There have been several family dynasties in Hollywood history, with the Selznicks, Barrymores, Carradines, Hustons, Fondas and Coppolas most readily coming to mind. The British Isles, of course, have the Chaplins, Redgraves, Cusacks and Foxes. But this country can also boast an extended family of film-makers that forms a creative link from the silent era to the present day. Let Cinema Paradiso introduce them.

The names of some of the people we are about to profile may not be all that familiar. But the films they've produced have been delighting audiences for almost a century. Along the way, we shall encounter uncles, nephews, brothers, sisters, husbands, wives, fathers and sons. There are also some enduring partnerships and the odd lingering feud. So, let's meet the family.

Uncle Vic

Victor Saville was born Victor Salberg in Birmingham on 5 September 1897 into an Orthodox Jewish family that had fled Poland during the previous decade. His father wanted him to study law, but he volunteered to fight in the Great War and was invalided out of the London Irish Rifles after receiving a head wound during the Battle of Loos in 1915.

On returning to Civvy Street, Salberg formed Victory Motion Pictures with his boyhood friend, Michael Balcon, and began renting and importing films before he started directing commercials around the time he changed his name to Saville on the advice of his new wife, Phoebe, whose uncle was C.M. Woolf, whose W & F Film Service had made a fortune immediately after the war by importing French and German films and inserting translated intertitles. Woolf helped Saville and Balcon set up Gainsborough Pictures, which scored its first major success with Alfred Hitchcock's The Lodger (1927).

Saville established ties with the Gaumont Company and made his directorial debut with The Arcadians (1927). However, it took the coming of sound for him to find his voice after Balcon had become production chief at the Gaumont-British Picture Corporation. He scored his first hit with I Was a Spy (1933), which starred Madeleine Carroll in a biopic of Belgian nurse Marthe Crockaert, who had saved Allied and German alike on the Western Front. But Saville made his name through a partnership with the versatile Jessie Matthews in a string of musicals and comedies.

Having teamed with John Gielgud and Edmund Gwenn in an adaptation of J.B. Priestley's The Good Companions, Matthews demonstrated her dramatic talent in Friday the Thirteenth (both 1933) and her gift for song and dance in Evergreen (1934), First a Girl (1935) and It's Love Again (1936). She also worked with Hitchcock on Waltzes From Vienna (1933) before making a clutch of pictures with her husband, Sonnie Hale. These are all available to rent from Cinema Paradiso on the six volumes of The Jessie Matthews Revue.

While items like the Cicely Courtneidge vehicle, Marlborough and Me (1935) - which can be found on British Comedies of the 1930s: Vol.8 - showed he had the light touch, Saville was also keen to prove he could handle weightier fare and directed George Arliss as the Duke of Wellington in The Iron Duke (1934). He ventured back into the 18th century to star Clive Brook and Madeleine Carroll as King Christian VII of Denmark and his English consort, Caroline Matilda, in The Dictator (1935), which is available to rent on The Ealing Studios Rarities Collection: Vol.13.

The following year, he struck out as an independent by basing Victor Saville Productions at Alexander Korda's Denham Studios, where he did much to raise the profile of Vivien Leigh, alongside Conrad Veidt in Dark Journey and Rex Harrison in Storm in a Teacup (both 1937). However, Saville was unable to resist the chance to replace Balcon as production chief at MGM's Borehamwood Studios, where he helped steer Robert Donat towards the Academy Award for Best Actor in Sam Wood's Goodbye Mr Chips (1939).

Happier producing than directing, Saville relocated to Hollywood and so infuriated Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels with Frank Borzage's The Mortal Storm (1940) that all MGM films were banned from the Third Reich. Saville relished dealing with stars like Ingrid Bergman, Spencer Tracy, Katharine Hepburn and Joan Crawford in overseeing Victor Fleming's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1941), George Cukor's Keeper of the Flame (1942) and Richard Thorpe's Above Suspicion (1943). But he also made a reluctant return behind the camera for his short contribution to the wartime flag-waver, Forever and a Day (1943), and accepted Columbia's offer to direct Rita Hayworth in Tonight and Every Night (1945), a frothy tale about London's Theatreland during the Second World War.

However, Saville never quite returned to form after the car crash death of his son, despite getting to direct Errol Flynn in an adaptation of Rudyard Kipling's Kim (1950) and a debuting Paul Newman in the Early Christian saga, The Silver Chalice (1954). He hoped to make a quick buck by acquiring the rights to Mickey Spillane's Mike Hammer novels. But, while Robert Aldrich's Kiss Me Deadly (1955) became a cult classic, Saville had more problems adapting My Gun Is Quick (1957), which he partially directed with George White under the alias Phil Victor. On returning to Britain, he had more luck producing Lewis Gilbert's version of Rumer Godden's The Greengage Summer (1961) but decided to call it a day and lived in golfing retirement until 8 May 1979. We shall return presently to the careers of his uncle-in-law and his director nephews.

Boxing Clever

The next branch in our family tree had roots in Beckenham in Kent and New Malden in Surrey. Eight years older than his sister, Betty (more of whom anon), Sydney Box was born on 29 April 1907 to an army quartermaster and his wife. She encouraged her 11 year-old son to pen a one-act play for a local arts festival and he continued to write for the stage after becoming a cub reporter at the age of 13. Sydney's first marriage collapsed in 1932, following an affair with Muriel Baker, who had been born in Surrey on 22 September 1905 and had harboured ambitions of becoming an actress before winding up as a typist at British Instructional Films, where Mary Field had become a pioneering woman director with her Secrets of Nature series.

Having moved to Elstree, Muriel worked as a personal assistant to both Anthony Asquith and Michael Powell before becoming the latter's continuity clerk. Among other films she worked on was William Beaudine's Will Hay comedy, Boys Will Be Boys (1935), but she devoted her creative energies to writing dozens of short plays with Sydney, the majority of which focused on female protagonists.

Despite being so prolific, the newly married pair remained in their day jobs until Sydney opened Verity Films in 1940. Buoyed by a loan from the Film Producers Guild, the company became Britain's biggest producer of wartime propaganda and training films, such as Harold Cooper's Jane Brown Changes Her Job (1942), which can be found in the Imperial War Museum collection, Women and Children At War.

Sydney and Muriel worked on everything from budgets to scripts, with the former even turning director with Ten Tips For Tackling Tanks (1942), which is available to rent on British Tanks At War. Such was Verity's standing that Sydney bought out Green Park Productions and moved into features with Jeffrey Dell's The Flemish Farm (1943), which paid tribute to the Belgian resistance movement. Taking an office at Riverside Studios, the Boxes enjoyed modest success with Henry Cass's 29 Acacia Avenue (1945) and Compton Bennett's The Years Between (1946). But their greatest triumph during this period of independent production was the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay that Sydney and Muriel won for Bennett's The Seventh Veil (1945), which broaches the subject of psychoanalysis in showing how doctor Herbert Lom identifies pianist Ann Todd's relationship with cruel guardian James Mason as the reason for her attempted suicide.

Rather than build on this accolade, however, the Boxes accepted J. Arthur Rank's offer to join Gainsborough. With Sydney as Managing Director and Muriel in charge of the script department, the studio scored a resounding hit with Carol Reed's Holiday Camp (1947), in which Jack Warner and Kathleen Harrison so caught the public imagination as an ordinary working-class couple that they were reunited for Ken Annakin's Here Come the Huggetts (1948), which can be found on The Huggetts Collection, alongside the same director's Vote For Huggett and The Huggetts Abroad (both 1949). The couple also renewed their writing partnership on Lawrence Huntington's When the Bough Breaks (1947) and Bernard Knowles's Easy Money (1948).

As Sydney preferred this brand of social realism, he steered Gainsborough away from trademark period melodramas like Leslie Arliss's The Wicked Lady (1945) after the comparative failure of Bernard Knowles's Margaret Lockwood starrer, Jassy (1947). Instead, he favoured titles with a contemporary feel, such as David McDonald's Snowbound (1948), Antony Darnborough and Terence Fisher's The Astonished Heart and So Long At the Fair (both 1950), and the three multi-directed anthologies adapted from the writings of W. Somerset Maugham: Quartet (1948), Trio (1950) and Encore (1951).

By the time the latter pair were released, the Boxes had become so disillusioned with the British film industry after Rank's closure of Gainsborough that they had taken a year-long break to explore France and the United States. They returned in 1951 when Sydney founded Independent Producers, which would go on to sponsor such diverse pictures as Peter Glenville's The Prisoner (1955), Charles Crichton's Floods of Fear (1958), Darcy Conyers's The Night We Dropped a Clanger, Alvin Rakoff''s The Treasure of San Teresa (both 1959) and Wolf Rilla's Piccadilly Third Stop (1960).

More significantly, the new company afforded Muriel the chance to direct, at a time when Britain's only other prominent woman film-maker, Wendy Toye, was alternating between thrillers and comedies with such features as The Teckman Mystery (1954), Three Cases of Murder and All For Mary (both 1955). Muriel's sister-in-law, Betty, was also on the crest of a wave during the 1950s and such was their prominence that Noël Coward fondly dubbed them 'The Brontës of Shepherd's Bush'. But Muriel's achievement has been somewhat undersold.

She had been lined up to make So Long At the Fair, but star Jean Simmons had refused to be directed by a woman. Consequently, the 47 year-old Muriel followed her co-credit with Bernard Knowles on The Lost People (1949) with a solo debut with The Happy Family (1952), a topical Ealingesque comedy that sees Stanley Holloway and Kathleen Harrison refuse to leave their family home, even though it has been requisitioned for demolition as part of the Festival of Britain project.

Co-scripting with Sydney, Muriel provided another snapshot of London life in Street Corner (1953), a WPC companion piece to Basil Dearden's The Blue Lamp (1950) that followed a day on the beat with constables Anne Crawford and Barbara Murray reporting to sergeant Rosamund John about cases involving good-time girl Peggy Cummins and accidental heroine, Eleanor Summerfield. Having scored a hit with The Beachcomber (1954), another Maugham adaptation that saw Donald Sinden take over the role that had been played with such gusto by Charles Laughton in Erich Pommer's 1938 take on the tale, Vessel of Wrath.

Sadly, these titles are currently unavailable on disc and the same is true for Muriel's Eyewitnes (1956), The Other Eden and Subway in the Sky (both 1959). However, Cinema Paradiso can offer her comic duo of To Dorothy, a Son (1954) and Simon and Laura (1955). The former stars Shelley Winters, as a New York showgirl who hot foots to Britain after she learns that she stands to inherit $2 million from an uncle if ex-husband John Gregson hasn't produced an heir, only to discover new wife Peggy Cummins is about to give birth at any moment. Anticipating today's celebrity-obsessed Reality culture, the latter sees BBC producer Ian Carmichael persuade bickering actors Peter Finch and Kay Kendall to appear in a nightly soap opera based on their lives.

Unfortunately, Kendall tried to have Muriel fired, as she disliked being told what to do by another woman. Sydney stood by his wife, however, and encouraged to experiment, Muriel switched between monochrome and colour while flitting between the real and imagined sequences in The Passionate Stranger, a satire on romantic fiction that stars Margaret Leighton as a novelist who is tempted during husband Ralph Richardson's illness to flirt with Italian chauffeur, Carlo Giustini. Emboldened, Muriel littered The Truth About Women (both 1957) with flashbacks, as Laurence Harvey reminisces about his dalliances with Diane Cilento, Eva Gabor and Mai Zetterling in an emotional rite of passage that recalls Ernst Lubitsch's Heaven Can Wait (1943).

While Sydney was in Hollywood negotiating a deal to make a film about William the Conqueror, he suffered a cerebral haemorrhage and entrusted his business affairs to his brother-in-law, Peter Rogers, who had married Betty in 1948. We shall hear much more about him in due course. But, for now, Muriel found herself nursing her husband while trying to complete Too Young to Love (1960), an adaptation of Elsa Shelley's play, Pickup Girl, that earned an X certificate and much disapproving newspaper coverage for its tale of teenage prostitution and abortion. However, she took a very different tack with The Piper's Tune (1962), which was produced for the Children's Film Foundation, several of whose enduringly popular adventures are available from Cinema Paradiso.

In 1964, Sydney tried to make a comeback as the producer of Muriel's sex comedy, Rattle of a Simple Man, which teamed Harry H. Corbett and Diane Cilento as a northern football fan and the escort he meets while in London for the Cup Final. But, despite playing a behind the scenes role on Ralph Thomas's Deadlier Than the Male (1966), Sydney drifted out of show business. Indeed, having suffered a series of heart attacks and divorced Muriel, he emigrated to Australia, where he wrote a handful of whodunits before dying in Perth on 26 May 1983. Now Baroness Gardiner, after marrying a former Lord Chancellor in 1970, Muriel also moved into the literary world when she formed the Femina publishing house with Vera Brittain, whose celebrated autobiography, Testament of Youth, has been adapted for television by Moira Armstrong in 1979 and filmed by James Kent in 2014. She also wrote a number of novels before passing away on 18 May 1991. Three decades later, she remains Britain's most prolific woman director.

Woolfs At the Door

If Michael Balcon had shown little faith in Muriel Box in refusing her the funds for a lavish modern-day Romeo and Juliet saga, he had backed Alfred Hitchcock to the hilt in the face of continued criticism from his boss at Gaumont-British. Chester Moss Woolf may have co-produced Downhill (1927) and Easy Virtue (1928), but he had been convinced that The Lodger would ruin the studio's reputation. Indeed, as late as 1934, he was still complaining that Hitch's classic thriller, The Man Who Knew Too Much, lacked finesse. Two decades later, Woolf's son, John withdrew his support for The Happy Family when he discovered that Sydney and Muriel were not planning to direct together, as he wasn't convinced that a woman's place was in the director's chair.

One of 10 children born to a London furrier and his wife, Charles had fathered Eton-educated half-brothers John and James before he made enough money from continental movie imports to invest in Tarzan adventures and Harold Lloyd comedies from Hollywood in the 1920s. Having been bought out by Isidore Ostrer in 1927, Charles spent eight years running Gaumont-British's distribution operation. But he decided to strike out alone by forming General Film Distributors, with flour tycoon J. Arthur Rank among his backers. This gave him access to Pinewood Studios, while a couple of ennobled partners secured him a connection with Universal Studios that enabled him to survive the dip in British cinematic fortunes during the mid-1930s. In 1941, when Rank took over Oscar Deutsch's Odeon cinema chain, Charles allowed him to use GFD's logo of a bare-chested man striking a gong and, in return, he became a major player in the Rank Organisation.

Sadly, Charles didn't get to enjoy his new status for long, as he died following an operation on an ulcer on 31 December 1942. However, his sons were more than ready to step into his shoes, with John having rejoined GFD after making propaganda films for the War Office. He quit Rank after a row with managing director John Davis over Eagle-Lion being given preferential treatment over GFD. Joining forces with his half-sibling, John formed both Independent Film Distributors and Romulus Films, which offered a sanctuary to American directors who had been blacklisted in Hollywood during the House UnAmerican Activities Committee's investigation into Communism in the entertainment industry.

The new company got off to an impressive start with Albert Lewin's Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951), which teamed James Mason and Ava Gardner in a brooding romance. But they struck gold in hooking up with John Huston for The African Queen (1951), an adaptation of C.S. Forester's novel that saw Humphrey Bogart win the Academy Award for Best Actor as Great War maverick Charlie Allnutt opposite Katharine Hepburn's missionary, Rose Sayer. Romulus also back Huston's triple Oscar-winning Toulouse-Lautrec biopic, Moulin Rouge (1952), and his gleefully offbeat Italian odyssey, Beat the Devil (1953), which paired Bogart with Jennifer Jones.

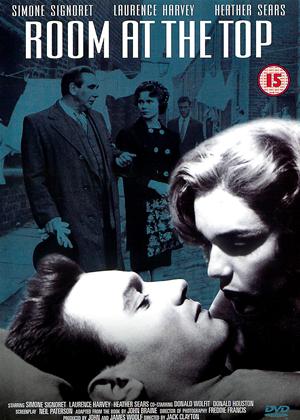

Guided by Sir Alexander Korda, the Woolfs also promoted emerging British talents like Lewis Gilbert on the X-rated Cosh Boy (1953) and The Good Die Young (1954) and Jack Clayton on The Bespoke Overcoat (1956), Room At the Top (1959) and The Pumpkin Eater (1964), respective adaptations of works by Nikolai Gogol, John Braine and Penelope Mortimer that scooped the Oscars for Best Live-Action Short and Best Actress (for Simone Signoret) and the Best Actress prize at Cannes, a BAFTA, a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination for Anne Bancroft.

In 1955, following divorces from actresses Dorothy Vernon and Edana Romney, John married Victor Saville's daughter, Ann, who remained his wife until his death. He also invested £1 million in four properties that Korda had been forced to sell when British Lion went into receivership. The resulting pictures couldn't have been more different, as Carol Reed's adaptation of Wolf Mankiewicz's A Kid For Two Farthings was set in London's East End; Zoltan Korda's Storm Over the Nile reworked A.E.W. Mason's The Four Feathers (which Korda had directed in 1939); Laurence Olivier's Oscar-nominated interpretation of William Shakespeare's Richard III harked back to the War of the Roses; while David Lean's Summertime took Katharine Hepburn to Venice. The brothers would reunite with Hepburn for Ralph Thomas's The Iron Petticoat (1956), a reworking of Ernst Lubitsch's Ninotchka (1939) that provoked tensions on set with Bob Hope, who kept adding unrehearsed gags in order to upstage his co-star.

Recognising James's burgeoning talent as a producer, John formed Remus Films to give him some creative freedom. The Woolfs also signed Laurence Harvey to an exclusive contract and starred him in films as varied as Henry Cornelius's I Am a Camera (1955), Ken Annakin's Three Men in a Boat (1956) - which were respectively adapted from novels by Christopher Isherwood and Jerome K. Jerome - and William Fairchild's Second World War submarine adventure, The Silent Enemy (1958). They also tempted Hollywood icons like Joan Crawford into headlining items like David Miller's The Story of Esther Costello (1957), while also sponsoring such diverse projects as Anthony Asquith's Carrington V.C. (1955), Gordon Parry's Sailor Beware (1956) and Gerald Thomas's The Vicious Circle (1957). Yet, when Thomas and producing partner Peter Rogers offered John a stake in Carry On Sergeant (1958), he turned them down and forever regretted missing out on the long-running franchise.

Having played his part in bringing the Kitchen Sink stylings of the Royal Court's Angry Young Men to British screens, John teamed Laurence Olivier and Simone Signoret in Peter Glenville's Term of Trial (1962), recruited Leslie Caron for Bryan Forbes's adaptation of Lynne Reid Banks's The L-Shaped Room (1962) and rehired Laurence Harvey to reprise the role of Joe Lambton in Ted Kotcheff's Life At the Top (1965). Yet, he also cast comic genius Peter Sellers in Cliff Owen's The Wrong Arm of the Law and John Boulting's Heavens Above! (both 1963).

While John was signing Kim Novak to grace Ken Hughes's take on Somerset Maugham's Of Human Bondage (1964), James and screenwriter Bryan Forbes were trying their luck in Hollywood with an adaptation of James Clavell's POW drama, King Rat (1965). However, this proved to be his final assignment, as the 46 year-old James died suddenly on 30 May 1966. Shaken by the loss of his brother, James took time away from cinema, but returned to produce Carol Reed's Oliver! (1968), Lionel Bart's musicalisation of Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist , which surprised many by taking the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Five years would pass before John returned to the fray, however, when he followed an executive role on Cliff Owen's No Sex Please: We're British (1973) by producing two thrillers based on Frederick Forsyth bestsellers, Fred Zinnemann's The Day of the Jackal (1973) and Ronald Neame's The Odessa File (1974). These turned out to be the last Woolf features, although John (as a co-founder of Anglia Television) did serve as executive producer on Christopher Miles's tense sci-fi saga, Alternative 3 (1977), and two markedly different series, Orson Welles: Great Mysteries (1974-77) and Tales of the Unexpected (1977-89), which were introduced by their creator, Roald Dahl.

He became Sir John Woolf in 1975 and made a tidy sum by running British and American Film Holdings as an investment trust before his death at the age of 86 on 28 June 1999. In all, his films amassed 13 Oscars after he had ignored Korda's advice about not touching The African Queen with a barge pole because no one would pay to see 'two old people going up and down an African river'.

Betty Box Office

Back in 1942, Sydney Box had invited his younger sister, Betty, to join Verity Films. Trained as a commercial artist, she had also taken courses in shorthand and accountancy and quickly proved to be a versatile asset to the company. During the course of the war, she made contributions to over 200 documentaries and became familiar with every aspect of the film-making process. Consequently, when Sydney was headhunted by Gainsborough, he entrusted Betty with the running of Islington Studios, where she took a number of associate producer credits before enjoying considerable success with such early producing projects as Arthur Crabtree's Dear Murderer (1947) and Ken Annakin's Miranda (1948), in which Glynis Johns memorably plays a mermaid.

On 24 December 1948, Box married fellow producer Peter Rogers who shared her feel for popular taste. They also concurred that, while critical acclaim was nice, commercial success was even more important because it took cash to create. This mantra earned Box the trust of J. Arthur Rank when she followed her brother to Pinewood, where she made the acquaintance of Ralph Thomas. Over the next three decades, their partnership would act as a barometer for the fortunes of the British film industry, while Rogers would forge an equally enduring link with Thomas's younger brother, Gerald.

Born in Hull on 10 August 1915, Ralph Thomas was the nephew of Victor Saville. Having gone into journalism, he so impressed Odeon chief Oscar Deutsch with a perceptive profile that he was invited to the Sound City studio at Shepperton. Working his way up from clapper-boy to camera assistant, Ralph spent four years in the editing rooms at Shepperton, Elstree and Isleworth before seeing wartime action with the 9th Lancers. Following a stint as an instructor at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, he became a trailer editor at Gainsborough. He met Betty Box while working on Miranda and she helped persuade Sydney that Ralph was ready to direct.

Teamed with producer Antony Darnborough, Ralph made his directorial bow with Once Upon a Dream, which he followed later in 1949 with the delightfully dotty Helter Skelter, in which radio celebrity David Tomlinson falls for Carol Marsh while she's searching for a cure for her hiccups. Meanwhile, Betty was similarly engaged with comic diversions like Roy Rich and Alfred Roome's It's Not Cricket and Arthur Crabtree's Don't Ever Leave Me (both 1949). But, in collaborating for the first time, Betty and Ralph changed tack with The Clouded Yellow (1950), a tense, cross-country thriller that centres on the efforts of ex-spy Trevor Howard to prove that fugitive Jean Simmons has been framed for murder.

Fortunately, the film was a success, as Betty had mortgaged her own home to secure a vital bank loan. However, Ralph reunited with Darnborough for Traveller's Joy (1950), which starred the married duo of Googie Withers and John McCallum. But, for the rest of their careers, Ralph Thomas and Betty E. Box formed a team that proved so profitable that she earned the nickname, Betty Box Office'.

Following the Channel Island war comedy, Appointment With Venus (1951), Betty and Ralph returned to suspense with the Venetian Bird (1952), which contained echoes of Carol Reed's The Third Man (1949), as Richard Todd heads to Venice in search of shady partisan hero John Gregson. They also remained on the continent with A Day to Remember (1953), which followed Stanley Holloway's pub darts team on a day trip to Boulogne.

While these pictures did steady business, they hit the bullseye with their next outing, an adaptation of Richard Gordon's Doctor in the House (1954), which they made in spite of objections from Rank's stern lieutenants, John Davis and Earl St John. Not only would this hugely popular comedy spawn a long-running series that would include Doctor At Sea (1955), Doctor At Large (1957), Doctor in Distress (1963), Doctor in Clover (1966) and Doctor in Trouble (1970), but it also led to an ITV spin-off series, Doctor in the House (1969), which boasted the Monty Python duo of John Cleese and Graham Chapman and future Goodies Graeme Garden and Bill Oddie among its writers.

Moreover, in returning to St Swithin's Hospital to play Dr Simon Sparrow opposite James Robertson Justice's Sir Lancelot Spratt, Dirk Bogarde became Britain's biggest film star, and the Idol of the Odeons was so grateful to Betty and Ralph that not only did he make three more Doctor comedies, but he also headlined such weightier dramas as the Charles Dickens adaptation, A Tale of Two Cities (1958), as well as the military adventures Campbell's Kingdom (1957), The Wind Cannot Read (1958), Hot Enough For June (1964) and The High Bright Sun (1965), which were respectively set in the Canadian Rockies, Delhi, Prague and Cyprus.

As the decade progressed, Ralph and Betty continued to take sly swipes at the Establishment with their ribald insights into class, deference and the battle of the sexes, as they alternated between such crowd-pleasing light entertainments as the Miranda sequel, Mad About Men (1954), and patriotic flag-wavers like Above Us the Waves (1955), gripping recreation of the sinking of the German battleship Tirpitz, which starred Johns Mills and Gregson. Similarly, the aforementioned Hope-Hepburn teaming on The Iron Petticoat presaged two contrasting thrillers, Anthony Asquith's moto-espionage saga, Checkpoint (1956), and a reworking of John Buchan's The 39 Steps (1959), which stuck closely to Alfred Hitchcock's 1935 original in replacing Robert Donat with Kenneth More as Richard Hannay.

In 1958, Betty was awarded the OBE for services to cinema and she responded by producing one of the first British films to focus on the Holocaust, Conspiracy of Hearts (1960), which shows how Italian major Ronald Lewis finds himself at odds with Nazi colonel Albert Lieven over the Jewish children being sheltered in the convent run by Mother Superior Lilli Palmer. Ralph and Betty also explored the pitfalls of the political system in profiling Peter Finch's Labour MP in No Love For Johnnie (1961). However, while it was business as usual as Juliet Mills sought to rebel against father Michael Redgrave in No, My Darling Daughter! (1961), the patented Rank formula had started to seem glib in the face of the social realist boom.

Betty was keen to explore more everyday topics, but her reputation with the front office dipped after she turned down Canadian Harry Saltzman's offer to collaborate on an adaptation of Ian Fleming's Dr No, which cost Rank the chance to land the James Bond franchise. Ralph tried to bail her out by starring Richard Johnson as Bulldog Drummond in Deadlier Than the Male and Some Girls Do (1969), and Rod Taylor as Australian sleuth Scobie Malone in the conspiracy thriller, Nobody Runs Forever (1968). But the pictures lacked the glamour and grit of Sean Connery's 007 outings and Betty and Ralph saw their partnership peter out rather meekly with the sex comedies, Percy (1971), The Love Ban (1973) and Percy's Progress (1974).

Having fought an uphill battle for so long to compete in a male-dominated industry, Britain's highest-profile female producer called it a day, although Ralph would have one last hurrah in casting David Niven against type as a London gangland boss in A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square (1979). They would enjoy happy retirements before Betty succumbed to cancer on 15 January 1999 and Ralph followed on 17 March 2001. But cinema remained central to their lives, as she was married to the producer of the Carry On films that were directed by his brother. Moreover, Ralph's son, Jeremy, also proved a chip off the old block.

A Right Carry On

Peter Rogers was born in Chatham, Kent on 20 February 1914. Like his future brother-in-law, he started out writing plays while working as a reporter and struck lucky when actress-producer Auriol Lee took him to the West End as her assistant. Despite his first two plays running for a grand total of 17 days between them, Rogers spent the war writing radio dramas for the BBC and cutting his cinematic teeth by writing homilies for Rank's Religious Films unit. He was writing for Picture Post when Sydney Box discovered him, however, and invited him to help script Holiday Camp at Gainsborough.

Supported by his new wife, Rogers won a prize at the Venice Film Festival as the producer of Ralph Thomas's The Dog and the Diamonds (1953). However, he allowed Betty to lay claim to Ralph, while he threw in his lot with his younger brother, Gerald. Born in Hull on 10 December 1920, Gerald had abandoned his medical studies to serve with the Sussex Regiment during the war. On being demobbed, he decided to follow his sibling into the movie business and started out in the cutting room at Denham Studios, where he gained experience as an assistant editor on features like Roy Ward Baker's The October Man (1947) and Laurence Olivier's Hamlet (1948), which became the first British title to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. Gerald also served as an associate editor on The Third Man before his brother recruited him to edit Leslie S. Hiscott's The 20 Questions Murder Mystery (1950); which can be found on Renown's Crime Collection ), Appointment With Venus, Brock Williams's I'm a Stranger (1952), A Day to Remember and Doctor in the House.

Having cut Ken Annakin's Disney period drama, The Sword and the Rose (1953), which starred James Robertson Justice as Henry VIII and Glynis Johns as Mary Tudor, Gerald teamed up with Rogers, who had just earned a writing credit on Maurice Elvey's greyhound romp, The Gay Dog (1954). After making a promising start with Circus Friends (1956) for the Children's Film Foundation, the pair followed the thrillers Time Lock and The Vicious Circle (both 1957) with The Duke Wore Jeans (1958), a Tommy Steele musical with songs by Lionel Bart and a screenplay by Norman Hudis. He had also adapted R.F. Delderfield's play, The Bull Boys, as Carry On Sergeant and Rogers bought the script as a project for future Doctor Who William Hartnell.

With so many young men doing National Service, the antics of Kenneth Williams, Charles Hawtrey and Kenneth Connor found a ready audience. But Rogers wasn't thinking of making a follow-up, as he produced Gerard Bryant's The Tommy Steele Story, Alfred Shaughnessy's Cat Girl and Compton Bennett's The Flying Scot (all 1957), as well as Gerald's neat slice-of-life saga, Chain of Events, and the unsettling murder mystery, The Solitary Child (both 1958). Even when Carry On Nurse (1959) topped the annual box-office chart and ran in one Los Angeles theatre for two and a half years. Rogers and Thomas continued to make a range of non-series comedies, including Please Turn Over, Watch Your Stern, No Kidding (all 1960), Raising the Wind (1961), The Iron Maiden (1962) and The Big Job (1965).

Most of these pictures featured members of what was becoming known as the Carry On team, with Twice Round the Daffodills (1962) even recycling the same Patrick Cargill and Jack Beale play, Ring For Catty, that had inspired Carry On Nurse. The likes of Sidney James, Leslie Phillips, Hattie Jacques and Joan Sims became household names, as Hudis combined farce, innuendo and subversive satire in such workplace scenarios as Carry On Teacher (1959), Carry On Constable (1960), Carry On Regardless (1961) and Carry On Cruising (1962).

When he left the fold, Talbot Rothwell continued in a similar vein with Carry On Cabby (1963). But he persuaded the famously pennywise Rogers to branch out into movie spoofs with Carry On Jack (1963), Carry On Spying, Carry On Cleo (both 1964), Carry On Cowboy (1965) and Carry On Screaming! (1966), which introduced younger talents like Jim Dale, Angela Douglas and Barbara Windsor. With Amanda Barrie in the title role, Cleo took advantage of the chaos surrounding Joseph L. Mankiewicz's Cleopatra (1963), by using some of the sets that had been left at Pinewood when the production moved to Rome.

Up until this point, the critic-proof comedies had been distributed by Anglo-Amalgamated. But it withdrew its backing in 1967 and Rank had to release Don't Lose Your Head and Follow That Camel without the famous prefix. Respectively set during the French Revolution and in the French Foreign Legion, the pair have seen become part of the Carry On collection. But Rogers was wary of over-investing in such costly period pieces and, while he dipped into the past for Carry On Up the Khyber (1968), Carry On Up the Jungle (1970), Carry On Henry (1971) and Carry On Dick (1974), he started to steer the series back towards the present day in an effort to keep down costs.

Exploiting the relaxation of censorship rules in the middle of the Swinging Sixties, Rothwell began to make the jokes bawdier, while Rogers and Thomas agreed to making the costumes skimpier in such snapshots of their times as Carry On Doctor (1967), Carry On Camping, Carry On Again Doctor (both 1969), Carry On Loving, Carry On At Your Convenience (both 1971), Carry On Matron, Carry On Abroad (both 1972), Carry On Girls and the TV special, Carry On Christmas (both 1973).

By now, Bernard Bresslaw, Peter Butterworth, Jack Douglas and Patsy Rowlands had become recurring members of the troupe. But the series never recovered from the death of Sid James after he had scored a solo hit in Thomas's Bless This House (1972), which had been spun off from a much-loved ITV sitcom (1971-76). With Rothwell also now departed, Rogers struggled to find a replacement of the same calibre and even stalwarts like Williams and Connor began to go through the motions in such late entries as Carry On Behind (1975), Carry On England (1976) and Carry On Emmannuelle (1978), which satirised the vogue for softcore pornography that had become the staple of British cine-comedy during one of the film industry's bleakest phases.

To his credit, Rogers avoided going down this route, as he sought to add strings to his bow with Sidney Hayers's Assault, Revenge (both 1971) and All Coppers Are... (1972). He even stepped into his wife's shoes to produce Ralph Thomas's Quest For Love (1971), but it proved to be a one-off. Quick to spot a money-spinning opportunity, however, Rogers released That's Carry On (1979) as a 'greatest clips' package and sought to team Jim Dale with a new generation of comedians in Carry On Columbus (1992).

This proved to be a resounding misfire and neither Rogers nor Thomas made another feature. The former worked hard to maintain the legacy, with four different clip shows cropping up on television between 1975-93. Gerald's death on 9 November 1993 hit Rogers hard, however, and there was a certain sadness when he quipped on declining an invitation to a 1994 retrospective at The Barbican, 'What a punishment! Even the Marquis de Sade couldn't have devised a worse torture.' He died at the grand old age of 95 on 14 April 2009, by which time his old partner's nephew had firmly established himself in the arthouse circles that were a world away from the remainder of the Saville-Box-Woolf-Rogers-Thomas oeuvre.

The Boy Done Good

If cinema wasn't already in Jeremy Thomas's blood, being born in the shadow of Ealing Studios on 26 July 1949 seemed to reaffirm his destiny to follow his father and uncle into the film business. On leaving school, he sought work as an editor. But rather than calling in family favours, Thomas did his apprenticeship on such different assignments as Ken Loach's Family Life (1971), Perry Henzel's The Harder They Come (1972) and Gordon Hessler's The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973).

Having pieced together fragments of footage from the Great Depression for Philippe Mora's powerful documentary, Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? (1975), Thomas felt ready to make the step up to producing and reunited with Mora on the Bush Western Mad Dog Morgan (1976) which is one of the key works of the Australian New Wave that is discussed in Mark Hartley's revealing documentary, Not Quite Hollywood (2008). Although he hasn't worked with Mora since, Thomas has returned Down Under for Philip Noyce's Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002).

Moreover, he has tended to forge bonds with film-makers since launching the Recorded Picture Company with The Shout (1978), a disconcerting chiller starring Alan Bates, Susannah York and John Hurt that was made by the exiled Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski, with whom Thomas reunited 32 years later for Essential Killing (2010). Often favouring arthouse over the mainstream, Thomas has since worked regularly with an eclectic mix of film-makers from around the world. Most notably, he collaborated with Nicolas Roeg on Bad Timing (1980), Eureka (1983) and Insignificance (1985); Julien Temple on The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle (1980) and Glastonbury (2006); David Cronenberg on Naked Lunch (1991), Crash (1996) and A Dangerous Method (2011); Wim Wenders on Don't Come Knocking (2005) and Pina (2011); Terry Gilliam on Tideland (2005) and The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (2018); and Matteo Garrone on Tale of Tales (2015) and Dogman (2018).

By far his most beneficial partnership was with Bernardo Bertolucci, as they won the Academy Award for Best Picture with The Last Emperor (1987), a lavish biopic of China's last imperial ruler, Pu Yi, that was partially filmed in Beijing's Forbidden City. Thomas would go on to produce Bertolucci's The Sheltering Sky (1990), Little Buddha (1993), Stealing Beauty (1996) and The Dreamers (2003). But he has preferred working in Japan to China since following Nagisa Oshima's Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence (1983) and Gohatto (1999) with Takeshi Kitano's Brother (2000) and four features with the prolific Takashi Miike: 13 Assassins (2010), Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai (2011), Blade of the Immortal (2017) and First Love (2019).

Shrugging off the failure of his sole directorial venture, All the Little Animals (1998), Thomas showed a nice touch of self-deprecating humour with a cameo in James Toback's bittersweet Cannes exposé, Seduced and Abandoned (2013). Since founding HanWay Films in 1998, he has plumped for the odd continental project, including Edgar Reitz's Heimat 3: A Chronicle of Endings and Beginnings (2005) and Joachim Rønning and Espen Sandberg's Kon-Tiki (2012), which scooped Oscar and Golden Globe nominations for Best Foreign Film. But Thomas has also become a darling of the US Indie Scene with such offerings as Karel Reisz's Everybody Wins (1990), Bob Rafelson's Blood and Wine (1996), Johnny Depp's The Brave (1997), Richard Linklater's Fast Food Nation (2007) and Jim Jarmusch's Only Lovers Left Alive (2013). No wonder he was presented with the European Film Award for Outstanding European Achievement in World Cinema in 2006.

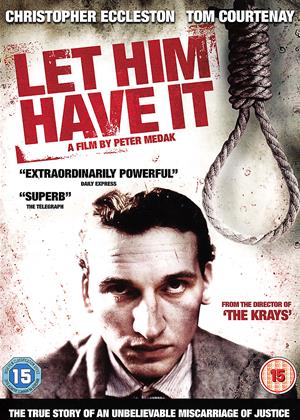

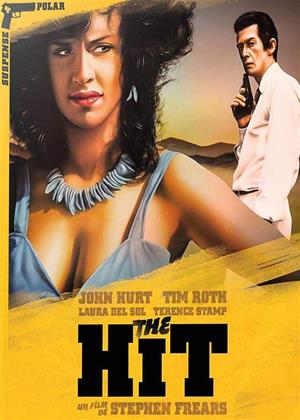

However, the recipient of a CBE and BAFTA's Michael Balcon Award for Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema regularly returns to his roots for such contrasting projects as Stephen Frears's The Hit (1984), Peter Medak's Let Him Have It (1991), Jonathan Glazer's Sexy Beast (2000), David Mackenzie's Young Adam (2003), Jon Amiel's Creation (2009), Richard Shepard's Dom Hemingway (2013) and Ben Wheatley's High-Rise (2015), which are a far cry from the silents made by his Great Uncle Victor a century ago.