For decades, French films branded 'Tradition of Quality' were regarded as stuffy and old-fashioned. But do they really deserve to be condemned to the cinematic dustbin? Cinema Paradiso investigates.

Seventy years have passed since François Truffaut wrote an article in Cahiers du cinéma denouncing what he called a 'certain tendency' in French film. His ideas on auteur cinema helped spark the nouvelle vague that transformed how films were made and critiqued for decades. But the 'Tradition of Quality' that Truffaut derided had its saving graces.

Silent Beginnings

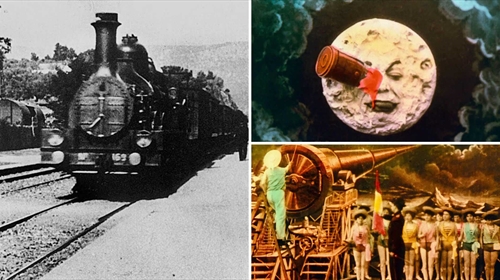

As Cinema Paradiso users will know, the first motion pictures were projected to a paying audience on 28 December 1895 in Paris. As films like John Boulting's The Magic Box (1951) and Wim Wenders's A Trick of the Light (1995) reveal, attempts were made to create moving images before Auguste and Louis Lumière cast Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon (1894) into the Salon Indien darkness. Thirteen of their one-reelers can be found on the BFI's marvellous Early Cinema: Primitives and Pioneers (1895-1910) selection, along with Voyage à travers l'impossible (1904), which was directed by the peerless Georges Méliès.

While Lumière agents were taking their methods and equipment to every corner of the globe, the 'Magician of Montreuil' was transporting viewers to other worlds in mini-epics like A Trip to the Moon (1902). Méliès made between 600-800 titles for Star Films before going bankrupt in 1914. His career is recalled in Jacques Meny's Méliès the Magician (1997), while his old age is romanticised in Martin Scorsese's charming fantasy, Hugo (2011).

The BFI collection also includes nine films by Pathé Frères, including Peeping Tom (1901) and Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves (1902). This was the year Charles and Émile Pathé adopted the Gallic rooster as their emblem and it's still in use today. In 1907, the company pioneered the tripartite system of production, distribution, and exhibition that proved to be the basis of the Hollywood studio system, while Pathé also encouraged members of the Académie française and Comédie française to adapt novels and plays to entice the middle-classes into cinemas and these films d'art helped legitimise the medium in the early days of feature production and laid the foundations for the so-called 'Tradition of Quality'.

Several rival companies grew up, the most enduring being founded by Léon Gaumont, whose assistant became a major force in establishing a film industry on America's Eastern seaboard. Her achievement is celebrated in Pamela B. Green's Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché (2018). But, as the BFI's Early Women Film-makers 1911-1940 (2019) shows, she was not the only French female pioneer, with

Germaine Dulac ( La Cigarette, 1919) and Marie-Louise Iribe ( Le Roi des Aulnes, 1931) also making notable contributions.

Among the other icons of French silent cinema is Max Linder, whose slapstick style had an incalculable influence on Charlie Chaplin. He can be seen in All Good Fun (1955), a compilation that forms part of The Renown Comedy Collection, Volume 1 (2016). Also check out the delights from the dawn of cinema contained within the six volumes of the wonderful Lobster Film series, Retour de Flamme. On a grander scale, Louis Feuillade's serials, Fantômas (1913) and Les Vampires (1915), teased out their stories over several episodes and established the tropes of the crime and thriller genres in the process. Indeed, Musidora's famous character in the latter would be revived by Maggie Cheung in Olivier Assayas's Irma Vep (1996).

Already facing competition from Scandinavia and the United States, France lost its position as the centre of the film world during the Great War, when production halted for several months before the government recognised the value of screen propaganda. Hollywood protectionism and the rise of UFA in Germany exposed the frailties of the French film industry, which was comprised of small independent companies rather than powerful studios. Moreover, film-making techniques had progressed and an adherence to photo-realism had left French cinema looking antiquated.

Critic Louis Delluc called for films to be more French and more visually innovative. The style he championed has become known as Impressionism, with his own final film, The Flood (1924), being linked in the loose movement with Germaine Dulac's La Souriante Madame Beudet (1922), Jean Epstein's Coeur fidèle (1923), Abel Gance's Napoléon (1927), Marcel L'Herbier's L'Argent, and Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (both 1928).

The latter was made by a Dane who had also made Michael (1924) in Germany. Russian exiles Dimitri Kirsanoff, Yakov Protozanov, Victor Tourjansky, and Alexander Volkov also took up residence in Montreuil. But it was a pair of Spaniards who shocked the French cine-establishment in 1929, with the Surrealist imagery in Un chien andalou. However, Luis Buñuel made L'Áge d'or (1930) without Salvador Dalí, although their friendship did later inspire Paul Morrison's Little Ashes (2008).

On the periphery of this avant-garde group were American photographer Man Ray (Return to Reason, 1923), artists Fernand Léger (Ballet mécanique, 1924) and Marcel Duchamp (Anaemic Cinema, 1926), film-maker René Clair (Entr'acte, 1924), and Brazilian maverick Alberto Cavalcanti (Rien que les heures, 1926). As Cinema Paradiso users can discover by tapping his name into the searchline, the latter would go on to play a key role in British cinema in the 1940s. We shall shortly see how Clair would be lured to Hollywood. But much mainstream French cinema from the postwar silent era has been forgotten. Hence, even works by such once prominent directors as Jean Kemm and René Leprince are unavailable on disc on this side of the Channel.

Poetic Realism and Wartime Reality

As we saw in the Cinema Paradiso article, A Brief History of French Poetic Realism, the coming of talking pictures increased the reliance of French film-makers on literary and theatrical texts. As talkies were so expensive to make, producers felt it reduced the risk to base features on pre-existing material. Consequently, playwrights such as Molière, Jean Racine, Pierre Corneille, Pierre Beaumarchais, and Georges Feydeau and novelists like Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac, Gustav Flaubert, Alexandre Dumas (père and fils), and Émile Zola became cinematic standbys and rooted French film in what François Truffaut would scathingly call, the 'Tradition of Quality'.

Modern writers like Mac Orlan, Eugène Dabit, and the Belgian duo of Georges Simenon and Stanislas-André Steeman brought a grittier social realism to novels and their influence can be felt in the Poetic Realist style that emerged in the mid-1930s as a reaction against the adaptations that focussed more on the text than the imagery. Among the key directors referenced in the aforementioned Brief History are Jean Vigo ( L'Atalante, 1934), Jacques Feyder ( Le Grand jeu, 1934), Jean Renoir ( Le Crime de Monsieur Lange, 1935), Julien Duvivier ( Pépé le Moko, 1937), and Marcel Carné ( Quai des brumes, 1938). We also have an Instant Expert's Guide to Renoir if you want to see how this phase fits into his overall career.

Defiantly remaining outside the cinematic mainstream, Marcel Pagnol and Sacha Guitry went their own way during the 1930s and it's scandalous that so few of their works are available on disc in this country outside the Guitry double bills of The New Testament and My Father Was Right (both 1936) and Let's Make a Dream (1936) and Let's Go to the Champs-Elysées (1938). The later comedy, Poison (1951), is also available, as are Raymond Bernard's Wooden Crosses (1932) and Abel Gance's I Accuse (1938), which each reflect on the legacy of the Great War. And there are lots of Pagnol adaptations made in the heritage style by Claude Berri, Yves Robert, and Daniel Auteuil. Again, see the Poetic Realism article or use the searchline for details.

With the diplomatic situation in Europe deteriorating, several Jewish film-makers left Germany for Hollywood. Some lingered in the Third Republic before crossing the Atlantic, with their experience of 1920s Expressionism (see 100 Years of German Expressionism ) shading the increasingly pessimistic pictures of late Poetic Realist period. But it was to be the Nazis in control of Continental Films during the Occupation that would have a more lasting effect on French cinema, as the likes of Clair, Duvivier, Renoir, Max Ophüls, and Anatole Litvak all plied their trade in Hollywood, along with stars like Simone Simon, Michèle Morgan, and Jean Gabin.

Film-making continued up to the invasion of France in the spring of 1940. Once the Vichy regime had been established, however, the film industry was restructured under the Comité d'Organisation des Industries du Cinéma, which not only banned Jews and Communists from working, but also established a funding system that stabilised and boosted production. The COIC also set up the Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques under Marcel L'Herbier in 1944. Dozens of celebrated directors trained at the IDHEC film school (which now operates as La Fémis), including Louis Malle, Alain Resnais, Claude Sautet, Costa Gavras, Volker Schlöndorff, Theo Angelopoulos, Jesús Franco, Claude Miller, Andrzej Zulawski, Jean-Jacques Annaud, Claire Denis, Patrice Leconte, Rithy Panh, and Arnaud Desplechin. Type their names into the Cinema Paradiso searchline to gauge their achievements.

While COIC ensured that French film was well funded, it imposed a code of censorship that stifled creativity. Oxford-educated novelist Paul Morand was placed in charge of the commission and found himself in the invidious position of banning a film he had actually scripted, Jean Epstein's La Glace à trois faces (1927), as it was considered morally dubious.

As Bertrand Tavernier reveals in Laissez-passer (aka Safe Conduct, 2002), film-making was controlled by Continental Films, which oversaw the production of 220 features. Research suggests that while scripts embraced such themes as submission to authority, respect for the patriarchy, duty, moral decency, and a love of the land, overt propaganda was rare in the various comedies, dramas, musicals, thrillers, and fantasies that were sanctioned. Period pictures proved a particularly effective way of providing escapism, while avoiding potentially provocative contemporary issues. In the absence of Hollywood pictures, attendances rose, although audiences often barracked agitprop passages and stayed away from German and Italian imports.

Rather than work for Continental, a number of directors, actors, and technicians moved to the Free Zone, although some remained to sabotage shoots and shelter Jewish artists with forged papers by finding them work. Others joined Jean-Paul Le Chanois, Louis Daquin, Pierre Renoir, Jean Grémillon, and Jacques Becker in the Comité de Libération du Cinéma Français, which not only filmed the Maquis in action, but also served as a network for circulating screenplays and the magazine, L'Ecran français. In 1944, the CLCF was also behind the short, Journal de la résistance: la Libération de Paris, which chronicled the German retreat. But the film that most definitively confirmed that the war was over was Marcel Carné's Les Enfants du paradis (1945), a paean to the French spirit that had been made under the noses of the Nazis and delayed so that it would be shown in a free country.

Truffaut's Tirade

Such was the state of the French film industry at the end of the war that the newly formed Centre National du Cinéma (CNC) decided to leave in place the Vichy structures that had provided such stability. Funding came from a tax on tickets, while a deal was struck within the Blum-Byrnes trade agreement with the United States that cinemas would be obligated for five weeks each year to show French films only in order to offset the impact of the Hollywood backlog.

In 1949, a co-production pact was struck with Italy and the need to produce pictures that appealed to audiences in both countries prompted a conservative approach to subject matter and techniques. In a bid to reduce the risk of films failing at the box office, it was decided to place an emphasis on name recognition, which meant a reliance on familiar faces in stories by well-known authors. The identity of the director mattered less, as their job was to tell the tale effectively and ensure that the stars, costumes, and sets (particularly in period pictures) looked good. Moreover, with unions protecting film crews and censorship still being rigorously enforced, with the country at war in Indochina and Algeria amidst tensions with the Soviet bloc, directors (who had often served lengthy apprenticeships and become accustomed to the stylistic status quo) had little scope for visual creativity.

This situation infuriated François Truffaut, a young critic on Cahiers du cinéma, a journal that had been launched by the influential film theorist, André Bazin. Cinema Paradiso members can learn about Truffaut's troubled background in our Instant Expert's Guide. But, even though he was known as a passionate writer with distinctive views on what audiences had a right to expect from their film-makers, few were prepared for the fallout when an article entitled, 'Une certaine tendance de cinéma français' appeared in Issue No.31 in January 1954.

The piece was sparked by Bazin's thoughts on Robert Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest (1951), in which he had claimed that the brilliance of the adaptation of Georges Bernanos's novel made celebrated screenwriters Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost look like the cine-equivalent of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, an architect whose reputation rested on his restoration of Paris's medieval landmarks. Truffaut lamented that such films were rare and grumbled that, of the 100 or so features made in France each year, only around a dozen 'merit the attention of critics and cinephiles'.

The trouble was, these pictures belonged to what fellow critic Jean-Pierre Barrot had admiringly called in L'Ecran Français, a 'Tradition of Quality', as they won prizes at Cannes and Venice and drew enthusiastic reviews in the foreign press. Truffaut disliked these films, however, and joked that it was apt that Billancourt Studio was next to a cemetery, as most of its output was dead on arrival. He criticised them for replacing the poetic realism he revered with 'réalisme psychologique', which placed greater emphasis on story, theme, and setting than visual imagination. Punning on the title of Marcel Carné's Les Portes de la nuit (1946), he despaired that screenwriter Jacques Prévert (who had penned numerous prewar classics) had slammed the door on creative directing and left the field to the likes of Claude Autant-Lara, Jean Delannoy, René Clément, Yves Allégret, Marcello Pagliero, Ralph Habib, André Cayatte, Yves Ciampi, and Gilles Grangier, whom he considered mere script illustrators or metteurs-en-scène.

Citing examples of their commercial hits, Truffaut accused these directors of playing second fiddle to their writers on the likes of Delannoy's La Symphonie pastorale (1946), Autant-Lara's Le Diable au corps (1947), Allégret's Manèges (1949), Pagliero's Un homme marche dans la ville (1950), and Clément's Jeux interdits (1952). The very fact that only one of these titles is currently on disc in the UK reveals the extent to which Truffaut's thesis and concepts like 'cinéma de papa' and 'les politiques des auteurs' have shaped the way in which French screen history has subsequently been written.

In targeting his ire at Aurenche and Bost, Truffaut sneered at the diverse nature of the novels they choose to adapt and the differing personalities of the directors with whom they most regularly collaborated. He also castigated them for promoting anti-clerical, anti-militarist, and anti-bourgeois sentiments and peddling smut, profanity, and pessimism under the guise of moral conformism, while also cheating producers and viewers alike by changing the source material without making it any more cinematic. 'The sun rises and sets like clockwork,' he wrote, 'characters disappear, others are invented, the script deviates little by little from the original and becomes a whole, formless but brilliant: a new film, step by step makes its solemn entrance into the "Tradition of Quality."'

The phrase Truffaut actually uses is 'la qualité française', which is all the more damning, as it suggests that the entire French film industry is failing to provide viewers with visual innovation or identity. He points the finger at Jacques Sigurd, Jean Ferry, Robert Scipion, Roland Laudenbach, André Tabet, Jean Guitton, Pierre Verys, Jacques Companeez, and Jean Laviron, as well as such prewar scenarists as Charles Spaak and Georgy Natanson, who had betrayed their poetic instincts. Few of these names will mean much to non-specialists and there's little point listing the films to which Truffaut refers, as none of them are available to rent - even though the majority are expertly made and highly entertaining. Such is the impact of Truffaut's article that they have been virtually airbrushed out of English-language histories of French cinema and that is an enormous shame.

Rather than simply discrediting, however, Truffaut also highlighted a number of 'cineastes whose worldview is at least as valuable as that of Aurenche and Bost, Sigurd and Jeanson. I mean Jean Renoir; Robert Bresson, Jean Cocteau, Jacques Becker, Abel Gance, Max Ophüls, Jacques Tati, Roger Leenhardt; these are, nevertheless, French cineastes and it happens - curious coincidence - that they are auteurs who often write their dialogue and some of them themselves invent the stories they direct.'

In due course, Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, Jerry Lewis, Robert Aldrich, Nicholas Ray, Fritz Lang, Roberto Rossellini, and Kenji Mizoguchi would be among those added to this pantheon of auteurs. They would be joined during the nouvelle vague by Truffaut himself, as well as such Cahiers colleagues as Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Éric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette, along with such Left Bank film-makers as Alain Resnais, Louis Malle, Chris Marker, Agnès Varda, and Jacques Demy.

Such was the impact of this New Wave on film production in Hollywood and beyond that a sizeable proportion of critics and scholars in the 1960s went along with what Andrew Sarris called 'auteur theory'. Their students continued to enshrine the notion that directors should be regarded as the driving creative force on a film by using the camera as authors wield a pen in order to project their own personalities and preoccupations. It's only in recent times that auteurship has been challenged for diminishing the contributions of other key creatives and for privileging the status of predominantly white male directors. So how does the rest of Truffaut's argument stand up 70 years on?

Never Mind the Quality

By accepting Truffaut's verdict that the qualité française was smothering domestic cinema, there's a risk of dismissing a decade's worth of perfectly good films that had been enjoyed by the audiences of the day. French film might have become a little stagnant, but it most certainly wasn't in crisis. Indeed, the combination of organisational and legislative measures, technical advancement, and an acknowledgement of popular tastes not only enabled the French film industry to recover from the devastation of the war, but also cope with the competition posed by Hollywood films and the spread of television in order to provide a stable basis that held firm into the 1980s.

Even in the Poetic Realist era, producers tended to hire writers to pen treatments, scenarios, and dialogue before they chose a director or the technicians and the cast. This packaging process actually afforded more creative latitude than the Hollywood studio system. Moreover, it could be argued that the 'tendency' was a conscious attempt to differentiate domestic from imported products by concentrating on the aspects that made the films distinctively French - narrative, dialogue, star performance, cinematography, set design, and costume. Similarly, film-makers used historical reconstructions and adaptations of classic literary texts to circumvent censorship restrictions and comment on pressing contemporary issues.

There's no denying that French cinema had settled into the pattern that Truffaut railed against. The fact is, audiences of the time didn't seem to mind. In her excellent 2015 article, 'Screenwriters in Post-war French Cinema', Sarah Leahy shows how successful so many Tradition of Quality pictures were at the box office. She also notes how the popular genres that never get mentioned in film histories - like comedy, the musical, melodrama, and the thriller - also performed well. Admittedly, films by Truffaut's first draft of auteurs also featured on the end of year charts. But the commercial facts demonstrate that Truffaut was in a minority in wanting to tear down the French cinematic edifice and start all over again.

As we shall see, many of the writers and directors he ridiculed remained busy after the nouvelle vague had come and gone. Moreover, only a handful of those who made their directorial debuts between 1959-63 went on to enjoy long careers. Thus, while Truffaut's article ruffled feathers and prompted him and his fellow Jeunes Turcs to produce their own films, it didn't shake the establishment to its foundations. Indeed, if anything, 'Une certaine tendance de cinéma français' exposed Truffaut's own socio-politicial conservatism, petty prejudices, and youthful arrogance. But it also exhibited passion, positivity, and purpose, and these attributes would serve him well when he embarked upon his own directorial odyssey.

50s French Playlist

So, you are no doubt thinking, enough of the history lesson. What can we watch? As mentioned above, far too many of the features made in France in the 1950s are unavailable on disc - on either side of La Manche. But, with 100,000 titles in its unique library, Cinema Paradiso can offer more of the masterpieces and overlooked gems than anyone else. And we can recommend the ultimate starting point for any voyage of discovery: Bertrand Tavernier's Journey Through French Cinema (2018).

Without trying to be auteurist about things, it's easier to discuss films by director than screenwriter. Nevertheless, we'll try to give credit where it's due. We'll start with those whose careers straddled the war and, thus worked in the poetic and psychological realist eras.

First up is René Clair, who started out in the silent twenties before being among the first to make creative use of sound in classics like À nous la liberté (1931). While in Hollywood, Clair demonstrated his versatility with The Ghost Goes West (1935), The Flame of New Orleans (1941), I Married a Witch (1942), Forever and a Day (1943), It Happened Tomorrow (1944), and And Then There Were None (1945). Sadly, the only title available from his second French phase is Les Grandes manoeuvres (1955), but he did enough with Le Silence est d'or (1947) and the Franco-Italian fantasies, La Beauté du diable (1950) and Les Belles de nuit (1952), to fall foul of Truffaut.

He got off lightly, however, compared to Claude Autant-Lara. Curiously, Cinema Paradiso's first encounter with him is the prewar British thriller, The Mysterious Mr Davis (1939), which is paired with Henry Edwards's The Lad (1935). He worked with Aurenche and Bost on Le Diable au corps (1947), Le Rouge et le noir (1954), La Traversée de Paris (1956), and En cas de malheur (1958), all of which are solidly crafted, but out of rental reach. We can, however, bring you the popular comedian Fernandel in L'Auberge rouge (1951), which joins a group of travellers in a remote mountain inn.

Even more off limits is Aurenche and Bost's other most frequent collaborator, Jean Delannoy. It's a particular shame we can't offer the wartime classic L'Eternal retour (1943) or the sublime André Gide adaptation, La Symphonie pastorale (1946). But there's also much to commend Les Jeux sont faits (1947), from an original screenplay by Jean-Paul Sartre, and the Aurenche and Bost-scripted Dieu a besoin des hommes (1950), Chiens perdus sans collier (1955), and Notre-Dame de Paris (1956), which starred Anthony Quinn and Gina Lollobrigida and was co-written by Aurenche with Jacques Prévert.

The latter was noted for his 1930s collaborations with Marcel Carné. But his only postwar film currently on disc is Paul Grimault's animation, The King and the Mockingbird (1980), as Carné paired with Charles Spaak on Thérèse Raquin (1953) and Jacques Sigurd on L'Air de Paris (1954), which reunited the fabled pairing of Jean Gabin and Arletty from Le Jour se lève (1939). Another to fade after the war was Jean Grémillon, who had impressed with Remorques (1941), Lumière d'été (1943), and Le Ciel est à vous (1944). All that is currently available to rent, however, is the compelling drama, The Love of a Woman (1953).

Aurenche and Bost also wrote Jeux interdits for René Clément. He had helped Jean Cocteau with La Belle et la bête before making the influential Maquis saga, La Bataille du rails (both 1946). Neither Les Maudits (1947) nor Au-delà des grilles (1949) is currently available, but Cinema Paradiso users can enjoy the Tradition of Quality classic, Gervaise (1957), as well as the pictures that proved there was life after being mauled by Truffaut: Purple Noon (1960), Is Paris Burning? (1966), Rider on the Rain (1969), The Deadly Trap (1971), and And Hope to Die (1972).

Another to flourish after being cited by Truffaut was Henri-Georges Clouzot. Nicknamed 'the French Hitchcock', he had made his name during the Continental interlude with The Murderer Lives At 21 (1942) and Le Corbeau (1943), a thriller about poison pen letters that annoyed collaborators and resisters alike. Overturning a postwar lifetime ban, Clouzot made the noirish police procedural, Quai des Orfèvres (1947), and an adaptation of Abbé Prévost's Manon (1948), which he co-wrote with Jean Ferry, who was on Truffaut's qualité française list.

No one can doubt the quality, however, of The Wages of Fear (1953) and Les Diaboliques (1955), which redefined the action adventure and the Grand Guignol chiller. Indeed, Alfred Hitchcock even paid homage to the latter in Psycho (1960). Having shown himself to be a dab hand at experimental documentary with The Mystery of Picasso (1956), Clouzot produced an espionage caper ( Les Espions, 1957), a courtroom whodunit ( La Vérité, 1960), and a psychological thriller ( La Prisonnière, 1968). Fate conspired to prevent him completing a brooding 1964 drama starring Romy Schneider and Serge Reggiani, but Cinema Paradiso users can discover why the project foundered in Serge Bromberg's haunting documentary, Inferno (2009).

Among the many dependable directors to have slipped through the net because of the critical backlash against 1950s French cinema are Jean Stelli, André Hunebelle, Henri Calef, Henri Diament-Berger, Jean Dréville, Léo Joannon, Jean-Paul Le Chanois, Léonide Moguy, Richard Pottier, Marc-Gilbert Sauvajon, and Christian-Jaque. The latter should be much better known, as he made swashbuckling masterclasses like the Gérard Philipe vehicle, Fanfan la Tulipe (1952), as well as those acme Tradition of Quality titles, Lucrèce Borgia (1953) and Nana (1955), with the inimitable Martine Carol, who headlined Max Ophüls's Lola Montès (1955).

Ophüls was one of the chosen few and Cinema Paradiso regulars can discover why by renting La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1951), and Madame de... (1953). During his sojourn in Hollywood, Ophüls directed Letter From an Unknown Woman, Caught (both 1948), and The Reckless Moment (1949). Jean Renoir was in California at the same time, where he made Swamp Water (1941), The Amazing Mrs Holliday (1943), The Southerner (1945), and The Woman on the Beach (1947) before heading to India to adapt Rumer Godden's The River (1951).

Returning to France after an extended absence, Renoir divided audiences and critics with his theatrical spectacle trilogy of The Golden Coach (1951), French Cancan (1954), and Eléna et les hommes (1956). Already a Cahiers icon, Renoir finished the decade with the underrated duo of Le Testament du docteur Cordelier and Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (both 1959). The contrast with their predecessors is fascinating and we do urge you to watch.

While Anatole Litvak remained in Hollywood - where he had remade Le Jour se lève as The Long Night (1947) and guided Ingrid Bergman to the Best Actress Oscar in Anastasia (1956) - Julien Duvivier returned home after directing such delights as Tales of Manhattan (1942). Known for pre-war classics like Un Carnet de bal and Pépé le Moko (both 1937), he made Panique (1946) in Paris and Anna Karenina (1948) in London before finding found himself in Truffaut's sights, despite the success of his teaming with Fernandel in a much-loved adaptation of Giovanni Guareschi's The Little World of Don Camillo (1952).

Before we move on to the trendier 1950s directors, we should mention some of the other 200 or so screenwriters who kept French cinema going during this period. Among those to note are Jean Boyer, Jean Manse, Henri Jeanson, Michel Audiard, Paul Vandenberghe, Serge Véber, René Barjavel, Gérard Carlier, Jean-Pierre Feydeau, Jean Halain, André Tabet, Maurice Griffe, and Albert Simonin. But, as Sarah Leahy points out, there were few opportunities for women scenarists in this male-dominated industry. So, we proudly salute Jacqueline Boisyvon, Arlette de Pitray, Louise de Vilmorin, Françoise Giroud, Elisabeth Montagu, Annette Wademant, and Colette Audry, whose sister Jacqueline was one of the few female French directors at this time and who made a splendid job of Gigi (1949), Olivia (1951), and Huis-clos (1954).

Cinema was only one strand to Jean Cocteau's bow. But, in addition to directing The Blood of a Poet (1932), Orphée (1950), and Testament of Orpheus (1959), he also hired Jean-Pierre Melville to adapt Les Enfants terribles (1950). Adopting his surname from the author of Moby Dick (filmed by John Huston in 1956), Melville had made his reputation with the wartime romance, The Silence of the Sea (1949), and he would return to the Occupation in Léon Morin, Priest (1961) and Army of Shadows (1969). But he specialised in crime pictures with a hard edge, with Bob le flambeur (1956) being a noir classic. Following Le Doulos (1963), with Jean-Paul Belmondo, Melville teamed with Alain Delon on the exceptional trio of Le Samouraï (1967), Le Cercle rouge (1970), and Un flic (1972).

Every bit a hero of the nouvelle vague as Melville was Jacques Becker. He was one of the directors to get a start during the war, with Falbalas (1945) starring Micheline Presle, who passed away after over 150 films on 21 February 2024 at the age of 101. Becker could make comedies like Edward and Caroline (1951), period pieces like Casque d'or (1952) and Montparnasse 19 (1958), and such noirish crime dramas Touchez pas au grisbi (1954) and Le Trou (1960). As he proved with A Man Escaped (1956) and Pickpocket (1959), Robert Bresson could also make rivetting crime pictures. But, while he started with relatively conventional dramas like Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945), he developed a distinctive minimalist style with The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962), Au hasard Balthazar (1966), Mouchette (1967), Lancelot du lac (1974), The Devil, Probably (1977), and L'Argent (1983) that made him one of the most admired directors of his day.

A former music-hall performer, Jacques Tati also refined a style that was all his own. He is unique among his peers for acting in his own films, notably playing François the eager postman in Jour de fête (1949) and the angular and accident-prone Monsieur Hulot in Monsieur Hulot's Holiday (1953), Mon oncle (1958), Playtime (1967), Trafic (1971), and Parade (1974). And don't forget to check out Sylvain Chomet's The Illusionist (2010), which was based on an unrealised Tati script, and the gems in The Short Films By Jacques Tati (2014).

Like Tati, Bresson, Becker, and Melville, Georges Franju wasn't associated with either the Tradition of Quality or the New Wave. But his influence on the emerging auteurs was readily evident. Cinema Paradiso users are in for a treat (although sometimes a discomfiting one) if they order Head Against the Wall (1959), Eyes Without a Face (1960), Spotlight on a Murderer (1961), Judex (1963), and Noces rouges (1973). Another non-aligned director was Roger Vadim, who made a star of Brigitte Bardot in And God Created Woman (1956), The Night Heaven Fell (1958), and Love on a Pillow (1962). He also married Jane Fonda, whom he starred in the 'Metzengerstein' segment of Spirits of the Dead and Barbarella (both 1968). However, he proved to be something of an erratic maverick and few of his later films, including a reunion with Bardot on Don Juan (1973), were praised and he wound up remaking And God Created Woman (1988), with Rebecca De Mornay.

By the end of the decade, some of the leading lights in the nouvelle vague had made their first films. Among the most enduring are Agnès Varda's La Pointe courte (1954), Claude Chabrol's Le Beau Serge (1958), Les Cousins, and À double tour (both 1959), and Éric Rohmer's The Sign of Leo (1962), which can be found on The Early Works of Éric Rohmer. Louis Malle also added Les Amants (1958) and Lift to the Scaffold (1959) to The Silent World (1956), an Oscar-winning documentary that he had co-directed with underwater explorer, Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

Having also started out with actualities like the devastating Holocaust memorial, Night and Fog (1956), Alain Resnais also moved into features with Hiroshima mon amour (1959). But the film released that year that turned world cinema on its head was François Truffaut's Les 400 coups, although that's a story for another time. André Tabet, Jean Guitton, Pierre Verys, Jacques Companeez, and Jean Laviron.