1951), Rosa Costanza and Antonio Arcidiacono in Visconti's La terra trema (1948), Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes in Frank Borzage's A Farewell to Arms (1932), Farley Granger and Alida Valli in Visconti's Senso (1954), Greta Garbo and John Barrymore in Edmund Goulding's Grand Hotel (1932), Spencer Tracy and Ingrid Bergman in Victor Fleming's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1941), and Jean Harlow and Robert Williams in Capra's Platinum Blonde (1931).

Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth could have been there, too. But Tornatore refused to pay the $700,000 demanded for the clip from The Lady From Shanghai (1947). How much easier it was to animate (and slightly tweak) the embraces in the montage in 'Stealing First Base', the 15th episode in the 21st season of The Simpsons (1989-).

It plays as Nikki (Sarah Silverman) gives Bart (Nancy Cartwright) a reviving smacker after he crashes off his skateboard. The films and TV shows highlighted are, Fred Zinnemann's From Here to Eternity (1953), Gone With the Wind (1939), John Ford's The Quiet Man (1952), Disney's Lady and the Tramp (1955), Franklin J. Schaffner's Planet of the Apes (1968), Mark Rydell's On Golden Pond (1981), Jerry Zucker's Ghost (1990), Sam Raimi's Spider-Man (2002), J.J. Abrams's Star Trek (2009), Ron Koslow's Beauty and the Beast (1987-90), William A. Wellman's The Public Enemy (1931), Andrew Stanton's WALL-E (2008), David Fincher's Alien 3 (1992), Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather Part II (1974), and the episode of the sitcom All in the Family (1971-79) featuring a guest turn from Sammy Davis, Jr.

If you think the music sounds familiar, it's the original Morricone melody from Cinema Paradiso. A few films have since pastiched the montage idea, notably Mohsen Makhmalbaf's Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1992) and Daniele Cipri and Franco Maresco's mockumentary, The Return of Cagliostro (2003). Robert Eldredge also compiled a same-sex montage in 2006, but this no longer appears to be available online. For more about the history of LGBTQ+ cinema, see Jeffrey Friedman and Rob Epstein's The Celluloid Closet (1995), while Martin Scorsese proves an excellent guide to the history of Italian cinema in My Voyage to Italy (1999), which references several of the films featuring in Cinema Paradiso.

-

His Girl Friday (1940) aka: Howard Hawks' His Girl Friday

Play trailer1h 32minPlay trailer1h 32min

Play trailer1h 32minPlay trailer1h 32minWalter Burns (Cary Grant), the editor of The Morning Post, sets out to sabotage the plans of ace reporter and ex-wife Hildy Johnson (Rosalind Russell) to marry a dullard who sells insurance.

- Director:

- Howard Hawks

- Cast:

- Cary Grant, Rosalind Russell, Ralph Bellamy

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Outlaw (1943) aka: Geächtet

1h 55min1h 55min

1h 55min1h 55minOut to avenge her brother, Rio McDonald (Jane Russell) finds herself caught between Doc Holliday (Walter Huston), Pat Garrett (Thomas Mitchell), and Billy the Kid (Jack Buetel).

- Director:

- Howard Hughes

- Cast:

- Jack Buetel, Thomas Mitchell, Jane Russell

- Genre:

- Classics, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

Ossessione (1942) aka: Obsession

2h 20min2h 20min

2h 20min2h 20minWhile working at a garage taverna, itinerant Gino Costa (Massimo Girotti) falls for Giovanna Bragana (Clara Calamai) and they plot to murder her husband.

- Director:

- Luchino Visconti

- Cast:

- Clara Calamai, Massimo Girotti, Dhia Cristiani

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Gold Rush (1925) aka: Lucky Strike

Play trailer1h 9minPlay trailer1h 9min

Play trailer1h 9minPlay trailer1h 9minA gold prospector (Charlie Chaplin) becomes enamoured of the dance hall girl (Georgia Hale) who had kissed his cheek to make another customer jealous.

- Director:

- Charles Chaplin

- Cast:

- Charles Chaplin, Mack Swain, Tom Murray

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Play trailer1h 38minPlay trailer1h 38min

Play trailer1h 38minPlay trailer1h 38minSaxon knight Robin of Locksley (Errol Flynn) loses his heart to Lady Marian (Olivia De Havilland), a Norman ward of King Richard, whose brother, Prince John, is ruling tyrannically while he's away on crusade.

- Director:

- Michael Curtiz

- Cast:

- Errol Flynn, Olivia De Havilland, Basil Rathbone

- Genre:

- Classics, Action & Adventure, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Son of the Sheik (1926)

1h 9min1h 9min

1h 9min1h 9minAhmed (Rudolph Valentino) is so besotted with Yasmin the dancing girl (Vilma Banky) that he leaves the security of his father's palace and is kidnapped by his beloved's bandit father.

- Director:

- George Fitzmaurice

- Cast:

- Rudolph Valentino, Vilma Bánky, George Fawcett

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Action & Adventure, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

It's a Wonderful Life (1946)

Play trailer2h 10minPlay trailer2h 10min

Play trailer2h 10minPlay trailer2h 10minA telephone call changes the lives of George Bailey (James Stewart) and Mary Hatch (Donna Reed) in the small New York town of Bedford Falls.

- Director:

- Frank Capra

- Cast:

- James Stewart, Joseph Granby, Donna Reed

- Genre:

- Children & Family, Sci-Fi & Fantasy, Classics, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Bellissima (1951) aka: Beautiful

Play trailer1h 50minPlay trailer1h 50min

Play trailer1h 50minPlay trailer1h 50minWhile slum dweller Spartaco Cecconi (Gastone Renzelli) dreams of building a house for his family, wife Maddalena (Anna Magnani) hopes to turn five year-old daughter into a film star at Rome's Cinecittà studios.

- Director:

- Luchino Visconti

- Cast:

- Anna Magnani, Walter Chiari, Tina Apicella

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

La Terra Trema (1948) aka: La terra trema: Episodio del mare / The Earth Will Tremble / The Earth Trembles

2h 33min2h 33min

2h 33min2h 33minSicilian fisherman 'Ntoni Valastro (Gastone Renzelli) kisses Nedda (Rosa Costanza) after a bumper catch of anchovies. But the locals disapprove of his plans to form a co-operative.

- Director:

- Luchino Visconti

- Cast:

- Antonio Arcidiacono, Luchino Visconti, Antonio Pietrangeli

- Genre:

- Drama, Children & Family, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

A Farewell to Arms (1932)

1h 18min1h 18min

1h 18min1h 18minAmerican ambulance driver Frederic Henry (Gary Cooper) meets British Red Cross nurse Catherine Barkley (Helen Hayes) while serving on the Italian front during the Great War.

- Director:

- Frank Borzage

- Cast:

- Gary Cooper, Helen Hayes, Adolphe Menjou

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Senso (1954) aka: The Wanton Countess

1h 56min1h 56min

1h 56min1h 56minContessa Livia Serpieri (Alida Valli) falls prey to the charms of Austrian officer Franz Mahler (Farley Granger), even though their countries are at war and she knows he is only attracted by her wealth.

- Director:

- Luchino Visconti

- Cast:

- Farley Granger, Alida Valli, Heinz Moog

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Grand Hotel (1932) aka: Grand hotel

Play trailer1h 48minPlay trailer1h 48min

Play trailer1h 48minPlay trailer1h 48minDespite famously wanting to be alone, suicidal Russian ballerina Grusynskaya (Greta Garbo) is intrigued to find gentleman thief Baron Felix von Gaigern (John Barrymore) in her room at a Berlin hotel.

- Director:

- Edmund Goulding

- Cast:

- Greta Garbo, John Barrymore, Joan Crawford

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) aka: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) / Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941)

3h 20min3h 20min

3h 20min3h 20minWhile in the guise of his evil alter ego, 1880s London medic Henry Jekyll (Spencer Tracy) latches on to music-hall barmaid Ivy Peterson (Ingrid Bergman).

- Director:

- Victor Fleming

- Cast:

- Spencer Tracy, Ingrid Bergman, Lana Turner

- Genre:

- Horror, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Platinum Blonde (1931) aka: Gallagher

1h 25min1h 25min

1h 25min1h 25minWell-heeled Anne Schuyler (Jean Harlow) decides to try and make a gentleman out of reporter Stew Smith (Robert Williams) when he publishes a kiss'n'tell story about her playboy brother.

- Director:

- Frank Capra

- Cast:

- Jean Harlow, Loretta Young, Robert Williams

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Romance

- Formats:

-