One of the great things about Cinema Paradiso is that you can watch whatever you want whenever you want. This isn't always true at your local cinema, however, especially during the first few weeks of the year. Here's all you need to know about what industry insiders call 'the dump months'.

During the Golden Age of Hollywood, the major studios owned their own theatre chains to ensure that their films always had somewhere to play. Moreover, a system known as 'block booking' meant that smaller independent venues had to show a proportion of a studio's lesser offerings in return for access to their prestige pictures, which were often given 'road show' rollouts that enabled the studios to charge premium prices for tickets in their big city flagship theatres before releasing them in downtown and neighbourhood cinemas nationwide.

In 1948, the US Supreme Court decided that this practice constituted an illegal monopoly, as it essentially gave the studios a captive audience. The judgement in the case of the United States v Paramount Pictures ordered the studios to divest themselves of their theatres, which meant they no longer had a guaranteed outlet for their wares. As a rise in television ownership and a population drift to the suburbs had already prompted a box-office decline following the record takings of 1946, the studio moguls realised that they could no longer just release features when it suited them. Instead, in order to maximise profits, they had to revise their strategies and start releasing their most anticipated titles at the peak attendance times tied to federal and school holidays.

The eligibility rules of major awards like the Oscars and the Golden Globes also began influencing the timing of new releases, as the studios strove to keep their contenders in the minds of voters while they were deliberating about their nominations. The advent of the blockbuster era in the mid-1970s placed even more emphasis on marquee openings during the summer vacation period and the traditional end-of-year holidays.

As a consequence, January and February became dead zones for new releases. However, as longtime Hollywood player Tom Ortenberg told the New York Times Magazine, 'there is never a bad time to release a good film - and there is never a good time to release a bad film'.

So What Is a Dump Month?

Although the names of the old studios still appear at the start of many Hollywood movies, the system built around them has long gone. Nowadays, they lease out soundstage space to largely self-contained production units and then broker distribution deals for the resulting features. This means, they are contractually obliged to secure release slots and those with limited commercial prospects find themselves being dumped into what are considered the calendar's dead zones.

The term 'dump month' was seemingly coined by critic Jonathan Bernstein in a 2007 article in The Guardian, in which he pointed out the habit of releasing 'films no studios believe in or care about' in the immediate post-Christmas period. Around the same time, Janet Maslin of The New York Times complained about having to endure a 'movie hell' filled with the 'flukes, black sheep, wild cards and also-rans' that the studios shovelled out with little fanfare in January and February in order to clear the decks for their spring releases.

One of the reasons why these particular months were chosen is that because people had less disposable income to spend on cinema tickets after the expense of the festive season, it made little sense to risk potentially commercial prospects when consumer spending was down. Inclement weather conditions exacerbate this reluctance to venture out on winter evenings, so the distributors became reluctant to bury potentially profitably pictures in snowdrifts.

Attention around the turn of the year is also dominated by the race for the Super Bowl, with Americans being more likely to stay home and watch a play-off game than check out what's showing at the local multiplex. It's been some time since the No.1 film for a Super Bowl weekend has been dislodged, as Bruce Hendricks's Hannah Montana and Miley Cyrus: Best of Both Worlds Concert (2008) has seen off all-comers, including the highest-ranking drama, Lasse Hallström's Dear John (2010).

In fact, US screens are mostly filled in January and February with the films that have been nominated for the Academy Awards. As the Oscars and other major prizes are restricted to titles that have been released in Los Angeles County for seven consecutive days before 31 December, producers tend to concentrate their hopefuls in the weeks leading up to the deadline so that they are fresh in the minds of the Academy members who are eligible to vote for them.

These titles filter into cinemas in the weeks following their big city premieres and tend to linger as audiences catch up with the films likely to be competing for the major gongs. Recognising the difficulty of competing against features of this quality, distributors stuff the schedules with lesser items that have either fared poorly at test screenings or have been panned by the critics. As film buffs will already have seen the Oscar bait, they are happy enough to patronise these misfits and misfires, which wouldn't otherwise stand a chance of attracting a substantial audience.

It's also an industry truism that decent films released at the start of a year get forgotten by the Academy during the award season. As with any rule, however, there are exceptions, most notably Jonathan Demme's The Silence of the Lambs (1991), which was released in mid-February and went on to equal the record of another February release, Frank Capra's It Happened One Night (1934), in taking the Oscars for Best Picture, Director, Actor and Actress.

The dump months have also become a popular time to release indies that haven't generated much word of mouth, mid-range arthouse imports and horror movies. Once upon a time, these were reserved for Halloween, but chills can also be had on cold, dark winter nights, as Jordan Peele demonstrated in February 2017 with Get Out, which was not only nominated for the Academy Awards for Best Picture, Director and Actor (for Daniel Kaluuya), but it also won the category for Best Original Screenplay. Thrills also do decent business, with Breck Eisner's Liam Neeson vehicle, Taken (2008), among those to buck the trend and become a sizeable hit.

As we shall see below, the dump months have spawned numerous sleeper successes over the years. Second-rate teenpix have also been known to sneak under the radar, while date movie prospects improve considerably around St Valentine's Day. But, since records began in the early 1980s, takings in the first two months are invariably well down on any other time of the year.

There are two national holidays during this period, with Martin Luther King Day falling in January and Presidents' Day coming in February. Historically, however, they have yet to generate the same revenues as later dates like Labour Day and Thanksgiving. The current biggest hit to debut on Martin Luther King Day is Clint Eastwood's American Sniper, which took the title from the previous year's incumbent, Tim Story's Ride Along (both 2014), which has since been surpassed by Adil El Arbi and Bilal Fallah's Bad Boys For Life (2020). The three top-grossing Presidents' Day releases are Sam Taylor-Johnson's Fifty Shades of Grey (2015), Tim Miller's Deadpool (2016) and Ryan Coogler's Black Panther (2018), which is a rare example of a Marvel Cinematic Universe blockbuster being released in a dump month. However, this instant comic-book classic took advantage of the fact that February is Black History Month in the United States and scooped $235 million over the holiday weekend.

The emergence of streaming platforms has had an impact on the dead zone scene, as have lowered audience expectations, which have come to count as much as the actual calibre of the films on offer. Yet, despite features like John Patrick Shanley's Wild Mountain Thyme (2020) being picked up by online outlets, there has been no reduction in the amount of traditional dump month fodder making its way into cinemas. Indeed, the numbers continue to grow, although the pandemic has complicated the situation, as restrictions and closures have impacted upon attendances and prompted the postponement of tentpole releases in the hope that infection rates can be brought under control.

No one can say for sure how dump month statistics will pan out in future years. But, as James Surowiecki wrote in The New Yorker in 2015: 'If you release blockbusters in July and dogs in January, no wonder people go to the movies more often in July.' But these now-entrenched release patterns haven't always held sway.

Hooray For Heyday Hollywood

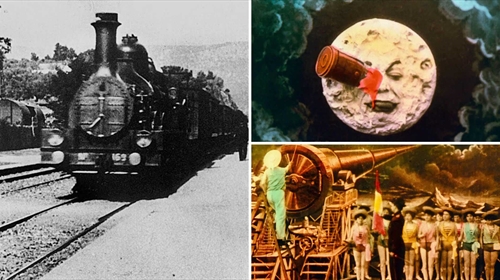

Having started out as a novelty item at fairgrounds and vaudeville theatres in the 1890s, cinema became an established pastime among America's urban lower and migrant classes following the opening of the first nickelodeon in June 1905. As the majority of films only lasted one or two reels, venues changed their programmes two or three times a week to maintain footfall. Moreover, as nascent production companies churned out content to meet demand, films were usually rush-released as soon as they were finished.

Turnover slowed after the introduction of features, however, and prestige items like D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation (1915) - which just happened to have been a January release - started to attract a new bourgeois audience. They demanded more salubrious settings than the neighbourhood flea pits that had started sprouting up across America's bigger towns. In the 1920s, therefore, exhibitors began building opulent dream palaces that made movie-going a special event.

As exhibitors charged extra for such luxury, they urged the burgeoning Hollywood studios to trust the intelligence of patrons and make their pictures more sophisticated. Not everything was as intellectually demanding as another January release, Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1924). But, while the studios recognised the value of debuting their most prestigious products on high days and holidays, crowdpleasers like Charlie Chaplin's The Kid (1921) were often released around the turn of the new year to help audiences banish the winter blues.

The inauguration of the Academy Awards in 1927 had a significant impact on Hollywood release patterns, as the studios sought to ensure that their leading contenders remained in the headlines in the run-up to voting. Presumably, no one felt that January and February constituted a dead zone when the first winner of the Oscar for Best Picture, William A. Wellman's Wings (1927), went on general release at the start of 1928, some five months after it had premiered.

Emil Jannings, the winner of the first Oscar for Best Actor, was cited for his work in both Victor Fleming's long-lost The Way of All Flesh (1927) and Josef von Sternberg's The Last Command (1928). Available to rent from Cinema Paradiso on high-quality DVD and Blu-ray, the latter was released on 22 January 1928. Returning to the screen after a lengthy break, Chaplin also chose the same month to send The Circus into cinemas. This went on to become the seventh highest-grossing title in silent screen history and Chaplin would have no compunction about releasing his first sound feature, Modern Times, on 11 February 1936.

Another to favour this time of year for major releases was Walt Disney, who gambled on issuing his first feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), in February 1938. Subsequently, Pinocchio went nationwide in February 1940. Yet, a decade would pass before Disney returned to the same month to release Cinderella (1950) and Peter Pan (1953). He later opted for January to launch another pantomime favourite, Sleeping Beauty (1959), and One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961). But the studio has largely steered clear of dump months since, with the notable exception of Fantasia 2000, which was somewhat understandably released on New Year's Day in 2000.

The first sound film to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards, Harry Beaumont's The Broadway Melody (1929), opened on 1 February and, when MGM came to launch Swedish siren Greta Garbo's first talking picture, they chose the same month in 1930 to push Clarence Brown's Anna Christie (1930). Four years later, following a December debut to qualify for the Oscars, Rouben Mamoulian's Queen Christina (1933), also hit cinemas in what would now be considered unfashionable February.

Although a growing number of households had radio sets, cinema dominated the American entertainment scene in the 1930s. Even during the Great Depression, people somehow found the money to go to the pictures and forget their troubles for a couple of hours. The Hollywood studios became film factories to keep the movie theatres supplied with star-filled features, B movies, serials, shorts, cartoons and news items. While the most anticipated pictures were held back for key release dates, the majority were presented as soon as they were ready to keep fans following their favourites and to allow the front offices to gauge the popularity and profitability of their contract players.

Guaranteed exhibition and a lack of leisure competition also meant there were no dead dates in the calendar. Consequently, at the height of the studio era, successive Januaries witnessed the release of Frank Capra's The Bitter Tea of General Yen, with Barbara Stanwyck; Lowell Sherman's She Done Him Wrong (both 1933), with Mae West and Cary Grant; George Cukor's David Copperfield (1935), with W.C. Fields; Raoul Walsh's High Sierra (1941), with Humphrey Bogart; Alfred Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt (1943), with Joseph Cotten; Hitchcock's Lifeboat, with Tallulah Bankhead; Clarence Brown's National Velvet, with Elizabeth Taylor (both 1944); and Howard Hawks's To Have and to Hold (1945), with Bogie and Lauren Bacall.

Over the same period, the February titles included Josef von Sternberg's Shanghai Express, with Marlene Dietrich; Tod Browning's cult classic, Freaks (both 1932); Howard Hawks's Bringing Up Baby (1938), with Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant; Ernst Lubitsch's To Be or Not to Be, with Jack Benny and Carole Lombard; and George Stevens's Woman of the Year (both 1942), with Hepburn and Spencer Tracy.

All of these titles are available from Cinema Paradiso, as are Preston Sturges's Sullivan's Travels and The Lady Eve, which were respectively released in January and February 1941. They found themselves up against Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh in Victor Fleming's Gone With the Wind, which had been showing exclusively in high-ticket road shows following its 1939 premiere and finally went into general release across the United States in January 1941. This is hardly a 'dump month' title and neither is Michael Curtiz's Casablanca (1942), with Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, which went into circulation in January 1943 to reflect the ongoing situation in North Africa during the Second World War.

Paramount and Beyond

The 1940s began with one of the most remarkable release rosters in Hollywood history, as 12-24 January saw Ernst Lubitsch's The Shop Around the Corner, with James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan; Howard Hawks's His Girl Friday, with Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell; and John Ford's The Grapes of Wrath, with Henry Fonda and Jane Darwell follow each other into US cinemas. As we have already seen, however, the decade ended with the imposition of the Paramount Decrees, which so badly dented the Hollywood working model that the studio system never completely recovered.

No longer assured of screen space in the nation's cinemas, the studios had to alter their release patterns to ensure that their biggest titles were released when the largest possible audience could see them. This meant shifting towards holiday releasing, even though there was always the risk that their rivals might be able to gazump them with their own marquee titles. This new approach didn't turn January and February into the dump months overnight, however. Indeed, classics like Robert Siodmak's The Spiral Staircase (1946), Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1946), John Huston's The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), and Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen's On the Town (1949) were all turn-of-year releases.

As the reality of the Paramount Decrees began to kick in, the studios became increasingly cautious about their release strategies. Yet significant titles continued to emerge at the start of each year, with Mervyn LeRoy's Quo Vadis? (1951), Stanley Donen's Seven Brides For Seven Brothers (1954), Alfred Hitchcock's To Catch a Thief (1955), Charles Walters's High Society, Henry King's Carousel (both 1956), and Hitchcock's North By Northwest (1959) being joined by two Best Picture winners, Cecil B. De Mille's The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) and Vincent Minnelli's Gigi (1958).

By this time, however, more American homes had television sets and armchair viewing took over from film-going as the nation's favourite leisure activity. With the grown-ups staying at home, the studios started catering to younger audiences, who preferred rock'n'roll to traditional musical tunes and horror and science fiction to social realism and the Western. Hence, the success of Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers, which was released in February 1956. Yet executives remained convinced that widescreen epics recreating key moments in history could still sell tickets and popcorn.

The 1960s proved a bleak decade for Hollywood, with the studios landing in the hands of multinational conglomerates and the Production Code falling victim to changing social attitudes. The risk-averse bean-counters now running the studios advocated a rationalised release schedule that meant the only major dump month releases of the entire decade were How the West Was Won (1963), which had segments directed by Henry Hathaway, John Ford and George Marshall, and Stanley Kubrick's Dr Strangelove or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964).

The situation improved slightly in the early 1970s, with both Robert Altman's M*A*S*H and Franklin J. Schaffner's Patton appearing on New Year's Day in 1970. But New Hollywood did little to change the commercial picture, with the result that the only February notables during the rest of the decade were Bob Fosse's Cabaret (1972), Mel Brooks's Blazing Saddles (1974) and Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976). And the dawning of the blockbuster era meant that the dump months would finally start living down to their nickname.

Dump Hard With a Vengeance

The colossal box-office success of films like Steven Spielberg's Jaws (1975) and George Lucas's Star Wars (1977) transformed the American film industry. Often accompanied by slick merchandising campaigns, banner movies were released at times that would allow the kind of fanboys who grew up to be Sheldon, Leonard, Howard and Raj in The Big Bang Theory (2007-19) to watch them several times before school resumed.

Fine films continued to be released at the start of the year, but they weren't youthquake titles. Some were sleeper hits, like Hal Ashby's Coming Home, which was released in February 1978 and found itself competing at the Academy Awards with another Vietnam drama, Michael Cimino's The Deer Hunter, which went nationwide the following year after premiering in Los Angeles to qualify for the Oscars. Others were schedule anomalies like Martin Scorsese's The King of Comedy (1983), which arrived in US cinemas two months after debuting in Iceland!

Despite solid reviews and fine performances by Jerry Lewis and Robert De Niro, this proved to be a flop. Unlike Herbert Ross's Footloose (1984), which was followed by a triumvirate of dump month classics in 1985: Joel and Ethan Coen's Blood Simple, John Hughes's The Breakfast Club and Peter Weir's Witness. Only the latter boasted a star name in Harrison Ford, with the other two being an indie debut and the vehicle that broke the unknowns who came to be dubbed 'The Brat Pack'.

Woody Allen enjoyed dead zone success with Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and Radio Days (1987), but his niche appeal rarely translated into box-office gold. The same was true of genial titles like David Jones's 84 Charing Cross Road (1987), John Waters's Hairspray (1988), and Steven Herek's Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure (1989). But, while these films have gone on to attract cult followings, the majority of dump month titles went the way of Pat O'Connor's fittingly titled The January Man (1989), even though this comedy thriller starring Kevin Kline as a maverick ex-cop on the trail of a New York serial killer is worth a second look, via Cinema Paradiso.

We've already seen how The Silence of the Lambs bucked all trends in 1991, while Penelope Spheris's Wayne's World (1992) and Harold Ramis's Groundhog Day (1993) proved in successive Februaries that funny films could brighten the winter gloom. Breakout films released at this time of year tended to be unexpected, however, as was the case with Ron Underwood's Tremors (1990), Ernest Dickerson's Juice (1992), Sam Raimi's Army of Darkness (1993), and Tom Shadyac's Ace Ventura, Pet Detective (1994).

But the bulk of the titles designated for January and February releases had been singled out for a reason. They weren't much good - which should send Cinema Paradiso users scurrying after such unmissables as Duncan Gibbins's Eve of Destruction (1991), Randall Miller's Houseguest (1995),

George P. Cosmatos's Shadow Conspiracy, Robert Butler's Turbulence (both 1997) and Tamra Davis's Half Baked (1998), so they can make up their own minds.

Entering the Millennium Dead Zone

As the new century dawned, filmgoers were greeted with a better than average raft of features that were headlined by such front-rank stars as Leonardo DiCaprio ( The Beach ), Bruce Willis ( The Whole Nine Yards ). Michael Douglas ( Wonder Boys ), and Ben Affleck ( The Boiler Room and Deception ). There was even a bona fide sleeper hit in the form of David Twohy's Pitch Black, which starred Vin Diesel as Riddick. But the curse of the dump months had not been lifted.

Lightning didn't strike twice for Anthony Hopkins, for example, as Ridley Scott's Hannibal failed to rise from the dead zone like The Silence of the Lambs. Jack Nicholson fared better with critics in Sean Penn's The Pledge, but this tense thriller struggled to find an audience. Cinema Paradiso users should definitely give it a go, however, and those seeking a little romantic escapism could do worse than Thomas Carter's Save the Last Dance and Adam Shankman's The Wedding Planner. But there were few takers for supposed clunkers like Peter Howitt's Antitrust, Francine McDougall's Sugar & Spice or Henry Selick's Monkeybone (all 2001).

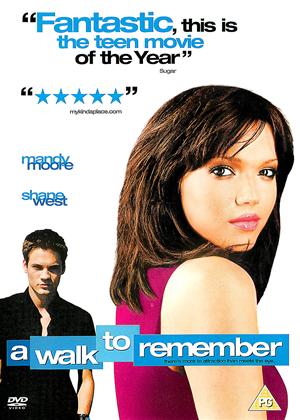

By now, it was becoming evident that what had once been quiet months for new releases were becoming a veritable dumping ground. In 2002, 55 features were deposited into the January and February schedules. A number were subtitled imports, but moneymakers like Kevin Reynolds's The Count of Monte Cristo and Adam Shankman's weepie, A Walk to Remember, were outnumbered by critically dismissed items like Steve Oderkerk's Kung Pow: Enter the Fist and Tamra Davis's Britney Spears vehicle, Crossroads, and such remakes as John McTiernan's Rollerball and Barry Skolnick's Mean Machine.

The consensus at Cinema Paradiso is that every film in our unrivalled 10,000-strong catalogue has something to recommend it and there's much to enjoyment to be had from the odd Bad Movie Night. But there was a reason that David McNally's Kangaroo Jack was released in January 2003, along with Chris Koch's A Guy Thing, Reggie Rock Blythewood's Biker Boyz, David R. Ellis's Final Destination 2, and Steve Guttenbergs's PS Your Cat Is Dead.

Compensation came in the form of David Gordon Green's All the Real Girls, which didn't deserve its box-office flop status. Twelve months later, Mel Gibson's provocative The Passion of the Christ debuted at the start of the year alongside such lesser lights as Cheryl Dunye's My Baby's Daddy, Joseph Kahn's Torque and Robert Luketic's Win a Date With Tad Hamilton! Defying the odds by selling tickets on the back of a critical panning were Eric Bress and J. Mackye Gruber's The Butterfly Effect, Chris Stokes's You Got Served and John Hamburg's Along Came Polly, which teamed Ben Stiller and Jennifer Aniston.

With romcoms, teenpix and mid-range actioners already doing steady business, Hollywood realised that horror movies could also do well during the dump months after Geoffrey Sax's White Noise became a sleeper hit in January 2005. The same wasn't true for Uwe Boll's Alone in the Dark, however, or for John Polson's Hide and Seek, in spite of the praise for Dakota Fanning's performance in being menaced by Robert De Niro. A dose of feel good also went down well in the cases of Andy Tennant's Hitch and Thomas Carter's Coach Carter, which respectively starred Will Smith and Samuel L. Jackson.

The same proved true in January 2006, when Emma Thompson's standout turn made Kirk Jones's Nanny McPhee a kidpic success. Overcoming critical disdain, Nicholaus Goossen's Grandma's Boy. John Whitesell's Big Momma's House 2 and Len Wiseman's Underworld: Evolution also set the tills ringing, while Shawn Levy's The Pink Panther somehow made more money with Steve Martin as Inspector Jacques Clouseau than Peter Sellers had ever done for director Blake Edwards.

Eli Roth's Hostel (2005) and Uwe Boll's BloodRayne (2006) found themselves at opposite ends of the spectrum where dump month horror was concerned. But the shocks came from the poverty of the comedy in titles like Brian Robbins's Norbit and Jason Friedberg and Aaron Seltzer's Epic Movie, as over 140 features were shoehorned into the Jan/Feb schedule in 2007. Among those to rise above the dross were Richard Lagravanese's Freedom Writers, while the standout from 2008 was undoubtedly Martin McDonagh's In Bruges, which hit US theatres a couple of weeks after impressing at the Sundance Film Festival.

In commercial terms, however, this hilarious comedy thriller trailed behind Matt Reeves's Cloverfield, which survived an 18 January release date to scoop $172 million worldwide. Making light of their dead zone releases, Anne Fletcher's 27 Dresses, Michel Gondry's Be Kind Rewind and Sylvester Stallone's Rambo performed respectably at the box office. But Jason Friedberg's Meet the Spartans, Ian Iqbal Rashid's How She Move and Eric Valette's One Missed Call rather justified their calendar slots.

As the decade closed, Pierre Morel's aforementioned Taken caught critics off guard by hitting a nerve with the public. Iain Softley's Inkheart and Thor Freudenthal's Hotel For Dogs also found favour, as did Steve Carr's Paul Blart: Mall Cop, which laughed off scathing reviews to give Kevin James a January hit. Down the pecking order came Gary Winick's Bride Wars and David S. Goyer's The Unborn, while Marcus Nispel's Friday the 13th and Patrick Lussier's My Bloody Valentine (all 2009) proved that some classic horrors were best left unre-imagined.

Piled Higher and Deeper

Americans certainly aren't spoilt for choice when it comes to post-festive cinema. As the 2010 schedule suggests, however, quantity and quality are often poles apart. Titles like Michael Hoffman's The Last Station, Albert Hughes's The Book of Eli, Michael and Peter Spierig's Daybreakers, and Miguel Arteta's Youth in Revolt provided audiences with commendable entertainment. Respectively starring Ewen McGregor and Mel Gibson, Roman Polanski's The Ghost and Martin Campbell's Edge of Darkness occupied the middle ground. But Brian Levant's The Spy Next Door, Mark Steven Johnson's When in Rome, Scott Stewart's Legion, and Michael Lembeck's Tooth Fairy were slated in the press, even though they succeeded in avoiding commercial calamity.

The surprise inclusion among the 165 releases in Jan/Feb 2010 was Martin Scorsese's Shutter Island, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio and made over $294 at the box office. But films of this calibre are rare at this time of year and normal service was resumed in 2011, when dozens of undistinguished movies lined up alongside misjudgements like Michel Gondry's The Green Hornet and Dominic Sera's Season of the Witch. On the plus side, there was Peter Weir's Soviet survival saga, The Way Back, and the season's quirkiest curio, Kelly Asbury's animation, Gnomeo and Juliet, which wound up landing Elton John and Lady Gaga a Golden Globe nomination for 'Hello Hello'.

Similarly finding a silver lining was W.E., Madonna's critically and commercially underwhelming account of the 1936 Abdication Crisis, which managed to draw an Oscar nomination for its costumes. But there were plenty of other overlookable items on offer in the first part of 2012, with Asger Leth's Man on a Ledge, Julie Anne Robinson's One For the Money, William Brent Bell's The Devil Inside, Todd Graff's Joyful Noise, and Anthony Hemingway's Red Tails among the least distinguished. Even Steven Soderbergh came down with a bump with Haywire, although Liam Neeson scored another under-the-wire hit with Joe Carnahan's The Grey. But, when it came to epic badness, nothing could touch the multi-directored Movie 43 - which should be recommendation enough to make this Peter Farrelly-produced comic anthology your next must-rent title from Cinema Paradiso.

George Clooney would have shared their pain when The Monuments Men was consigned to a February launch spot in 2014. Few would have felt that Stuart Beattie's I, Frankenstein and José Padilha's RoboCop had been ill-served in being added to the list. But the odd hit kept coming, with Liam Neeson, being up to his old tricks in Jaume Collet-Serra's Non-Stop and the same duo would repeat the feat with The Commuter in 2018. However, the year's big winner was Phil Lord and Christopher Miller's The Lego Movie, which amassed $468 million on a $65 million budget.

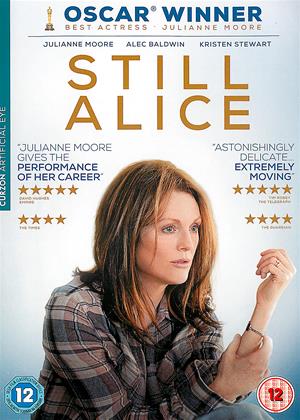

Liam Neeson (surely the Dump Month King) led the way in January 2015 with Olivier Megaton's Taken3, although he was closely followed by two more titles that deserved better release slots, Kevin Macdonald's Black Sea and Michael Mann's Blackhat. It's also easy to give the benefit of the doubt to Simon Helberg and Jocelyn Towne's romcom, We'll Never Have Paris. But the year's most misplaced film was Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland's Still Alice, which went on to earn Julianne Moore the Academy Award for Best Actress.

As January and February risked becoming saturated with imported genre films in 2016, three comedies stood out from the pack. To judge whether Joel and Ethan Coen's Hail, Caesar!, Ben Stiller's Zoolander 2 and Dan Mazer's Dirty Grandpa merited their dump month designation, rent them from Cinema Paradiso on high-quality DVD or Blu-ray. The jury might also still be out on Burt Steers's Pride and Prejudice and Zombies and Robert Eggers's The Witch. But Jared Cohn's Little Red Rotting Hood requires less deliberation.

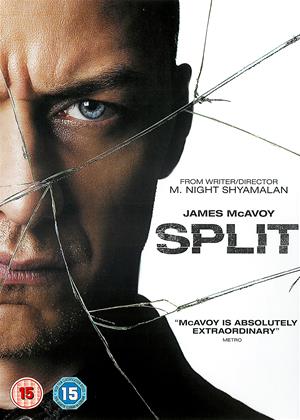

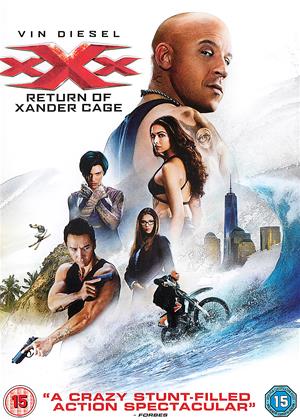

As we've seen, Get Out helped redefine the sleeper hit in 2017. Having enjoyed similar success with The Sixth Sense (1999). M. Night Shyamalan found himself in the dead zone with Split. A pair of blockbusting sequels, D.J. Caruso's xXx: Return of Xander Cage and Chad Stahelski's John Wick: Chapter 2 had to endure similar ignominy, along with Stacy Title's The Bye Bye Man. But Chris McKay's The Lego Batman Movie revelled in its uncool February release date while racking up $312 million worldwide.

Jennifer Lawrence found herself lining up against Adam Robitel's Insidious: The Last Key and Nicolai Fuglsig's 12 Strong when Francis Lawrence's Red Sparrow landed a February release spot. But so did Black Panther and it made $1.348 billion in becoming the first superhero movie to be nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards.

While Mike Mitchell's The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part lit up February 2019, the likes of Adam Robitel's Escape Room (2019), Darren Lynn Bousman's St Agatha and Neil Jordan's Greta skulked in the shadows (the latter in spite of the presence of Isabelle Huppert).

As the number of dumped titles increases, the greater the likelihood of forgettability. The decision to release Bad Boys For Life and Stephan Gaghan's Dolittle in January 2020 was tantamount to an admission of their inadequacies. The same could be said for Jeff Fowler's Sonic the Hedgehog, which emerged in February alongside Benh Zeitlin's Peter Pan retool, Wendy, and Nicolas Pesce's The Grudge, a remake of a remake that was produced by Sam Raimi.

Those films that did secure a release in early 2020 were soon shut out of cinemas by the pandemic and this situation continued into 2021. Consequently, contrasting items like Josh Greenbaum's Barb and Star Go to Vista del Mar, Shaka King's Judas and the Black Messiah, Lee Daniels's The United States vs Billie Holiday, and Kevin Lewis's Willy's Wonderland had to take their chances on whatever release format was available. They can now be seen in the comfort of your own home through Cinema Paradiso and long may they and future dump month releases continue to do so.