Few British performers are more steeped in the traditions of the stage and screen than Vanessa Redgrave. Born to renowned actors, she and her famous siblings formed a thesping dynasty that continues to foster talent. So, as she celebrates turning 85 with a damehood, Cinema Paradiso reflects on the career of a rebel who has always had a cause.

Eyebrows were raised when Vanessa Redgrave's name appeared on the New Year Honours List. For five decades, Redgrave has been known for her activism as much as her acting and there was surprise when she accepted a damehood after previously declining the title in 1999.

But few have deserved recognition more, as Redgrave has not only graced her profession for 65 years, but she has always had the courage of her convictions, even when they have impacted upon her art. Her views have often courted controversy, but Redgrave has never taken a backward step and this insistence on doing things her own way has also shaped her distinctive acting style.

Laertes's Daughter

Vanessa Redgrave was born in Blackheath in south-east London on 30 January 1937. Her mother was the admired actress Rachel Kempson, who has a number of films available to view via Cinema Paradiso, including Zoltan Korda's A Woman's Vengeance (1948) and Charles Crichton's The Third Secret (1964). She also co-starred with husband, Michael Redgrave, in Basil Dearden's The Captive Heart (1946) and Lewis Gilbert's The Sea Shall Not Have Them (1954)

Father Michael Redgrave was one of Britain's finest actors and Cinema Paradiso users can treat themselves to dozens of his finest screen outings by tapping his name into the searchline. His grandmother, Zoe Pym, had been a stage actress, and her son, Roy Redgrave had enjoyed success in the West End and was known as 'The Dramtic Cock o' the North' when he sought silent screen fame in Australia. Jack Lee's Robbery Under Arms (1957) is a remake of his last feature.

Redgrave's mother was Margaret Scudamore, who was also an actress. She can be seen in two classics directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, as Mrs Colpeper in A Canterbuy Tale (1944) and as Sister Clodagh's grandmother in Black Narcissus (1947). With this pedegree, there's little wonder that, on hearing of Vanessa's arrival, Laurence Olivier paused the evening's performance of Hamlet at the Old Vic to announce, 'Ladies and gentleman, tonight a great actress has been born. Laertes has a daughter!'

Brother Corin followed in 1939 and sister, Lynn, in 1943. By this time, the family had moved to Herefordshire to avoid the nightly Luftwaffe raids, although Redgrave recalls the blitzes in both London and Coventry in her memoirs. She also claims to have been politicised at the age of eight when she learned about the Nazi death camps. Yet, while her father had once been banned by the BBC for belonging to a group with Communist connections, Redgrave would remain relatively conservative until she was radicalised in the 1960s.

From an early age, she enjoyed putting on shows for her parents with a toy theatre, for which she made scenery and created lighting effects. However, Rachel largely raised the children alone, as the bisexual Michael preferred to live in a nearby cottage with his partner, Bob Michell. Nevertheless, he encouraged Vanessa to create make-believe characters like 'Queen Pretoria' and ensured she got the acting bug when he took her backstage before a performance of The Duke of Darkness.

The young Vanessa hoped to become a dancer, however, and she spent eight years training at the Ballet Rambert School, where Audrey Hepburn was among her classmates. Unfortunately, at the age of 14, she had a growing spurt and realised that she would be too tall at 5ft 11in to become a ballerina. 'I was pretty traumatised about my height,' she later revealed, 'but my parents, particularly my mother, was wonderful about that. She kept encouraging me by telling me I was beautiful when I knew I wasn't.'

Despite her misgivings, Redgrave's looks caught the attention of Walt Disney, who was contemplating a live-action follow-up to his animated gem, Alice in Wonderland (1951). He requested a photograph of Vanessa and invited her to Hollywood for some camera tests. But she was prevented from travelling by a series of blackouts.

Having moved from the Alice Ottley School in Worcester to Queen's Gate School in London, Redgrave began acting in amateur productions. She took the title role in a school version of George Bernard Shaw's Saint Joan (which was filmed with Jean Seberg by Otto Preminger in 1957) and sister Lynn, who didn't always approve of her political affiliations, later claimed, 'Vanessa always thought of herself as Joan of Arc. A bit of the touch of a martyr.'

1966 and All That

Determined to follow in her parents' footsteps, Redgrave secured a place at the Central School of Speech and Drama in 1954. During her first year, she had to share a costume with classmate Judi Dench in order to play Portia in The Merchant of Venice, even she's a foot taller.

She also got to see Marilyn Monroe in the flesh, when she attended playwright husband Arthur Miller's lecture on the bourgeois nature of British theatre. Ironically, the Angry Young Man boom was launched by Redgrave's future husband, Tony Richardson, when he directed John Osborne's Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court in 1956. However, he turned her down when she auditioned for the 1959 screen version, with the part opposite Richard Burton going to Mary Ure.

By the time of its release, Redgrave had made her television debut, alongside her mother, Dora Bryan and Ron Moody on the BBC show, Men, Women and Clothes: Sense and Nonsense in Fashion (1957). She had also discovered the blend of research and emotional truth that became her trademark acting style and it helped her win the prestigious Sybil Thorndike prize on graduation.

Not everyone was convinced about her talent, however, with producer and family friend Simon Relph describing her as 'quite stiff'. But, with a little help from her father, Redgrave managed to make her debuts on film and in the West End in 1958. She was cast as the daughter of the leading surgeon at Graftondale Royal Hospital in Brian Desmond Hurst's medical drama, Behind the Mask, and Michael played Vanessa's father again in A Touch of Sun, an N.C. Hunter play that was also broadcast on the BBC.

In 1959, Peter Hall recruited Redgrave for the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, in which she played Helena opposite Charles Laughton as Bottom. The same season also saw her co-star with Laurence Olivier, Albert Finney and Edith Evans (who had once been her father's lover) as Valeria in Coriolanus.

On working with Redgrave, Hall noted, 'in life, which is true, she is false. In art, which is false, she is true.' This may have been something of a backhanded compliment, but life and art did overlap in 1960, when Redgrave landed her first starring role (again opposite her father) in Robert Bolt's The Tiger and the Horse. This drama about nuclear disarmament had such an impact upon the young actress that she became a regular on Ban the Bomb marches and twice spent the night in a cell after getting arrested in London.

To this point, Vanessa had rather traded on the family name. But she was taken seriously in her own right after her lauded display as Rosalind in Michael Elliott's 1961 Royal Shakespeare Company production of As You Like It. Stern critic Bernard Levin was enchanted by her, so was French director Jean Renoir (several of whose masterpieces are available to rent from Cinema Paradiso - you know what to do). Tony Richardson was so besotted with her as both Rosalind and Katharina in The Taming of the Shrew that he proposed. They married on 28 April 1962 and were soon the proud parents of daughters, Natasha and Joely Richardson.

While friends worried that Redgrave had married a man who (like her father) was bisexual, she threw herself into the union. Such was her determination to be involved in every aspect of Richardson's life that she disguised herself as an old man in order to mingle with the extras in his Oscar-winning adaptation of Henry Fielding's Tom Jones (1963). But, while playing hostess to Richardson's intellectual friends, she steered clear of cinema for much of the decade, as she raised her daughters between productions of Anton Chekhov's The Seagull (1964) and Jay Presson Allen's dramatisation of Muriel Spark's novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1966).

Maggie Smith would win the Academy Award for Best Actress in taking over the title role in Ronald Neame's 1969 screen version. But the part gave Redgrave the confidence to accept three screen roles that would transform her fortunes.

Adapted by David Mercer from his own 1962 BBC play, Morgan: A Suitable Case For Treatment stars David Warner as an eccentric artist who is bent on preventing his upper-class wife, Leonie, from divorcing him and marrying a wealthy gallery owner (Robert Stephens). Striving to capture the mood of Swinging London, Karel Reisz's direction can feel a little strained to modern sensibilities. But Redgrave followed winning the Best Actress prize at Cannes with a BAFTA nomination and the first of her six Oscar nominations.

At the awards ceremony, Vanessa found herself up against her sister, Lynn, who had excelled opposite James Mason in Silvio Narizzano's Georgy Girl. However, they lost out to another British-born actress, Elizabeth Taylor, for her powerhouse performance as Martha in Mike Nichols's adaptation of Edward Albee's play, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf.

In a distinct change of pace, Redgrave made her Hollywood bow as Anne Boleyn in Fred Zinnemann's adaptation of Robert Bolt's A Man For All Seasons (1966), which won the Oscar for Best Picture and afforded an early screen role for Corin Redrave, as William Roper, the son-in-law of Sir Thomas More, who was superbly played by the Oscar-winning Paul Scofield.

Redgrave's third seminal screen role of 1966 cast her a Jane, the young woman who follows photographer Thomas (David Hemmings) to his studio in order to demand that he hands over a potentially incriminating roll of film in Michelangelo Antonioni's Blowup. This project meant a great deal to Redgrave, as she was a huge admirer of the Italian auteur's muse, Monica Vitti, who passed away on 2 February at the age of 90. Cinema Paradiso users can catch up with her collaborations with Antonioni by renting L'aventurra (1960), La notte (1961), L'eclisse (1962) and The Red Desert (1964).

As her presence in Peter Whitehead's epochal documentary, Tonite Let's All Make Love in London (1967), would suggest, Redgrave was now one of Swinging Britain's bright young things. However, Richardson opted not to cast her in Mademoiselle (1966) and, in her absence, he fell in love with leading lady, Jeanne Moreau. He paired the women in The Sailor From Gibraltar (1967) before directing Redgrave in Red and Blue, a musical short that can be found alongside Lindsay Anderson's The White Bus (both 1967) on the BFI release, Red, White and Zero (2018), which includes amongst the extras political cartoonist Abu's animated short, No Arks (1969), which Redgrave narrated.

At Richardson's suggestion, Redgrave turned down Richard Lester's Petulia (1968), which eventually starred Julie Christie, and accepted the role of Guinevere in Joshua Logan's 1967 adaptation of Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe's hit musical, Camelot. Julie Andrews had created the role on stage, but Logan had not been impressed and Redgrave had to polish her singing skills in order to hold her own against Richard Harris and Franco Nero, as King Arthur and Lancelot.

Having learnt Italian as a teenager, Redgrave forged a bond with Nero that was much stronger than her previous flings with Warren Beatty and George Hamilton. Consequently, she divorced Richardson in 1967, although she would play Clarissa Morris alongside her mother, brother and daughters in The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), which earned six BAFTA nominations.

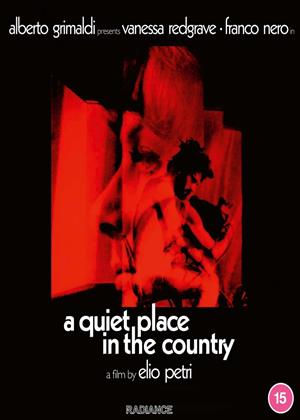

Following her teaming with Nero in Elio Petri's A Quiet Place in the Country (1968), Redgrave gave birth to their son, Carlo Gabriel Nero, who has since gone on to direct his mother in Uninvited (1999) and The Fever (2004). Although their romance cooled, Redgrave and Nero remained friends and occasionally acted together in the likes of David Greene's Bella Mafia (1997), a Lynda La Plante-scripted mini-series that saw Redgrave nominated for a Golden Globe for her turn as a Siclian gangster's wife.

Nero also gave Natasha Richardson away at her wedding to Liam Neeson in 1994. Twelve years later, he and Redgrave tied the knot and continue to share credits, including playing lovers Claire and Lorenzo in Gary Winick's Letters to Juliet (2010) and as Mama and Uncle Topolino in John Lasseter's Cars 2 (2011).

Back in 1968, Redgrave reunited with Karel Reisz to play dancer Isadora Duncan in the biopic, Isadora. Originally running 177 minutes, this much-edited work is available from Cinema Paradiso in the 131-minute cut that was released in the United States. Once again, Redgrave won the Best Actress prize at Cannes and followed another BAFTA nod with her second Oscar nomination. This time, she lost out to Katharine Hepburn and Barbra Streisand, who tied for their performances in Anthony Harvey's The Lion in Winter and William Wyler's Funny Girl (both 1968). However, compensation for Redgrave came in the form of a Golden Globe.

Although the critics were unimpressed with the finished film, Redgrave enjoyed the Swedish shoot of Sidney Lumet's vision of Chekhov's The Sea Gull (1968). But she didn't feel she was right for the part when Robert Altman asked her to play a wealthy spinster who befriends a non-verbal teenager in That Cold Day in the Park (1969) and the role went to Sandy Dennis. Instead, with plenty of family matters to juggle, Redgrave chose to end the decade with a cameo as Sylvia Pankhurst in Richard Attenborough's directorial debut, Oh! What a Lovely War (1969), which won five BAFTAs, including Best Supporting Actor for Laurence Olivier as Field Marshall Sir John French.

A Turbulent Decade

As a mother of three, Redgrave had plenty on her plate. But she managed to juggle her domestic responsibilities with a career that kept the critics off their guard. In 1970, she and Nero invested their own money in Tinto Brass's Dropout and they reunited with the Italian provocateur (who has 14 titles on the Cinema Paradiso books, including the controversial Salon Kitty, 1976) on Vacation (1971).

The same year saw Redgrave fall in love with future James Bond Timothy Dalton when they worked together on Charles Jarrott's Mary, Queen of Scots, which pitched her against Glenda Jackson as Elizabeth I and earned her a third Oscar nomination. She remained in period dress as Andromache in Michael Cacoyannis's The Trojan Women (alongside Katharine Hepburn) and as Sister Jeanne des Anges in Ken Russell's The Devils (both 1971). Revisiting the story told by Jerzy Kawalerowicz in Mother Joan of the Angels (1961), the film sparked huge controversy for its graphic depiction of the events that ensued in the 17th-century convent at Loudon after a hunchbacked abbess became sexually fixated on Fr Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed). Russell won the Best Director prize at Venice, while the furore fed into the press obsession with Redgrave's artistic and political choices.

Having quit the Labour Party because of its support for America's involvement in Vietnam, Redgrave followed her brother into the Trotskyite Workers Revolutionary Party. She ran for Parliament, but only managed to poll a few hundred votes, as the press claimed the WRP was being funded by Muammar Gaddafi and Saddam Hussein. Eventually, the party imploded after leader Gerry Healy was accused of sexually abusing female members, although Corin and Vanessa Redgrave defended him and followed Healy into the short-lived Marxist Party in 1987.

Redgrave's 15-year relationship with Dalton ended when she opted to stand on a picket line rather than spend a Sunday afternoon with him. When six year-old Natasha asked why her mother spent so much time on her political causes, Redgrave explained that she was trying to secure a better future for all children, upon which Natasha replied, 'But I need you now. I won't need you so much then.' In 2007, Redgrave wrote an open letter to Natasha in which she admitted regret at her frequent absences.

Away from the barricades, Redgrave continued to give fascinating performances on screen. Having guested sportingly with Eric and Ernie (for a turn as the Empress Josephine that can be found on Morecambe and Wise: Christmas Specials), she returned to television to play the eponymous New Zealand writer in the BBC serial, A Picture of Katherine Mansfield (1973). She then joined the all-star suspects list, as governess Mary Debenham. in Sidney Lumet's adaptation of Agatha Christie's Murder on the Orient Express (1974). Indeed, Redgrave would play the Queen of Crime in Michael Apted's Agatha (1979), which really should be available on disc in the UK, along with Alan Bridges's Out of Season (1975), in which Redgrave runs a Dorset hotel with her resentful daughter, Susan George.

There was more sleuthing afoot, as Sherlock Holmes (Nicol Williamson) tracks down the kidnapped Lola Deveraux (Redgrave) in Herbert Ross's The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976). But it was her Oscar-winning supporting performance in the title role of Fred Zinnemann's Julia (1977) that dominated the decade and shaped Redgrave's career for several years thereafter.

Adapted from a story in Lillian Hellman's 1973 volume, Pentimento, Alvin Sargent's Oscar-winning screenplay follows Hellman (Jane Fonda) into Nazi Germany, as she delivers the money that her old friend needs to smuggle Jews out of the country. Despite Hellman's account being disbelieved by many (including Zinnemann), the film is tense and thoroughly deserved its 10 Oscar nominations. Following Jason Robards to the podium (for his work as Hellman's mentor, Dashiell Hammett), Redgrave referred to the Jewish Defense League protest outside the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion against her support for the Palestine Liberation Organisation. She thanked Hollywood for having 'refused to be intimidated by the threats of a small bunch of Zionist hoodlums - whose behaviour is an insult to the stature of Jews all over the world and to their great and heroic record of struggle against fascism and oppression.'

Accused of anti-Semitism in the media, Redgrave hit the headlines again a few weeks later, when a Los Angeles screening of Roy Battersby's documentary, The Palestinian (1977) - which Redgrave had narrated and sold her house to finance - was delayed by a bomb blast at the theatre. And there would be further opprobrium when Redgrave was cast as French musician and concentration camp survivor Fania Fénelon in Daniel Mann's Playing For Time (1980). Opponents accused her of desecrating 'the memory of the martyred millions'. But, as a victim of the House UnAmerican Activities Committe's witch-hunt into Communism in postwar Hollywood, screenwriter Arthur Miller defended her casting and her right to hold her political views.

Her performance brought Redgrave an Emmy, but many felt that her career had suffered as a result of her outspoken stance, as she lost a number of high-profile roles because producers refused to hire her. But she ended the decade with roles in two more Second World War movies, as she played a married woman who has an affair with an American captain stationed in her northern English town in John Schlesinger's Yanks and the Norwegian who helps American Donald Sutherland blow up a U-boat base in Don Sharp's Alistair MacLean adaptation, Bear Island (both 1979).

Showing Her Character

Now in her forties, Redgrave remained a potent force on the West End stage. Either side of Evening Standard Award wins for The Lady From the Sea (1979) and The Seagull (1985), she won the Olivier Award for The Aspern Papers (1984). And it was another Henry James adaptation that saw her make something of a screen comback after she had been limited to a cameo as the Queen of England in Sergio Corbucci's Sing Sing (1983).

Scripted by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, produced by Ismail Merchant and directed by James Ivory, The Bostonians (1984) followed The Europeans (1978) in capturing the rarefied Jamesian milieu, as suffragist Olive Chancellor vows to prevent distant cousin Basil Ransom (Christopher Reeve) from marrying her protégée, Verena Tarrant (Madeleine Potter).

Redgrave earned Oscar and Golden Globe nominations for her performance in a film that established Merchant Ivory as the doyens of British heritage cinema. The team is profiled in Humphrey Dixon's documentary, The Wandering Company (1985), in which Redgrave also features. Around this time, she also provided Richard Burton with solid support as Cosima von Bülow in Tony Palmer's magnificent mini-series, Wagner (1983).

Having joined Sarah Miles and Diana Dors in the ensemble excelling in Joseph Losey's take on Nell Dunn's bath-house drama, Steaming, Redgrave shared the character of Jean Travers with her daughter, Joely, in David Hare's Wetherby (both 1985), a simmering saga that flashes back in time to explain a suicide in a spinster schoolteacher's Yorkshire cottage. The joint-winner of the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, this engrossing picture reunited Redgrave with classmate Judi Dench.

She followed it by playing New South Wales sheep farmer Violet Carlyle in Comrades, Bill Douglas's exceptional account of the pioneering Dorset trades unionists known as the Tolpuddle Martyrs. More controversy followed, however, as Redgrave played transgender tennis star Renee Richards in Anthony Page's teleplay, Second Serve (both 1986). But Redgrave was on irresistible form as Peggy Ramsay, the agent of gay playwright Joe Orton (Gary Oldman), in Stephen Frears's irreverent biopic, Prick Up Your Ears (1987).

Frustratingly, none of Redgrave's next nine outings is available on disc in this country, even though she teamed splendidly with sister Lynn in David Greene's tele-remake of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1991), in which they took roles of Blanche and Baby Jane Hudson that had been immortalised by Joan Crawford and Bette Davis in Robert Aldrich's 1962 adaptation of Henry Farrell's Grand Guignol novel. Vanessa also notably revisited a past project by playing Lady Alice More in Charlton Heston's tele-take on A Man For All Seasons and adopted a wayward Maltese accent as the vampish Mrs Garza in Giles Foster's grossly misfiring black comedy, Consuming Passions (1988). Also missing is Simon Callow's fine adaptation of Carson McCullers's The Ballad of the Sad Café (1991), in which Redgrave plays 1930s Georgia moonshiner, Miss Amelia. But Merchant Ivory were about to ride to the rescue once more.

Getting Her Wilcox in a Twist

According to James Ivory, Redgrave got the wrong end of the stick when he cast her in his latest E.M. Forster adaptation, Howards End (1992). She arrived on set believing she was to play Margaret Schlegel rather than Ruth Wilcox, the original owner of the eponymous country retreat rather than the kindly friend who inherits it and promptly marries the former man of the house. Nevertheless, Redgrave makes a touching contribution to the nine-time Oscar-nominated drama, although it must have nettled slightly that Emma Thompson won Best Actress at the Oscars (and the BAFTA) for a role that got away.

It's only natural in a career containing almost 150 credits that a fair few will go astray when it comes to home entertainment formats. But Redgrave has been unluckier than most in seeing 11 of the 24 features she made in the 1990s consigned beyond the reach of Cinema Paradiso. This is particularly sad in the case of Franco Zeffirelli's Sparrow (1993), John Irvin's A Month By the Lake (1995) and Bille August's Smilla's Sense of Snow (1997). But we still have several other titles to tempt you with.

For example, Redgrave, Meryl Streep and Winona Ryder play the matriarchal forebears of Sasha Hanau in Bille August's dense adaptation of Isabel Allende's Chilean saga, The House of the Spirits (1993). In James Gray's Little Odessa (1994), Redgrave steals scenes as the ailing mother of Tim Roth, a hitman for the Russian-Jewish mafia in Brooklyn. Then, in a delicious change of pace, she crops up as the grandmother who narrates the adventures of Toad (Rik Mayall), Rat (Michael Palin), Mole (Alan Bennett) and Badger (Michael Gambon) in Dave Unwin's animated retelling of Kenneth Grahame's beloved 1908 novel, The Wind in the Willows (1995).

Somewhat improbably, Redgrave next made her debut in a Hollywood blockbuster, as Max the arms dealer making life complicated for Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) in Brian De Palma's Mission: Impossible (1996). She would return to this heady atmosphere as journalist Téa Leoni's mother in Mimi Leder's colliding comet actioner, Deep Impact (1998). But she would spend the remainder of the decade in less apocalyptically combustible fare.

Brian Gilbert cast her as Stephen Fry's mother in Wilde (1997), a biopic of Irish dramatist Oscar Wilde that co-starred Jude Law as Lord Alfred Douglas. However, Dutch director Marleen Gorris gave her much more to do in the title role of Eileen Atkins's adaptation of Virginia Woolf's Mrs Dalloway (1997). Natascha McElhone plays the young Clarissa, as the politician's wife reflects on how her life has panned out while she prepares for a small party in 1920s London.

In making his directorial debut with Lulu on the Bridge, author Paul Auster cast Redgrave as Catherine Moore, a retired actress seeking to move behind the camera with a new version of Pandora's Box (Cinema Paradiso users can see Louise Brooks enchant in G.W. Pabst's 1929 silent version of Frank Wedekind's novel). Actor-turned-director Tim Robbins sought Redgrave to play Countess Constance LaGrange in Cradle Will Rock (both 1999), an account of how Orson Welles (Angus Macfadyen) found a way to mount a new musical by Marc Blitzstein (Hank Azaria) in New York at the height of the Great Depression.

And Redgrave closed the century as psychologist Sonia Wick in James Mangold's Girl, Interrupted (1999), a controversial reworking of Susanna Kaysen's memoir about her stay in a psychiatric hospital following a suicide attempt in the mid-1960s. Winona Ryder played Kaysen, but the plaudits went to Angelina Jolie, who won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her performance as sociopathic flight risk, Lisa Rowe.

Redgrave Regardless

Not long into the new millennium, Redgrave added to her collection of awards by winning a Golden Globe and an Emmy for her performance as Edith Tress, a lesbian mourning the loss of her longtime partner in Jane Anderson's '1961' segment of the HBO anthology, If These Walls Could Talk 2 (2000). She also contributed a sensitive lead as an ailing nursing home resident in Karen Arthur's TV-movie, The Locket (2002).

However, Redgrave was now primarily seen in supporting roles on screen, such as the grandmother of the child whose murder is being investigated by Nevada cop Jack Nicholson in Sean Penn's The Pledge; Countess Wilhemina, the great aunt of the giant-troubled hero of Brian Henson's Jack and the Beanstalk: The True Story (both 2001); and Clementine Churchill, opposite Albert Finney's as an out-of-office Winston, in Richard Loncraine's The Gathering Storm (2002).

She also voiced the Greater Dane from Dog Star Sirius 7 in John Hoffman's doggy sci-fi saga. Good Boy! (2003), and even got to play herself alongside Jane Birkin as an eccentric actress who believes she's Vanessa Redgrave in Andrew Litvack's Merci, Dr Rey (2002), which was produced under the Merchant Ivory banner. Furthermore, Redgrave reunited with James Ivory, alongside Lynn and Natasha, as three members of the exiled Belinskaya family in 1930s Shanghai in The White Countess (2005), which was scripted by novelist Kazuo Ishiguro.

Another clan connection led to Redgrave joining the cast of Nip/Tuck (2004-09), as Dr Erica Naughton, the mother of Julia McNamara, who was played by daughter Joely Richardson. Speaking of family ties, Vanessa also joined brother Corin in the Peace and Progress Party, which they launched in 2004 in response to the War on Terror. She only remained involved for a year, but continued to campaign for peace and human rights around the world.

Redgrave also remained a force in the theatre during a decade that saw her ranked as the ninth greatest stage performer of all time in a 2010 poll by the trade newspaper, The Stage. Having triumphed as Prospero in The Tempest at London's Globe Theatre in 2000, she won a Tony as Mary Cavan Tyrone in the 2003 Broadway revival of Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night. A Drama Desk Award and another Tony nomination followed for her one-woman turn as writer Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking (2007), while she earned rave reviews for two teamings with James Earl Jones, in Driving Miss Daisy (2010) and Much Ado About Nothing (2013).

Back on the screen, Redgrave remained as busy as ever. She played a bookbinder's heiress in Kayvan Mashayekh's Omar Khayyam biopic, Empire Rising (2005), before returning to holy orders as Sister Antonia in Richard Claus's adaptation of Cornelia Funke's bestseller, The Thief Lord. Then, having played painter's daughter Penelope Keeling in Piers Haggard's Rosamunde Pilcher mini-series, The Shell Seekers, she cameo'd as the Oscar-nominated Peter O'Toole's ex-wife, Valerie, in Venus (all 2006), Roger Michell's poignant dramedy about life, love and art.

In Brendan Foley's The Riddle, Redgrave essays a publisher eager to acquire a newly discovered Charles Dickens manuscript, while Lajos Koltai's Evening saw her play the dying mother of siblings Natasha Richardson and Toni Collette in a reflective adaptation of a Susan Minot novel that flashes back to the 1950s. The action spans six decades from the 1930s in Joe Wright's interpretation of Ian McEwan's Atonement (all 2007), in which Redgrave shares the role of writer Briony Tallis with the Oscar-nominated Saoirse Ronan and Romola Garai.

Rounding off the year, Redgrave joined forces with Imelda Staunton, Joss Ackland and Brenda Fricker to give residential home carer Hayley Atwell a tough time over Christmas in Anthony Byrne's How About You, which was based on a short story by Maeve Binchy. In 2009, Vanessa (playing another nun) and Joely came together for the BBC remake of John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids. But she was forced to withdraw from the role of Eleanor of Aquitaine in Ridley Scott's Robin Hood (2010) to console son-in-law Liam Neeson and her two grandchildren after Natasha died following a skiing accident in March 2009.

Indeed, this proved to be a desperately sad period in Redgrave's life, as she also lost Corin and Lynn on 6 April and 2 May 2010. But acting is in the Redgrave blood and she found solace in work. In Larysa Kondracki's The Whistleblower, she played Madeleine Rees, the head of the UN Human Rights Commission investigating sex trafficking in Bosnia, while she also guested as American philanthropist Bertha Spafford in Julian Schnabel's biopic, Miral (both 2010), which opens against the backdrop of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Always ready to do her bit for a good cause, Redgrave voiced Winnie the Giant Tortoise in Reinhard Kloos and Holger Tappe's animation, Animals United, which seeks to explain eco issues to younger viewers. She remained behind the microphone to narrate Patrick Keiller's semi-fictional documentary, Robinson in Ruins (both 2010), which completed a trilogy that had started with London (1994) and Robinson in Space (1997). Moreover, Redgrave also signed up to narrate the BBC favourite, Call the Midwife (2012-), as Jennifer Worth, on whose memoirs the series is based.

The call of the Bard proved impossible to resist, as Redgrave played the protagonist's mother, Volumnia, in directorial debutant Ralph Fiennes's version of Coriolanus. And Redgrave remained in period finery as Elizabeth I in Roland Emmerich's Anonymous (both 2011), which posits that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (Rhys Ifans) actually wrote the plays attributed to William Shakespeare. This chimes in with Redgrave's own long-held view that 'Whoever Shakespeare was, he wasn't a little ordinary yeoman who headed back to Stratford after he had his fun…I'm quite certain that he was a quite exceptional aristocrat who had to keep totally quiet and needed Shakespeare as cover.'

Returning to the present day, Redgrave appears briefly as the dying wife whose love of the local choir persuades grieving husband Terence Stamp to clear his throat in Paul Andrew Williams's Song For Marion. In essaying the title character, Redgrave lives on after death through the monologue that binds Rodrigo Gudiño's atmospheric horror, The Last Will and Testament of Rosalind Leigh (both 2012).

She's seen as another dying woman in James Kent's The Thirteenth Tale, as elusively reclusive novelist Vida Winter selects Margaret Lea (Olivia Coleman) to be her biographer. On a rare excursion to Hollywood, Redgrave appeared as Georgia plantation owner Annabeth Westfall in Lee Daniel's decade-hopping White House drama, The Butler (2013), and she remained Stateside to play the overbearing mother of wrestling enthusiast John Eleuthère du Pont (Steve Carell) in Bennett Miller's Oscar-nominated drama, Foxcatcher (2014).

Having played a scene that her father had enacted in Pete Travis's 2015 tele-remake of Joseph Losey's adaptation of L.P. Hartley's novel, The Go-Between (1971), Redgrave suffered a near-fatal heart attack in April 2015. Most people would slow down after such an alarm call. But the 80 year-old decided to make her directorial bow with Sea Sorrow (2017), a documentary about the European migrant crisis that cast Ralph Fiennes as Prospero and Emma Thompson as Sylvia Pankhurst. It's a shame that no one has thought to release this timely treatise on disc in the UK.

The same is true of Georgetown (2018), Christoph Waltz's first feature as a director, in which Redgrave plays an author who falls for a social climber. However, Cinema Paradiso users can see her as Jeanne McDougall, the mother of Hollywood actress Gloria Grahame (Annette Bening) in Paul McGuigan's Film Stars Don't Die in Liverpool (2017), and as the demanding mother of artist L.S. Lowry (Timothy Spall) in Adrian Noble's Mrs Lowry & Son (2019).

Dame Vanessa is one of the select group of 24 performers to have achieved the Triple Crown of Oscar, Tony and Emmy. Surely someone can find her a spoken word assignment so she can add a Grammy and join the 16-strong EGOT club? But she remains busy, whether appearing in TV shows like Man in an Orange Shirt (2017) and Worzel Gummidge (2020), or co-starring with daughter Joely in Livia De Paolis's Peter Pan-themed drama, The Lost Girls, which is due for release later this year. And don't think she's stopped protesting, either!